News & Community

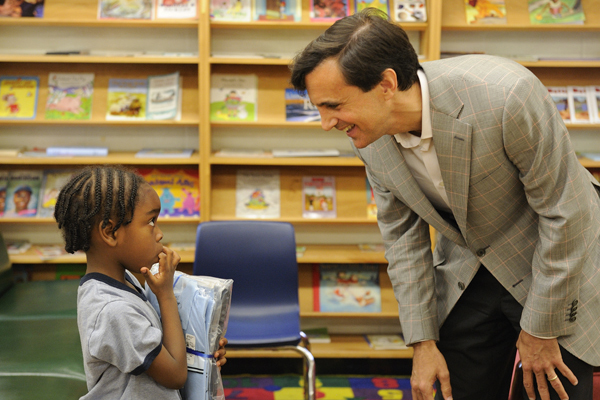

Cameo: Ron Daniels

We talk with the president of The Johns Hopkins University.

You came to Hopkins in 2009 and now your contract has been extended through 2024. That’s a long time!

The board invited me to extend my term at Johns Hopkins, and I jumped at the opportunity. My wife and I love Hopkins and Baltimore, and couldn’t be happier knowing that we will be able to spend the next eight years being part of this amazing place, including, of course, strengthening Johns Hopkins’ relationship with Baltimore.

How do you approach your role as president of such an influential institution?

People have charitably referred to Hopkins as the 800-pound gorilla in Baltimore. Just by virtue of our size, the number of employees, the number of our campuses, we’re a very important entity within Baltimore. As I’ve said on a number of occasions, the fate of the university is inextricably linked to the fate of Baltimore. For me, that’s been one of the really exciting parts of my job—just seeing the extent to which we’re able to bring the intellectual, moral, and political imagination of Johns Hopkins to bear on a number of important and interesting issues that effect the community at large. I don’t see it as a role that is beset by deep contradictions. I’ve found that there are a number of areas in which we can do well for the city and well for Hopkins simultaneously. And in fact, as we strengthen the city, we’re simultaneously strengthening Hopkins.

What would you say are your guiding principles when determining responsibility to the city?

It’s a sense that there’s a moral responsibility but also a sense that in discharging that responsibility, we have significant capabilities that we can share. A lot of the issues Baltimore grapples with— concentrated poverty, problems with access to good health care, challenges in the performances of our K-12 system, lack of green space—are issues that I think universities are uniquely poised to be able to contribute to. And then I think, it’s also having a sense of the importance of humility and modesty in how you go about bringing these strengths to the broader community, recognizing that a lot of the people who you’re hoping to be able to help have very clear views about what they need, the kinds of supports that are desirable, and the kinds of interventions that are less so.

Hopkins is such a sprawling organization—encompassing medical schools, Peabody, and the arts and sciences—there must be disciplines that you are much more familiar with than others.

My background is as a legal academic, so the one school that I know the best—I led a law school for more than a decade—we don’t have at Johns Hopkins. So, I’m in the interesting position of leading a university that actually lacks a school dedicated to my discipline. By definition that makes me a generalist, and actually that’s a great part of my job, being able to be a bit of an intellectual dilettante.

Hopkins received a $350-million gift from the school’s most famous alum, Michael Bloomberg. What has resulted from that gift?

Mike’s gift was to create 50 $5 million endowed chairs that we call the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor Program. What’s distinctive about it is that each of the professors appointed into one of these positions has his or her appointment in two or more schools of the university. The idea for it came from a simple but challenging reality for us at Hopkins, which is, we’re not a university on one contiguous campus, we’re spread across multiple campuses in Baltimore, in Washington, in Montgomery County, and then have campuses outside the United States, as well. Given that we’re geographically distributed, how could we encourage interdisciplinary collaboration? The idea was, if we can’t have geographic proximity, then we would use faculty to constitute human bridges and link different disciplines of the university together. So that program has now resulted in almost 30 appointments. It has just been so energizing to be able to engage in what has been, for the last three years, this international Star Search, where the university’s faculty has had the ability with these chairs to look out across the nation and beyond and ask the question: Who is the very best person who could tackle this issue or link these disciplines? And then recruit them to Hopkins.

Like who?

Kathy Edin is a scholar who is appointed to the Department of Sociology in the Krieger School of Arts & Sciences and also to the Bloomberg School of Public Health. We recruited her from Harvard. She recently wrote a book, $2 a Day: Living on Almost Nothing in America, which has received significant attention. Her interest is in urban poverty and the role that government can play in supporting the development of cities, in particular by looking at the least advantaged members of the community. She is playing a role in developing our 21st Century Cities Initiative. That has led to important collaborations with a program that collects data that has been supported by Bloomberg philanthropies that, in turn, has developed ties to city leadership in Baltimore and other cities.

We’ve got Kathleen Sutcliffe who was appointed to Carey Business School and to the School of Medicine. She’s someone who has an interest in the business of health care and comes from the University of Michigan’s business school. Her principle interest is in the way in which hospitals and other health care organizations organize their activities and ensure that they’re responsive to the interests of the patients. She has been a very important catalyst for work that straddles a number of different disciplines in the university but also, again, has very direct bearing on policymaking and hospital administration here at Hopkins.

You just mentioned two women and Hopkins Hospital, which just hired its first female president earlier this year. I suppose the question is why did it take so long and what does it mean now that she’s there?

Redonda Miller’s appointment as head of the Johns Hopkins Hospital was obviously a very important statement. She’s an extraordinarily talented physician and administrator and, in a lot of ways, was a very obvious choice to succeed Ron Peterson. But I think you’re right. This is a time when we’re seeing a lot of opportunities for the recruitment of new leadership and we are working hard at being very mindful of the need to think about opening avenues for underrepresented minorities and for women in positions where they previously haven’t had an opportunity to lead. And that’s something that we’re also working hard at in our standard faculty recruitment across the university, to think about how we build broad, diverse pools so that we’re reflecting the richness and the complexity of the society of which we’re a part.

The Supreme Court just upheld that institutes of higher education can use race as a determining factor in admissions. Does that change anything for Hopkins?

We were supportive of the University of Texas in the litigation and thought it was important that the Supreme Court’s prior reasoning, which saw a role for race in admissions decisions, be preserved. At Hopkins, we have experienced a truly spectacular increase in the quality of our student body over the last several years. This is measured by SAT scores, by class standing, by GPA averages, in the numbers of applications, acceptance rate, yield rate, and by attracting more students who are leaders in their schools and communities. This has also coincided with a significant increase in the percentage of underrepresented minorities in the first year class. What this affirms for me is the idea that you can have a very diverse study body while, at the same time, one need not compromise on its excellence.

You’re from Canada originally, right?

Yeah. [I’ve been in the United States] for 11 years. Just this past year, I became an American citizen. I had a green card for several years and ultimately decided that given my commitment to Hopkins and to Baltimore, I really wanted to be able to vote in national, state, and municipal elections. That, combined with the fact that I want to have the ability to get a security clearance so that I can be properly involved in the management of the Applied Physics Lab [in Laurel], which I’ve been sequestered from for the last several years because of my inability without American citizenship to get a clearance.

Wait! Let me get this straight. So there was stuff that they were working on at the Applied Physics Lab that they couldn’t tell you about because you weren’t an American?

You got it. In fact, when I came to Hopkins, the trustees had to basically do a reorganization of the Applied Physics Lab, which had previously reported into the president of the university. Instead of reporting into me, it had to report into the chair of the board of trustees who was an American citizen and was capable of getting a security clearance. So I’m on the path to become involved for the first time in this billion-dollar-plus research organization, which, for the last seven years, has been out of my line of sight.

Wow I guess they take it seriously there. That’s good to know.

There was a sense early on that maybe there’d be some way to get a clearance through some reciprocal recognition arrangement with Canada and the United States but, alas, that just had to wait until I could get American citizenship.

Now though, they can show you the really cool stuff.

They have indicated there will be a number of things that I will be interested to learn of that are happening at the lab that are deeply connected to Johns Hopkins but which I have not been exposed to.

Wow. Very euphemistically stated. I’m even more intrigued now. If they tell you where the aliens are, I want to know.

[Laughs]