Arts & Culture

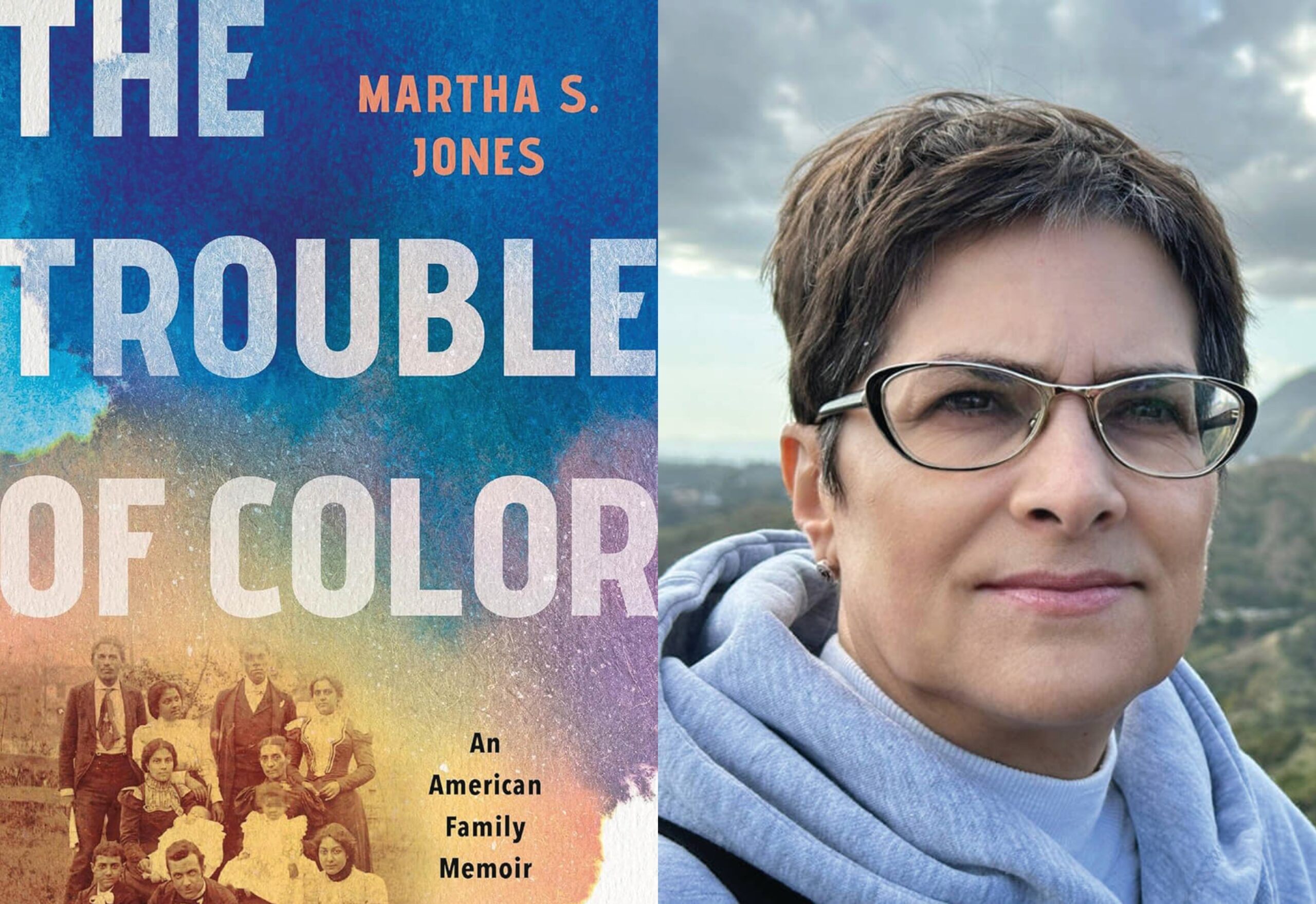

Historian Martha S. Jones’ New Memoir Traces Five Generations of Her Own Lineage

In 'The Trouble of Color,' the Johns Hopkins University professor blends a legacy of enslavement, passing, Jim Crow, and colorism into a complex portrait of an American family in an all-too-often racist land.

Johns Hopkins University professor Martha S. Jones is one of the country’s leading historians and public intellectuals. In Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (2018), she chronicled how free Black residents in Baltimore asserted their citizenship rights, ultimately helping enshrine the principle that all persons born in the United States are citizens. Her 2020 book, Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All, won The Los Angeles Times book prize in history.

Jones’ newest book, The Trouble of Color: An American Family Memoir, tackles a more personal history, however. She investigates five generations of her own lineage, from rural Kentucky to small-town North Carolina to the Long Island suburbs where she grew up, each generation complicated by an ever-evolving color line. With painstaking archival research and graceful prose, Jones blends a legacy of enslavement, passing, Jim Crow, and colorism into a complex portrait of an American family over time in an all-too-often racist land and legal system.

There are people in this book, like your great-great-grandmother Isabella, whose stories I don’t think I’ll ever forget. As an enslaved woman, she gives birth to nine children by the man who owned her. Then, after the Civil War, she has the courage to go to court for child support.

My goodness, right? Isabella endured that hell, if I could put it that way, and she still had the presence of mind to get a complaint written out and take it to the Freedmen’s Bureau. And when she got no satisfaction, she had to find a way to raise her children. When we visit with our ancestors, they challenge us to learn, to understand them, and to live with them. I thought, if she could do that, I surely could learn her story and tell it in a fuller way than she ever was able to, at least on paper.

The anecdote about the college classmate who questions your right, because of your light skin, to be in a Black Studies course becomes more resonate as the memoir moves along.

He may have taught me something [about identity]. He certainly did about how I was going to hear a version of that question again and again across my lifetime. As a scholar of Black Studies, I could give a whole semester of lectures on how to answer that question. A family memoir is another one way to answer that question. The crux of it for me was how personal, how intimate it was, and only later I learned how to think of [race and color] in sociological terms, legal terms, and historical terms. In that moment, the searing part is how personal it feels.

Still, a memoir is a such departure from your previous books.

I had tried to write a family story like a historian, with some objectivity, with some distance, with historiographic questions in mind. I was holding back too much. The example of memoirists, novelists, and poets reminded me there are other ways of writing that let you put yourself and your imagination on the page.

The thing that really opens up the book for a broader understanding of race and color in this country is this legacy of so-called “mixed marriages,” segregation, and the societal rules around “whiteness.” Your parents’ marriage was not the first such marriage in your family.

The story of Mary Jones [a great-great-grandmother, who had lived as a white woman and married a free man of color in 1827], I had heard, but I hadn’t taken it seriously or I hadn’t really thought about what it meant to live by those terms. Then, to appreciate that her story opens up stories of many families, certainly where they lived in Central North Carolina, is humbling. They wrestled with the same questions about not fitting in, culturally and legally, into a nation that had tried to draw this indelible color line between so-called Black people or colored people, and so-called white people.

The current White House administration is banning books and has tried to erase certain stories. Have you considered how timely it is to bring forth these lives and stories that most people would’ve believed were not even knowable?

It’s a strong juxtaposition, right? There’s an insistence, which I hope the book makes, that we can learn and know a lot more than we think. The archives are not generous, but they give up more than they maybe were ever intended to give up, if we work them deliberately. The book absolutely sits for the proposition that there are still stories to tell and that these are American stories.