West Baltimore native Tariq Touré grew up in awe of the businesses in his community—from streetwear designers to eateries like Shareef’s Grill, a takeout restaurant that serves Halal meats and now has multiple locations in Baltimore. “We would come out from Juma [Friday prayer] and everybody would buy his wraps religiously,” recalls Touré, a Muslim husband, father, and award-winning writer.

So when he wrote a poem nearly four years ago describing the story of how the dollar flows through a community, he was drawing from a personal desire to explain that process. Years later, he realized the poem was something he wished he’d had growing up, so he turned it into a children’s book.

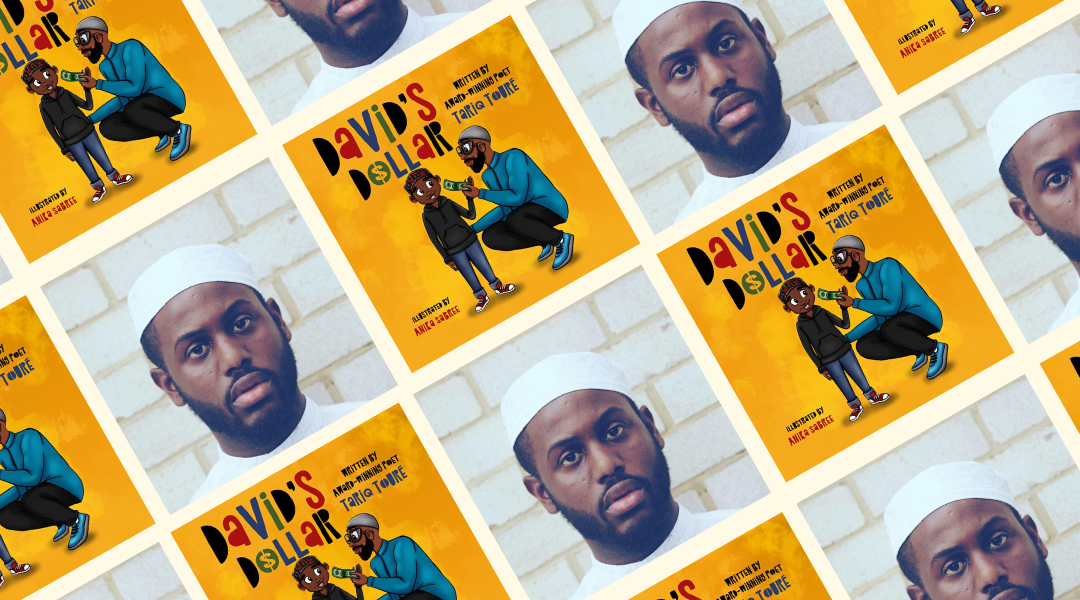

David’s Dollar follows the story of David Kareem, a Muslim kid who expresses curiosity about what happens to a dollar after it’s spent. “He’s happy to have his candy, but he’s sad to see his dollar be spent,” says Touré, who has three children himself. “So his father says, ‘Well, let me show you,’ and then takes him around the neighborhood and shows him all the different businesses, and the dollar happens to keep popping up.”

Slated for a September release (pre-orders are currently sold out), David’s Dollar follows Touré’s two other self-published poetry books. After struggles with publishers who wanted to make fundamental changes, Touré took matters into his own hands. In May, he launched a fundraiser for the illustration costs, which far surpassed its $7,000 goal. The crowdfunding campaign followed his philosophy of “do it for self,” a concept he learned more about through his community, which also happens to be a recurring message in the book.

Despite all of the research, Touré doesn’t plan to sit his kids down and talk about the meaning of the dollar until the book is out. He wants to let them read it and have their curiosity guide a discussion.

“Right now, they know nothing about it,” he says. “I just want them to walk into a room full of books and be like, ‘What’s this?’”

Here’s what the author had to say about his upcoming book, the value of the Black dollar, and Baltimore’s tight-knit Muslim community:

What was your inspiration for David’s Dollar?

Maybe three or four years ago, I wrote a poem that described how a young boy would ask his father how money passes through a community in the realm of [I guess you would say] futurism, because it doesn’t really happen like that right now. [Laughs] Basically, if this was a community where people spent money with each other, how would a young child be able to see that?

So, what prompted you to turn it into a book?

When I was done with it, I thought it’d be something cool to share with my kids at some point in time when they were ready to digest that information. Then I realized, well, I already wrote two poetry books, what would it look like if I were to write a children’s poetry book that tells a really dynamic story that I think people would rally behind?

On the cover, you have David and his father dressed in Muslim garb. Is it important for you that you remain as authentic as possible in your writing?

Building it out autobiographically, it’s important for me to make the way it feels and looks there authentic. [For] Black Muslims, a lot of us dress this way on the regular. A lot of our parents make sure we shop Black on the regular anyway. We get so caught up into representation that we forget we have a dope story that carries with it anyway.

Growing up, were you aware of the disparities in the Black community in Baltimore? I grew up around a lot of hustlers, some entrepreneurs, but very little actual business owners. Sometimes as writers we write for wishful thinking, and it’s like, this is what could possibly be if we spend more money with each other.

When you were younger, do you remember having an understanding of financial literacy?

Not really. The one thing that I feel like was preached in my community was, you know, different income and stuff like that. But as far as walking somebody through it? No, that wasn’t a thing. So it will be good to have literal depictions of how these things work.

What do you think are some of the reasons behind the failure to keep the Black dollar in some communities?

Well, number one, we lack patience sometimes. Papa John’s pizza probably wasn’t fire when he first made it. [Laughs]. We have to believe in the seed that people are planting and understand that it goes through stages, and that people don’t reach perfection off the jump. For whatever reason, we’ve been indoctrinated to believe that, if there are two lemonade stands and one is a white-owned lemonade stand, business there is going to be at a heightened level and [they] therefore deserve that money

What do you think about the timing of the release of this children’s book aligning with everything that’s going on in the world with the youth-led Black Lives Matter movement?

Well, since it’s something that I wrote three or four years ago, it was going to get written regardless—there was a need regardless. It isn’t a “strike while the iron’s hot” decision or something like that. If anybody knows me, they know that I write religiously, so I don’t need a specific moment to spur me to write what I feel is necessary. David’s Dollar was going to be David’s Dollar with or without any sort of a climax of injustice because I believe this is something that is going to need to be revisited constantly by the community. And if it adds to what people are trying to fight for, then, you know, that’s a blessing, too. But I don’t want to get pigeonholed into a “Hey, I’m writing this for this exact thing.” I wrote David’s Dollar because I felt like this story would be useful in the hands of kids like myself who needed it spelled out for them in interesting ways.

What do you hope that people take away from this book?

My goal is for Black children to walk into a store with their parents, see them spend their money, and maybe they don’t even ask the question. In the back of their head, they just say to themselves, “Where did my dollar go? Where did mommy’s dollar go? Where did daddy’s dollar go?”