Food & Drink

By Suzanne Loudermilk

Photography by Christopher Myers

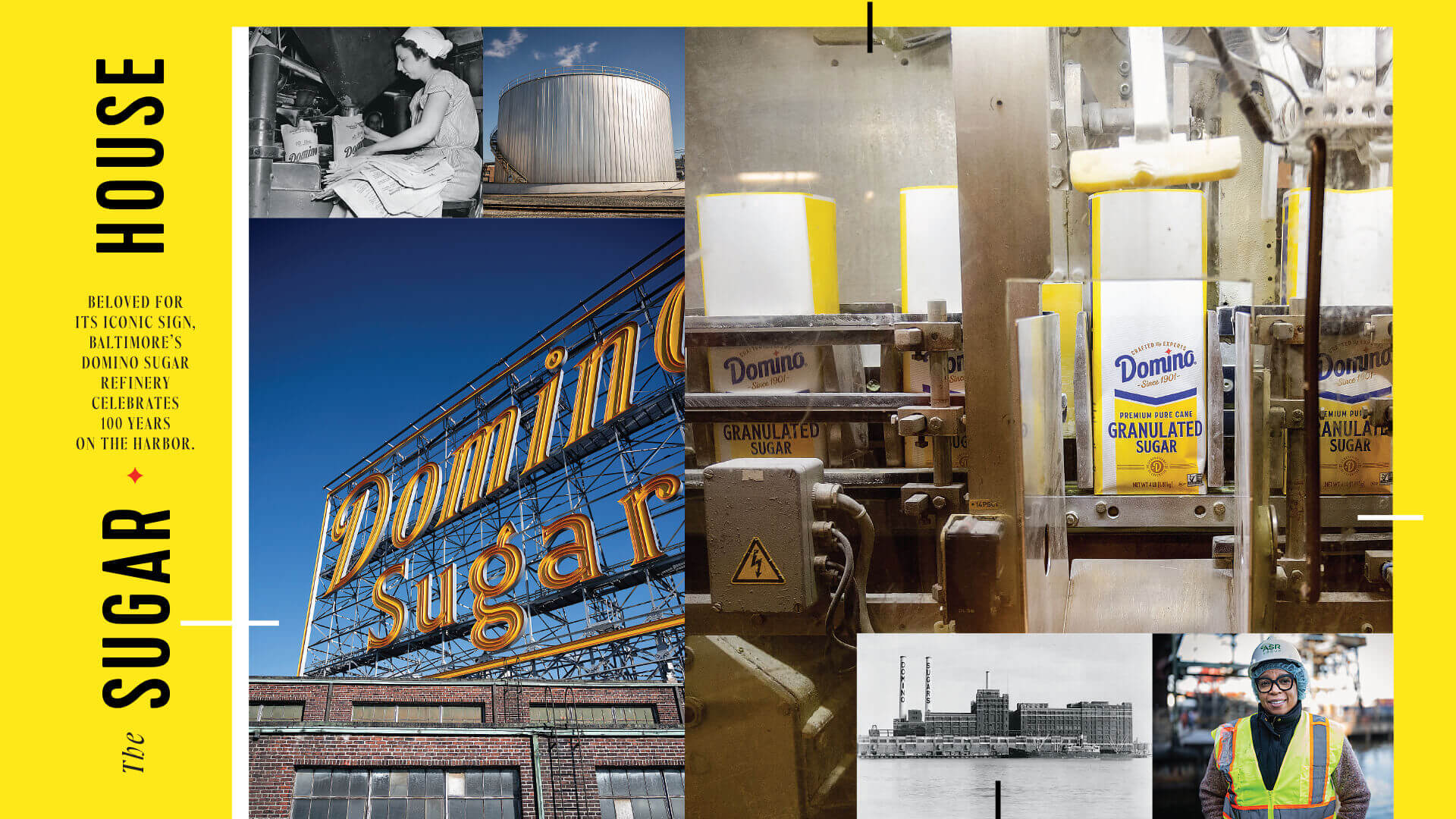

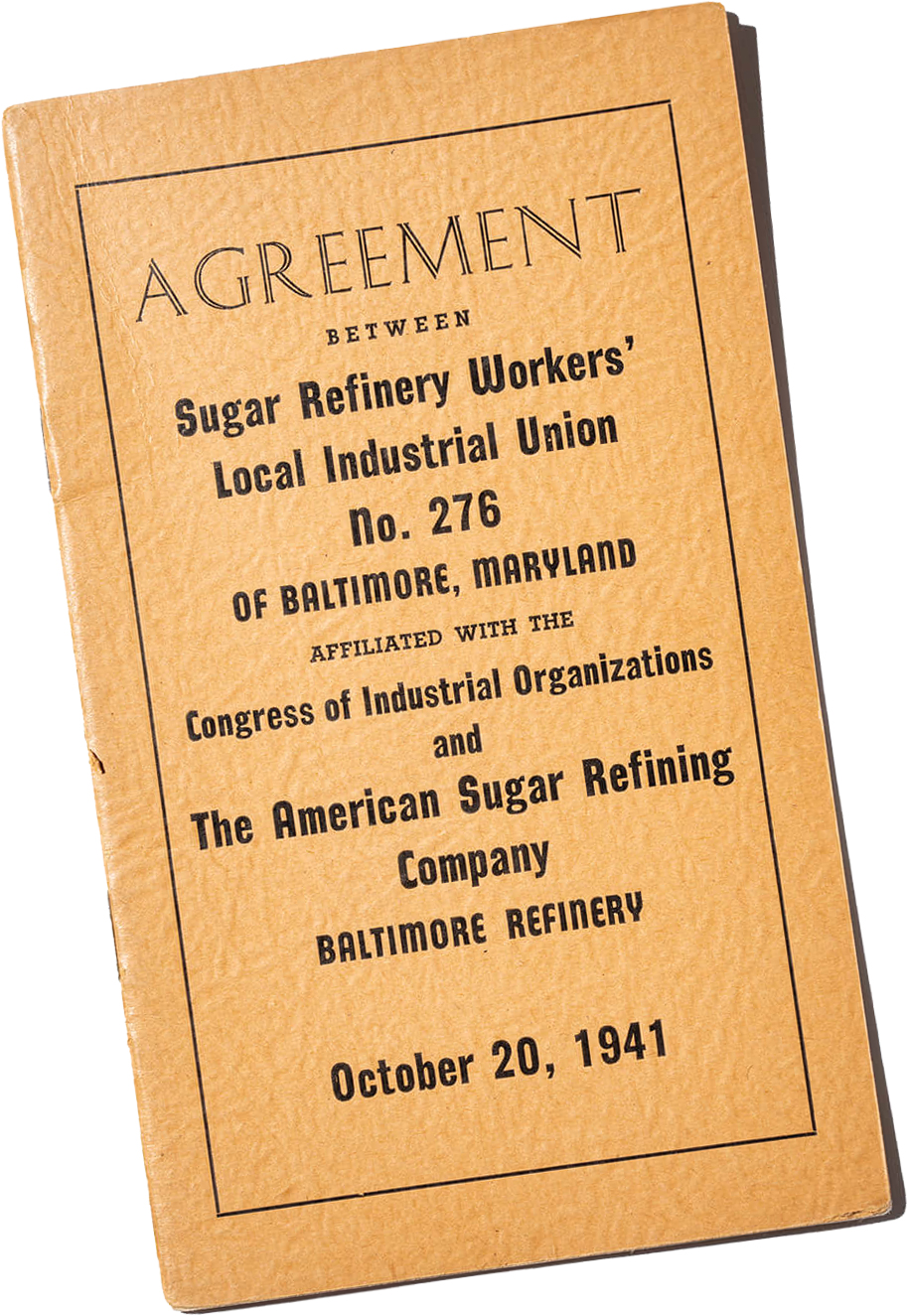

✦ OPENING IMAGES

Filling 10-pound bags of sugar, c. 1950s; a molasses storage tank; sugar bags being filled in modern day; Coricka White, Domino's first female refinery manager; the refinery, c. 1930s; the newly refurbished Domino Sugars sign as it stands today.

often before the sun creeps above the horizon, crime novelist Laura Lippman strides along Baltimore’s quiet waterfront on her two to three mile walk.

Her route varies, but there’s one constant— the reddish-orange glow of the “Domino Sugars” sign. “It’s capable of this optical illusion, which seems to follow one around the harbor,” she says. “You can see it from so many vantage points. It’s kind of surprising that way.”

When Lippman learned the 70-year-old neon-bulbed landmark would be taken down early last year for a spiffier, more sustainable LED-powered version, she decided to document the old beacon as it was being dismantled, capturing it from different angles on her iPhone and posting it on Twitter while most of her followers were still asleep.

“It just became this fixture on my daily walk,” she says, noting that she quickly embraced the new one when it was installed last July. “I always saw it as emblematic of what Baltimore thinks it is—a blue-collar, working-class town. If it was ever true, it hasn’t been true for a long time.”

✦ Leaders of the American Sugar Refinery Co. and the B&O Railroad Co.

pay a site visit to the Domino refinery, 1922.

Lippman is right. Since the mid-20th century, Baltimore’s manufacturing scene at the harbor has changed dramatically. Factories like McCormick & Company, Allied Chemical Corp., and Procter & Gamble left the harbor. Former mills and warehouses have been reborn as condominiums and restaurants, a once-thriving Harborplace replaced weather-worn docks, and gleaming office towers altered the skyline. But throughout the transition, Domino Sugar, now the Inner Harbor’s lone manufacturer, remained exactly where it has been for the past 100 years, poised to continue its operations for another century.

“It came down to demand—the deep-water harbor, access to trains and later a network of highways, and a skilled workforce that allowed the plant to get sugar to various places,” says Peter O’Malley, vice president of corporate relations for Domino’s parent company, American Sugar Refining Inc. “We’re not going anywhere.”

All of those factors allow Domino’s line of 40 products—from white sugar and confectioners’ sugar to brown sugar and specialty sweeteners—to be distributed throughout the Mid-Atlantic, into New England, the Carolinas, and west to Chicago. The Domino Sugar visionaries knew what they were doing when they decided to build a plant in Baltimore.

✦ The raw-sugar shed

holds heaps of the stuff, waiting to be refined.; four-pound bags move down

a conveyor belt.

onstruction of the Baltimore factory began in 1920 on

21 acres along Key Highway East in Locust Point, near

a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad terminal, and along a

quarter mile of the mouth of the Patapsco River, our

harbor. Streetcars on Fort Avenue, a block away, transported

workers to the site, once the home of a pottery factory, a

fertilizer company, and a shipyard. No one called it the Domino

Sugar refinery then. It was simply referred to as the American

Sugar Refining Co. plant, in deference to its original owners.

There was no signature “Domino Sugars” sign either. That

wouldn’t happen until 1951.

onstruction of the Baltimore factory began in 1920 on

21 acres along Key Highway East in Locust Point, near

a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad terminal, and along a

quarter mile of the mouth of the Patapsco River, our

harbor. Streetcars on Fort Avenue, a block away, transported

workers to the site, once the home of a pottery factory, a

fertilizer company, and a shipyard. No one called it the Domino

Sugar refinery then. It was simply referred to as the American

Sugar Refining Co. plant, in deference to its original owners.

There was no signature “Domino Sugars” sign either. That

wouldn’t happen until 1951.

When it opened in 1922, the Baltimore business community hailed the modern-day factory with its more than 700 workers: “It is the biggest thing that has come to Baltimore since the establishment of the steel plant at Sparrows Point,” Howard Bryant, president of the Baltimore City Council, told The Baltimore Sun.

At the time, Domino Sugar was one of many manufacturing plants in Baltimore City, including The Stieff Co. silversmiths and Bromo-Seltzer. But as factories closed or moved to other locations, the city’s economic drivers changed. Now, Johns Hopkins University and Hospital are Baltimore’s major employers instead of companies like Bethlehem Steel, once the city’s largest employer.

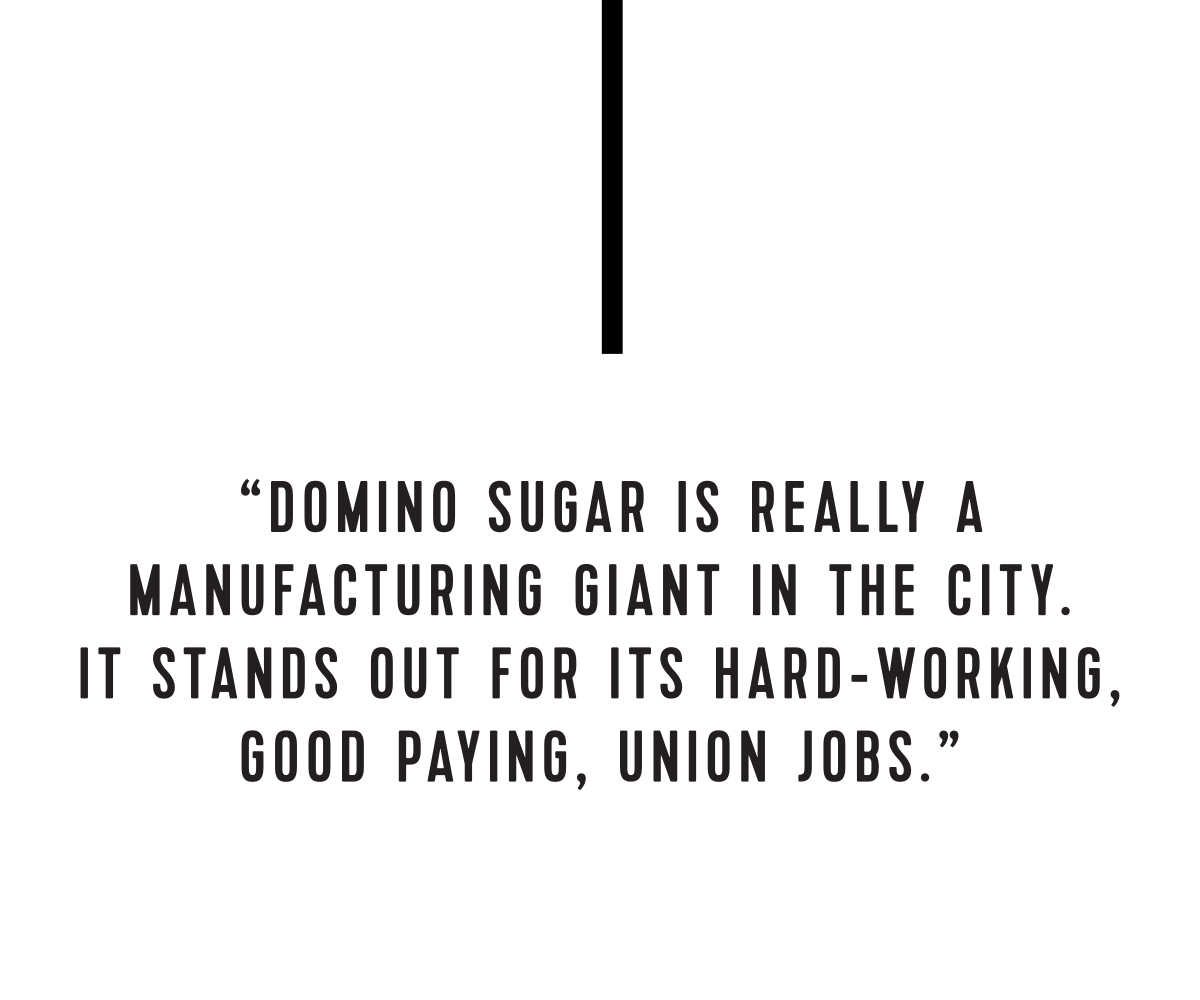

“You lose the variety of jobs in the city when you get away from manufacturing jobs,” says Claire Mullins, director of marketing at the Baltimore Museum of Industry, which displays several old-timey Domino Sugar products, plus the 190-pound, five-foot-tall neon dot that was above the “i” in the old sign. “Domino Sugar is really a manufacturing giant in the city. It stands out for its hard-working, good paying, union jobs.”

Workers at the refinery can earn from almost $26 an hour to an average salary of more than $75,000 a year. In 15 buildings, now spread across 30 acres, Domino Sugar’s 500-plus employees hold a range of positions, from clerical to crane operator.

✦ Unloading raw sugar at the

dock, c. early 1900s.

Kim Abell, 62, started working at the company when she was 17, following in the footsteps of her dad, who oversaw the plant’s storerooms for almost two decades before retiring. She began as a summer intern in the billing department three days after graduating from Parkville High School. Today, the Fallston resident is a senior administrative assistant in operations. “It’s like a family,” says the mother of two, who credits her job for enabling her to put both daughters through college. “They try to give you that work and homelife balance.”

When Abell started at Domino Sugar 45 years ago, there were no computers. Calculators and telephones were the office machines of the day. Everything was done manually, she says.

But these days, automation rules. The refinery is a beehive of 24/7 activity behind its austere, brick exterior, with three round-the- clock shifts to keep it all going. The plant’s multiple buildings are of varying heights and named after the jobs performed in them.

✦ Local union

agreement, c. 1941.

For example, the temporary raw-sugar shed (the previous one was destroyed in a three-alarm fire last year, and a new $25-million shed is being planned) holds the unrefined product, which is delivered by ocean-going ships, carrying payloads upwards of 90 million pounds, 42 times a year from ports like Florida, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Africa. Once a ship docks, crane operators transfer the raw sugar—which has been extracted from sugar cane prior to arriving at the refinery—from the vessel to the raw-sugar shed, where the towering mounds of brownish grains look like the giant beach dunes of North Carolina’s Outer Banks.

About 885,000 tons of sugar are refined at the Baltimore refinery each year, a process that involves washing and filtering the raw sugar to remove impurities, then crystalizing and drying it. On a daily basis, more than six million pounds of white, brown, and liquid sugar are produced to satisfy the 17 teaspoons of sugar that Americans consume each day in products like soft drinks, sweetened snacks, and condiments.

✦ 2,000-pound

bags of sugar for commercial

food makers; engineer Megan

Alley; a roll of paper sugar bags;

a crane discharges raw sugar

from vessels.

Kevin Garnett, known as “Pop Pop” around the plant, worked at Bethlehem Steel before arriving at Domino Sugar with a resume rich in operating heavy equipment and machinery. But he was unaware how the company’s products were made. “I didn’t know sugar went through so much process—I just thought they bagged it up,” he says with an easy laugh. “I had to learn how everything works.”

These days, Garnett, a 62-year-old Baltimore native who lives in Rosedale, drives a front-end loader as a raw-sugar operator. Inside the raw-sugar shed, he scoops up a mound from the sugar pile with his equipment and places it into a large hopper that holds the sugar until it falls onto a conveyor belt, which then transports it to a bucket elevator. From there, the sugar moves on to another building—the wash house—to begin the refining process.

✦ Collection of vintage sugar tins, c. 1970s; antique wooden create for cane sugar, date unknown; back of a mid-20th-century Domino recipe book.

After 19 years at the plant, Garnett now knows a thing or two about the process and relishes his role as an experienced driver and a union shop steward. “I try to keep everyone doing the right thing,” he says, genially. “I’m sort of like their leader.” Hence the grandfatherly nickname bestowed upon him. He has also brought his son, Terrell, into the refinery, where he works in the labor pool, performing maintenance tasks throughout the plant.

The 10-story Domino Building, the main structure in the complex, contains the packaging machinery and storage facilities—the last stop before the products go to a warehouse for distribution. It also supports the signature 120-by-70-foot sign on its roof. Unlike the company’s name, the grid’s letters spell out “Domino Sugars,” with the plural ‘s’ being a holdover from old marketing of the 1950s, when the sign was first erected.

Charlotte Hardy, who has been a laboratory analyst at the plant for 52 years, was honored for her lengthy tenure by being asked to switch on the new sign on Fourth of July last year.

“As we got closer to the day, the excitement started to build,” says Hardy, who analyzes the raw sugar for sucrose content and impurities from the time it arrives at the wash house to the finished product. But then she became nervous, especially when she had to stand on a wooden platform on the Domino Building rooftop, knowing hundreds of viewers were waiting to see that familiar glow from the iconic symbol. “What if the lights don’t come on?” she remembers thinking. “What if I don’t hit it exactly right?”

She had some reason to be nervous. When the sign started coming down, many Baltimoreans worried they were losing a piece of history. But as most of the city knows, the illumination went off without a hitch.

Hardy, who is 74 and lives in the Towson area, began her career at the plant after graduating from Southern High School. At the time, she lived in Locust Point, where many of the Domino Sugar workers lived (today, 18 employees call the community home), and a neighbor told her that Domino Sugar was hiring. She didn’t expect to stay at the company this long but says, “I enjoy the work, like the people, and the benefits are really good—I never saw a reason to leave.”

Inside the Domino Building, safety equipment is de rigueur, from hard hats and orange reflective vests to safety goggles. And there’s good reason. Like many factories, the refinery hasn’t been without its tragedies. A worker was killed in a forklift accident in 2009, an equipment operator died after being doused with calcium hydroxide in 2000, another worker was seriously injured when his arm was caught in machinery in 2012, and, in 2007, three employees received minor injuries in an explosion.

On any given day, the building is a whir of motion with conveyor belts constantly moving, forklifts beeping, and sugar—lots of sugar—being poured mechanically into distinctive bright-yellow-and- white containers of all sizes, including four-pound plastic tubs made only at the Baltimore plant to 2,000-pound sacks destined for commercial bakeries. Small sugar packets churn out upwards of 3,000 a minute and 150,000 four-pound bags are produced each shift.

Amid the often-deafening noise—ear plugs are a must—the factory also has a familiar odor. At first, you can’t quite name it, then it hits you: crème brûlée.

Even outside, neighbors can pick up the sweet scent. “When the ship is in and there’s wind,” says Sam Cogen, president of the South Baltimore Neighborhood Association, “you can taste and smell sugar in the air.”

✦ A storage tank holds

molasses used for brown sugar; cranes

wait to unload raw sugar along the

Baltimore harbor.

merican Sugar Refining Inc.—a subsidiary

of ASR Group International

Inc., the world’s largest refiner of sugarcane—owns the Baltimore plant

and has two additional U.S. refineries

producing Domino sugar—its largest in Chalmette,

Louisiana, and another in Yonkers, New

York. In 2001, ASR bought Domino Sugar, which

was then owned by a British company.

merican Sugar Refining Inc.—a subsidiary

of ASR Group International

Inc., the world’s largest refiner of sugarcane—owns the Baltimore plant

and has two additional U.S. refineries

producing Domino sugar—its largest in Chalmette,

Louisiana, and another in Yonkers, New

York. In 2001, ASR bought Domino Sugar, which

was then owned by a British company.

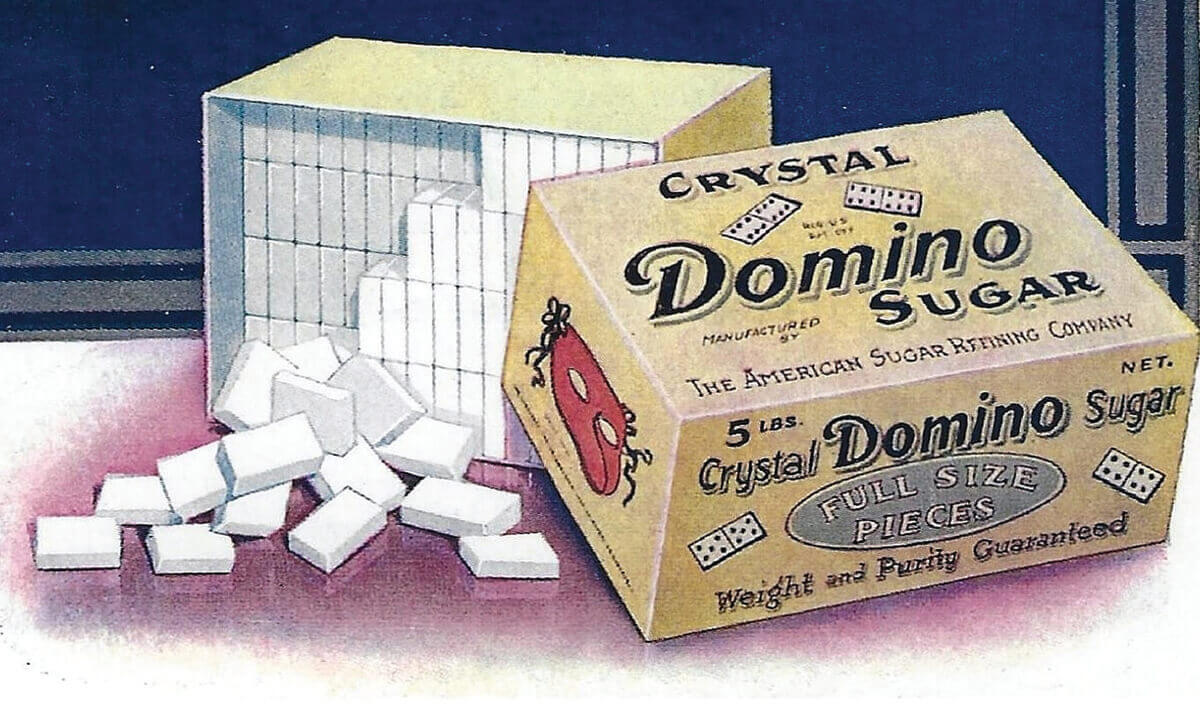

The Domino name was officially adopted in 1901, with one anecdotal story claiming that it was chosen because its sugar cubes were reminiscent of the tiles used in the old-school game of the same name. The company opened its first plant in 1856 in Brooklyn, New York, producing 98 percent of the sugar consumed in the United States. It closed in 2004 as manufacturing in the area changed.

When Domino Sugar arrived in Baltimore, it wasn’t the city’s first sugar refinery. At one time, there were six separate plants throughout the city. In Colonial days, several small refineries produced sugar for local consumption, but as new methods were developed by the 1850s, production increased as boats carrying raw sugar from the West Indies were able to easily maneuver Baltimore’s deep harbor and railroads could deliver the refined goods.

In 1871, The Baltimore Sun called sugar refining “important to the general trade of the city,” which was also known for its canning and fertilizer factories. Still, the heyday didn’t last long. In 1873, the local industry began to collapse as the owner of the largest Baltimore sugar plants declared bankruptcy.

Domino Sugar brought about a sweet revival when it began operations on April 3, 1922. At the time, William F. Broening was mayor, Model T cars were popular, and the Baltimore harbor was bustling with wholesale seafood markets and ships unloading bananas from Central America, oranges from Florida, and coffee from Brazil.

✦ Advertisement from the early

1900s shows how the Domino name was

chosen, because its sugar cubes resemble

the tiles of its namesake old-school game.

At its formal opening that May, the day was fair with temperatures in the low 50s. More than 1,000 guests were invited to the grand opening: “Men prominent in finance and business ... from Chicago, New England states, New York, and Pennsylvania,” The Sun reported. According to one Maryland Historical Trust document, it was hailed as “a monument of state-of-the-art modern industrial design.”

In 1922, a five-pound bag of sugar cost 26 cents and was marketed toward women who used the product at home, with one inaugural newspaper advertisement announcing, “Our doors are open—and you will be welcome—especially the Housewives of Baltimore.” Other early ads also pitched women with slogans like “Keep your man peppy with lots of sugar energy,” and “Mother is interested in quality—she selects 100% pure Domino sugar.” Over the years, the company produced cookbooks, featuring everything from recipes to dieting and etiquette tips.

It may have taken almost a hundred years, but today, a woman leads the Baltimore plant’s operations. Coricka White started as a process engineer in 2003, working her way to more senior positions in the company, before becoming Domino Sugar’s first female refinery manager last year.

On a recent day, dressed in the required safety gear from head to toe, she is purposeful in her movements but quick to flash a smile as she shares that she’s glad to be in Baltimore, having grown up in Washington, D.C. She exudes energy as she checks on ship arrivals, bounds up and down the many steps between floors of the Domino Building, and visits various departments, greeting employees by first name along the way. One of her current responsibilities is overseeing the building of four new silos, a $26-million project that will add space for an additional 14 million pounds of sugar.

✦ Coricka White stands on a

South Baltimore pier; dark brown sugar travels on a

conveyor belt; a Domino mural on Key Highway created

by local artists Greg Gannon and Frank Perrelli.

Her goal is to increase the efficiency of the refinery. “That will ensure it is here for another 100 years,” says White, 45, a mother of three who lives in Prince George’s County. She also wants to help Domino’s employees succeed.

✦ Collection of vintage sugar tins, c. 1970s; antique wooden create for cane sugar, date unknown; back of a mid-20th-century Domino recipe book.

Megan Alley, a process engineer, came to Domino Sugar five years ago with an undergraduate degree in chemical engineering from UMBC. White encouraged her to continue her education. “She really pushed and inspired me to go back for my master’s degree,” said Alley, 29, who now holds one in operations management from Loyola University Maryland.

Knowing the ins and outs of the process, Alley still finds herself amazed. “You come off the street, and you don’t know how sugar is made,” she says, noting that one of her favorite parts of the process is the centrifugal spinning that turns a yellow grainy mass into white sugar crystals. “It’s...wow!”

Her current projects focus on how to make sugar production better by improving sustainability, using less energy and water, and reducing the process’s carbon footprint, and she takes pride in being a part of Domino’s future.

“My mom loves to tell people that she has a daughter who works at Domino Sugar,” says Alley, who grew up in Catonsville. “It’s an icon for her and for my grandparents, who lived in Fells Point.”

✦ The Domino campus from the harbor.

or many Baltimoreans, the plant’s presence and the

“Domino Sugars” sign will always be a special place for

its stability and visibility in a fast-changing harbor.

Lippman started writing about the harbor landmark

long before she began photographing it, referencing

it in her 2000 novel, The Sugar House.

or many Baltimoreans, the plant’s presence and the

“Domino Sugars” sign will always be a special place for

its stability and visibility in a fast-changing harbor.

Lippman started writing about the harbor landmark

long before she began photographing it, referencing

it in her 2000 novel, The Sugar House.

“It was reassuring to go to sleep with that static neon vision blazing red in her mind’s eye,” mused her main character, Tess Monaghan. “If she were God, that was where she would make her heaven. Atop a neon sign overlooking Baltimore, guarding a mountain of sugar.”