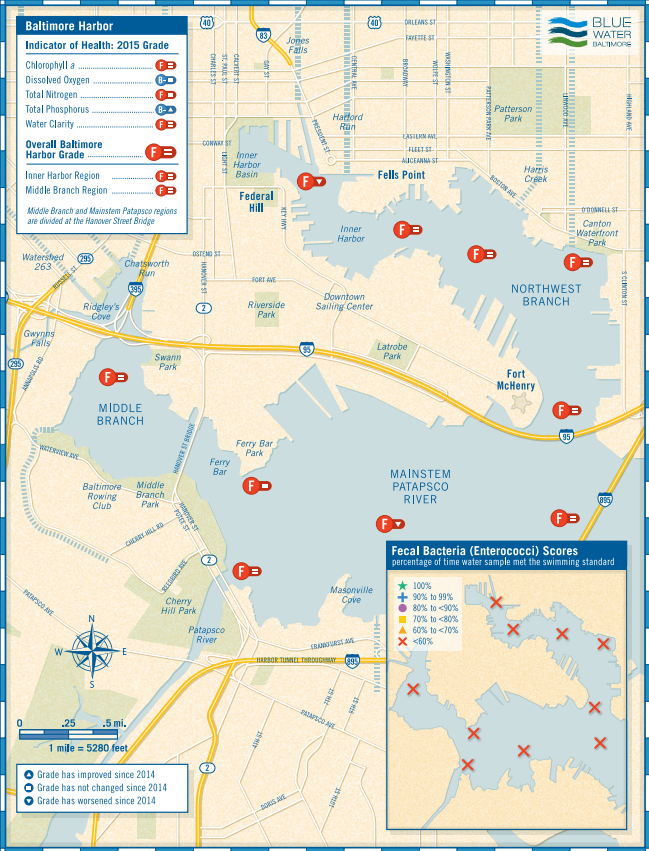

For the third straight year, the Healthy Harbor Initiative, a project of the Waterfront Partnership of Baltimore, gave the harbor an “F” in its annual water quality report card.

The more things change, the more they stay the same, could be the takeaway. But it wouldn’t quite be accurate.

First, there have been improvements. Last year, for example, the Gwynn Falls watershed was the first of the five waterways measured—the Inner Harbor and Middle Branch regions of the Baltimore Harbor, the Jones Falls watershed, and the tidal Patapsco River are the others—to receive a passing mark, albeit a D-minus. This year, the Gwynn Falls moved up to a “D.”

Also, projects like Mr. Trash Wheel, which has prevented some 420 tons of garbage and debris from entering the harbor, expanded street sweeping, the addition of 400 storm screens, and the citywide garbage can program remain relatively new efforts improving the appearance of the Inner Harbor. Nonprofit Blue Water Baltimore has been directing successful tree planting, stream restoration, and pavement reduction efforts as well.

“Now is not the time to be discouraged,” said Healthy Harbor project manager Adam Lindquist at a press conference Monday near the historic Eastern Avenue pumping station in what is now Harbor East. “We can still have a swimmable, fishable harbor by 2020.”

Lindquist also noted that while that harbor continues to struggle overall, wildlife abounds nonetheless, particularly around the city’s 70-acreMasonville Cove—a restored saltwater tidal wetland and environmental education complex. More than 130 plant and animal species have been identified at the cove, including the American eel, great blue heron, and downy woodpecker.

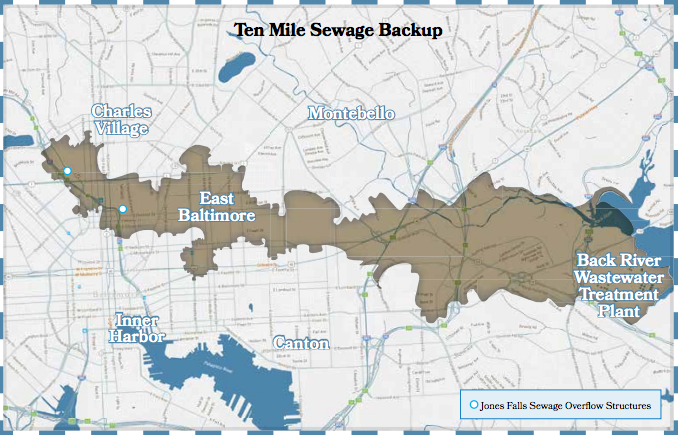

But in terms of creating a “swimmable, fishable” Baltimore Harbor by 2020—the long-stated goal the Waterfront Partnership’s Healthy Harbor Initiative—the crux remains the amount of fecal bacteria pouring into the water. That problem will continue to plague the harbor until the overhaul of the city’s century-old sewage lines are completed and a 10-mile sewage backup to the Back River treatment plant is alleviated.

The 10-mile sewage backup stretches from I-83 near Remington in the west and travels beneath sections of lower Charles Village, Station North, and East Baltimore before following Erdman Avenue from below into Eastern Baltimore County. It is caused by the misalignment of a 12-foot main pipe at the Back River site, which was discovered by computer modeling in 2010, according to Rudy Chow, who took over as head of the Department of Public Works in late 2013.

The effort to address the misalignment is expected to cost roughly $500 million, but when completed should alleviate up to 80 percent of the city’s now common sewage overflows, Chow said. He added that he fully expects that project to be completed by 2020.

“Believe it or not, we have a plan and we do have a sense of urgency to bring it into action,” Chow told a good-sized crowd of environmental activists and media gathered for the release of the report.

Baltimore City is also under a consent decree, signed with the EPA and Maryland Department of the Environment in 2002, to complete the overhaul of its sewer system—work that was supposed to be completed by Jan. 1, 2016. The city is currently renegotiating a new timetable with the EPA, Chow said, adding that he hopes to be able to talk about that “soon.”

Chow said that the “phase I” study required to meet the consent decree guidelines as well as the “phase II” design process have each been completed, and construction to repair and replace worn out lines has begun.

Also on hand for the release of the report card were Rep. John Sarbanes, state Del. Brooke Lierman, and City Council members James Kraft and Eric Costello, who represent the neighborhoods directly ringing the Inner Harbor. Lierman, in Annapolis, and Kraft, in the City Council, have both sponsored legislation in recent years to ban plastic bags.

The legislation to ban plastic bags passed the City Council, but was vetoed by Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake.

Kraft said he has hopes that the city will soon be building its first public swimming area.

“Fort Armistead Park sits just over the Key Bridge [near the Baltimore City-Anne Arundel County line where the water quality generally tests well],” Kraft said. “It’s a beautiful place to build Baltimore City’s first beach.”