Arts & Culture

Not Dead Yet

More than a century later, the Ouija board’s Baltimore origin story has been unraveled. Research shows it works, too. (Kind of.)

Charles Kennard always had his eye out for a chance to make a buck, but he was not the greatest, nor the luckiest, businessman.

It appears that he wasn’t the most honest guy, either.

The second child of a successful Delaware merchant, Kennard moved to Maryland’s Eastern Shore in the late 1880s after developing “secret” bone-mix recipes for fertilizer. (In fairness, everyone in the fertilizer business claimed a “secret” recipe.)

Following initial success, his Chestertown plant went to auction due to a combination of drought, competition, and debt. But all was not lost.

A Prussian immigrant named E.C. Reiche kept an office next to Kennard’s on the first floor of the four-story, wood-frame hotel in Chestertown’s tiny business district. A furniture maker turned coffin maker turned undertaker—not an atypical career progression for the day—Reiche was also an inveterate tinkerer and Kennard had another plan.

Back story: Two generations earlier, a pair of girls in upstate New York named the Fox sisters, claiming to be mediums able to interpret mysterious “knocks” from the other side, had launched a spiritualist movement that continued to hold sway across the country.

In fact, in the aftermath of the Civil War, with so many husbands, fathers, and sons lost in the conflict’s bloody battles, spiritualism—the belief the dead can speak to the living—had only gained steam with people desperate for a connection to departed loved ones and greater meaning for their own lives.

It’s in this context in 1886, during the period Kennard and Reiche shared a hallway, that newspaper reports began appearing about a “talking board” phenomenon sweeping Ohio, including an Associated Press story that ran in the local Kent County News.

It’s also about this time, according a later Baltimore American story, that Kennard and Reiche—most likely inspired by the AP account—began collaborating and making at least a dozen of their own “talking” boards.

“Reiche, the biggest coffin maker in town, is making these on the side,” explains Robert Murch, the world’s foremost talking-board historian, and it’s these prototypes that became the Ouija board. “But it’s Kennard, when he leaves Chestertown for Baltimore in 1890, where he continues in the fertilizer game, and starts a real-estate business, who begins pitching what he says is his talking-board invention to potential investors.”

After numerous rejections, Elijah Bond, a local attorney who claimed his sister-in-law was a strong medium, finally took an interest.

Soon enough, the Kennard Novelty Company, which incorporated the day before Halloween 125 years ago, began manufacturing Ouija boards much as they appear today.

Bond was right about his sister-in-law, too: Helen Peters proved convincing enough with Kennard’s new talking board to win over a skeptical U.S. patent office. She not only gets credit for earning the stamp of legitimacy from the federal government, certifying the board delivered as promised, but also for “receiving” the O-U-I-J-A name from the board itself, which told her the strange word meant “good luck.”

(In truth, the name “Ouija” was written on the necklace locket that Peters was wearing at the time.)

So, yes, an undertaker and an opportunist named Kennard invented the only patented board game—billed as both a mystical oracle for communicating with the spirits and wholesome amusement—ever to outsell Monopoly in a given year.

“It comes straight from the 19th-century séances,” says Nic Ricketts, curator at The National Museum of Play in Rochester, NY, noting that a glow-in-the-dark board and a classic version are still sold today. “There has never been another brand board game like it, and I don’t see it fading away any time soon.”

The story of the Ouija board, however, is more than a tale of snake oil salesmen duping the Victorian masses or, subsequently, a game of harmless fun at a million junior-high sleepovers.

While it remains an amazingly enduring pop-culture phenomenon—tied to the rise of the horror movie/paranormal industrial complex—its saga is also about the universal desire to find answers to life’s biggest questions, the history of psychology, and even the development of neuroscience.

“It’s always been a board game, a parlor game, but it has always been more than a board game for some people, too,” Murch says. “In the 19th century, people had a much different relationship to death than we do today—it was much closer to their everyday experience.

“Now, we do everything we can in hopes of avoiding aging, let alone engage in any real thoughts of death. But in the 1800s, people only lived to be 50 years old. Mothers would have 12 children and six of them would die. Their parlor rooms were also their funeral rooms.”

Not surprisingly perhaps, there’s a dark side or two buried in Ouija’s origin story. There always is when money is at stake, and by the early 1890s, some 2,000 Ouija boards were already being sold a week.

William Fuld, who worked for and invested in the Kennard Novelty Company—and eventually gained control of the Ouija business after the founder cashed out too early—went on to make millions manufacturing the board in Baltimore and elsewhere, but only after his brother was cut out of the company.

Their ensuing lawsuits were no mere spat. William’s brother, Isaac, became so embittered that he had his baby daughter exhumed and relocated from the Fuld family gravesite during a cemetery renovation. The two sides of the family would not speak for 96 years.

And, tragically, William Fuld would suffer a fatal accident at his Harford Avenue factory, one he claimed in a 1919 Baltimore Sun story that the Ouija had told him to build. (“Prepare for big business.”)

Overseeing the installation of a flag, an iron railing gave way and he fell off the roof of the structure, which still stands and has been converted into a senior apartment complex.

“On his death bed—the coroner’s report said a broken rib pierced his heart—he made his children promise to never sell the Ouija out the family,” says Murch.

Of course, Fuld’s family did sell—but not for four decades—to Parker Brothers, which promptly moved Ouija to its base of operations in Salem, MA. In 1967, the first year it was headquartered in the town infamous for its witch trials, Ouija sold two million boards.

By comparison, Monopoly—an early version was invented in 1903—wasn’t popular until the Great Depression, when it fulfilled a kind of fantasy escapism. Ouija, on the other hand, was a sensation from the outset, long before even its first film appearances, which date back to Hollywood’s beginnings.

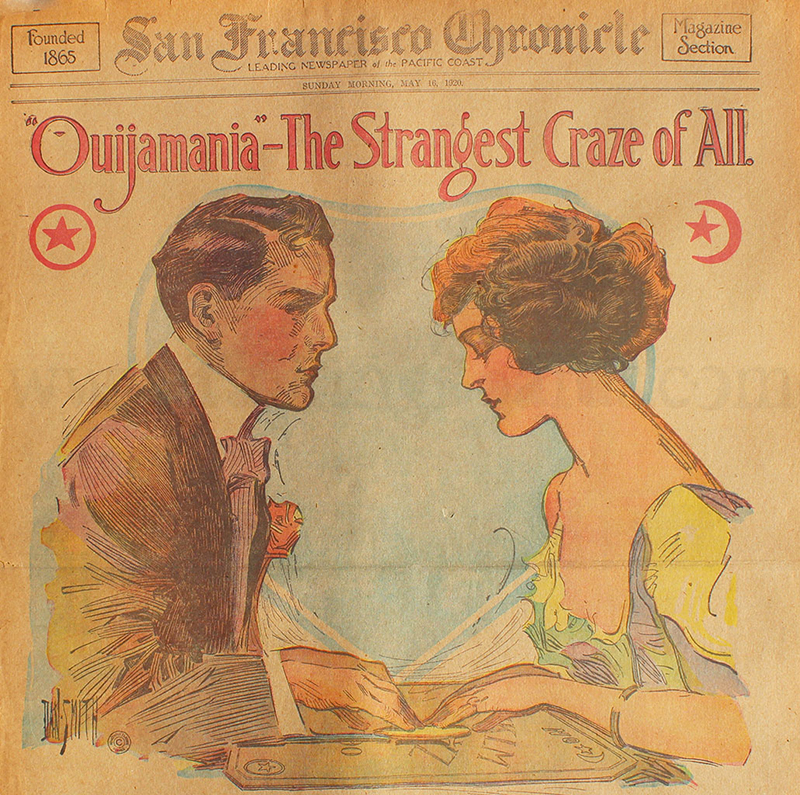

But Ouija’s public image has always been complicated. Initially, the “mysterious oracle” was marketed as a game to enliven a party or encourage a little light-hearted intimacy for romantic—or would-be romantic—couples, who are often depicted in early advertisements with the board resting on their knees as they sit across from each other, both of their hands on the planchette.

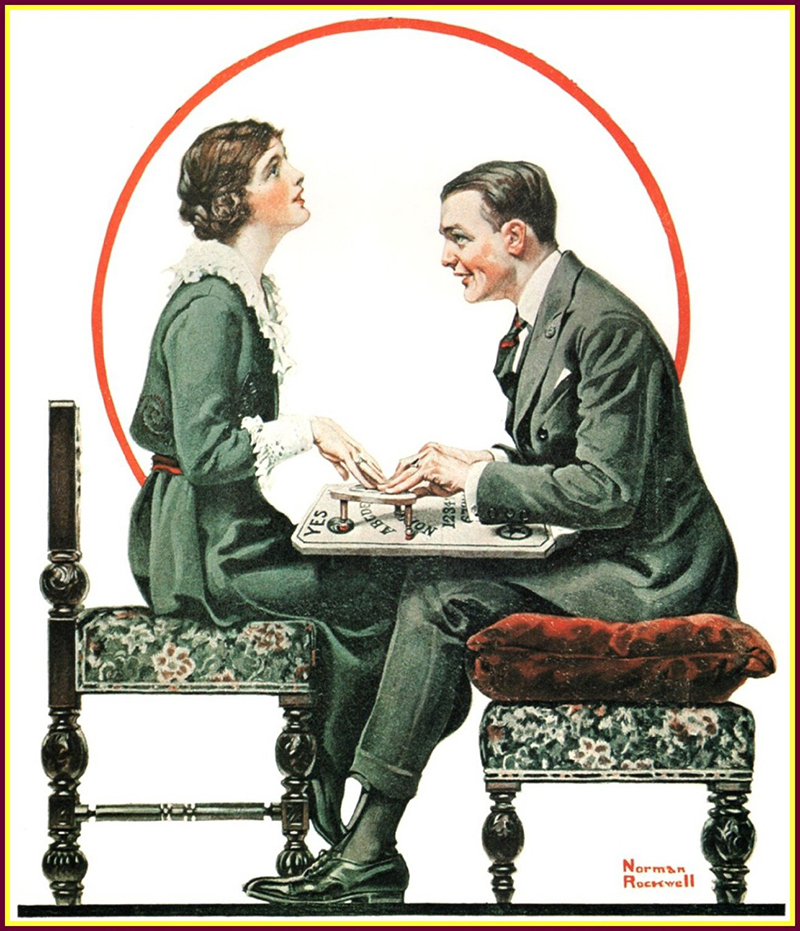

Norman Rockwell, who was fond of depicting the revealing moments of everyday life, painted a well-dressed suitor and young woman, chairs pulled face-to-face, playing with a Ouija board for the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in 1920.

Less well known is the Ouija board’s use as inspiration or as an “automatic” writing tool by acclaimed novelists and poets, such as Sylvia Plath, who wrote “Dialogue over a Ouija Board,” and Pulitzer Prize winner James Merrill. Merrill used notes from Ouija “consultations” in his 560-page epic poem, The Changing Light at Sandover, which contained messages from W.B. Yeats, friend Maya Deren, and the Archangel Michael.

But over time, the relative innocence of the Ouija board—or at least its nonpartisan relationship between good and evil—gave way to a more sinister reputation as Hollywood began utilizing it for darker purposes.

After The Exorcist, in which actress Linda Blair’s character Regan explains to her mom, played by Ellen Burstyn, how she used the family’s Ouija board to ask questions of “Captain Howdy”—the demon who eventually takes possession of her soul—the board’s occult status was cemented.

Since then, it has shown up in more than 20 films, and made countless appearances in the ever-growing number of paranormal-themed TV shows.

Forums around Ouija-associated phenomena populate the internet, of course. Most recently, the 2014 movie Ouija did so well at the box office that Ouija 2 is already in the works. When it was released last fall, the movie so dramatically boosted board sales that petitions by evangelical Christian groups to ban the Ouija started popping up again. Catholic.com, a lay-run Catholic apologetics and evangelization website, describes Ouija as “far from harmless.”

Still, the most interesting thing about the Ouija board might be the latest research around it from University of British Columbia that shows it actually does work—just not in the way we might assume.

A few years ago, Sidney Fels, professor of electrical and computer engineering at UBC, brought out a Ouija board at a Halloween party attended by graduate students, including many who were foreign-born and unfamiliar with how it works. They assumed it required batteries.

“‘No, you don’t need batteries. It will move,’ I told them,” Fels recalls. “I gave them some mystical explanation tied into Halloween and they had a good laugh.”

But lo and behold, when Fels returned later, the grad students were enthralled because the planchette was moving on its own. Or so it appeared.

The mechanism at work was actually something known as the ideomotor effect, which refers to the influence of the unconscious mind on muscle movements. (First identified in 1852, preceding Sigmund Freud’s theory of the unconscious mind by decades, Dr. William Benjamin Carpenter discovered the ideomotor effect while investigating the unconscious mind’s ability to direct motor activity. Shortly thereafter, other researchers began linking that discovery to—you guessed it—spiritual phenomena.)

Days later, still fascinated by the students’ experience, Fels shared the story with colleague Ron Rensink, a psychology and computer science professor, and that got the ball rolling about whether the board could serve as a tool to look at unconscious knowledge.

“We didn’t know if we’d find anything, but when we did, the results really surprised us,” Fels says.

When study participants were asked to answer or guess at a set of challenging questions, they were correct about 50 percent of the time. But when responding while using the board—which participants believed had the ability to “receive” correct answers from another person teleconferencing via a robot Ouija partner—they scored correctly upwards of 65 percent of the time.

In actuality, the robot was a ruse; it was not responding to the video-conferencing player, but subtly amplifying the study participants’ tiny, unconscious movements.

“It was significant how much better they did on these questions,” Rensink says. “If you don’t think so, consider the difference playing roulette when the odds are 50-50 versus 65-35.”

The implication is that one’s unconscious is much smarter than anyone knew, capable of pulling up bits of stored information not accessible to the conscious mind.

Results in a follow-up study replicated the findings, which they reported in the academic journal, Consciousness and Cognition.

Rensink believes the results open greater possibilities for further study. For example, is unconscious memory affected by Alzheimer’s and other neurodegenerative diseases in the same way as conscious memory?

It’s work that William Fuld—the guy who fell from the factory roof and is considered the “father” of the Ouija (he was also a state delegate and philanthropist)—would probably appreciate. When asked directly by a reporter if he believed in the Ouija’s mystical powers, he replied: “I should say not. I’m no spiritualist. I’m a Presbyterian.”

The discovery of the Ouija’s ability to tap into unconscious knowledge is not the only development in the talking board’s 125-year-old story, however. The reconciliation of William Fuld’s family with his brother Isaac’s clan after nearly a century of silence is the other compelling occurrence.

The two sides had long lost contact until Murch began posting his research on the web nearly two decades ago. That’s when Stuart Fuld, the then-sixty something grandson of Isaac Fuld, and Kathy Fuld, the granddaughter of William Fuld, separately reached out to Murch, in hopes of learning more about their ancestors.

“I was talking to each one individually at first without the other one knowing it,” Murch recalls. “I was aware of the feud and didn’t want to upset either one, but then Kathy called one night and asked for Stuart’s phone number.”

“It turned out we were living five miles apart while growing up and didn’t know it,” says Kathleen Fuld, Stuart’s wife. (Stuart Fuld passed last year.)

The two sides of the family, which now include great-grandchildren and great-great grandchildren of the brothers, have been getting together regularly ever since.

While some of the descendants did hold on to Ouija and other talking-board memorabilia—Isaac later attempted to launch a talking board competitor named the “Oriole” board—no one, apparently, ever took a serious spiritual interest in Ouija. Not even when they were kids.

“Not me,” says Kathleen Fuld, chuckling. “I was a good Irish Catholic girl. I had eight cousins who were nuns.”

She adds, however, that Stuart did take a great deal of interest in learning about his grandfather and ancestors, as well as the history of the former family business—if not the surrounding mysticism—especially as he got older.

“I’ll tell you a funny story,” she says. “We went up to the Poconos for a golfing trip one year and there was a conference of priests taking place at the hotel where we stayed. I don’t remember why or how it came up, but Stuart ends up telling a group of priests we’re talking with that his family once made the Ouija board.

“All the priests immediately started making little crosses with their fingers,” Fuld continues. “They started asking Stuart all kinds of questions. They wanted to know the whole story and got the biggest kick out of that.”

Even better, the priests invited the couple to take advantage of the conference’s complimentary evening cocktail parties for the weekend—which they did.

“But it didn’t matter,” she adds. “Every time we saw those priests, in the elevator, or wherever, they’d start making those crosses with their fingers.”