News & Community

the Port of Baltimore for Sri Lanka, the ship’s captain and several crew members reached out to Andrew Middleton, the director of the Apostleship of the Sea, a Dundalk-based nonprofit which serves foreign seaman. “I didn’t know the exact time they were pushing off, but they were getting ready to sail Monday night or Tuesday morning on a 27-day voyage,” recalls Middleton. “They wanted to get off the ship, go do some shopping, and pick up whatever they might need for the next month.”

A volunteer with the organization, which is supported by the Archdiocese of Baltimore, took a handful of Dali crew members to the Arundel Mills shopping center. Middleton drove the captain and another seaman across the Francis Scott Key Bridge to Walmart and Best Buy in Glen Burnie that same Sunday afternoon.

Later that evening, the genial, 51-year-old Middleton, who lives in Dundalk with his wife, Amy, woke up at 1 a.m. and had trouble falling back asleep. Still lying in bed, he heard what initially sounded like the crash of thunder. A self-described weather nerd who regularly checks radar reports and forecasts, it struck him as odd. There were no expected storms in the area. Then, as the sound continued, he realized it was something else.

“My second thought was that a jet must be flying very low overhead, which is also strange given it’s 1:30 in the morning,” Middleton says. “The noise lasted maybe 20-25 seconds and abruptly stopped. But it is what it is, and I try to go back to sleep for a few hours.”

Finally, around 4 o’clock and still awake, Middleton started a pot of coffee. Within 30 seconds of turning on the kitchen radio, he heard that the Key Bridge—just two miles from his home—had been struck by the Dali and, shockingly, collapsed. Realizing he still had cellphone numbers for two crew members, he texted the men, both Indian, like nearly all the crew, to make sure that they, and everyone else onboard, were okay.

“We had just talked about normal stuff the day before, but I do remember asking if they were taking the Suez Canal, or if because of the stuff off the coast of Yemen and the Houthi piracy attacks, they were going around South Africa,” Middleton says. “They said they were adding a couple of days onto their voyage to take the safest route. They wanted to avoid any possible harm.”

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESLEY LAPOINTE

y 7 a.m., Middleton had done two interviews and was fielding media requests from around the country as video of the Key Bridge collapse went viral. Almost immediately, conspiracy theorists began tossing around questions about the ship’s foreign-born crew and the cause of the collision, which disappointed him. (That the U.S. Attorney for Maryland, Erek Barron, released a statement saying that terrorism wasn’t likely did not seem to matter to many. Later, a Utah state representative and others blamed “DEI.”) Middleton had worked with foreign seamen for 16 years and knew the vast majority to be professional, humble men who found the difficult work and long stretches from home to be the best way to provide for their families. His last interview went live on CNN at 10 p.m.

Meanwhile, the search for seven missing Latino workers, who had been repairing potholes on the bridge's roadway at the time of the collision, had gotten underway in the still-dark morning hours. An eighth man, a highway inspector walking the length of the bridge, had safely made it to a surviving section of bridge before the collapse of the main span. Given the height of the bridge, which rose 185 feet above the Patapsco River, and the water temperature—47 degrees—all except one were considered most likely dead by midday.

Miraculously, 37-year-old Julio Cervantes Suarez, a Mexico native who was sitting in his truck on break when the Dali struck the bridge, survived the 18-story fall. He later told NBC that the water “came up to my neck” after his well-worn pickup slammed into the river. Unable to open the vehicle’s doors, he escaped by manually rolling down a window and holding onto nearby debris for 25 minutes, until a Maryland Department of Transportation Authority police boat found and rescued him.

The bodies of his brother-in-law, Alejandro Hernandez Fuentes, a father of four, and Dorlian Ronial Castillo Cabrera, 26, were located the day after the tragic crash, submerged in 25 feet of water in a red pickup truck, near what had been the middle of the bridge.

Working in murky, extremely low-visibility conditions, divers were not able to recover the body of 38-year-old Maynor Suazo Sandoval, a married father who had raised four children and sent remittances back home to help establish a youth soccer team in his native Honduras, until the following week.

The body of Carlos Daniel Hernández, Cervantes Suarez’s 24-year-old nephew, was pulled from his submerged truck April 15. He had texted his fiancée moments before the collapse: “We just poured cement, and we’re waiting for it to dry.”

It was not until May that the body of Miguel Luna, an El Salvadoran immigrant who left behind a wife and several children, was found in a construction vehicle at the bottom of the river. He often assisted his wife with her Glen Burnie-based food truck business, Pupuseria Y Antojitos Carmencita Luna, when not working a construction shift. He picked up his dinner from his wife at the food truck before he went to the bridge that night.

“A lot of times, he gathered dinner orders from the guys he was working with and then would come by to get everything,” recalls Carmen Luna during a sometimes tearful interview at her home, with her daughter translating from Spanish. “He was very good friends with Julio, the man who survived, and also with Alejandro and his nephew. He was the best possible husband. He was hardworking. He was a family man, and we had many dreams that will not become reality. I will not forget our life together.”

The body of 37-year-old father and Guatemalan immigrant Jose Mynor Lopez, described by his pastor as “a quiet guy with a big heart,” was the last of the six men to be recovered.

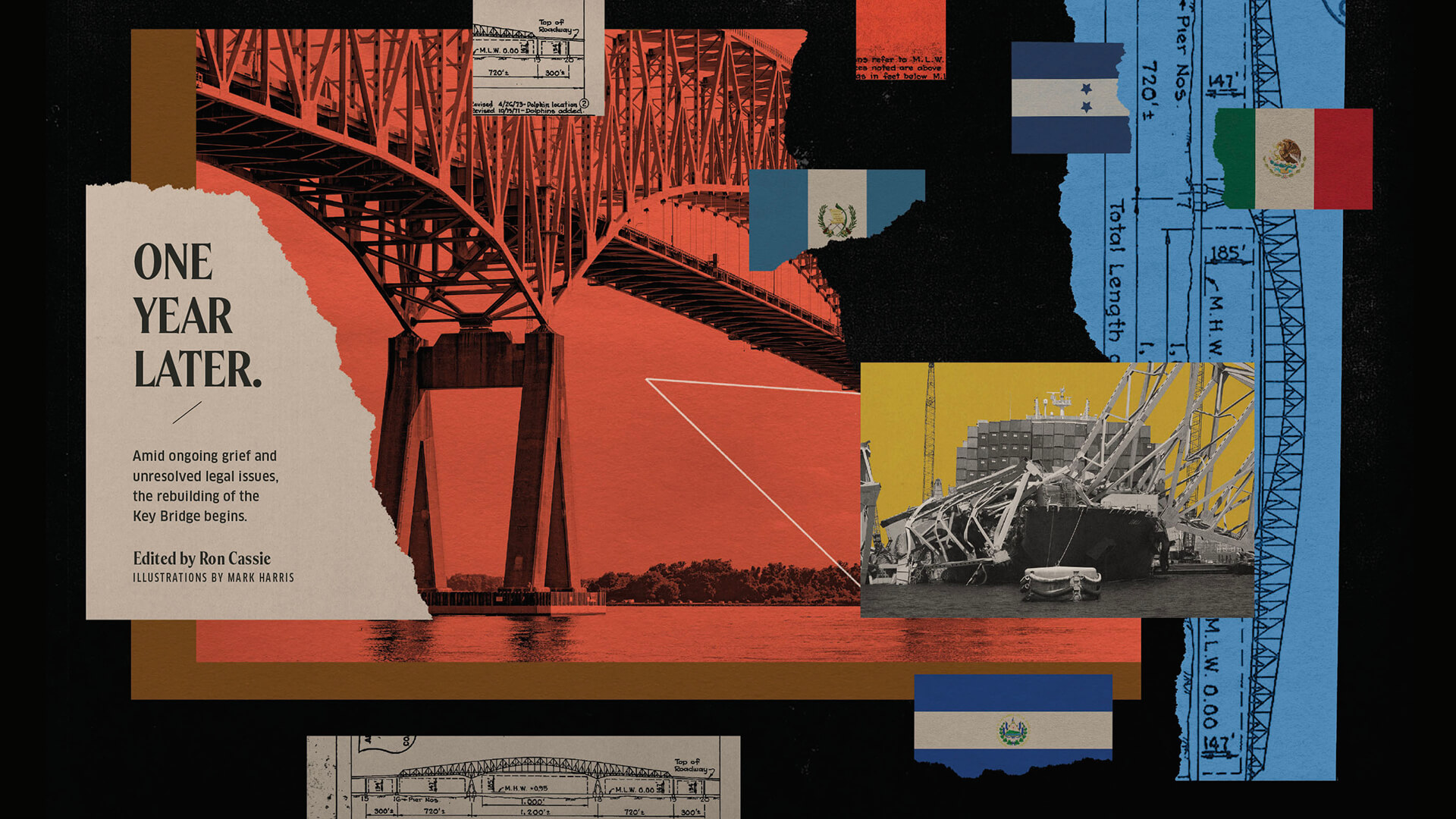

A month later, Sacred Heart of Jesus, the Catholic home of the city’s largest Latino congregation, held a vigil in honor of the six deceased victims. Afterward, Archbishop Lori William, Auxiliary Bishop Bruce Lewandowski, and Sacred Heart pastor Ako Walker led a candlelight walk through the surrounding Highlandtown community, which included crosses draped with reflective work vests, hard hats, and Mexican, El Salvadoran, Honduran, and Guatemalan flags.

From its beginning 152 years ago, when it served German immigrants, the church has been a refuge for Catholic newcomers to the U.S. and Baltimore.

After learning of the collapse from the director of the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs, Father Walker, a Trinidad and Tobago immigrant, had rushed to the scene to be with the families of lost men.

“The sadness was palpable. It was overflowing,” recalls Walker, adding that even as someone whose vocation is consoling those in grief, he had never witnessed anything like the emotion of that day. “Families were experiencing a lot of pain, hurt, uncertainty, shock. And they were trying to get answers to what had happened. What was the state of recovery? Was it possible anyone might have been alive? It was very tough for them.”

In March, the church is planning a special Mass for the victims and their families in recognition of the anniversary of the tragedy. People should continue to pray for the men, Walker says, “for their children, growing up without their fathers, wives without their husbands, mothers without their sons.

“A year might seem like a long time, if you were not directly affected—there’s distance for us in our own consciousness,” continues Walker, whose church hosted the funerals of two of the victims. “But for the families, the pain is still like it happened yesterday.”

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESLEY LAPOINTE

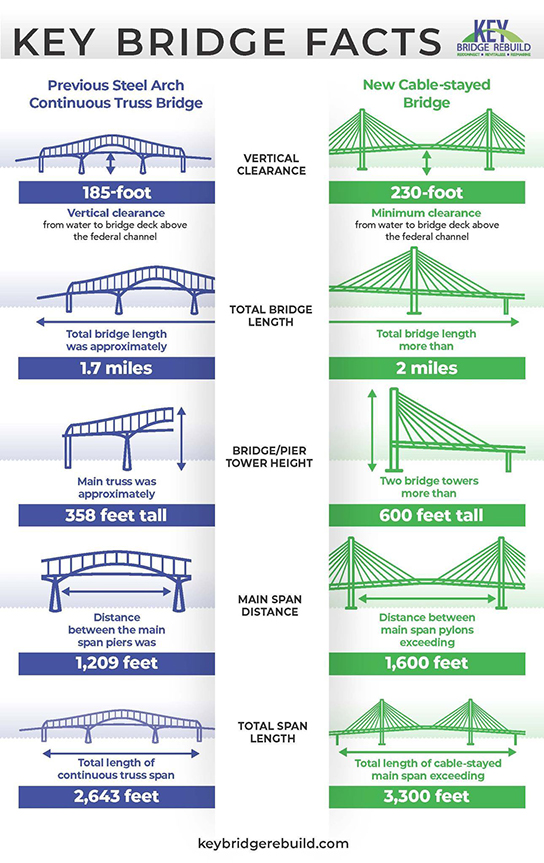

he second-longest continuous truss bridge span in the U.S. when it was built, the Francis Scott Key Bridge was a Baltimore landmark from the moment it was completed in March 1977. Two decades earlier, the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel—the pair of two-lane roads that connected southeast Baltimore and Dundalk to Fairfield and Brooklyn— became the first way to cross the Patapsco River. But with the populations of Baltimore and Anne Arundel counties ballooning by some 250 percent, a second crossing was needed. And the Key Bridge—so named because of its proximity to the spot where its namesake penned “The Star-Spangled Banner”—was notable for another reason. It was the final piece of the Baltimore Beltway.

But its construction was not without controversy. The Maryland General Assembly and then-Speaker of the House Marvin Mandel wanted to build another tunnel. Gov. Spiro Agnew wanted a bridge. In back-and-forth debates, the “Outer Harbor Crossing” developed into a political football and then a flashpoint for corruption, which in hindsight is not a huge surprise considering the players involved. (A tunnel would have avoided potential conflict with the port’s shipping traffic, but Mandel came around to Agnew’s less-expensive bridge proposal after he became governor.)

Agnew, of course, was chosen by Richard Nixon to be his running mate in 1968. But not before his administration authorized $220 million in bonds to cover the cost of a second Bay Bridge—and a second crossing across the harbor. Agnew awarded the Key Bridge design contract to a politically connected Baltimore firm, Griener Engineering, which eventully became part of the kickback scandal that helped end Agnew’s vice presidency in late 1973.

Two other companies would reorganize and change their names due to scrutiny around their Key Bridge contracts and links to Mandel, who became governor when Agnew departed for D.C. Three months after the Key Bridge opened, Mandel stepped down from office because of his own horse racing-track scandal.

It’s worth noting the Dali was not the first vessel to strike the Key Bridge. In 1980, the bridge was struck by a significantly smaller container vessel. However, it required relatively minor repairs from the blow to a “fender” on one of its main supports, and only briefly led to discussions about strengthening the bridge’s structural protections.

In the end, the political backstory—which included a successful fight by Locust Point residents to prevent placement of the bridge near Fort McHenry—was quickly forgotten.

Long and narrow, a mile and a half long and 1,200 feet across its arching main span, its functionality and simple grace stood as a monument to the ironworkers who built it and the port’s industrial might.

“Immediately, the bridge shows up in all kinds of public ways and popular references,” says Mike Kuethe of the Baltimore Museum of Industry, who researched the history of the bridge for a public presentation in January. “Companies begin advertising they’re only five minutes from the Key Bridge. Real estate companies advertise that houses or condos have views of the bridge. The Baltimore Sun ran a regular outdoors column, and you start seeing references to the best fishing spots inside of the Key Bridge or the distance of certain fishing from the Key Bridge.

“There are comments, too, from people able to look down on Curtis Bay and Dundalk from the bridge, getting a view that previously you could only see by helicopter or plane,” Kuethe adds. “It gives Baltimoreans a different perspective of the outskirts of the city.”

As fans of The Wire will recall, the Key Bridge also served as a poignant backdrop in the show’s second season, when longshoreman union leader Frank Sobotka and his stevedore nephew briefly share a ruminative lookout across the harbor and bridge as seagulls glide past and water laps against the shoreline.

“Great view,” says the nephew.

To which his uncle replies: “It’s fucking picturesque, is what it is.”

Above: Carmen Luna, whose husband Miguel

Luna was killed in the Key Bridge collapse,

speaks beside a memorial photo of her

husband at a press conference.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESLEY LAPOINTE

n the early hours of March 26, Maryland Transportation Authority dispatchers were informed of a threat to the Key Bridge about a minute and half before the 947-foot Dali struck one of the bridge’s main pillars, causing the center span to collapse. Onboard were 21 crew members, two local pilots, and 4,680 20-foot equivalent containers.

Just before 1:25 a.m., when it was roughly three ship lengths out from the bridge, one of the Dali primary electrical breakers tripped. It caused the loss of electric power to the shipboard lighting and most of its equipment, including the main engine cooling and steering gear pumps, which automatically shut down the 112,000-ton vessel’s diesel-powered propellers.

The crew manually closed the open breaker, restoring power, but only briefly. At 1:27, at the same moment the senior pilot ordered the anchor dropped, the Dali lost power a second time, now little more than a football field from the bridge.

Drifting at 6.5 knots, the starboard bow struck pier No. 17 of the bridge at 1:29 a.m. A Dali crew member told National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigators that, as he was releasing the brake on the port anchor, he was forced to flee the bow to escape falling debris. As the bridge deck collapsed onto the ship’s bow, another crew member, also trying to avoid falling debris, sustained a mild injury.

By 1:34 a.m., the Coast Guard issued an urgent request for assistance from passing ship traffic. The first Coast Guard boats arrived at 1:51 a.m. Multiple agencies immediately began searching for survivors from the road maintenance crew, only halting the active search that evening. Their efforts transitioned to recovery operations the next day.

It would take 11 weeks for the bridge debris to be cleared, temporarily stranding some 40 ships in the Baltimore harbor, and largely shuttering commercial operation at the port. Some 15,300 jobs were directly impacted by the bridge collapse and the port’s closure, with 140,000 jobs indirectly affected. The nation’s largest terminal for auto exports, Baltimore shipped nearly 850,000 cars and light trucks in 2023. It is also the second-largest U.S. hub for coal exports.

According to a preliminary NTSB report, a loose cable likely caused Dali’s electrical issues. When disconnected, the problematic cable triggered an outrage similar to what occurred prior to striking the bridge.

Later, as media attention dissipated that summer following the reopening of the channel, the mouth of the Patapsco River took on a surreal quality—a void in the skyline—with its missing span and 30,000 displaced daily commuters.

Kayaker Matt Klinck paddled to the bridge remains this past December, taking a video camera with him to document the scene before reconstruction began. Up close, the gap between the two sides of the bridge was shocking. “Once you see the first half of the bridge, you think, ‘Where’s the other half?’ and you keep paddling, paddling, and paddling, and finally, you’re like, ‘Okay, there’s the other half, jeez.’

“It was also very quiet,” continues Klinck, who posted a video of his trek on YouTube, where it quickly received more than 2,000 views. “When I paddled the Bay Bridge, you constantly hear car noise, but when you paddle near the Key Bridge now, there’s no car noise. There’s an eeriness similar to those pictures of New York City when the streets were empty during the pandemic. The silence is stunning.”

The other striking takeaway for Klinck was the iron rebar bundles—which once fortified the bridge pillars, but were now twisted and bent by the seismic collision—and drooped over what was left of the cement base. “From their shape, they looked like they were made of string, not steel,” he says. “Hanging loose like threads of clothing.”

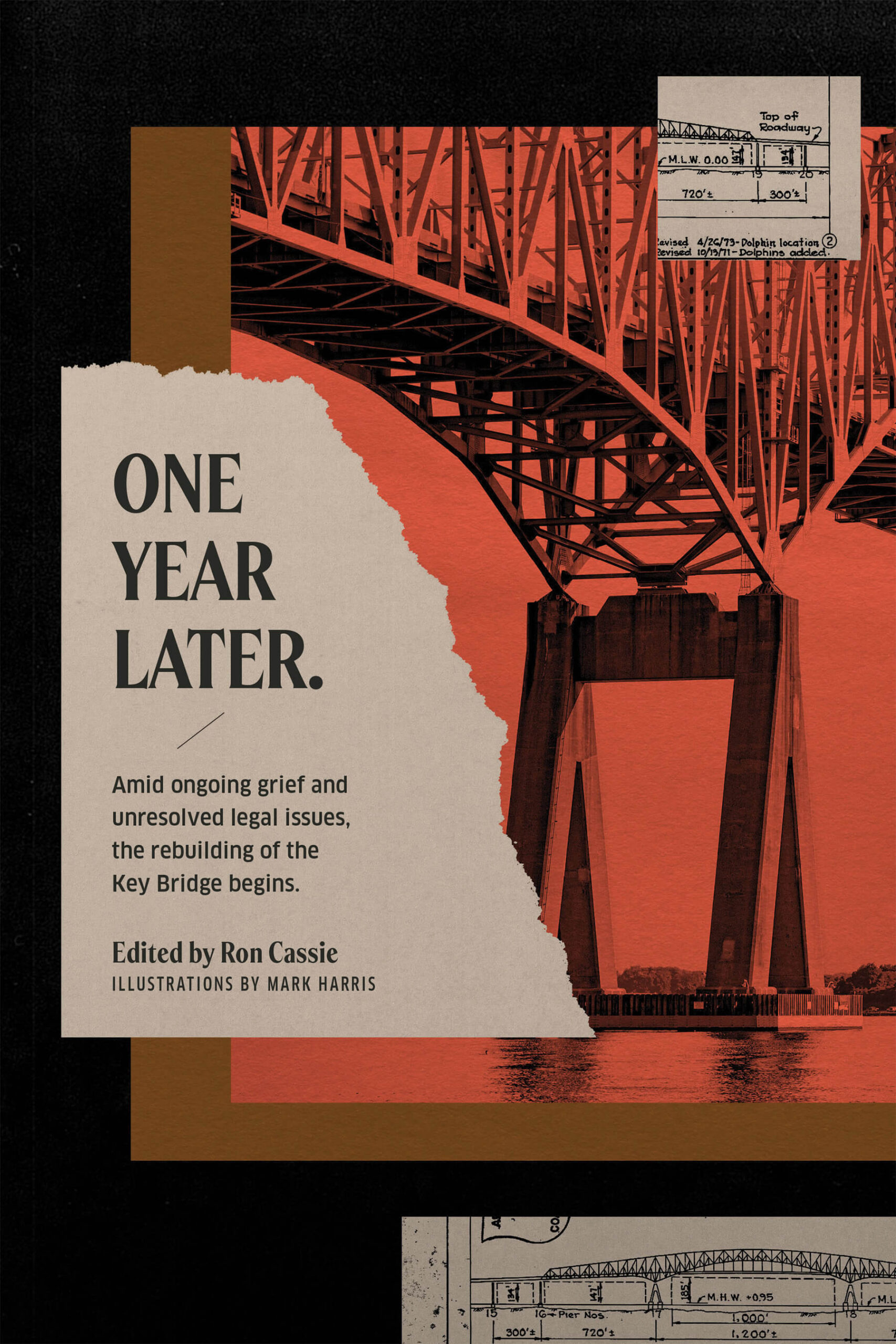

Preliminary designs

for the new bridge.—COURTESY OF MARYLAND TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY

ive days before Christmas, former President Joe Biden signed a bill that averted a government shutdown and included a pledge to fully fund the rebuilding of the Key Bridge. Afterward, Gov. Wes Moore declared that “while the tragic collapse of the Key Bridge happened during our time in office, we will rebuild it on our watch.”

Much has changed, however. Whether President Trump attempts to retroactively cut off the legislated funding, which cannot be done legally by executive order, remains to be seen. For now, the work is a go and the projected completion date is October 2028.

The preliminary designs for Key Bridge, revealed in early February during a press conference at Tradepoint Atlantic in Sparrows Point, are conceptual and part of what’s referred to as a progressive design build.

That said, the new bridge will be four lanes wide, the same as the original, but will be significantly higher—a projected 230 feet above the river at its highest point—to make room for increasingly large container vessels. The new bridge will also be the first cable-stayed in Maryland, in contrast to the truss style of the original bridge, and it will have a wider channel opening as well as an enhanced pier protection system.

No decision has been made yet on whether the new bridge will carry the same name.

Nor has there been a decision about the construction of a permanent memorial to the victims of the tragic collapse, as some have called for.

An unofficial, evolving memorial for the six victims at Hawkins Point—including flowers, candles, crosses, murals created by Texas-based artist Roberto Marquez, and Mexican, Guatemalan, El Salvadoran, Honduran, and American flags—was vandalized in early June.

Maria Aldana at the

Baltimore Museum

of Industry conducts

interviews.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

Maria Aldana, the director of the nonprofit Art of Solidarity, has been recording oral and video histories of impacted community members, including the victims' families, for the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Aldana says that, like many members of the Baltimore-area Latino community, she sees herself and her family in those who lost loved ones a year ago.

“The kind of relationships that I saw among the victims’ families were very similar to the relationships I have with my own parents, my brothers, my aunts, my cousins,” Aldana says. “I met family members arriving from Mexico. I watched the daughters of one of the victims, both teenagers, console each other, their younger sibling, and their mother.

“And seeing Carmen Luna be there for her children, grandchildren, putting herself last, there are no words.”

—Ron Cassie

COMMUNITY OUTREACH

In the shadow of the Key Bridge, the historically Black community of Turner Station finds hope for the future.

By Lydia Woolever

WHEN THE Francis Scott Key Bridge collapsed last year, less than 500 feet from Turner Station’s Mt. Olive Baptist Church,Pastor Rashad Singletary knew what to do. Using his experience as head of community affairs for the Mayor’s Office and a longtime Safe Streets director, he quickly organized a community vigil for that very evening, providing a moment of unity amidst chaos and fear.

“We know this was a tragedy—individuals lost, families impacted, communities impacted,” says the 36-year-old Singletary, whose historically isolated Black community sits at the tip of Dundalk on the Patapsco River. For nearly a half-century, the bridge served as a lifeline to family, jobs, resources, amenities, and the outside world. “But faith also says it’s an opportunity, for us to see what God is going to do through us.”

In Turner Station, churches have long been more than just Sunday service. St. Matthew United Methodist provides a weekly food pantry. New Shiloh Baptist offers music lessons. Union Baptist hosts annual Black History Month celebrations. First Apostolic Faith Gospel Tabernacle throws back-to-school giveaways. Over the years, they’ve also teamed up with politicians and community leaders to confront persistent concerns, which include the local food desert, environmental hazards like pollution and flooding, and affordable and improved housing as developers eye up the neighborhood’s waterfront property.

Now, since the collapse, faith leaders feel a newfound urgency, as their congregants worry about what the future might bring. And a sense of camaraderie, too. “It’s always out of the collective that we can do greater things,” says Pastor Kay Albury of St. Matthew. “Each church has its own strengths, so . . . we can share resources and empower each other.”

Last year, Singletary gathered his colleagues for an introductory meeting with the Maryland Transportation Authority Police, and he has since joined the port’s Tradepoint Atlantic board as a community liaison. Following in the footsteps of St. Matthew, which hopes to transform its parsonage into a crisis center for concerns like mental health and homelessness, Mt. Olive is also now applying to become a nonprofit community development corporation, with the goal of obtaining funding to launch additional services such as financial literacy programming and an early learning development center.

“Building infrastructure is our main focus,” says Singletary. “Turner Station is a resilient community. But how do we capitalize on this moment to make sure that, as billions of dollars are being allocated to rebuild the bridge, we’re also bringing resources into this forgotten community that are going to be sustainable for generations to come.”

In the early 20th century, Turner Station grew out of the industrial heyday of the two World Wars. During the height of segregation, African-American workers had to find their own housing, and built a vibrant community with schools, businesses, and, of course, churches.

“We were a self-sufficient community,” says Pastor Donald Jones of Friendship Baptist, who grew up on Fleming Drive in the 1950s. Eventually, as factories declined, so too did populations and services, with residents remaining underserved for decades. “But we hold onto hope. One of my favorite scriptures is Jeremiah 29:11, where the Lord says, ‘I know the plans I have for you . . . to give you hope, and a future.’”

On March 26, one year after the collapse, the community will once again return to the pews of Mt. Olive, this time for a day of remembrance—of the lives lost, of the old bridge, of dreams for the days ahead when a new one is built.

“When you come into the community, you could always see that arch,” says Jones. “Almost like a reminder that Turner Station is still there.”

THE WIFE OF A KEY BRIDGE VICTIM HOLDING A FLOWER. —PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESLEY LAPOINTE

ORAL HISTORY

Mayra Loera is the program manager for client services at the Esperanza Center, which has served the Baltimore immigrant community since 1963. A Mexican immigrant, Loera shares her memory of the Key Bridge collapse and the Esperanza Center’s assistance to the families of the six immigrant workers who died in the tragic event.

Interview by Maria Aldana / Edited by Ron Cassie

used to travel over the Key Bridge two or three times a week. I always prepared my phone, when it was evening, to take a picture of the sunset because it looked so beautiful with the bridge. I still have some of those pictures in my phone.

My boyfriend [who lives near the bridge] texted me at five in the morning [the day of the collapse]. I was visiting my sister in New Jersey. All I saw was the bridge is gone. I was like, “Am I reading this right? What is he talking about?” And then he sent me a video and I got up and made a cup of coffee and I just sat there, and I watched the video over and over again.

It was scary because I crossed that bridge on my way to New Jersey from [my home in Anne Arundel County]. And then I realized that I’m not going to cross that bridge on the way back home. I also got an email from my supervisor that we were going to be involved in helping.

At [Esperanza], we see a lot of victims of crime, a lot of people who are escaping a situation in their home country that really leaves them no choice but to seek a better life somewhere. I’ve been asked why don’t undocumented people just do it the right way? Take a plane, send your papers, and come in and work. Every single person wishes they could do that. The problem is the system doesn’t really work for people with these needs, and they live in poverty. If you can provide the things that they request, it may take five, 10 years for someone to be approved. I’ve talked to families that experienced trauma on the way here. Some feel so sad and desperate that they just want to go back home. [The immigrant community] experiences discrimination at work. People walk through our doors saying, “I’ve worked for a month and my boss kept saying, ‘I’ll pay you later.’” And they never saw the money.

[After the collapse], we met weekly with Catalina Rodriguez Lima, the director of the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, and Giuliana Valencia-Banks, chief of Immigrant Affairs for Baltimore County, and other crisis response groups, sharing information and [figuring out] the best way to provide services to the impacted families.

The Esperanza team visited with the victims’ families and filled out financial assistance applications so that they wouldn’t have to worry about not working during this terrible thing because they don’t have money to pay rent, don’t have money for food or their car payment. We talked almost every day and sometimes multiple times a day with families when [first responders] were still searching for their loved ones. Maryland Casa, their legal team, made sure that family members obtained visas to travel to the U.S. to be with their loved ones. They worked day and night, seven days a week.

We told them we’re going to buy you a plane ticket so that you can come to the U.S. and if they needed a hotel, that too. We sort of became a travel agency. Some of them had never traveled before. They sometimes called that they were lost in the airport and then they find nice people that guided them to where they needed to go so that they wouldn’t miss their plane.

THE HAWKINS POINT MEMORIAL HONORING THE SIX MEN WHO DIED IN THE KEY BRIDGE COLLAPSE, INCLUDING MURALS BY TEXAS-BASED ROBERTO MARQUEZ. —AP PHOTO/MARK SCHIEFELBEIN

ORAL HISTORY

Guiliana Valencia-Banks, a native of Peru, joined Baltimore County as its first immigrant affairs outreach coordinator in 2021. Now the chief of Immigrant Affairs, she led the county’s effort to assist the families impacted by the collapse of the Key Bridge.

—Interview by Maria Aldana / Edited by Ron Cassie

woke up that morning [of the Key Bridge collapse] with plans of going to an education conference in Montgomery County. I saw the text messages and I thought, “Okay, well, I’m supposed to be at this this conference.” I got dressed, drove down to Montgomery County, and then the reports started to come in about a work crew on the bridge. I parked my car at Montgomery County Community College, told the organizer that I was not going to be staying, and turned around and drove back to Baltimore.

I went to where the first responders and county and city officials were [situated] and spoke to our chief of emergency management and asked if I could check in on the families. Once we knew there was a work crew on the bridge, [and understanding] the demographic of folks that work in construction, I instinctively knew there were at least one or two immigrant families who were going to be impacted by the collapse of the bridge.

At 10:30 a.m., we didn’t know whether it was going to be a recovery mission versus a rescue mission and there was still the hope that we were going to find survivors. I wanted to ensure that the immediate family and extended family members were getting services through an interpreter and that there was mental health support for the families while they waited for the news.

As an immigrant, I know the first thing you must do is address [the language barrier]. My mom has lived in this country for 36, 37 years. She speaks enough English to have passed the civics test and naturalize, and she can go to the bank and ask questions about the status of her bank account, and she can go to the grocery store and read the signs and know where to find the pasta. But if she’s going to have a conversation about her blood pressure or her diabetes, she’s not having that conversation in English.

Also, having gone through the process of applying for asylum and naturalizing and seeing how that process works . . . my lived experience shapes the way I react to my work, which has always revolved around providing services to immigrants. The entire time I was also in communication with Catalina Rodriguez-Lima from the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs, just texting back and forth about what we were seeing and what were some of the needs that we were going to have to figure out solutions for.

[Ultimately], we were able to get the two largest direct service providers of immigrant services to work together, three jurisdictions to work together, and the state and the federal government. We had 34 humanitarian paroles [visas] approved for family members [of the deceased workers] and that happened in weeks, whereas that normally takes months, if not years. That’s because we were collaborating with our U.S. senators’ offices, the White House, and the nonprofits.

At the end of the day, we have to remember that these are people. They’re not just construction workers or, you know, immigrants. These are human beings, and they live in our communities, and they have children in our schools, and they have family members that are grieving and experiencing this [collapse of the Key Bridge] on a much deeper level. I don’t drive over bridges in the same way that I used to before March 26, and I didn’t lose my dad.

CRISIS AND THE LAW

Passed in 1851, the federal Limitation of Liability Act (LOLA) was intended to shield vessel owners from significant financial liability due to events beyond their control, such as storms and shipwrecks.

By Kate Livie

THE LOOPING video footage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge disaster on the morning of March 26, 2024 showed what appeared to be a straightforward tragedy: a massive ship, adrift without power, colliding with the base of one of Baltimore’s iconic landmarks.

However, the ensuing investigation and legal battles against the Dali’s owners and operators have exposed complicated questions about a controversial, some might say antiquated, 19th-century maritime limited liability law.

Built in 2015 in South Korea, the Dali, which went back to sea earlier this year after extensive repairs, open water trials, and recertification, was a titan designed for the demands of modern global shipping. Owned by Grace Ocean Private Limited and operated by Synergy Marine Group, the ship was registered in Singapore, which is known for strict regulatory oversight. But despite its advanced technology and compliance on paper, the Dali’s collision revealed significant gaps in its operations and maintenance.

The disaster unfolded during what should have been a routine departure. At 12:40 a.m., the Dali left the Port of Baltimore carrying over 4,600 containers, guided by two pilots and assisted by tugboats. Investigations later brought to light a domino-effect of systemic failures onboard Dali. There were long-documented vibration issues that damaged equipment, making it vulnerable to power outages, and an over-reliance by the crew on its flushing pumps, which violated safety protocols and rendered generator restarts impossible during blackouts. And it suffered a power outage just 10 hours before departure that had not been reported to the U.S. Coast Guard or the two pilots prior to departure.

Not only did these lapses create a potential case for negligence against Grace Ocean and Synergy Marine, but the legal fallout brought renewed attention to an arcane bit of maritime law. Passed in 1851, the federal Limitation of Liability Act (LOLA) was intended to shield vessel owners from significant financial liability due to events beyond their control, which in the wooden ship era of the mid-19th century largely meant storms and shipwrecks. Under LOLA, Grace Ocean and Synergy Marine sought to cap their liability at $43.7 million—essentially the combined value of the vessel and its pending freight.

In the Dali’s case, however, additional possible damages included the estimated $1.7-billion cost of rebuilding the Key Bridge, economic losses from months of halted port traffic, and, of course, the devastating human toll. Civil wrongful death claims by the families of the road workers who died in the crash are among the nearly four-dozen lawsuits that likely will remain unresolved until 2026.

At the time of its passage by Congress, LOLA was put forth to incentivize maritime commerce in an era when commercial vessels were small and slow, voyages were risky, and overseas communication could take weeks or months. Contemporary critics argue that the modern shipping industry, with its satellite communication, robust safety protocols, and enormous vessels, no longer needs such protections to do business.

In a recent maritime law panel on the Dali disaster at the Maryland Center for History and Culture, James Jeffcoat, a member of the MCHC maritime committee and a partner at Whiteford, Taylor & Preston, summarized the argument against LOLA. Eliminating the limits on the shipping industry’s liability, Jeffcoat said, “can discourage risktaking and compensate those injured as a consequence of someone else’s negligence.”

Despite its critics, the 164-year-old law has its defenders, mostly in the shipping trade, not surprisingly. They argue that maritime shipping is the backbone of global trade, carrying over 80 percent of goods worldwide. Removing these liability protections could deter investment, LOLA proponents argue, raising shipping costs and disrupting an economy that has benefited from these safeguards for more than a century.

The Singapore-flagged Dali container

ship after its March 26, 2024 collision with

the Francis Scott Key Bridge.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY WESLEY LAPOINTE

Meanwhile, the legal consequences for the Dali’s owners and operators have already begun. In late October, Grace Ocean and Synergy Marine agreed to pay $102 million to the Justice Department to cover federal cleanup costs, including removing 50,000 tons of debris from the river. Additional lawsuits, including claims by Maryland, Baltimore City, and Baltimore County for expenses related to the cleanup and rebuilding of the Key Bridge—as well as the aforementioned claims by local businesses, the victims’ families, and the longshoreman’s union for their economic losses—will likely push total damages much higher.

“Now that the federal government has committed to cover the cost of replacing the Francis Scott Key Bridge,” says Jeffcoat, who is closely following the outcome for Maryland’s claim, “one of the most interesting aspects of the ongoing litigation will be to see to what extent Maryland will succeed in recovering these costs from the Dali and her owners to reimburse the federal government for the cost to rebuild.”

As the courts untangle the liability issues, the maritime community faces a reckoning. Will the Dali disaster lead to meaningful changes in how ships are managed and how justice is served in maritime law? Or will it become another cautionary tale, overshadowed by the next tragedy?

For now, the legacy of the Dali is one of loss, questions of accountability, and the urgent need to reconcile 19th-century laws with 21st-century realities.

Retired Local 16 Ironworker Frank Piccione with a photo of his Key Bridge crew.—Photography by J.M. Giordano

WORKING HISTORY

Frank Piccione was raised in Gardenville and did three tours in Vietnam before coming home and joining Local 16 as an apprentice ironworker. He’s 78 today and lives in Rosedale.

worked in the field as an ironworker for 25 years. But I was with the Ironworkers Local, and then the International Association, for 45 years altogether, holding a lot of different positions. Former Gov. [Parris] Glendening appointed me to the Maryland Apprenticeship and Training Council. I was president of the Baltimore Building Trades Training Council. I retired in 2013.

My father was a United Autoworker at the GM plant on Broening Highway. I’ll tell you a quick story. When I got back from Vietnam in 1969, I was going around visiting family and so one day my cousin Pete invites me in and I sit down at his dining room table. I couldn’t help but notice there’s a centerpiece on the table, and in that centerpiece was his paycheck from the previous week. It was for $200 and some dollars, $240 maybe, something like that. I said, “What the hell do you do?” And he said, “I’m an ironworker.” And I told him, “If you’re making that kind of money, you’ve got to tell me where to go.” That’s how I got into hard work.

The apprenticeship was three years. Now it’s four, as it is with most trades across the United States. It’s not just about climbing iron or tying rebar [the process of connecting reinforcing steel bars with metal wire to create a strong structure]. Ironworkers work in nuclear facilities. It’s many hours of safety and health training before you can step foot on a job site. And when we use the word iron, we’re really talking about structural iron, steel, precast concrete, and today, glass and other composite materials.

Two stages of the Francis Scott Key Bridge under construction in the mid-1970s. Cars and trucks approach the FSK toll

plaza before heading over the iconic truss bridge.

—COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

Before the Key Bridge, I worked on the second span of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, and after I finished there, I actually worked on a renovation, a retrofitting, of the first Bay Bridge. A lot of guys didn’t like to work rebar because it was what we called “grunt and groan” work. Have you ever seen a guy tying rebar? Another term we used to describe it was “assholes and elbows” because you’re bent over all the time and all anybody sees is your asshole and elbows. But that work as a young guy prepared me for other phases of the trade. Whenever work came up, I always worked. Some guys would turn away from the grunt stuff. Hell no, the money wasn’t dirty.

There was one man who was killed working on the Key Bridge, on land, on one of the approaches to the bridge. He was inside a concrete rebar column, and I don’t know if a gust of wind came up or whatever, but that column went over, and he was crushed—the only fatality that I’m aware of. After the Key Bridge, the Brandon Shores power plant [built in the early 1980s in Anne Arundel County] was another large project.

There was definitely a lot of pride in building the Key Bridge. To me, it wasn’t about the port—it was that it completed the Beltway and it eased traffic. Later, my last 12 years when I was with the Ironworkers International, I commuted to D.C. over the bridge. I guess I’m lucky I don’t have to do that anymore, but when it came down, that was heartbreaking. They’re talking about the new bridge won’t be done until 2028. Right now, my health isn’t bad, but that’s years from now, if you catch my drift. I hope to see it.

I still have a photo of our raising gang, [Piccione holds it, framed, in his portait, above], that closed the truss. Keep in mind that truss, the big arch, was what held the roadway. We set the final piece.

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

WORKING HISTORY

Buddy Cefalu grew up in Pimlico and after returning from military service in Vietnam, he joined Ironworkers Local 16 and helped build the Key Bridge. Now, 76, he lives near Ocean City.

y father was in the produce business, which had our family name on it. My grandfather Giovanni and great-uncle Phil started the business at the old Belair Market after they came from Cefalù, Sicily, in the early 1900s. I went to Saint Ambrose School on Park Heights Avenue and then Towson Catholic High School. I went into service in 1966 and served four years, including two tours and 18 months in Vietnam.

The day I came home, my mom and dad had a “welcome home” get-together for me at the house, and my brother-in-law Jerry said, “What are you going do now, boy? You can’t do that shit you were doing over there.” I told him that I didn’t know, but the first thing I was going to do was go to Wildwood for two weeks and chill out.

My brother-in-law was an ironworker in Local 16 and he helped me to get into the local’s apprenticeship program. That’s where my career began, in the summer of 1969. Frank Piccione (whose oral history is above) was in the same three-year apprenticeship class.

How do I say this? Like in everything else in life, everyone is not the same. Just because you have the title of an ironworker, doesn’t mean that you’re going be the guy up on the top of the building or bridge raising the steel. I worked as Frank did and Butch did (below), mostly in the erection of steel on buildings and bridges—numerous buildings in downtown Baltimore and in the surrounding counties, Baltimore, Howard, and on the Western Shore. We never did too much on the Eastern Shore other than the second span of the Bay Bridge.

We were still fairly young but experienced ironworkers when the Key Bridge project started. The Key Bridge was a chance for young guys starting in the business to make their bones and build a reputation. You live on your reputation, and nobody wants a bad reputation, meaning you couldn’t or wouldn’t do the work—you didn’t have the confidence, or you weren’t reliable. It was physically demanding and a prideful thing to help build that thing with your own two hands. I’ve had four back surgeries and I’m going back to Hopkins for a fifth, a spinal fusion, a byproduct of all those years.

I don’t remember the first time that I drove over the Key Bridge, but I made thousands of trips over it, especially after I became a union business agent. Our union hall was so close to it. We’d use that as a main thoroughfare from Dundalk to the Curtis Bay side. It made everything so much more accessible.

As far as memories, the tall ships sailing beneath the bridge to the Inner Harbor [in 1976] just as the bridge was getting to the point where we were setting the roadbed—that was like a movie from our vantage point. But there are a lot of memories. The bitter cold in the winter, the brutal heat and humidity in the summer. We fought conditions like windy days. We went out and worked even if it was 18 degrees because the next day it might sleet and be ice. You make each day count. That’s what ironworkers do. That’s how it got built.

It was the second-longest truss bridge in the world when it was built, just the site of the arch was a symbol of industrial strength. It was a monument to the working-class people of the area, the last vestige of an era when generations worked at Bethlehem Steel, General Motors, and Lever Brothers. I just hope I live long enough to see it rebuilt and the first car go across.

—PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

WORKING HISTORY

Butch Henry grew up in O’Donnell Heights. He served in Korea before coming home in 1965 and eventually joining Ironworkers Local 16 and helping build the Key Bridge. Now 80, he lives in Colgate.

got my GED in the Army, but I didn’t have a plan when I got out. I first started working at a drug company, but when I lost that job, my uncle got me an apprenticeship with Local 16. My father and two of my uncles were ironworkers. I was on the second span of the Bay Bridge and loved the work. Everything it was. I was young and working with a lot of other young guys. In those days, if you didn’t like a certain job that you were on or got tired of it, you could go to the union hall and get another.

In the late 1970s, I worked on the USF&G Building (the first Inner Harbor high-rise when built at 100 Light Street). There was even a photo of me working on that building in Baltimore magazine. Not everybody is built to work in an office, but I did do that my last couple of years, as a business agent with the ironworkers, before retiring.

I spent two-plus years working on the Key Bridge. I was married by then with three kids in Middle River. We worked 10-hour days, seven days a week, to stay on schedule.

I was 200 feet up [one day] when a bolt got sheared off a beam. I don’t know if a wave came by, but something caused the crane to move as we were fastening the beam and it hit me in the mouth. Four of us were up there and I started to fall forward. The guys grabbed me. A friend found my teeth 20 feet down in the section below. I walked off the bridge myself and returned the next week still missing my front teeth.

I do remember the ironworker on the other derrick who fell off the bridge and got paralyzed. I was there that day. We stopped working until he was lifted out and then we went back to work because management told us no knocking off. The guys in the union donated money to his family. I had another serious injury working a section of I-83 near the old Pepsi sign 12 to 15 years afterward. I fell 40 feet when a section of rebuilt road collapsed and broke my ankle.

Later, I took a job with the state, doing road maintenance on the Key Bridge like those poor guys who died.

I wake up every day at 6 a.m. and watch Morning Joe and the first image I saw after turning on the television [the day of the tragic crash] was the bridge collapsing. It brought tears to my eyes. The guys up there that night that lost their lives—my heart broke on that. I couldn’t believe that would ever happen.

Every time we that we’d drive over the bridge, I tell my grandkids that I helped build it. I don’t know if the average person understands how dangerous that work can be or not, to tell you the truth. I had a friend who was a cop and lived in our neighborhood. He said he wouldn’t do that kind of work. But I wouldn’t be a policeman, you know? I guess he understood what it was all about.

To me, it doesn’t matter if the new bridge is named the Francis Scott Key Bridge or if the design is similar in some way—as long as it’s safer. I mean, I thought that bridge was safe. We would talk about that—that the bridge would never come down. And then a damn ship as big as that [nearly 1,000-feet long, weighing more than 100,000 tons] knocked it off its haunches. That was shocking. You thought it was impossible.