“I wander around people’s attics, out in fields, in cellars…” —Andrew Wyeth 1917-2009

As the great Wyeth did with his easel in the Pennsylvania town of Chadds Ford, local landscape artist Lissa Abrams does in her hometown of Baltimore.

Abrams is one of those people—there’s at least one in every family—who drives through the old and often greatly changed neighborhoods where her ancestors once broke bread, helped a friend with a problem, raised kids, and told stories.

Sometimes it’s a sad stroll—the houses boarded up or gone completely—but other journeys bring a smile through the mist of years gone by.

“My parents used to drive around, too,” says Abrams, whose mother Rosalie Silber Abrams (1916-2009), grew up in a successful Baltimore bakery family and became the first female majority leader of the Maryland State Senate.

Abrams’ late father, William, grew up on a block of Linden Avenue (now torn down) near Druid Hill Park before the family moved to Dorchester Road in Forest Park. His parents belonged to the Bais Hamedrash Hagodol Congregation at Baltimore and Chester Streets in East Baltimore, a synagogue which is now also gone.

These memories were going through Abrams’ mind last year when she attended a funeral at Wayland Baptist church on Garrison Boulevard in Forest Park. Noticing the Stars of David on the building, she remembered it as the original Beth Tfiloh synagogue, which was built in 1927.

She decided that such places—of which there are many in Baltimore, where the Jewish community goes back to the early-and-mid-19th century—needed to be preserved in oil even if the brick and mortar had fallen.

And now, they are. Some 55 paintings of eight synagogues by about a dozen-and-a-half artists, both Jewish and Gentile, are now on view in an exhibit at the Hoffberger Gallery of the Baltimore Hebrew Congregation on Park Heights Avenue. A reception for the exhibit—in which synagogues both defunct and still in operation are depicted—will be held on Sunday, September 15th at Baltimore Hebrew, and the paintings will be on display through October 28.

“I like painting moments in time,” says Abrams, treasurer of the Mid-Atlantic Plein Air Painters Association, several members of which are in the exhibit. “I love painting things that are old, that might be gone in a couple of years.”

Abrams has learned that, in Baltimore—where history long precedes the founding of the nation—”now you see it, now you don’t” can happen to just about anything at any time.

“A lot of these are big, beautiful buildings that take a lot of maintenance,” she says. “I’m sure they’ll be around for a while, but eventually…you never know.”

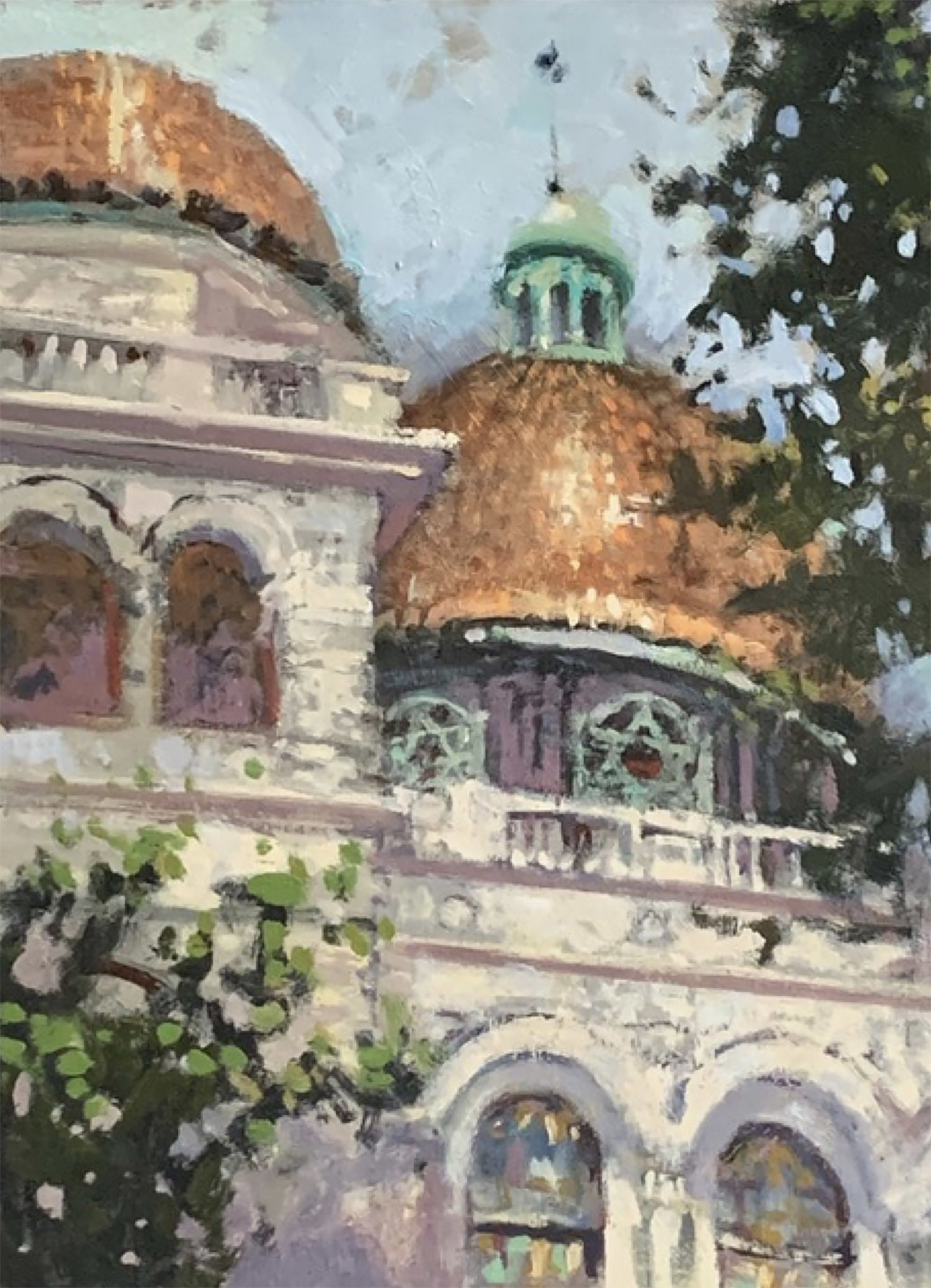

“Oheb Shalom, Study of Form and Faith” —Stewart White

“Gone” Ahavas Achim—Lissa Abrams

The synagogues—or shuls—portrayed in the exhibit include B’nai Israel on Lloyd Street near Corned Beef Row, still vibrant in the one-time epicenter of Jewish Baltimore; Shaarei Tfiloh, also in operation, in Druid Hill Park (where the Jewish community migrated after first settling in East Baltimore); and the former Eutaw Place Temple of the Oheb Shalom congregation in Bolton Hill, designed by Joseph Evans Sperry, best known as the architect of the Bromo Seltzer Tower.

Another painting of note is a sad and beautiful corner building (boarded up and scarred) of pale orange brick—once home to Congregation Ahava Achim at 427 Pulaski Street—in southwest Baltimore, an area known during the Great Depression as “Little Jerusalem.”

“I’m honest [in depicting] all the work I do, but when you’re painting a religious building there’s an extra feeling of, ‘I better get this right,’” says Crystal Moll, perhaps Baltimore’s best known plein air artist who contributed a canvas of the old Eutaw Place Temple, modeled after the Great Synagogue of Florence, Italy and now a Masonic Lodge.

“I’ve always wanted to paint that building,” says Moll, who did a 16 inch-by-16 inch detail of the grand building’s domes and also has a painting of Shaarei Tfiloh in the show. Each visit to Eutaw Place, she said, took a few hours and she set up her easel there about six times before completing the work.

“You always have great conversations when you’re sitting on the sidewalk painting,” Moll says. “People come up and say that they’re an artist too, pull out their phone and show you pictures of their work.”

Which is all well and good. You can’t really haul around framed canvases all the time to share your art with friends and strangers. But long after digital images have been deleted or lost in some cyber crash, oil on canvas—like the faith represented in the “Baltimore’s Bygone Synagogues” show will endure.

“It’s about making sure all the colors work together,” says Abrams. “I’m not too mystical—with me, what you see is pretty much what you get. It’s all about capturing the light…”

Along with a couple of centuries of faith, migration, and history in the Queen City of the Patapsco River.