Arts & Culture

This Is What Activism Looks Like

We take a look at some of the key figures who are shaping both arts and activism in the city.

he marches and protests that brought in the new year were the first indicators that 2017 would be full of political discourse and civil unrest. And, as the arts have always mirrored the world’s events, artistic expression is at a vigorous high. That’s especially true for artists in Baltimore, who have borne witness to the death of Freddie Gray and the city’s accelerating murder rate. To usher in the arts season, we take a look at some of the key figures who are shaping both arts and activism in the city.

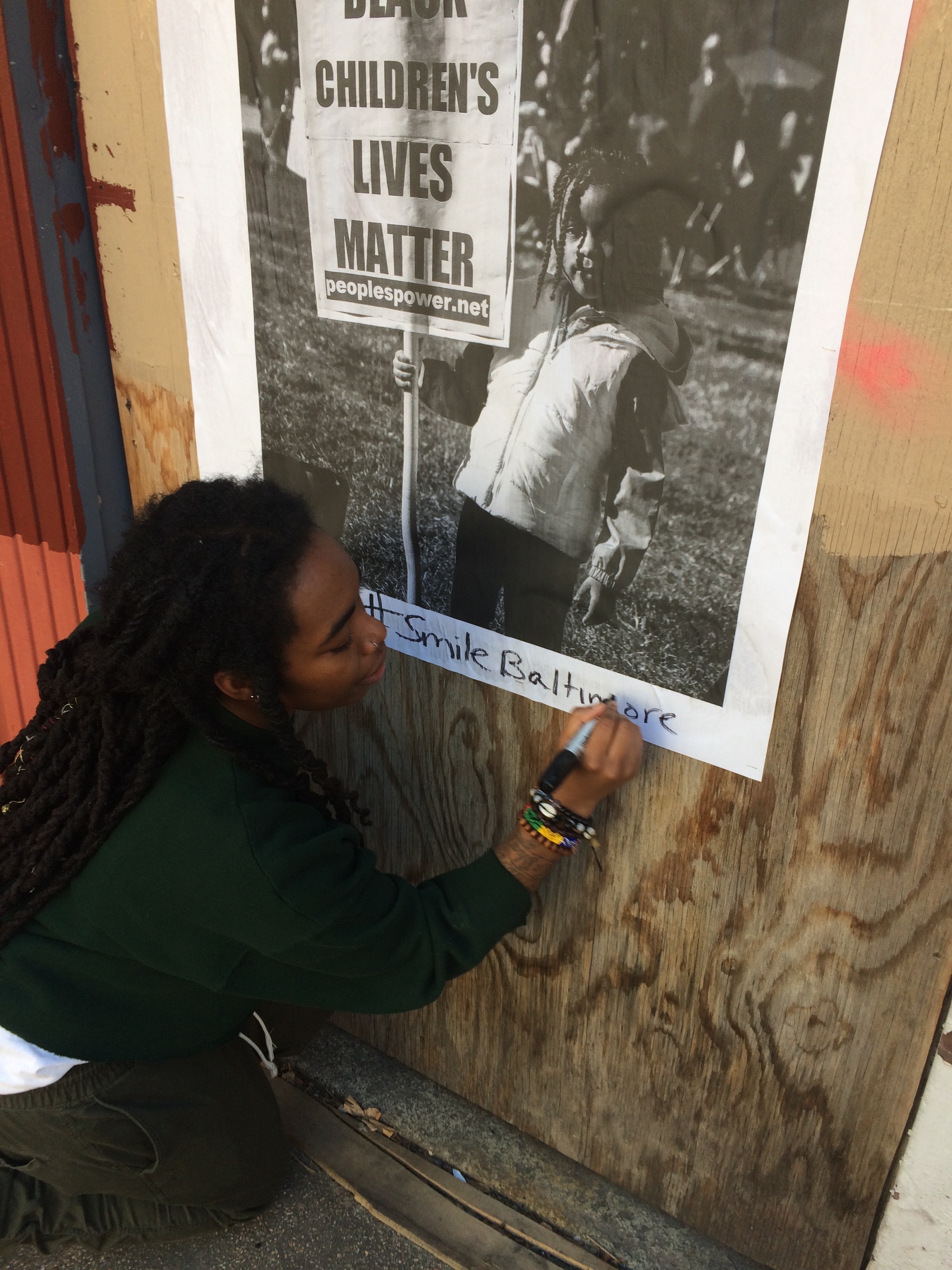

Shan Wallace chose a block on the edge of two worlds to display her work. To the north of the 400 block of Park Avenue you have what some would deem progress—luxury apartments on the rise and the bustling Mount Vernon Marketplace food hall. To the south, boarded up buildings and smashed windows stand out like busted teeth. “I’m tired of looking at this shit,” the photographer and activist says, eyeing spray paint-tagged boards screwed over a bay window, underneath a sunblasted sign that still reads “Jimmy’s Chinese Food.” “Why does this have to look like this? So I decided I’d put some art up.”

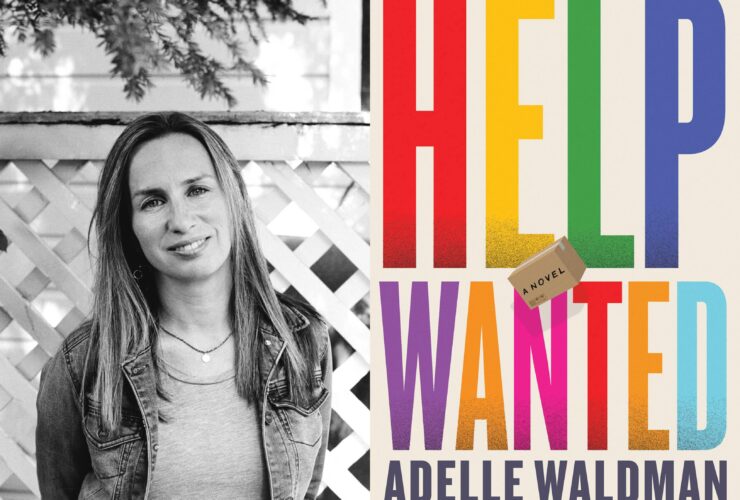

Wallace installing her work throughout the city.

Wallace, an East Baltimore native, has made a name for herself internationally by taking photographs that challenge the narrative of what it means to be black. There are depictions of a young father feeding a bottle to his tiny baby and protestors in powerful, open-mouthed stances at a march. It’s large prints of these photos, and others, that Wallace coats with wallpaper glue and affixes to vacant buildings on this spring day, the thud of a staple gun sealing her act of resistance. “I’m not even really supposed to be doing this, but who cares?” she says. “I just want people to embrace the community. And if you feel like you don’t love yourself, or like you hate your skin color, I want you to see my work and know people are standing with you.”

Wallace didn’t think twice about her action. It was innate—in her blood, so to speak. And that makes sense, because as an artist in Baltimore, she is following a lineage of artists who have similarly taken stands against social injustice, poverty, and civil inequalities in a city where these struggles are a part of daily life.

“We’re a highly challenged city,” says Baltimore artist and native Joyce Scott, one of last year’s recipients of a $625,000 MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant. “Our situation is just thrown in our face, and it feels like the whole world sees us as downtrodden and violent. And a very human response to this is an artistic one.”

Decades before the deaths of Michael Brown, Philando Castile, and Baltimore’s own Freddie Gray, Scott was referencing lynchings and rapes in her bold, luminous beadwork. You can trace the arc of Baltimore’s socially aware art from artists like Scott to the paintings of Amy Sherald, for example, who depicts her African-American subjects with power and depth, and Stephen Towns, whose work re-constructs the narrative surrounding historical figures such as slave rebellion leader Nat Turner.

“When you look at other cities, you can say ‘Oh, that’s the one artist or the one organization that has activism in their work,’” says George Ciscle, founder of the curatorial practice master’s program at the Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), as well as The Contemporary, Baltimore’s roving modern art museum. “But in Baltimore, so many of us are fighting this way—and it’s not just individual artists, it’s organizations as well. We really stand out in that regard.”

Installation process from The Artists For Truth inaugural benefit exhibition opening.

Nationally, and perhaps internationally, the 2016 presidential election brought artistic resistance to a new level. Artists Ai Weiwei and Kara Walker have consistently commented on political and social issues. Pulitzer Prize-winning author Toni Morrison wrote in response to George W. Bush’s 2004 election, “This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

If you scroll through the venerable online arts journal Hyperallergic, at least one story a day mentions art as a form of protest or exhibits with social justice-related themes. There are more public examples as well, like the “Fearless Girl” statue that now stares down New York’s Wall Street bull. (Interestingly, Baltimore’s New Arts Foundry had a hand in constructing her.) And when the Trump administration announced the possibility of drastic funding cuts for the National Endowment for the Arts, directors of major museums—the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, for example—spoke out in editorials.

The mural I Think That She Knows by Megan Lewis from The Artists For Truth inaugural benefit.

“Months into Donald Trump’s presidency, artists started organizing themselves and using their work as a filter or lens to address issues like immigration, equity, and privilege,” Ciscle says. “It’s not something that’s on the sidelines—it’s coming to the forefront in the national art scene.” He cites the Blue Black exhibit at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis, which ruminates on race in a city still grappling with the death of an unarmed black man, Michael Brown. “That might not have come together before 2016,” he says.

Though the national political scene has affected Baltimore, the death of Freddie Gray in 2015 had a larger resonance. Days after violence tore through the city, a mural depicting Gray went up at the West Baltimore spot where he was taken into custody. Artists organized vigils, exhibits, and concerts to give back to the community, but, just like everyone else, they’re still wrestling with its impact. Shows at Galerie Myrtis, MICA, and others tackled the black experience in America, but the response wasn’t limited to visual art. Writers D. Watkins and Kondwani Fidel, among others, have risen to national prominence by telling their own experiences of growing up in Baltimore’s poor, black neighborhoods. And in the classical music world, The Peabody Institute started offering a workshop called Art and Activism (led by Judah Adashi, who is featured on page 120) that allows music students to ponder their roles in a socially aware society.

“Freddie Gray has really made Baltimore look at issues of privilege, prejudice, equity, and talk about them,” Ciscle says. “I saw this with my grad students [at MICA], in regards to what they were talking about prior to Freddie Gray and since then, I’m not going to say it has put the black and white community together, but it has pointed out what the inequities are and said this is our priority as an arts community.” It was not a stretch, then, to imagine that Baltimore artists would respond to white nationalists marching on Charlottesville, Virginia, in August. Soon after, a Confederate monument in Bolton Hill was doused with red paint and activists placed Pablo Machioli’s sculpture of an African mother with her fist raised at the Wyman Park site of another such monument.

Though the national political scene has affected Baltimore, the death of Freddie Gray in 2015 had a larger resonance.

Machioli’s work remained as the Confederate monuments, as well as a statue of controversial Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in Mt. Vernon Place, were removed within a few days to much fanfare. The Walters Art Museum said in a statement that it was proud to be in a city where “monuments that glorified values we cannot condone have—literally—been taken down from their pedestals.” The Baltimore Museum of Art director Christopher Bedford—who called the removal “an opportunity to envision the art that best represents the aspirations and values of Baltimore”—is part of a panel that will decide what to do with the statues, and the spots that they leave vacant.

They could take a page from Wallace, whose work gets immediate interest on Park Avenue. A car beeps a series of friendly honks, a woman lingers by a photograph of a boy on a motorbike. “How ya’ll doing?” a passing man asks.

“What’s going on, man?” Wallace answers, signing her photos with a marker.

Then a man in a rumpled red coat with bloodshot eyes walks up the block. “Are these your photos?” he asks Wallace. When she says yes, he smiles and says, “These are very nice.”

After he leaves, Wallace is quiet. “I would rather do this than have an art show,” she says a moment later. “You don’t always have to give back by protesting. People have to be effective any way they can. This is my way.”

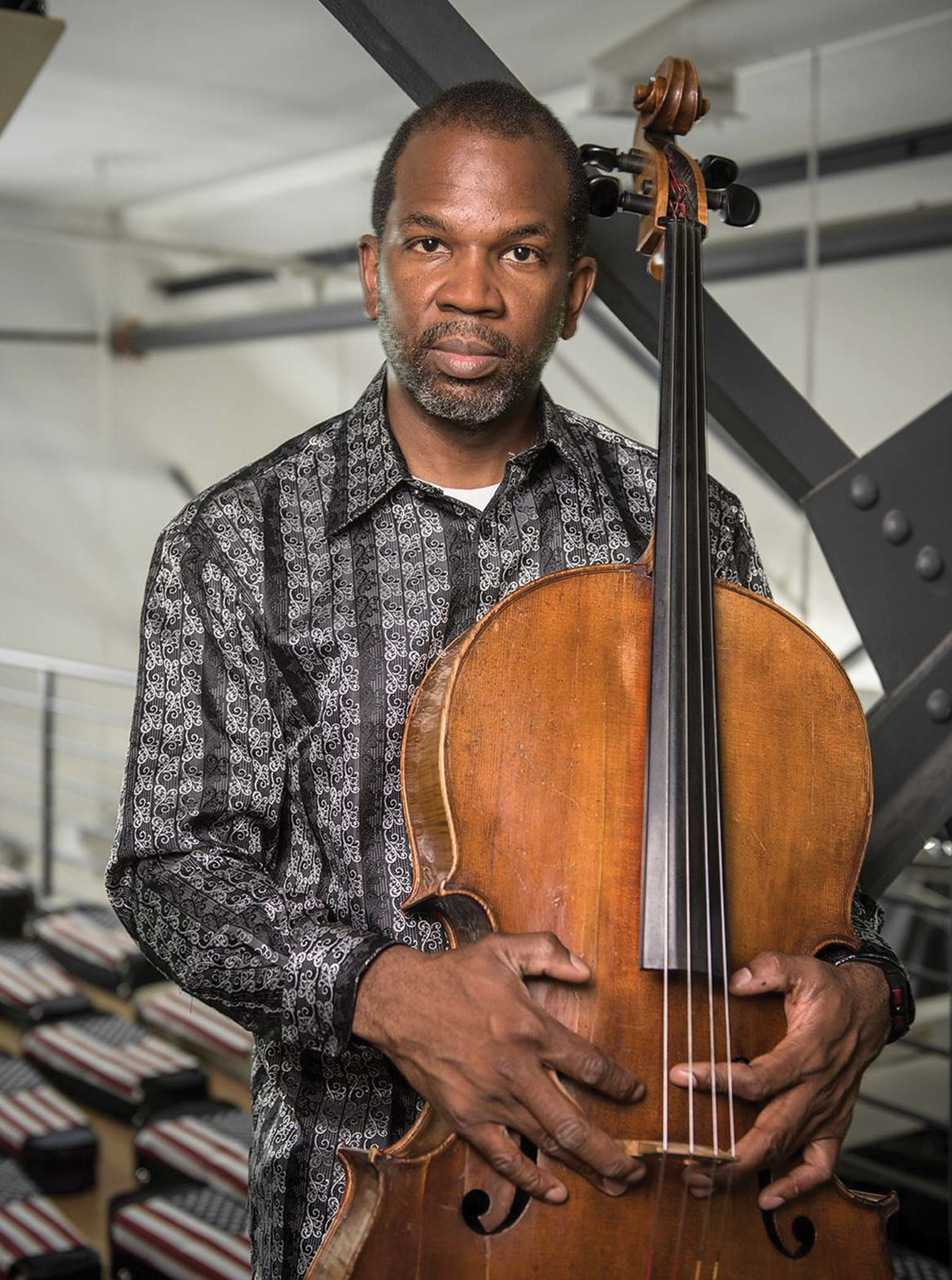

Visual Artist, composer, musician

Activist Work: A 2017 Guggenheim fellow and a winner of Baltimore’s Baker Artist Awards, Rucker examines human rights and communities, including the prison-industrial complex and how it relates to slavery. His exhibit Rewind, which addresses cultural and social issues relating to race, class, and power, is currently touring the country.

As told to Gabriella Souza: It was serendipitous because when my exhibit Rewind opened at the Creative Alliance in 2015, it was the same month that [the D. W. Griffith movie] The Birth of a Nation opened 100 years before, and that had set off a wave of white protectionism and fear in America. One of the reasons why my work is around this aspect of history is that history is repeating itself over and over again. My point was that hate groups still exist and they’re relevant and they’ve changed form. Several of the Ku Klux Klan robes I made for my show are camouflage, and I wanted to show that racism can have a stealth form, it have can have a protectionist or nationalist bent. But the thing is, you can’t always prove that it is what it is, you can’t always prove that you’re being treated differently, although you saw the person in front of you get called ‘sir’ and you aren’t getting called ‘sir’. It’s maddening, but the thing that I’ve realized is that people don’t realize what they’re doing. Even well-intended progressives, who think they’re being fair, are not acknowledging their surroundings. I love that there are a lot of white people who are putting out Black Lives Matter signs, but black neighbors matter—look at your neighborhood. Black jobs matter—look at your workplace. Who’s around you, who’s not around you? You’re in a city, Baltimore, that’s 64 percent black.

Paul Rucker’s Proliferation.

“My point was that hate groups still exist and they’re relevant and they’ve changed form.”

After the [2016 presidential] election, I realized that I didn’t need to take my show to New York or Los Angeles or Chicago—this show needed to be seen in smaller places. It’s going to Ferguson, then to York, Pennsylvania, then the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond. Ferguson couldn’t pay for it, so I sold a piece of mine to the University of Maryland, College Park, to fund my airfare and the airfare of the photographer documenting the show, as well as the cost of shipping, building, and presenting the show. I don’t sell a work to sell a work. Anything that I sell dealing with people’s deaths, I put the money back into a show or give it to another institution.

Being in Baltimore, it’s really important that we know more about slavery since this was a major slave port. We need to emphasize that slaves were not just big black men. They were pregnant women working in the fields, they were children, as soon as they could walk, who were made to shoo birds away from the field or participate in manual labor. This is important to me, but it should be important to America and American history as far as how we got here today, and who benefitted from these atrocities, and who’s benefitting now. We have to think about why we have what we have in place and how we got here—and if we don’t, it’s not going to be pretty. We’re wrestling with the soul of our city, and this city and this country are suffering.

Photographer, multimedia artist, and educator

Activist Work: Garcia’s 2015 exhibit Después de la Frontera (After the Border) at the Creative Alliance told the stories of undocumented youth and families who had fled their homes in Central America to come to Baltimore. Her work “Counterpunch” documents the fighting spirit of three Latina women who work at the facilities management department at the Maryland Institute College of Art. She is the editor and co-founder of Hyrsteria, a zine that highlights the social disparities that challenge our day-to-day lives.

As told to Gabriella Souza: The work I make is reflective of the communities I’m surrounded by or what they’re concerned about. Especially because I am Latina, immigration is something I’ve worked on for a couple of years, and is something that I care about. It’s even more intense since the presidential election, with deportations and raids, plus just the culture shock of being an immigrant—trying to find work, deal with the language barrier. I work a lot with narrative. Stories are something really innate to people. They’re from our ancestors, something we’re familiar with from our ancestors, and I think that stories are really powerful ways of teaching people. When someone tells you a story from beginning to end, your brain is imagining yourself in that story. That can create empathy to a certain degree. I make the work that I do using stories because it’s a powerful medium of teaching people. The work that I do, regardless of what it is, is about stories and sharing.

Tanya Garcia photography from #ShutItDown.

“oftentimes, we’re silenced for whatever differences we have, whether we’re a woman, a woman of color, an LGBTQ woman of color.”

I did a video in my exhibit Después de la Frontera of a woman from El Salvador telling her story of coming to the U.S. where I only showed her eyes. There are a few reasons why I did that. One is to keep some anonymity about who she is because she is undocumented. But her eyes really told a story, too—everyone’s do. The expressions you make, and your gestures, show in your eyes. I wanted the viewer to be confronted with her story and not look away. It’s simple in that there’s nothing else going on visually, it’s just her eyes, her oral history essentially, so you’re really focused on her and her story.

Storytelling like this is needed because, oftentimes, we’re silenced for whatever differences we have, whether we’re a woman, a woman of color, an LGBTQ woman of color. It’s combating this narrative that we aren’t important and we’re not human. The more you strip people away from their identity, their stories, their histories, their citizenship, their rights, the easier you can demonize them, call them a menace, say you should be scared of them. You’re feeding off people’s fear, and fear is really strong. Our government has done a really good job of connecting fear and safety to race, and it’s really important to contradict that narrative through personal stories of people who are responding to what they’re living through every day. Once that’s lost, it’s easy to just cast them off, ship them off as if they don’t exist, they don’t have relatives and families, they don’t have lives.

Performers during the Rise Bmore concert.

Composer, professor at the Peabody Institute

Activist Work: Adashi is the founder and director of Rise Bmore, a multifaceted concert held each year on the anniversary of Freddie Gray’s death, and the founder and artistic director of the Evolution Contemporary Music Series. His choral work “Rise” traces America’s civil rights struggles from Selma to Ferguson and beyond.

As told to Gabriella Souza: I think a lot about my own upbringing and how it relates to the things that I do now. My mom is from Romania and my dad is from Israel. I was a sheltered only child, who was taught to do well, taught to not rock the boat. I’ve definitely become more attuned to the fact that I’m first-generation American. I used to not care about it at all, because when you’re a kid, all you want is to be like everyone else, and your immigrant parents are just a hindrance to that. Then you learn how meaningful it is to be other. One of the things I’ve noticed is that what a white person goes through is relatively easy. But people want to decry calling out racism more than they want to decry racism. Apparently the word “racism” is nastier to people than the thing itself. Just like there are people for whom the Baltimore Uprising in 2015 will forever be violent when I always hold fast to the idea that the single most violent act of the Uprising was the murder of Freddie Gray.

“Music is a good figurative space in which to engage with these things. ”

That, to me, is what most of my music is about. Music is a good figurative space in which to engage with these things. There are many schools of thought about what it means to write activist music. A composer friend of mine [David T. Little] makes a distinction between revolutionary music and critical music. Revolutionary music is essentially propaganda; critical music is a sense of bearing witness to things so that they’re not forgotten, so that they don’t become casualties of cultural amnesia—you are not offering the truth or the conclusion. I think Freddie Gray is a pretty distant memory for some people, and that’s unbelievable. I do think that’s not as common with cultural traumas that affect white people equally, like 9/11. He had no intention of being the symbol that he has become, and he deserves to be alive. But he did touch something in a lot of people here, and that’s powerful. That’s what I see in Baltimore. So much art seems to come from that place—that deep love of this city, and a pretty clear-eyed awareness that we are one of the ground zeros for what it looks like when a city was conceived as hyper-segregated and people here still live that truth in many ways. Art can connect artists across different genres, races, ages, genders, and identities of all kinds, and it also invites people into what that creates. I think it has potential to heal, to transform, to make people sit with discomfort. That’s what I’m trying to do with Rise Bmore, to form community around this remembrance.

Poet, organizer

Activist Work: Agostini is a founding member of the Rooted Collective, which is a gathering of black LGBTQ people in Baltimore that creates events featuring music, art, and conversation centered around healing. She is a part of the Black Ladies Brunch Collective, a group of poets that just published its first book, Not Without Our Laughter. She serves as the chief operating officer of FORCE: Upsetting Rape Culture, which works to support survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault and transform cultural attitudes to prevent rape and abuse.

As told to Gabriella Souza: At a very young age, I survived sexual abuse. I didn’t have the words for it, I didn’t know how to name it. I grew up in a family where you trusted adults, you trusted the people around you, and when I started telling people, it was hard for them to comprehend what to say to me or what to do. I just thought, ‘okay, this is my fault, this is something that is my burden, I failed the people around me.’ I took that with me, I carried that as my shame for a very long time. When I was about six, my grandmother taught me how to write, and that was the first place where I could go to where no one was telling me what I could and could not say. I couldn’t talk about being sexually abused, I couldn’t talk about the violence I was seeing in my home, I couldn’t talk about the pain I was feeling in my body, but I could write these poems. I don’t think I could articulate it at that time, but that became a point of resistance.

Saida Agostini shares her piece, Bresha Meadows Speaks On Divinity.

“it’s not just about what it is that we’re fighting against, but it’s actually about what we’re fighting for.”

I really carried that with me, and I was really fortunate that I had this beautiful collective of black writers who saw my work and said this is what you need to be doing. I think what we often forget about resistance work is that it’s not just about what it is that we’re fighting against, but it’s actually about what we’re fighting for. The most radical art helps us think about different ways to think, different ways to feel, and the world that we want. For me, I want a world that is safe, and a world where I don’t have to say black lives matter, where I don’t have to say that my life as a black queer woman or the lives of black trans women matter, because it’s just as accepted and as natural as breathing.

Everybody has their own path around artistry and resistance, and for me, storytelling and talking about my own experience and what has happened within my body has become so important for me. We’re taught that there’s this ethic of responsibility politics and if you’re black you have to present this perfect image. I did all of the right things, went to the right universities, got the right grades, and I wasn’t happy. I even tried not to be a poet for a really long time because I felt like I didn’t fit into the box of what my parents and my family would want. And I kind of kept going back to the thing where what makes me most joyful, and when I’ve seen my family and my people be most joyful, is when we’re sharing these stories. So that means that truth-telling is the best thing that I can do, when I’m standing in witness of what I know.

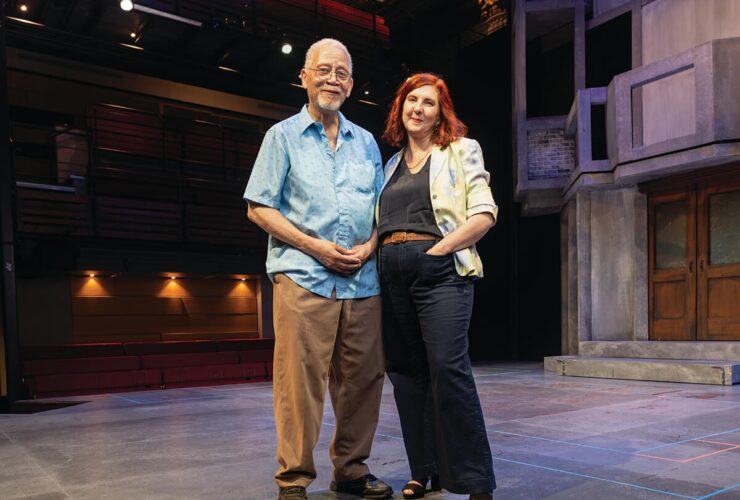

Members: Melissa Webb (MW), Amy Eva Raehse (AER), Maggie Villegas [MV], Ryan Hoover [RH], Rob Ferrell, Lillian Hoover, Bart O’Reilly, Emily Jane Soontornsaratool

Activist Work: This collective of artists, professors, and curators organized its first benefit exhibition in June, showing more than 250 artworks by 150 local and national artists. Through the sale of those artworks, it raised $16,000 for The Center for Media Justice, the Baltimore Action Legal Team, the Enoch Pratt Free Library, and The News Literacy Project.

As told to Gabriella Souza: MW: Soon after the 2016 presidential election, Lillian [Hoover] posted an inquiry on social media asking if anyone wanted to put on a benefit exhibition. There was just this feeling of helplessness, that things had spiraled out of our control. All who responded were looking for a way to contribute—to utilize our skills as artists and organizers to unify the community around collective concerns, and to find a way to raise money to aid organizations that have long been focused on issues we care deeply about. After much discussion surrounding civil rights, police brutality, and climate change, among others, we moved toward the issue of truth, and the consistent lack thereof. The deliberate misinformation and manipulation of facts in media and political discourse encapsulated so many of the concerns we had. It turned out to be timely, right before “fake news” became the news.

AER: The chaos leading up to—and the repercussion of—the election was sobering, just as the proliferation of fabricated information was overwhelming. The safety of our citizens felt tenuous. We were still trying to rise up, as a unified city, from the impact and implication of Freddie Gray’s death, and we suddenly had an unstable man—who openly expressed hateful, misogynistic, racist, homophobic, anti-immigrant, anti-culture views—leading our country. Baltimore needed a counterpoint to the anger—something restorative while remaining an act of resistance. We wanted to do something to send a message, and we wanted to help artists find their voices because artistic voice has been a potent looking glass and change maker throughout history.

The Artists For Truth inaugural benefit exhibition opening.

MV: There’s a sense of social responsibility here in amplifying the work of other activists, in educating, that I just hadn’t seen before moving to Baltimore. It’s central to how artists think here. People here don’t wait for the city or institutions to solve problems for them. They are focused on figuring out what they can do themselves. I think they recognize that it’s the best way to get shit done. And that might be frustrating, but it’s also empowering.

RH: Some artists in Baltimore address political issues as the subject of their work, some engage in political action through their work, and other artists are politically active outside of their art practice. I think this ethos comes from the city in general. We have problems, but they often bring people together to work on solutions and make a real difference. There is a lot of work to do in this regard, but there is a tremendous amount of value in bringing people together to share knowledge, perspectives, and resources. I value not just the activist spirit of the arts community, but the way the activist community welcomes and incorporates the arts into their practices. I hope these lines continue to blur even further as more relationships are built.

“We wanted to do something to send a message.”