Flaunting long, feathered earrings, her silvering hair tucked in a high bun, Christina Delgado relaxes on a green loveseat encircled by family mementos. Funky music blares and the smell of incense lingers.

“That’s my mom when she was in the military,” says the native New Yorker, artist, educator, and cultural worker, pointing to a portrait on the purple wall behind us. “That’s my uncle Jerry, who was her favorite brother. Those are my parents when they first started dating. And that’s me and my mom.” She giggles, pointing to a white pullover sweatshirt with their smiling faces on it, which reads “Double Trouble.”

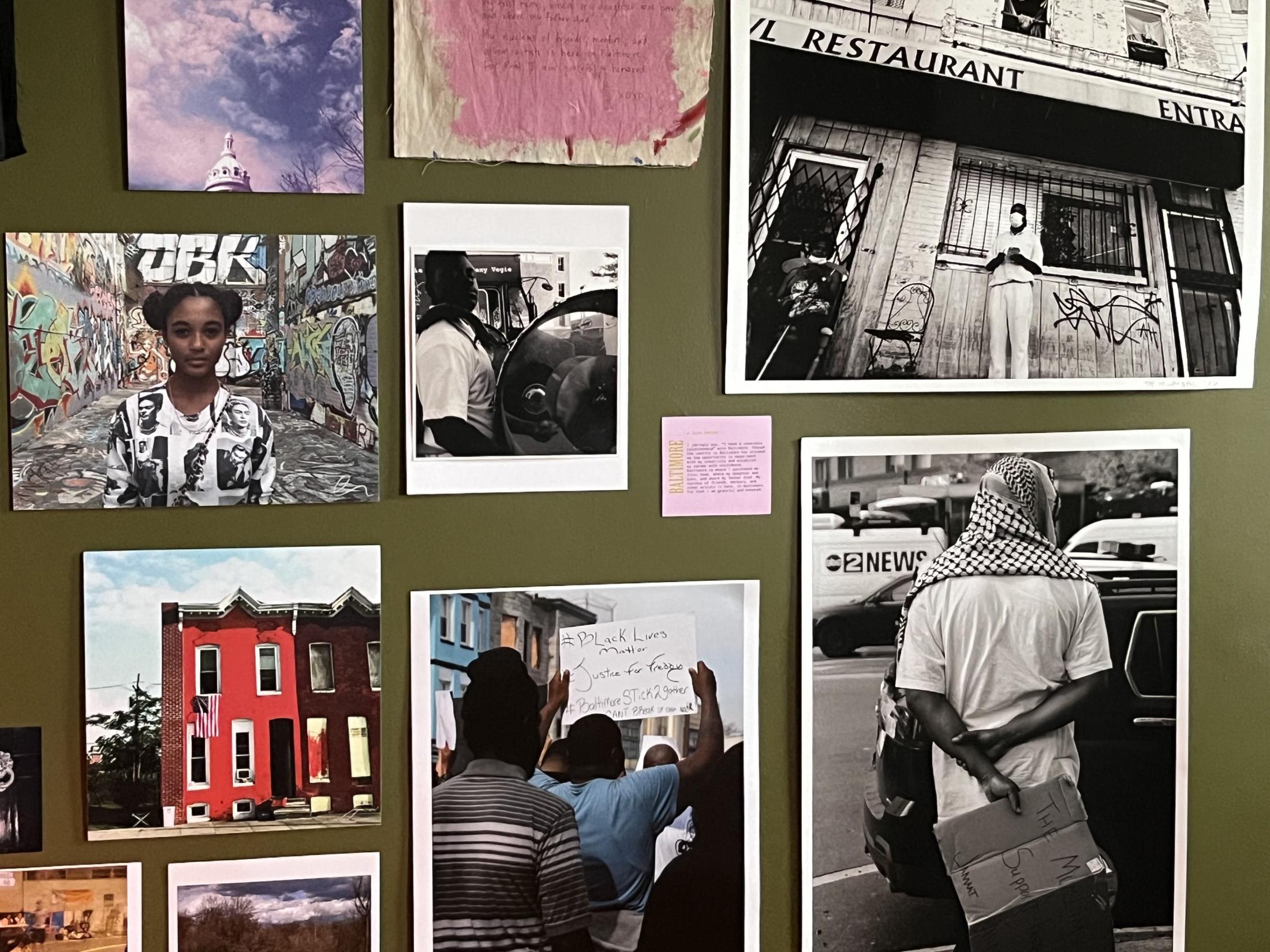

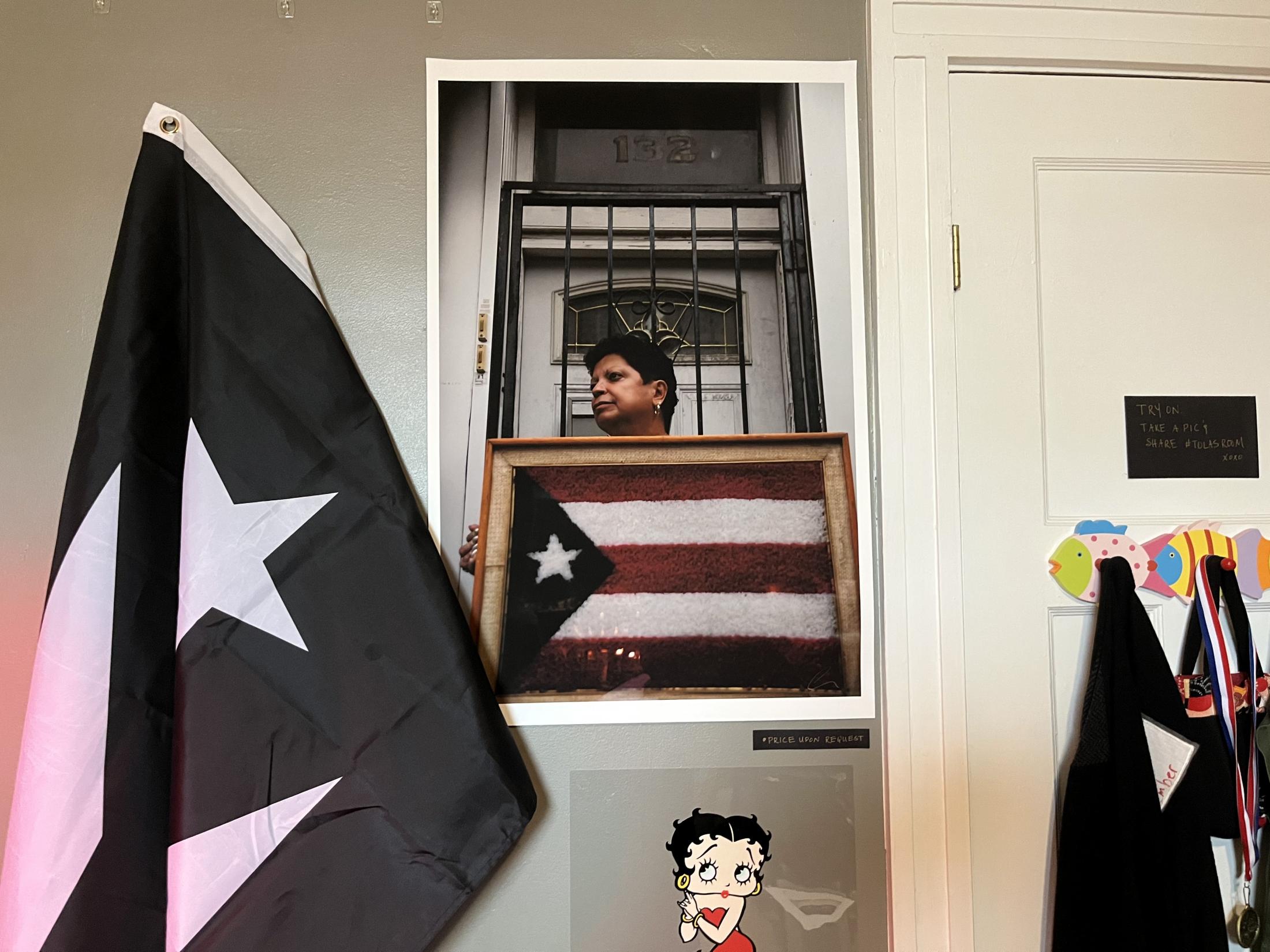

Adjacent to the living room—which houses literature on Baltimore’s Black and Puerto Rican roots—is a multimedia collage of photographs, framed artwork, Post-It notes, and religious keepsakes. Infographics offer guests a truncated overview of the influence of Puerto Rican culture throughout American history.

This is Tola’s Room. Purchased in 2006, it was previously the house where Delgado lived with her now 11-year-old daughter, Omotola (Tola for short). Last summer, she transformed the Northeast Baltimore rowhome into an immersive, three-floor Puerto Rican museum and cultural education center.

Open to the public Sundays from 12-5 p.m., the Belair-Edison museum also offers special programming, including bi-monthly “Tranquilo” yoga classes (with smoothie bowls prepared by Tola); community workshops (one recently focused on navigating elder care); and group tours (the Girl Scouts of Central Maryland recently stopped by). The space also provides a home for the work of Delgado’s Bmore Boricua Project, a series of curated events designed to gather artifacts and oral histories showcasing Baltimore’s Puerto Rican narrative.

As much as Tola’s Room is a resource for Baltimore’s Diasporican (Puerto Rican residents) and those looking to learn about the culture, on a personal level, curating the space has been deeply meaningful to Delgado, who is “technically biracial” (both Puerto Rican, her father had dark skin and her mother—of Dutch and Italian descent—has lighter skin) and grew up without a full understanding of her own heritage.

“We were Puerto Rican, but definitely had this pride of being Americanized,” says Delgado, a second-generation Nuyorican, meaning she was raised as part of New York City’s Puerto Rican community. “I don’t speak Spanish fluently, so, as a child, there was a bit of a detachment in that way. It wasn’t until my father passed away that I became more confident in my own culture.”

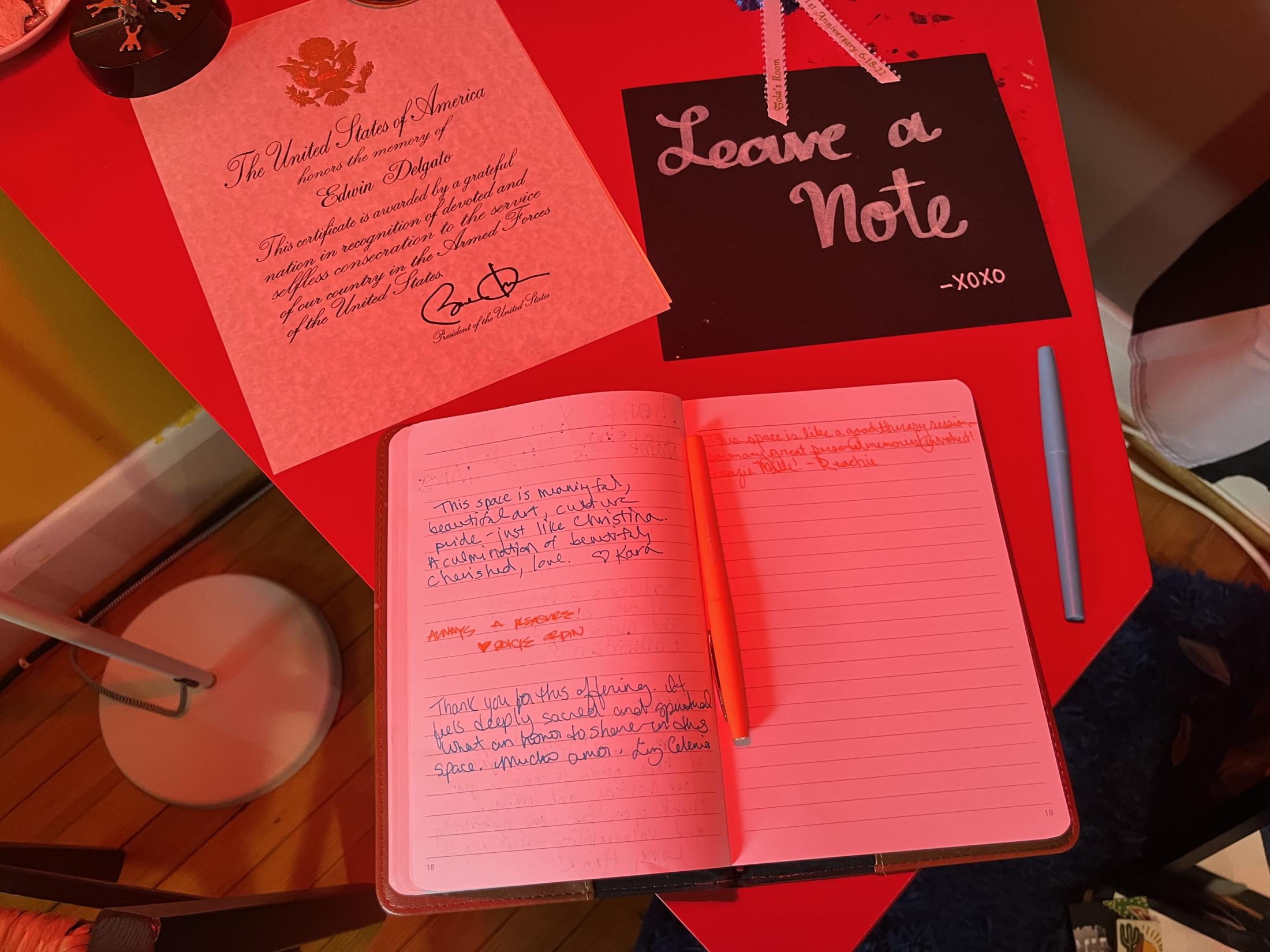

Her father, Edwin, died in 2013—just one day shy of Omotola’s first birthday. Soon after, Delgado was left to unpack a trove of his belongings that had been untouched for decades. Though daunting to tackle while in mourning, sifting through her father’s keepsakes—including relatives’ birth and death certificates, saved prayer cards, and vinyl albums that the pair would listen to throughout Delgado’s childhood—eventually became therapeutic.

“I had an attachment to all of these things, because I knew that he had an attachment to them, and I wanted to be able to share them,” Delgado says. “My goal was to create a space with some kind of connection to my family. And because I was defining this space as a museum, I wanted to be intentional about learning about my Puerto Rican culture.”

She began curating the museum in 2014, and opened it to the public in June 2021 with an inaugural one-floor exhibit titled Puerto Rican Passion—an interactive exploration of home and family that included live music and traditional Puerto Rican food and drinks for guests.

It’s been said that grief is unspent love without a place to go. But through the museum, Delgado found a space for that love for her father to live. Upstairs, Tola’s former bedroom now houses Edwin’s belongings. It has everything that made him special: heirlooms, yes, but even mundane things including mouthwash, which he didn’t go a day without. “It’s kind of like the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding, where Windex was the cure-all,” Delgado quips. “Listerine was my dad’s cure-all.”

There are snow globes, stuffed animals, napkins (he would always carry napkins or a paper towel), the red Papasan chair he bought Delgado when she moved into her first apartment, and CDs for guests to rummage and dance along to. “Dance like he would,” is written directly on the wall, as a tribute to Edwin. Other interactive features include a chalkboard where guests can write messages and process the experience of moving through the space.

The basement is also extremely personal to Delgado. Christening outfits worn by both her and Tola—previously featured in a performance art exhibit titled Ropa Vieja—hang side-by-side on a wood-paneled wall next to Tola’s pink and blue receiving blanket, newborn hat, and baby photos from Delgado’s baptism.

Fittingly named after her daughter—Omotola translates to “child is wealth, one of worldly wealth,” in Nigerian (Tola has Nigerian lineage on her father’s side)—the museum was designed by Delgado as an interactive storybook to help her, and future generations, understand their lineage.

“She’s my everything,” Delgado says of Omotola, crying. “She’s a creative child. She’s a beautiful soul. She is my dad. People who knew my father gravitate toward her because she looks so much like him. Every parent feels this way, but she’s everything I’m not and everything I am.”