Arts & Culture

Photography by Schaun Champion, Ryan Chance, Justin Tsucalas, Shan Wallace, and Isaiah Winters

WHEN THE CORONAVIRUS arrived in Baltimore this March, some of the first people to feel the effects of the new global pandemic were artists. Concerts and exhibits were quickly postponed, then canceled, with museums and music venues imposing social-distancing restrictions before ultimately closing their doors. The halls grew quiet at The Walters. The curtains hung heavy at Center Stage. The seats sat empty at the Meyerhoff. Even Station North, usually bustling with nightlife between The Crown and Motor House, had gone dark.

Overnight, musicians, painters, actors, photographers, and more watched their livelihoods come to a screeching halt. Resources and relief funds attempted to ease the economic pain, but by early May, nearly two-thirds of the nation’s artists were unemployed, according to the nonprofit Americans for the Arts, and with no end in sight.

But art, at its essence, is a response to the world around it, with some of history’s greatest masterpieces borne out of times of crisis. (Shakespeare apparently wrote King Lear during the bubonic plague.) And so artists here did what they do best, honing their various mediums and the city’s DIY spirit to help us make sense of it all. Even as crowds could no longer fill galleries and theaters, they found fresh ways to create, turning to the internet, where they would bring art to the quarantine comforts of audience’s own homes, and eventually the great outdoors.

The Baltimore Symphony Orchestra launched Offstage, where violinists and cellists performed livestream recitals from their living rooms. The Baltimore Museum of Art debuted its BMA Salon and Screening programs, where local gallerists presented exhibitions on virtual walls. The Creative Alliance offered DJ dance parties on Zoom, while the Sondheim Artscape Prize was announced via YouTube, and the Parkway Theatre held its annual Maryland Film Festival online. All the while, photographers took self-portraits, writers kept quarantine diaries, and creatives of all kinds crafted “isolation creations,” from floral designs to dress-up recreations of famous fine art on Instagram.

Then not long after the first lockdowns were lifted, another crisis emerged, as George Floyd, a Black man in Minneapolis, was killed under the knee of a white police officer and the United States began to wrestle with its own epidemic of racial injustice. Even in the midst of COVID-19, the newly invigorated Black Lives Matter movement inspired artists to both document and delve into our national strife—picking up cameras, grabbing paint brushes, firing up presses to print free protest signs (we see you, Baltimore Print Studios and Globe at MICA). By the end of summer, Baltimore’s artists of color had once again made national waves, with works by photographer Devin Allen—a powerful image from a march for the Black trans community—and painter Amy Sherald—a poignant portrait of Breonna Taylor—landing on the covers of Time and Vanity Fair magazines, respectively.

As of press time, the rest of 2020 remains unpredictable, leaving the future of the arts in limbo. There is still no vaccine, even as Governor Hogan has announced stage three of the state’s recovery plan, including the reopening of live entertainment venues at half capacity, and museums have welcomed the public back inside, while the country’s incredibly tense racial and political division only intensifies on the eve of the November election. But there is one certainty, as demonstrated across the city this year, throughout and despite it all: Artists will carry on, one way or another. Here are some of their stories.

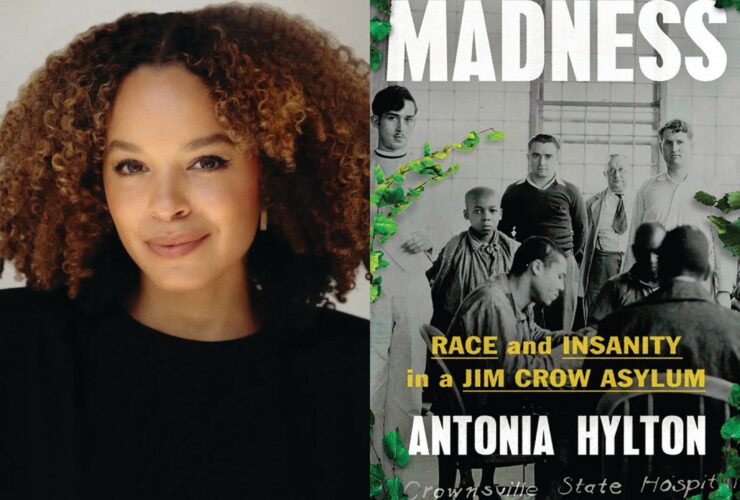

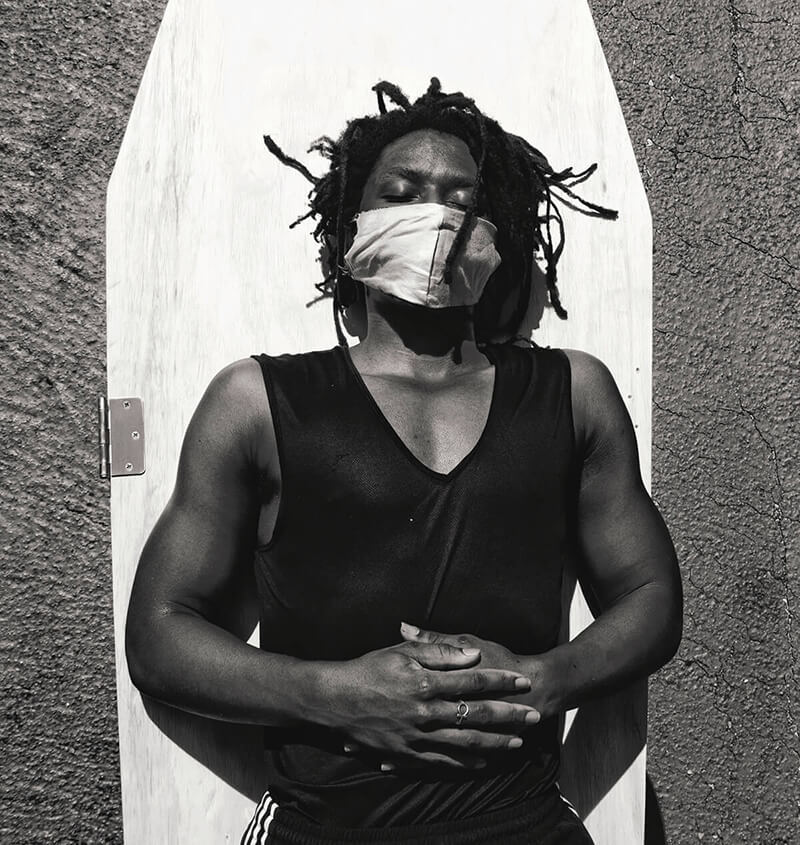

IN A FLASH

A street photographer documents a summer of protest.

Matthew Pasley, right. Photography by Shan Wallace. Pasley's images from recent protests in baltimore, left.

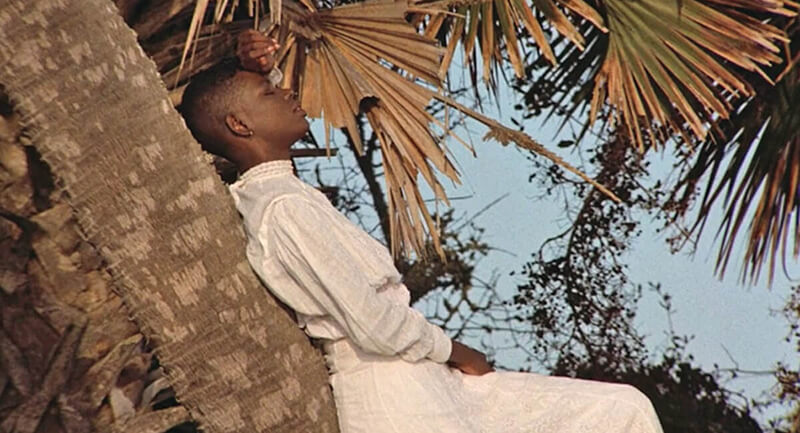

THE FIRST PROTEST Matthew Pasley attended as a photographer was during the 2015 Baltimore Uprising following the death of Freddie Gray. As a Black man, he had experienced his fair share of negative encounters with the police. Growing up in South Carolina before moving to Baltimore in 2002, he saw friends and family members assaulted and wrongfully arrested.

“It was a form of self-expression,” says Pasley, who has largely worked in event photography over the years. “A friend loaned me a camera, and what better time? It was an exciting, eye-opening, alarming experience. I’d been to protests before but to actually be in the midst of documenting it was a new feeling that sparked a desire to continue to do so.”

After the death of George Floyd this May, he took to the streets again, this time with his own Canon T5i, as well as his iPhone. With comfortable shoes and enough water to stay hydrated in the summer heat, he wove through the crowds to capture multiple protests that popped up across the city in the next few weeks, including the youth-led and women’s marches, as well as rallies outside of City Hall. His bold, black-and-white photographs, as well as video footage, depict masked faces, hand-drawn signs, and candid moments of camaraderie.

“I’m trying to find some light in all of this darkness,” says Pasley, noting the importance of having local photographers on the ground to convey the narrative. “We want to capture those strong, sometimes hard-to-bear moments, but even with all of the pain we’re out here to recognize, I want people to know there is also joy.”

CITY MUSIC

A rising rapper turns the street corner into a stage.

zadia, center, with her band at druid hill park. Photography by Ryan Chance.

THIS JUNE, after a nearly two-month stay-at-home order, the streets of Baltimore once again filled with the joyous sounds of city life, but this time through the clashing drums, rippling trumpet, and raspy, soulful vocals of Zadia, aka Cheyanne Givens, who just released her debut album.

“When I finally dropped music, I couldn’t wait to tour different venues,” says Givens, who recorded Vacants during quarantine. “Then the pandemic hit and it was like, ‘What are we going to do now? How can I be innovative and still bring the same feeling in a way that respects the restrictions?’”

Teaming up with the Creative Alliance’s Sidewalk Serenades, the young rapper embarked on a series of pop-up concerts across her native West Baltimore, toting mics, amps, and drum kits across six stops for an impromptu, open-air music festival. They appeared on curbs and at corner stores, in traffic medians and down alleyways, in front of the Arch Social Club in Penn North, and in the middle of the basketball court at Druid Hill Park. Her band, which includes trumpeter Brandon Woody, drummer Josh Stokes, and keyboardist Troy Long, plus backup vocalists like Al Rogers Jr. and Bobbi Rush, used three cars and a Lyft to move between each location, even performing an extended set in the rain.

“This is the future, and the past,” says Givens, who also did a half-dozen stops in East Baltimore three weeks later. “Black people have been performing in the streets for a long time. There is a freedom to it. You’re not restricted to rules of venues, and you never know who is going to walk up and experience your music, who needs to experience your music. It felt like we were doing what needed to be done for the community.”

For that, Givens is planning a national tour for Vacants, which is inspired by her gospel music upbringing and the jazz of Pennsylvania Avenue, speaking to the city’s thousands of vacant homes. “Music will always be a connecting art form,” she says. “My message with these shows is that we’re all in this together.”

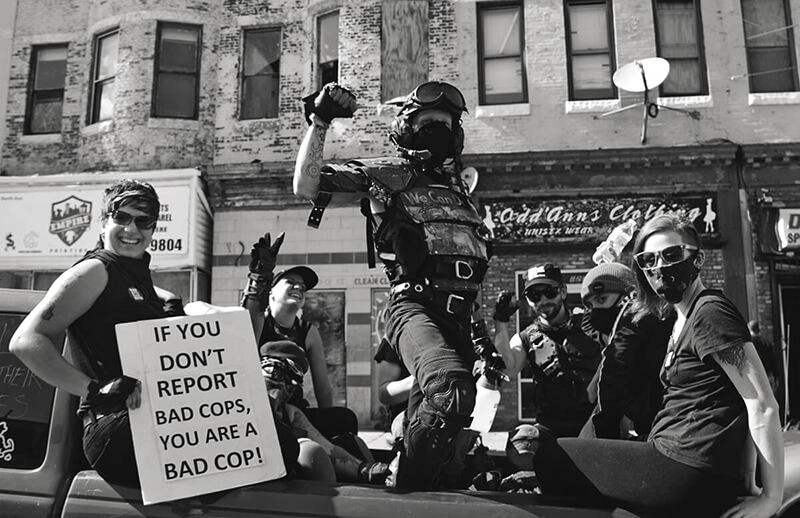

WINDOW TO THE WORLD

Local curators showcase the power of public art.

The People United at Current Space. PHOTOGRAPHY BY ISAIAH WINTERS.

ON A HOT SUMMER NIGHT in late July, a group of people gathered on Howard Street, looking into the wide windows of the Current Space gallery at stirring black-and-white photographs while five old televisions buzzed with scenes of Baltimore. For many, it was their first exhibition since the coronavirus relegated artists to cyberspace.

“It’s one thing to see art on your phone or a computer,” says Casey McKeel, who co-curated The People United with Teri Henderson, coordinator of nomadic arts platform WDLY and BmoreArt’s Connect + Collect. “We had so many people say it was just so nice to see it in person again.”

Like many curators, Henderson and McKeel, who is also an organizer of photography collective Rebel Lens, had been derailed by COVID-19, originally planning an in-person exhibit. But instead of pivoting to virtual programming, they brought their experience to the city streets.

The show’s title was a nod to a popular protest chant—“the people united will not be divided”—centering seven Black photographers, including Rob Ferrell, Shae McCoy, and Philip Muriel, with images that spoke to systemic racism and police corruption, all taken during recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations in Baltimore and now for sale through the gallery. A video installation in collaboration with I Got a Monster authors Baynard Woods and Brandon Soderberg also depicted imagery from their upcoming documentary on the police department’s Gun Trace Task Force.

“We wanted to present a beautiful, compelling, provocative response to the movement that got people talking in a positive way,” says Henderson. “These images really serve to document history, and they’re captured by Black artists through their own lens.”

Through late August, the window exhibit was up for local residents, Light Rail commuters, and all walks of passersby to see, with its social distancing-friendly display turning the main thoroughfare into an unexpected art gallery.

“The power of public art is accessibility,” says Henderson, who envisions more exhibits like it in the future, as seen in recent window shows at the Waller Gallery and Impact Hub. “Not everyone feels welcome in museums and galleries—the beauty of public art is that it truly is for everyone.”

COVER GIRL

A vintage maven makes pandemic fashion.

A GET SHREDDED MASK. COURTESY OF SARA AUTREY

WHEN SARA AUTREY purchased her first sewing machine two years ago, she was just expecting to use the equipment to mend the secondhand threads sold at her Get Shredded Vintage shop, now located in Remington. But this April, Autrey, pictured, who is also a musician, found herself in her basement, trying to figure out how to make face masks for her family in the wake of a global pandemic.

“The first one I made was with chambray, I added a ridiculous amount of fringe, jokingly put it on Instagram, and the feedback was dozens of people like, ‘Do it!’” she says with a laugh. “We use fashion to express ourselves and how we’re feeling. In one of the crappiest phases of most of our lives, making something that’s functional but also fun feels good to be able to do. Having my hands moving and my mind occupied with something constructive was so helpful for me.”

With retail impacted by COVID-19’s subsequent economic crisis, mask-making became an outlet for Autrey, who has made nearly a thousand face coverings out of vintage fabric thus far and plans on designing more playful sets such as those with matching dog bandanas.

“I want to turn masks into something cheerful, instead of a cold medical reality,” she says. “As long as people keep needing them, I’ll keep making them.”

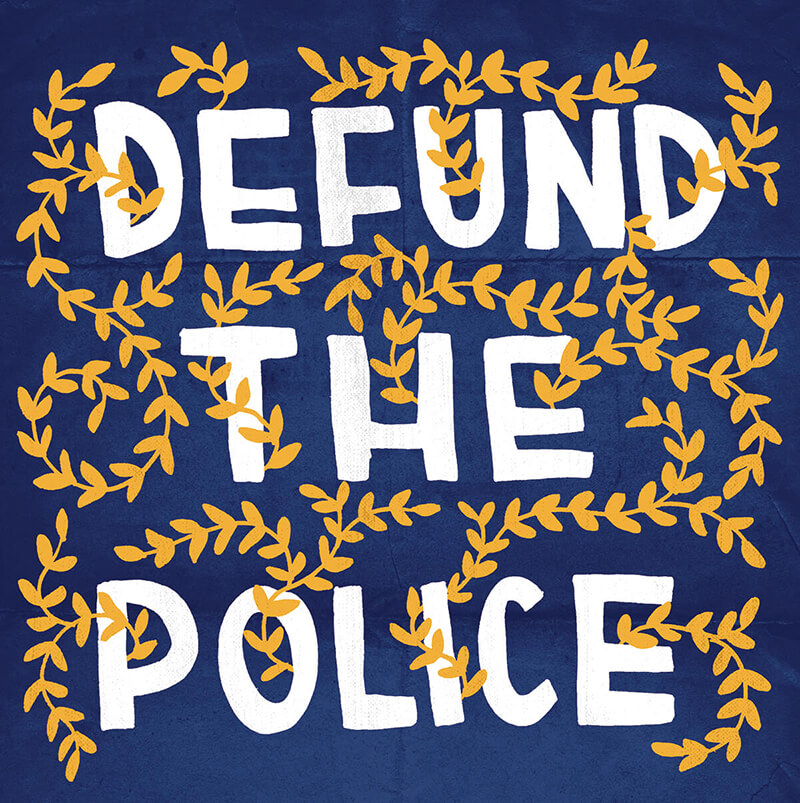

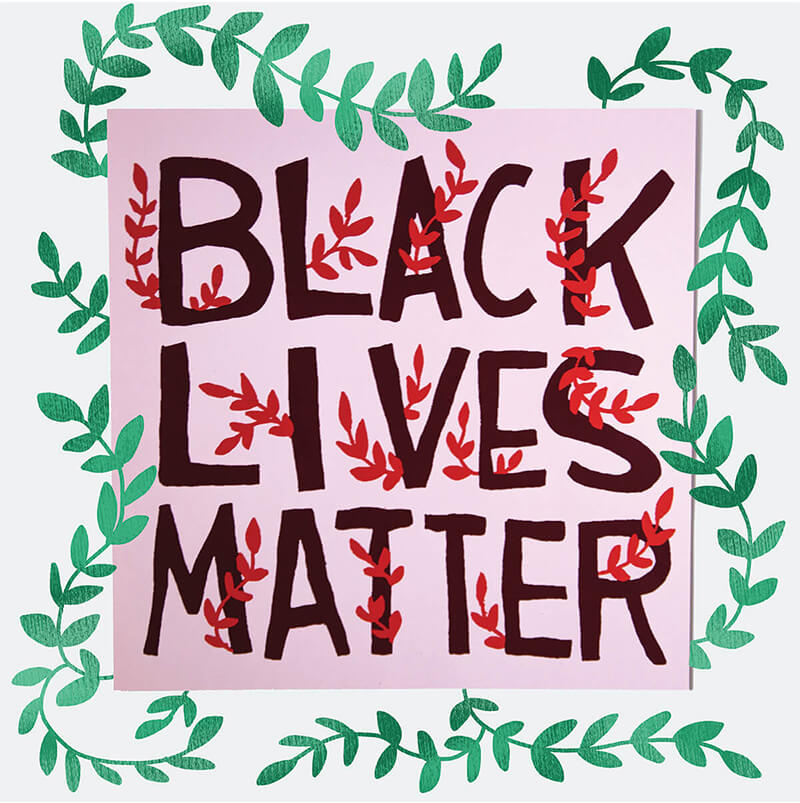

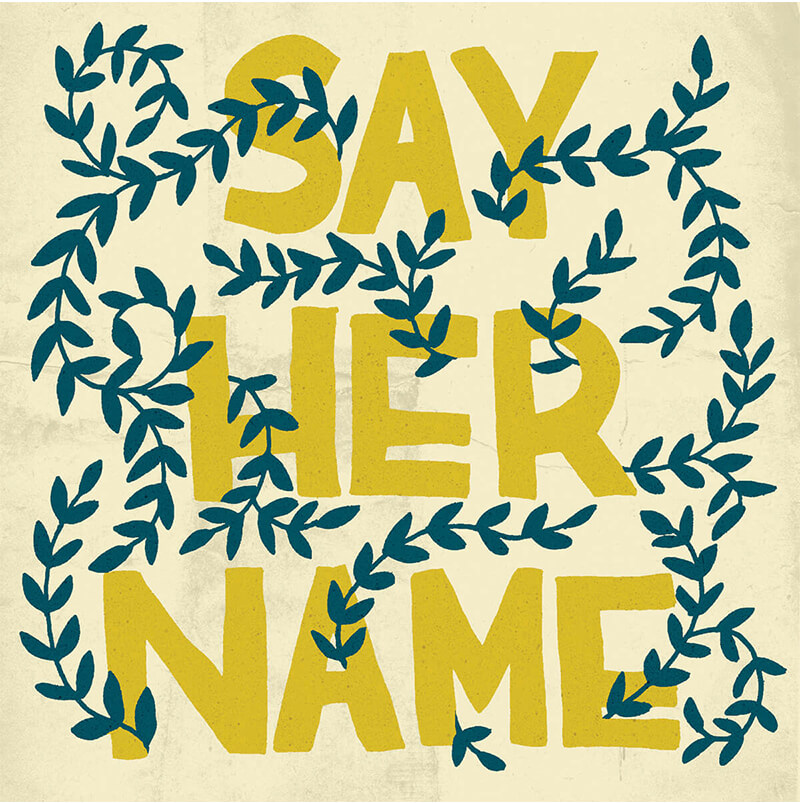

DIRECT MESSAGE

An illustrator uses social media to spread protest art.

POSTERS COURTESY OF CLOSE CALL STUDIO.

IN LATE MAY, Amanda Adams of Close Call Studio turned to her art to declare three simple words in all caps, soft colors, and leafy vines: BLACK LIVES MATTER. She posted the illustrations on Instagram, making them available for free download in hopes that they might be used as posters for the growing number of protests cropping up across the city and country.

“I was trying to figure out what I could do to improve this incredibly corrupt world while also processing my own feelings,” says Adams, who had also just lost her grandmother. Before long, more messages poured out, both personal and political, all hand drawn and digitally colored, as she delved deeper into her own self-reflection.

Despite its myriad downsides, social media has peaked as a place for social discourse and declarations of allyship this year, and Adams' bold messages have resonated with thousands of followers. They have also helped solidify her mission as an artist, which already included donating a portion of her proceeds to charities focused on causes such as the environment and human rights.

“I want to bring people joy, but if I can make people think, too, or feel seen or heard, all the better,” says Adams. “Artists are human, and their opinions matter, and if you have something to say, you can use your skill set to do so. If there’s a way I can use mine to show up, I will do that. I think we all need to.”

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

A culinary artist collects recipes for self-care in COVID.

Krystal mack in

her home. PHOTOGRAPHY BY SCHAUN CHAMPION.

WHEN THE CORONAVIRUS closed Maryland schools in March, Krystal Mack found herself thinking about her own childhood. The news brought back troubling memories of snow days that often meant witnessing domestic abuse at home.

“My first thought was how many kids are seeing this and how many people are experiencing it while everyone else is saying ‘stay home and be safe’?” says the chef and culinary artist behind In Absence Of Studio. “At first, it made me feel powerless. Then I asked myself, ‘What can I do?’”

Inspired by the community cookbooks of high schools and churches, she enlisted friends to help create How To Take Care, which was then free to download for anyone who donated to nonprofits that support victims of domestic violence, to whom copies were also given. Released in April, the collaborative e-guide features fellow artists and chefs, as well as teachers, farmers, and yoga instructors, sharing their recipes and rituals for everything from tea and sourdough to face masks and meditation.

“It shows that self-care is not just for women in linen dresses who do aromatherapy and tarot,” says Mack. “You don’t need googobs of money to find peace and relaxation. It’s something that can be done by everyone.”

Designed with modern fonts and colorful photography, the 100-page limited edition helped raise over $10,000 for organizations like House of Ruth. It also led to virtual summer classes in partnership with Jubilee Arts, and has inspired Mack to think about the new ways she can continue reimagining our relationship with food while still connecting across communities.

“Self-care for the individual is self-care for the collective,” she says. “You can’t care for someone else if you are in a deficit. It’s about having an intimate relationship with yourself and knowing what you need. It’s a constant practice, every day.”

CHANGING TUNES

A rock-and-roll mainstay keeps the music alive online.

Cris Jacobs in his backyard. PHOTOGRAPHY BY JUSTIN TSUCALAS.

OVER THE LAST two decades, Cris Jacobs has stood on more than a thousand stages— with various bands, on festival lineups, all on his lonesome—in Baltimore and beyond. But none of those shows prepared him for that first set of quarantine, when on March 24, he duct-taped his cell phone to a music stand in his basement, sat in front of a microphone, and grabbed an acoustic guitar.

“I didn’t really know what to expect,” says the singer-songwriter. “I’d be lying if I said when the pandemic hit I wasn’t at a crossroads. Everybody’s support and generosity has really blown me away.”

With venues closed, many artists swiftly took to social media for livestream concerts, but few stuck it out like Jacobs, who as of press time had shown up on 29 Tuesdays for solo sets via Facebook Live. That first night, over 1,000 fans tuned in, and months later, a loyal base still follows along, sending virtual tips through apps like PayPal and Venmo, which Jacobs has used to donate to charities and pay his band and crew.

“There’s definitely been a week or two where I didn’t know if I had it in me, but then I think, people are showing up for you, so show up for them, and every time, it’s so cathartic,” he says. “In so many ways, it’s saved my life.”

Jacobs is realistic about the harsh realities ahead for the music industry, from indoor concert limitations to viewer fatigue for virtual programming. But he’s here for the long haul, recently investing in new at-home equipment while relishing this unforeseen time as a stay-home dad.

“This has reaffirmed my belief that people are always going to need music, even if it will be more of an uphill battle to make a living at it,” says Jacobs. “Those things that lift up the soul are more important now than ever.”

COMMERCIAL BREAK

Filmmakers channel public broadcasts in times of quarantine.

WHEN BALTIMORE’S independent movie theaters closed their box offices this spring, filmmakers Thomas Faison and Gillian Waldo channeled their art into filling the cinematic void of the shuttered Charles, Senator, and Parkway. In many ways, “We wanted to give artists a reason to maintain creative momentum,” says Faison.

And so with the help of fellow artists, they launched Quarantv, a free 24/7 television channel featuring an eclectic lineup, from art house films to cartoons to original programming, on the online streaming platform Twitch.

“We’re inspired by the public-access model that offers citizens a way to be creative, while keeping it local and low budget,” says Waldo. “It’s a resource for communities.”

In that vein, their programming, now airing all day on Thursdays, is focusing more on news and politics, hoping to fill another void, this time within the local media landscape.

“Growing up, I remember the Sun as a thicker paper and I mourn the loss of City Paper,” says Waldo. In an effort to better serve the community, they're using their “Primetime Live” segment to break down budget hearings and interview the likes of city comptroller Bill Henry. “We want to see how we can harness this project to build better civic understanding.”

STREETS OF PRIDE

A muralist creates a monument to the trans community.

Jamie Grace Alexander in the middle of her mural. PHOTOGRAPHY BY Schaun Champion.

ON A FRIDAY morning in mid-July, two blocks of North Charles Street were closed off with orange traffic cones as dozens of volunteers assembled in Old Goucher with buckets of paint to declare on the asphalt: BLACK TRANS LIVES MATTER.

“This location is an epicenter for Black trans life, and it needs this message to reinforce that reality,” says artist-activist Jamie Grace Alexander, who co-organized the mural with Baltimore Safe Haven, a neighborhood nonprofit that serves the transgender community. “Those voices do matter, and they need to be uplifted on a large scale.”

Such big, bright letters have been rolled out across the country in the wake of the death of George Floyd, but between East 21st and 23rd Street in Baltimore, this specific message holds particular meaning within the larger Black Lives Matter movement, sparking conversation on a stretch of city street frequented by Black trans women performing sex work as a means of survival.

“When the mural was finished, I felt pride—it’s huge,” says Alexander, who for 10 hours donned a face mask and rode her skateboard up and down the main thoroughfare to inspect each of the 21 capital letters painted in blue, pink, and white—a nod to the Transgender Pride Flag. “My favorite reactions have been from other Black trans people who drive over this street and internalize this message for a full 60 seconds.”

But there’s more work to be done, with the community still in need of better access to housing, job services, and health care. Alexander’s crew experienced street harassment as they added final touches to the mural, which should last for one year.

“At the end of the day, it is a symbol—a visual representation of all the work that we’ve been doing, and a reminder of where the center is,” she says. “What comes after is building worth in the Black trans community . . . As activists, we are going to continue applying pressure to make sure that this statement is true.”