Arts & Culture

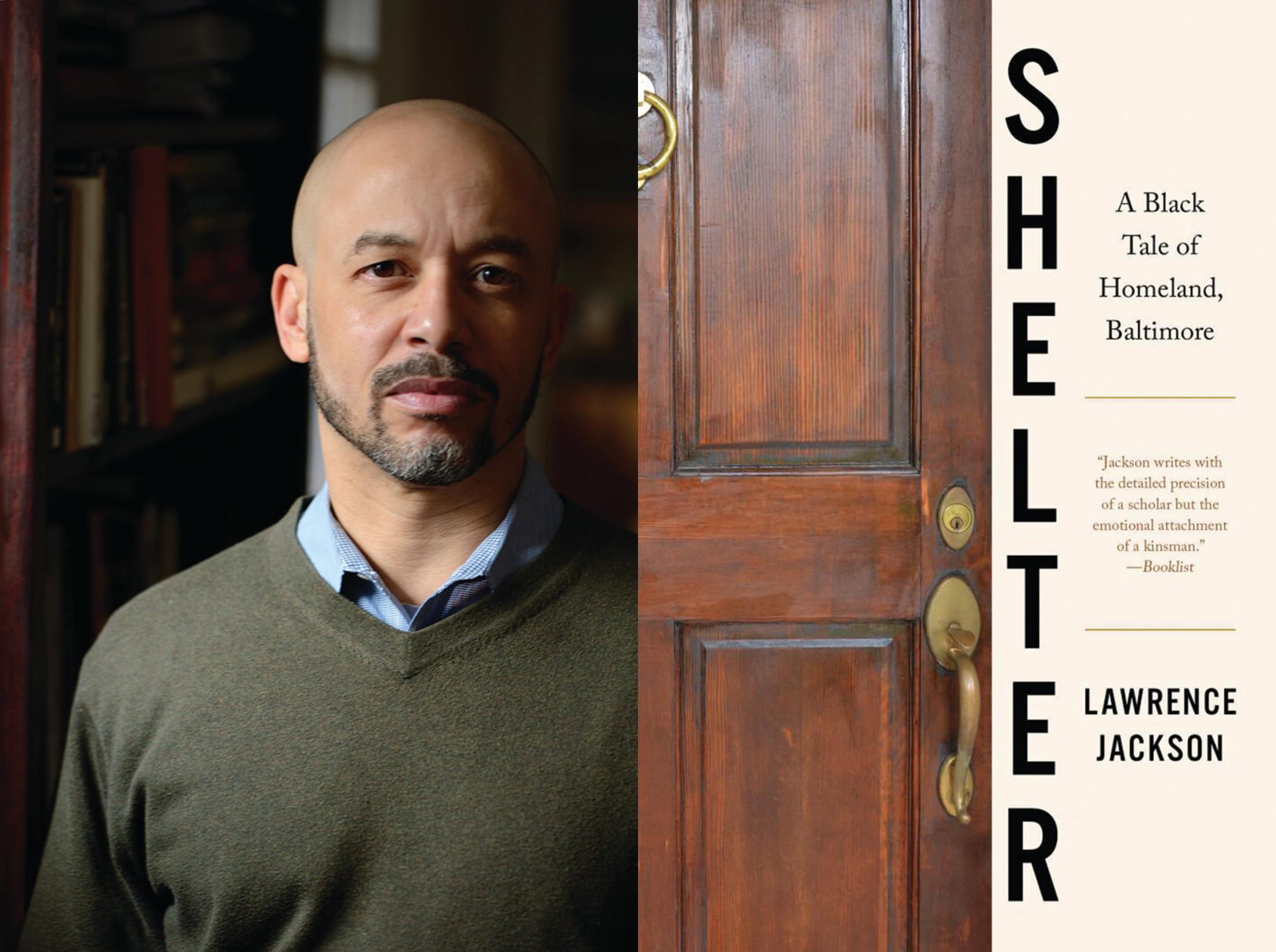

Lawrence Jackson’s Memoir Explores a Circuitous Journey from Park Heights to Homeland

The distance between the two neighborhoods is only 4.5 miles, but it’s as long and fraught an odyssey as any in this country.

Author Lawrence Jackson, whose works include the award-winning biography of Black crime novelist Chester B. Himes, returned to Baltimore from Atlanta’s Emory University in 2016. Accepting a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and History position at Johns Hopkins University, Jackson launched the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts as a means of connecting the elite institution to the West Baltimore community where he was raised and still attends Sunday church.

Due to be published next month, Shelter: A Black Tale of Homeland, Baltimore explores his circuitous journey from Park Heights to the wealthy enclave of Homeland, where he bought a house upon his return to the city. The distance between the two neighborhoods is only 4.5 miles, but it’s as long and fraught an odyssey as any in this country, and Jackson meticulously chronicles all the surreal and difficult complications of that journey. The memoir is both a personal and wide-ranging examination of history, place, and race, and a work of literature like nothing else set in present-day Baltimore.

You obviously possess a deep curiosity about your environs, both immediate, in terms of your home and neighborhood, and regarding the broader city. Is this instinct intrinsic? Acquired? |

As a child, play began in the alley, filled marvelously with potholes, pebbles, and rocks, and recreation begat a network of hoppable fences and paths and cuts and chutes that had to be learned and reconnoitered. What began off of Bareva and Belle Avenue, and then over to Towanda, eventually produced a pragmatic curiosity about the other parts of the city, especially its bus routes and the secondary streets where safe and flairful bicycle riding was plausible.

Some of the terrain you cover reminds me of Edward P. Jones, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington, D.C., author of the short story fiction collection, Lost in the City, who has praised Shelter.

I am lucky to have Edward P. Jones as an old friend. His writing, which inspires me greatly, and his career as a writer remind me that things are not exactly what they seem. We have to rely upon what Stevie Wonder, a prophetic lyricist for my father and older sister, used to call “Inner Vision.” Until I read Lost in the City, I had not read fiction about people from the urban social world that I had known as a child and young adult.

One story you bring to light is that of a largely unknown Baltimorean named David Perine, a Lost Cause enthusiast and likely one-time enslaver who bought and eventually sold the property where you reside to the Roland Park Company.

I love the Maryland Center for History and Culture, where Perine’s family’s papers are kept. I was quite surprised to find out so many intimate details about the wealthy scoundrels Perine and his friend Roger Taney. But a part of me melted when I thought of Homeland as a gigantic orchard. I spent a little time in Benitachell, Spain, where the Moors introduced terraced agricultural practices, and the harvests there were magical.

You discuss the perceived need and decision of Johns Hopkins to launch its own police force, which feels emblematic of many of the issues particular to Baltimore that you explore.

Yes. It’s a predicament, a conundrum, a paradox. I am not an economist or a government official, or even a policy wonk. Our city operates from a budget of about $2 billion and devotes half of that to public safety. This ratio away from public education shifted fully in the 1990s, so the claim that more public safety is a finger in the dyke keeping full-blown mayhem at bay seems ridiculous to me. We have lived in mayhem for generations. You want to take the edge off of the streets? I would say graduate more young men from high school.

Riding MTA city buses to school always leaves an indelible mark on people who grew up here. Reading this, I wondered if your own observational and writerly curiosity began there?

The busses are a rite of passage, but also a laboratory for democracy. On the bus I was always conscious of my vulnerability, but I was also keen to take advantage of opportunities for independent mobility and thought, and chances to stir and harness my imagination and test the power of my own will. Those are probably key instruments in any writer’s tool kit.