Business & Development

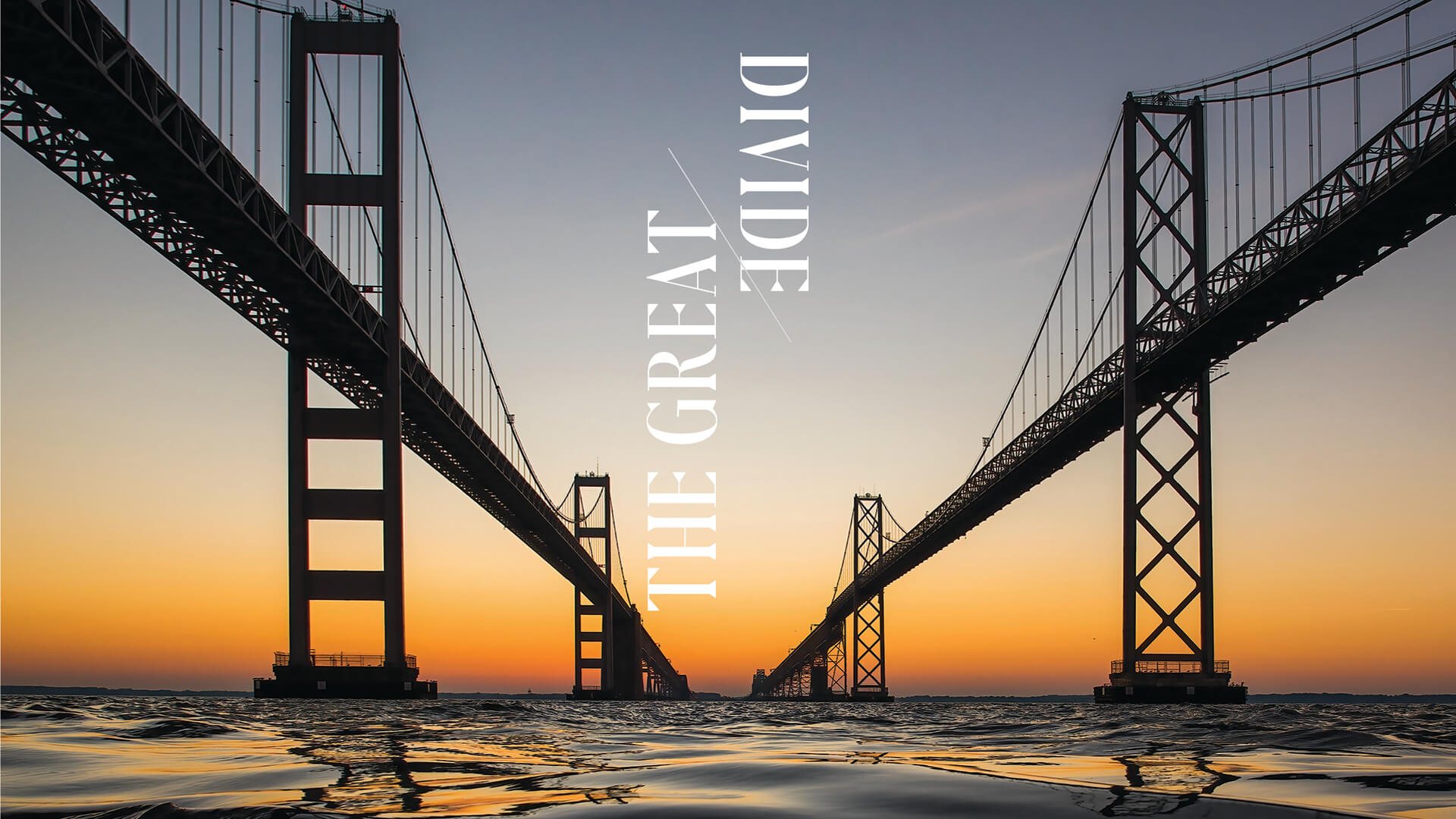

Seventy years ago, one stretch of metal and concrete changed Maryland forever.

By Lydia Woolever

Photography by Jay Fleming, Timothy Hyman, and Mike Morgan

Every summer when she was a little girl,

Lynne Outerbridge’s parents would pack up the car and pile her in with her two sisters, bathing suits and beach towels in tow, before heading south, out of Dundalk, away from the asphalt heat of Baltimore, then onwards east, toward the cool breeze of the Atlantic Ocean.

“We’d go to Ocean City, and with that, you knew, hey, we’re going to the Bay Bridge,” says Outerbridge, 65, her eyes lighting up behind thin glasses. “You were going to be in traffic, but you’d sit out there and eat snacks and play games—that was part of the experience, you know? It was fun. And when you got to the top, you saw all the boats, all the fishermen, and thought, ‘Oh, isn’t it pretty . . .’”

Years later, while working at the Department of Motor Vehicles, Outerbridge came across an open toll collector position for that very location—about 30 miles from her home in Baltimore County, just north of downtown Annapolis, on the heel of Sandy Point State Park, at the western edge of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge. She was hired in 1986, working her way up to shift supervisor and manager before retiring last April, seeing many evolutions of that iconic crossing, from the removal of the westbound tolls to the addition of E-ZPass and the traffic that came with it.

“When I was little, I thought, that looks like it would be an easy job—sit there and take money all day?” Outerbridge remembers. But that was before she descended the stairs into the tunnel that snaked beneath Route 50, climbed up through a tollbooth door, and saw the volume of vehicles, first during the prime-time commute, then more still, during the height of Maryland and Delaware beach season.

“That first summer weekend really shook me, when you looked up and saw it—headlights—as far as the eye can see,” she says. “But you got used to it.”

In fact, Outerbridge preferred the busy shifts. Regulars would bring her coffee, and when traffic stalled, she’d chat with the passersby. “Everyone had a story,” she says, not forgetting the grief she sometimes received from gridlocked travelers. During downtime, she’d read books, and on occasion, play ball in the center plaza with her colleagues until, inevitably, the cars returned.

“The collectors would yell, ‘Here they come!’ and I’d say, ‘Okay, go get it!’” she says. “We raced each other to see who could move the most vehicles.” Her record was 500 an hour. Even on days off, she would find herself there. “My husband and I used to go across all the time for vacation, to the beach, for Bike Week—we still do every year,” says Outerbridge, who recently moved to Pennsylvania. “From up there, you can really see everything. To this day, we get to the top and I say, ‘Hey, that’s my bridge.’”

Opening photo and video by Jay Fleming

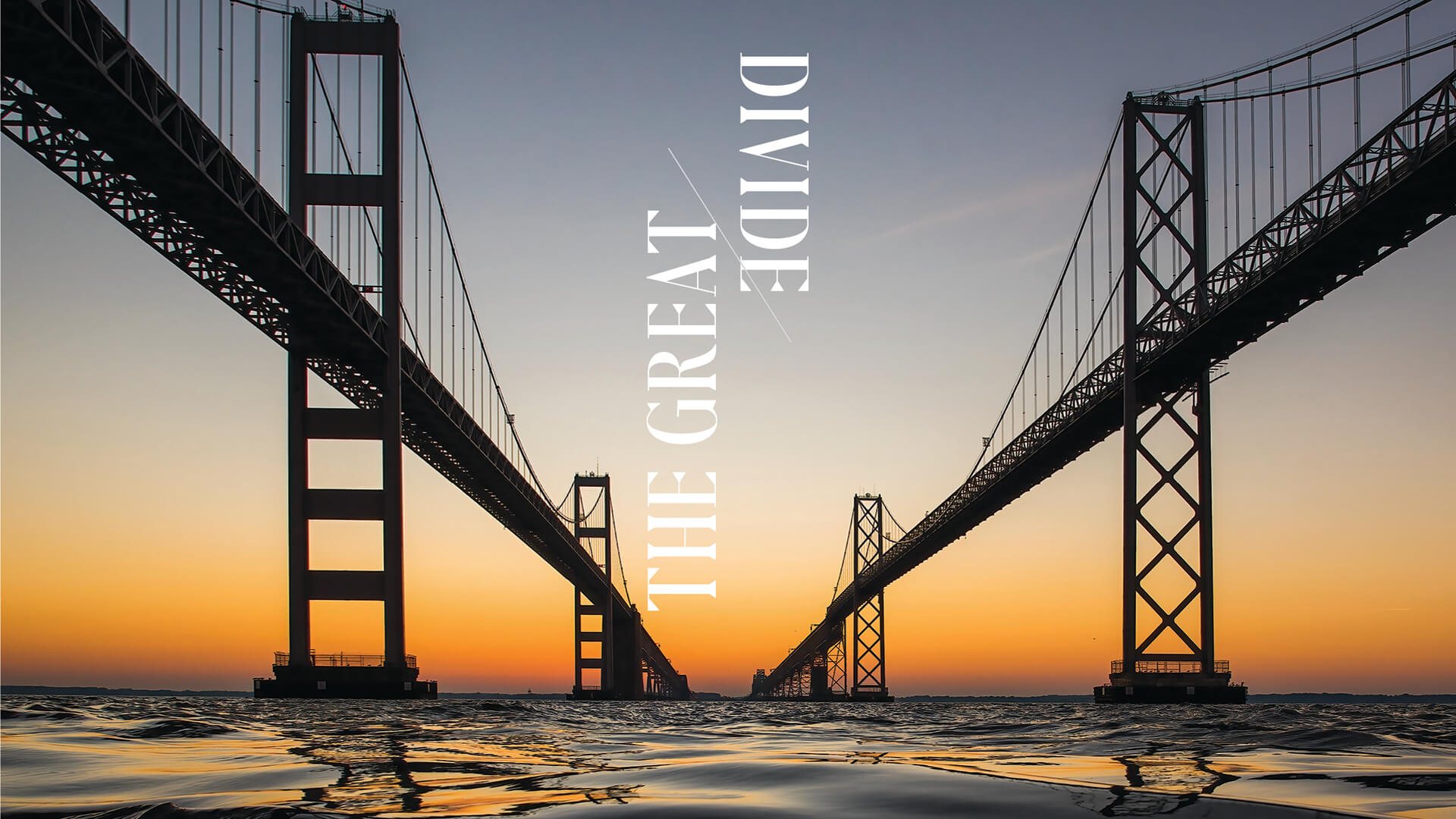

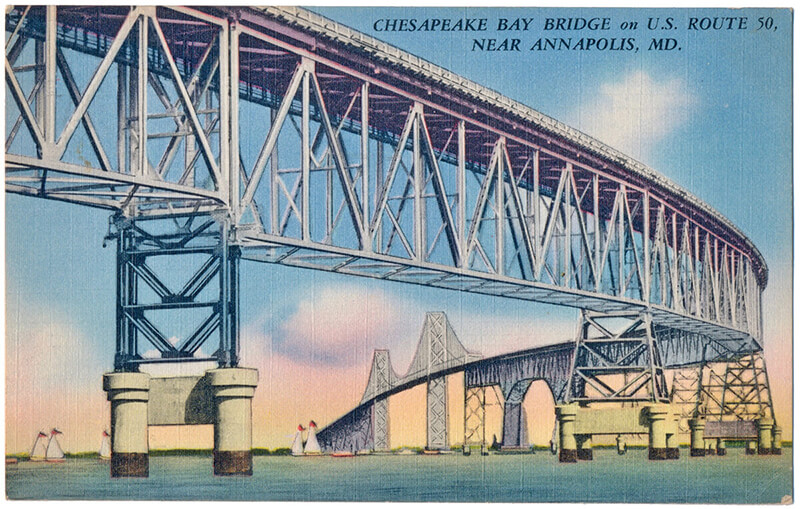

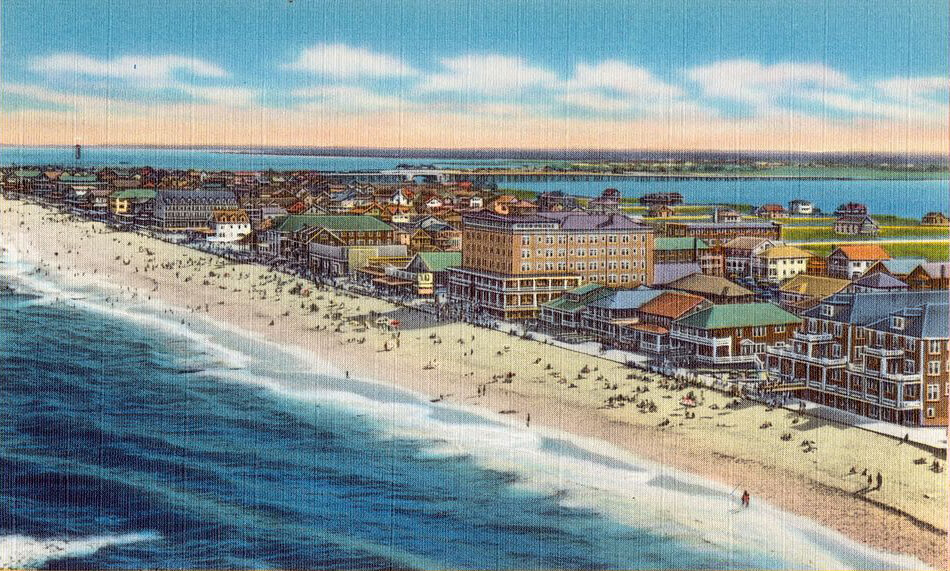

Vintage postcard of the first span, connecting both

shores of Maryland.

here is the Francis Scott Key, and the Hanover Street, and the Hatem Memorial, but as far as any Marylander is concerned, the William Preston Lane Jr. Memorial Bay Bridge—located between Annapolis in Anne Arundel County and Stevensville in Queen Anne’s—is the Maryland bridge.

Halfway down the state, two silver ribbons of steel and concrete seem to defy gravity as they float for more than four miles across the waters of the wide and majestic Chesapeake Bay, riding high—200 feet above seafaring ships and sailboats, alongside seagulls and osprey, between foggy sunrises and against dazzling sunsets—before sloping softly into the eastern and western shores, which, from up there, seem to welcome its arrival.

It is the stuff of postcards and license plates, having evolved into a quintessential symbol—a 20th-century architectural feat heralded as the great connector of the Old Line State.

The truth is, most people either love the bridge or hate it. For some of the 27 million cars that cross each year, it is the gateway to vacationland, through which sandy strands and vinegar-splashed buckets of boardwalk French fries await, no matter the traffic. For others, it’s a parking lot of taillights, or a towering deathtrap too terrifying to travel. And it's a division only likely to increase in the days ahead, as the ninth smallest and fifth densest state continues to grow, and its officials discuss what might become of this soaring infrastructure that so sparks our emotions.

But now, as it was when the first cars drove across it 70 years ago this month, as it will be with whatever iteration comes next, those iconic spans—in fact two bridges—remain an undeniable threshold. Between an otherwise disconnected state. Between economies, industries, and communities along the Chesapeake watershed. Between the past and the future. A precipice that has, for better or worse, forever altered the fate of Maryland.

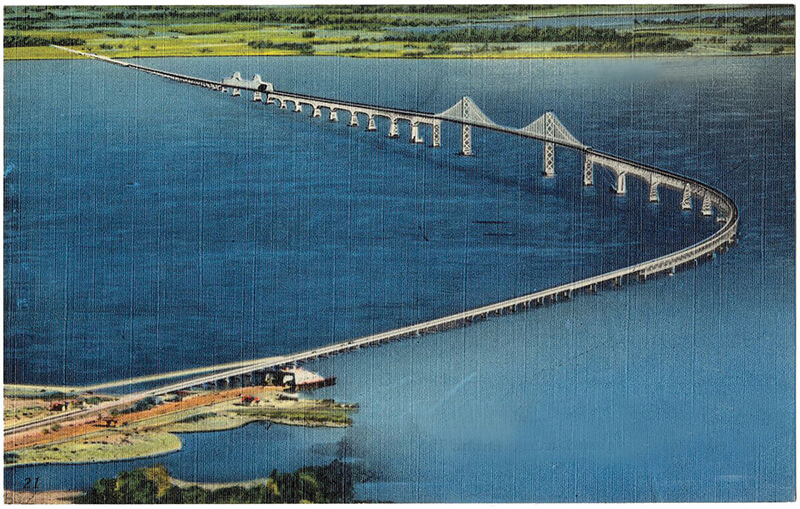

The original eastbound span, built in 1952. COURTESY OF MARYLAND DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

ong before the Bay Bridge, the body of water that it was built to cross served as the region’s primary bond and barrier. By sheer geography, the Chesapeake Bay divided the horseshoe-like landscape, with its limb-like western and eastern shores separated by the nation’s largest estuary. On either side of those brackish tides, distinct worlds developed based on a variety of factors, such as proximity to trade and access to natural resources, and with them came wholly unique cultures, ideologies, and even dialects.

Executives discuss early bridge plans. Photography by Timothy Hyman

To the west, urban areas like Baltimore City and Annapolis became epicenters of industry, transportation, and politics—part of the metropolitan corridor near the eventual capital of Washington, D.C. To the east, the nine Maryland counties of the Delmarva Peninsula, surrounded on all sides by a labyrinth of tributaries and ocean, remained resolutely rural, rooted in maritime and agricultural traditions, at times even threatening secession into neighboring Delaware and Virginia. “The bay has always isolated us,” says Pete Lesher, chief curator of the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, “but at the same time, the bay has always connected us.”

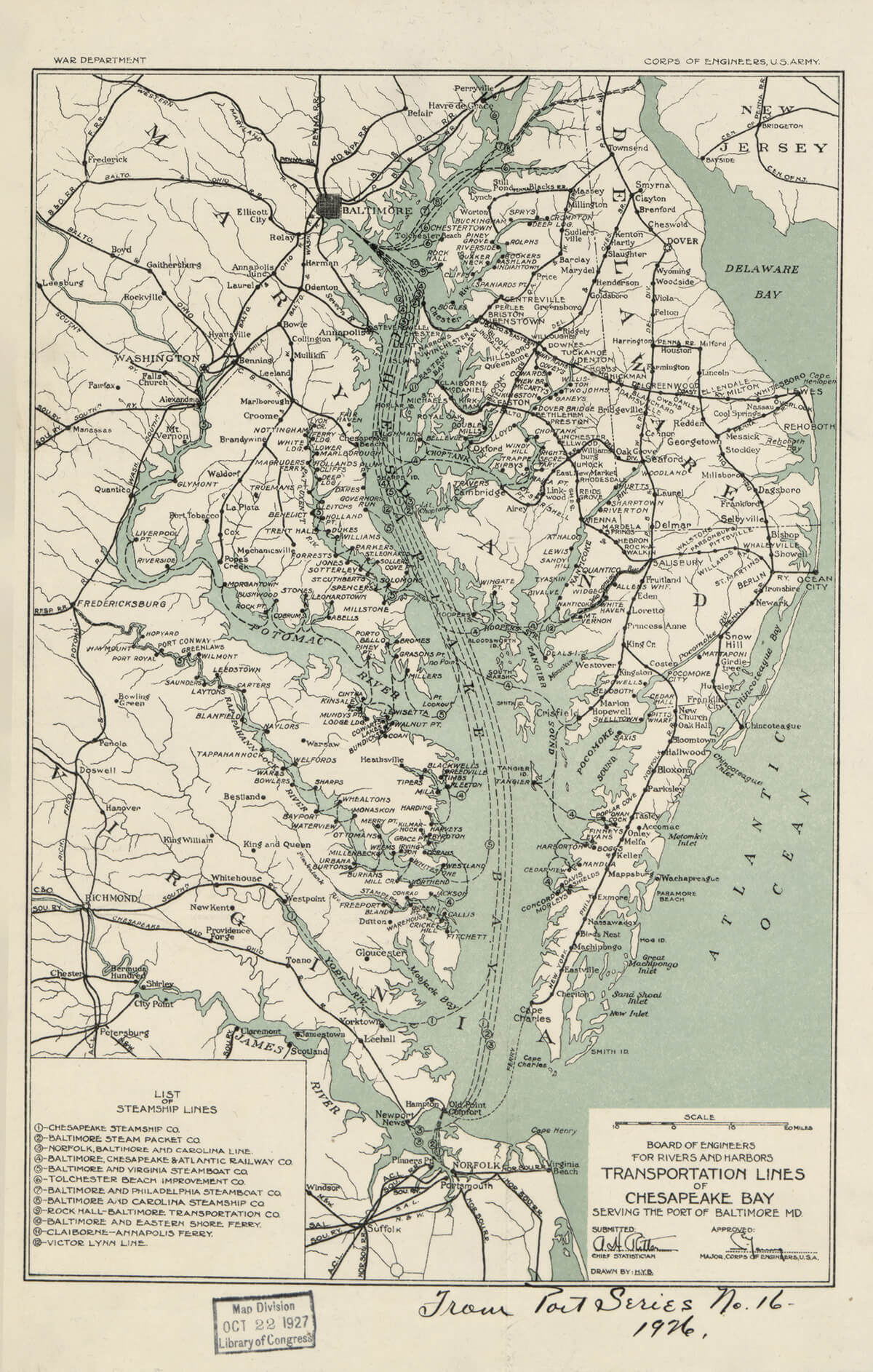

Before roads and rails, the bay was the region’s interstate highway, “a natural artery that helped us get from here to there,” says Lesher, moving people and products between its two shores. During the Colonial era, towns were situated near waterfront ports that were lifelines to the outside world, and vessels, from schooners to skipjacks, commonly swapped the seafood and produce of the east with the manufactured goods of the west.

But after the Civil War, the Chesapeake Bay became an obstacle. Suddenly train and automobile transportation better connected the Eastern Shore to rival cities like Wilmington, Philadelphia, and New York via the northern peninsula, while Baltimore hoped to keep that valuable commerce in state.

Vintage Bay Bridge postcard, c. 1955.

The first Bay Bridge discussions date back to the 1880s, but it wasn’t until 1927 that Baltimore businessmen were authorized to raise funds for construction of a crossing between Miller Island in Baltimore County and Tolchester in Kent. Those efforts were squandered by the stock market crash of ‘29, while a second attempt, mired in arguments over the location, was put on hold by World War II.

In the meantime, steamboats rose to the occasion, with ferries tempting passengers to “save 100 miles” instead of driving up and around the headwaters of the Chesapeake, and entire towns were built as rural retreats for urban clientele. The Sandy Point-Matapeake line would become the precursor for the present-day Bay Bridge, operating at one of the narrowest distances across the estuary, with notorious queues of sunburnt beachgoers waiting to head west on Sundays. At the on-ramp of the eastbound lane, you can still see remnants of the old terminal, deteriorated by weather and time, an artifact of another era.

“From the viewpoint of the average citizen, the Chesapeake Bay Bridge project has had a checkered career,” wrote The Sun in 1936. “Is there hope or isn’t there of a bridge ever materializing?”

Nothing more than “castles in the air,” surmised H.L. Mencken, created by “the artful hand of realtors.”

But after World War II, skeptics would finally be convinced, when in 1949, Governor William Preston Lane Jr. broke ground on what was then the largest public works project in the state’s history.

The massive undertaking was overseen by the J.E. Greiner Company of Baltimore, which would also engineer other local landmarks like the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel and Baltimore-Washington Parkway. Plans called for construction of what was then the third longest bridge in the world and the longest continuous steel structure over water. Rumors quickly spread that it would be too light to be safe, surely to be washed out by the wind and ice of Chesapeake winters.

“The bay has always isolated us, but at the same time, the bay has always connected us.”

The 'Louise' ferry between Baltimore and Tolchester in

Kent County, where a mini Ocean City sprung up in 1877.

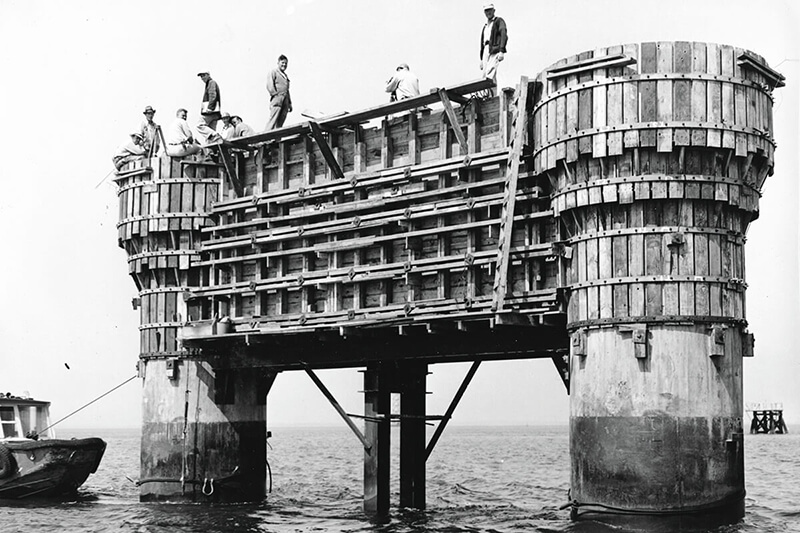

But engineers deemed the two-lane design, featuring some 60,000 tons of steel and 118,000 cubic yards of concrete (allegedly mixed with Baltimore City water for its purity), structurally sound. Sections were built by the Bethlehem Steel Company, then towed down the bay on tugboat barges to floating cranes that would lift them into position.

The bridge was actually a series of bridges, consisting of beam, girder, truss, cantilever, and suspension spans, designed to handle 3,000 cars an hour with 354-foot towers and 1,500 tons of suspension cables resting on a foundation of 57 concrete piers and 4,130 steel pilings pounded some 200 feet into the bay bottom. At the water’s surface, boats bound for the Port of Baltimore were provided 186 by 1,600 feet to navigate the shipping channel, a factor that necessitated the bridge’s elegant 90-degree curve.

“I’d never seen anything like it,” says Timothy Hyman, 84, who started his 66-year career as staff photographer for the Maryland State Highway Administration at age 12, documenting the construction of both spans. “I walked that bridge from one end to the other, many times, before there were even roads, using land, sea, and air to get my shots. . . . I was one of the many unsung people who worked on the bridge, then got out of the way.”

In the end, the bridge took three and a half years and more than six million man-hours to complete, carried out by more than 2,000 laborers from both shores, some of whom lived in a floating hotel at a nearby pier during construction. It cost $45 million, with a commemorative issue of this magazine hailing it “one of the greatest structures ever built.”

“It is a vital link in a fast-growing network of superhighways serving an ever-increasing volume of private automobile, bus, and truck traffic along the Atlantic seaboard, Maine to Florida,” wrote The Sun the weekend before its opening—one that is “expected to have a profound impact on the economy of the state, and in particular on that of the nine Eastern Shore counties.”

“I walked that bridge from one end to the other...using land, sea, and air to get my shots.”

The setting of concrete support piers. Photography by TIMOTHY HYMAN

Timothy

Hyman in his home holding

his photographs and camera

from the construction

of the first Bay Bridge. Photography by MIKE MORGAN

Prepping

the foundation for road. Photography by TIMOTHY HYMAN

On the hot summer morning of July 30, 1952, an estimated 10,000 people crowded Sandy Point to watch as then-Governor Theodore McKeldin, wearing a light suit and striped tie, cut a silk ribbon and freed the way for traffic on the brand-new Chesapeake Bay Bridge. Red, white, and blue buntings hung from the tollbooth plaza while a police-led motorcade made its way up the span. At the top, cars pulled over for passengers to look down, take pictures, and throw pennies into the bay.

“It is more than just a great, new bridge, modern in type and highly useful in purpose,” said McKeldin that day. “It is a symbol of America. It is industrial progress.”

The first cars cross the bay following opening ceremonies on July 30, 1952. AP Images

In the first 72 hours, nearly 30,000 vehicles crossed the bridge in an average six minutes at 40 miles per hour for a toll price of $1.40. Long lines backed up on both sides with motorists eager to get a look at the new crossing, while several cars ran out of gas, got flat tires, and even burst into flames. Others drove slowly, taking in the view for some 20 miles in either direction. In fact, it was supposedly up there that executives of the National Bohemian beer company invented the state’s “Land of Pleasant Living” nickname. On the other side, state police declared that the Eastern Shore “had never seen more traffic.”

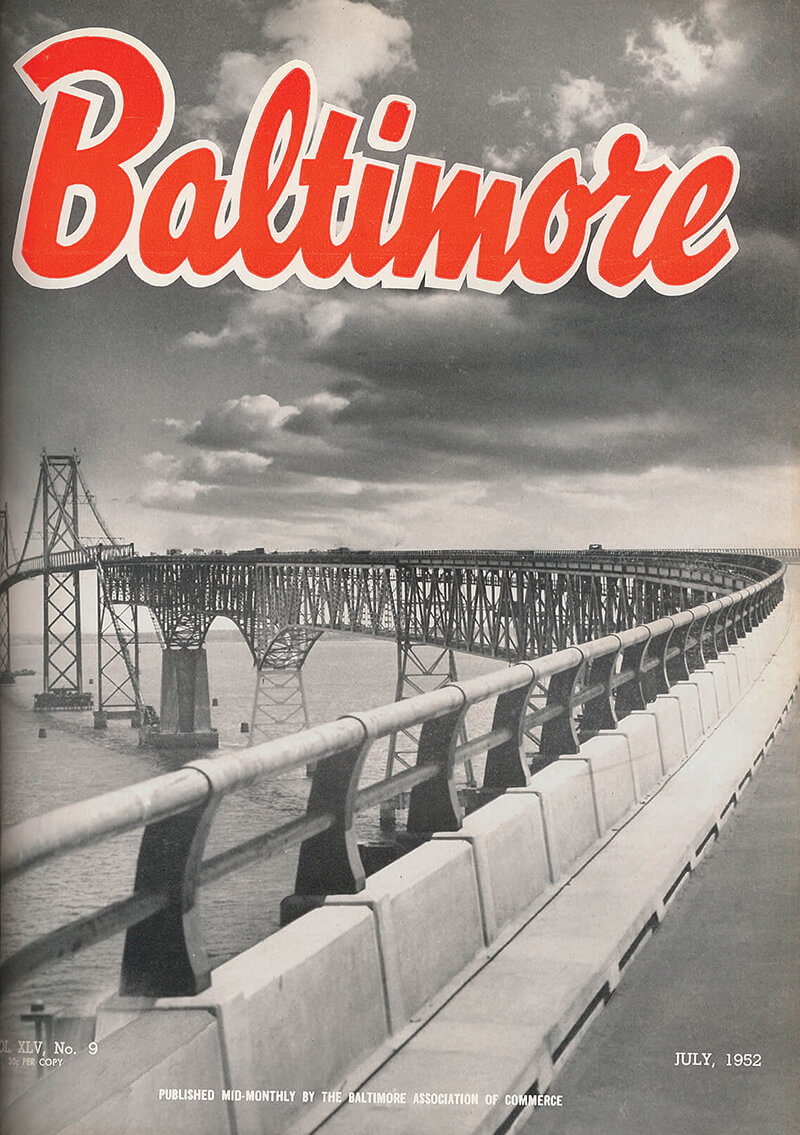

July 1952 cover of Baltimore

magazine. BALTIMORE CITY ARCHIVES, BRG29-10-46

That record, of course, would soon be broken. For years, countless advertisements tied to the new bridge ran in The Sun papers, promoting real estate, recreation, and relaxation from Kent Island to Ocean City. Among those Eastern Shore communities was a mix of excitement and apprehension.

“What the ferries did to some extent but what the bridge does with an exclamation point is strengthen those ties to Baltimore,” says Lesher, also a Talbot County councilman. “The steamboats are on borrowed time, the railroads are struggling, and the highways are what’s going to connect us, making it so much easier to travel back and forth. And of course, the more lanes you add, and the more traffic that can cross, the stronger those bonds become.”

By the mid-1960s, new debate had already begun about a second parallel span, with traffic reports stating the first would reach its maximum capacity by the summer of 1967 when Sunday traffic headed west from the ocean. Critics claimed that the State Roads Commission was not considering the whole picture and accused then-Governor J. Millard Tawes of porkbarreling to seal the votes to build.

The public voted down the addition in 1966, but it was approved a year later via an emergency bill by the General Assembly under new Governor Spiro Agnew. Mired in mounting costs, delays, and controversy, the second span nonetheless managed to open with three lanes just north of the first on June 28, 1973, costing $148 million and funded by revenue bonds to be paid back by toll dollars, like the first.

(Just months later, in an ironic twist, Agnew, now Richard Nixon’s vice president, would be forced to resign following a criminal investigation into kickbacks to his associates, including the State Roads chairman and a Greiner Company affiliate with whom he purchased 107 acres of land near the bridge.)

the dual-span

bridge today. Photography by JAY FLEMING

By this time, Ocean City was in the midst of a major transformation into Maryland’s Jersey Shore. Once a sleepy resort town and fishing village in Worcester County, the 10-mile barrier island had only grown by 259 year-round residents after the first bridge, but following the second it more than quadrupled, to 6,900 residents today.

And were it not for Mother Nature there might have been two such towns in the same vicinity. Plans for “Ocean Beach,” a 15- mile resort community dreamed up by Western Shore investors along a “Baltimore Boulevard,” were permanently washed out by a winter storm and, in 1965, Congress established that same land as the Assateague Island National Seashore.

The Atlantic seaside was an especially meaningful destination for another governor, William Donald Schaefer, who had grown tired of sitting in traffic on the way to his summer trailer in Ocean City. In 1987, he announced his seminal “Reach the Beach” initiative, which would add express lanes to the Bay Bridge, widen Route 50, and establish a travel hotline.

Though considered a success, not everyone was a fan of Schaefer’s big ideas. “Spending all that taxpayer money on U.S. 50 and calling it a ‘Reach the Beach’ program is equivalent to widening the Jones Falls Expressway under a ‘Get to Pennsylvania Faster’ sign,” wrote The Sun’s Peter Jensen in 1991. “Most hardcore Shoremen would like to blow up the Bay Bridges and let the fool chicken-neckers swim.”

Not that Schaefer always loved them back. “How’s that shithouse of an Eastern Shore?” he was once overheard asking a local delegate, leading a band of angry residents to bring a parade of wooden outhouses and bags of manure to the State House.

Secretary Harry Hughes takes the first Bay Bridge toll. Courtesy of MDTA

hether they liked it or not, the Eastern Shore would experience a watershed moment with the Bay Bridge, as projected by The New York Times in 1952: “It is expected to bring the Eastern Shore and the Western Shores of the state...into closer unity of thought and habit, and to work other important social and economic changes—all in time, of course,” particularly in counties along the beach corridor.

The crossings opened the floodgates for tourism and recreation, expanded markets for its pride-and-joy produce and seafood, increased populations with newfound commuter access to more job opportunities on the Western Shore, and with it, diversified mindsets in a region reluctant to give up Jim Crow. Since 1970, Queen Anne’s County grew from 18,500 to 50,163 residents, whereas just south, Talbot County jumped 19,428 to 37,626 since 1950, even as empty beaches now stand where forgotten ferry-era resorts like Tolchester and Claiborne once prospered.

Before he moved to Queen Anne’s full-time in 2000, resident Jay Falstad had been traveling across the Bay Bridge since 1976, watching mom-and-pop restaurants like Holly’s in Grasonville give way to Royal Farms gas stations and the old Kent Narrows drawbridge get buried beneath an overpass.

“Route 50 used to be a country highway, but it’s not one any longer,” says Falstad, director of the Queen Anne’s Conservation Association, established in 1969 to protect the county’s natural resources and rural character, notably through legal challenges to the Four Seasons retirement condominiums in Chester, which might be the largest subdivision in the Chesapeake Bay’s Critical Areas. “Our biggest fear is not just what a new crossing would do to Queen Anne’s County, but the entire Delmarva Peninsula.”

BEFORE THE FIRST BAY BRIDGE, Map of steamboat lines, c. 1926. COURTESY OF THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Falstad first got involved with the Bay Bridge in 2016, when Governor Larry Hogan announced a two-tier, multi-year National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) study, which sought to identify the best site for a new bay crossing from 14 potential locations up and down the estuary, in order to address the current and projected traffic. According to the Tier 1 study, in 2017, the bridge carried about 68,600 vehicles per day with three hours of congestion on non-summer weekdays, and 118,600 vehicles with 19 hours of congestion on summer weekends. By 2040, the state projects those an increase to seven and 22 hours, respectively.

Two years into the process, Hogan let his preference be known, disheartening some Anne Arundel and Queen Anne’s residents already beleaguered by the bridge and relieving other communities who had been scrambling to protect their shorelines: “There is only one option I will ever accept: adding a third span to our existing Bay Bridge,” he tweeted in 2019.

Community activist Jay Falstad at the Terrapin Nature Park in Queen Anne’s County on the Eastern Shore. Photography by MIKE MORGAN

And this April, he got his wish, when the Maryland Transportation Authority (MDTA) and Federal Highway Administration officially chose that 22-mile Corridor 7—just west of the Severn River Bridge in Parole to the U.S. 301-Route 50 split in Queenstown—said to likely be the cheapest, least environmentally impactful, and most congestion-relieving of all the potential routes.

No one will know exactly what that crossing will look like until the end of the multi-year Tier 2 study, which has yet to begin. A third span, a whole new replacement bridge, or even a bridge-tunnel have all been thrown around, estimated to cost up to $13.1 billion, in 2020 dollars. In Tier 1, a high-speed rail line was eliminated as an alternative, deemed too expensive for further review—though the estimated cost is unknown—while rejuvenated ferry and bus service were found unlikely to adequately reduce congestion as stand-alone options.

The latter two, in addition to other alternatives, such as variable toll rates for peak hours or high-occupancy vehicle lanes, could be considered in some combination in Tier 2, though likely still in conjunction with new construction. In the meantime, some improvements have been made, from the removal of Outerbridge’s beloved toll plaza for an all-electronic model, and this fall’s replacement of rudimentary orange barrels with automated gates for contraflow—aka that two-way traffic.

“This has been a very highly seen project for the region and, as you can imagine, we received the gamut of public comments,” says Heather Lowe, MDTA project manager for the NEPA study. “But we heard loud and clear that the congestion at the Bay Bridge now is a problem.”

Environmentalists and community activists don’t disagree.

“The traffic congestion is a problem and it needs a solution, not in 2040, but now,” says Steve Kline, president of the Eastern Shore Land Conservancy and Centreville Town Council, whose grandfather was a Sparrows Point iron worker on the first span. “However, we do not believe that a new Bay Bridge solves this problem any more durably than the previous bridge. A two-lane bridge was not sufficient for very long. A five-lane bridge has proven to not be sufficient for very long. If we add more lanes, how long will that be sufficient? Maybe it can make traffic at the bridge half as bad—for 10 years. But then it’s going to be right back to where it is now, and people will be sitting here having this same debate.”

Kline is referencing the economic concept of “induced demand,” which has found that the initial benefits of congestion relief fade within a decade, simply drawing in more cars and filling the new capacity. (See: The Baltimore Beltway.)

“If you build it, they will come,” says Erik Fisher, land-use planner for the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, who hopes the state will work to offset a new crossing’s environmental impacts, to be studied in Tier 2, such as habitat loss and water pollution in a region at the forefront of climate change. “We know more roads bring more cars. We need to think more broadly about how to get people where they want and need to go without forever expanding the pavement. We’re not building an interstate all the way to Ocean City.”

Which brings us to the great paradox: How do you alleviate traffic—including the GPS-stymied sideroads that block emergency vehicles and hinder homeowners from leaving their houses on summer weekends—without increasing development pressure in a place sought out for its rural nature?

The answer is unclear, and fingers get pointed over who created the problem in the first place.

“The bridge is not the problem—development’s the problem,” says Secretary of Transportation Jim Ports, who spend summers driving to the beach from Baltimore City. “I mean, Ocean City becomes the second largest city in the state during the summer. . . . The expansion of Queen Anne’s County, of Anne Arundel County, of other shore counties, as well as Ocean City, is what created the overcapacity problem. . . . And they’re continuing to expand now while they know it’s a problem. It’s not going to stop, whether we build a bridge or not,” emphasizing that land-use planning takes place “on the local level.”

A vintage postcard between circa 1930 and circa 1945.

“Land use should begin at the local level, but when the state makes the decision to invest billions of dollars into a transportation system to an area, they’re making a decision for the local folks,” counters Anne Arundel County Executive Steuart Pittman. “They’re putting additional development pressure on the localities by doing so, and they know that.”

Still, there are mixed messages from these small towns, who on the one hand want to keep their pastoral charm, and whose local governments on the other make decisions that put that very character at risk. In Queen Anne’s, where more than 70 percent of the workforce commutes out of county, land use for commercial real estate, high-density housing, and transportation has increased by 24, 30, and 696 percent, respectively, since 1973—when the second span was built—taking 21,000 acres of farmland with it. And in 2020, the Talbot County Council (minus Lesher) gave the greenlight to the controversial Lakeside development that would bring 2,501 homes to Trappe, population 1,228. And then there’s Ocean City.

“The question that nobody’s asking, except for maybe a couple Wicomico County commissioners, is can the beaches, which are already crowded, already having an incredibly difficult time finding staff, accommodate or handle induced demand?” poses ESLC’s Kline, who calls the traffic a “16-week-a- year problem.” “How much more can we love these beach communities before it perhaps becomes a problem of loving them too much?”

Ninety-seven percent of buildable land has been developed in Ocean City, which includes more than 10,000 hotel rooms. And updates to West Ocean City’s sewer and water service could prime the former suburb for further spillover.

“I think there’s still room to grow here,” says Ocean City Mayor Rick Meehan, a Coldwell Banker real estate agent, estimating that the majority of his town’s now eight million annual visitors come from the Bay Bridge, though others also undoubtedly arrive via the expanded Route 1 in Delaware. “I think the pleasurable culture of the Eastern Shore is affected today by the current capacity issues. . . . [A new bridge] will be certainly more beneficial than it will be detrimental.”

Meehan has signed on to a coalition of officials from 12 of Maryland’s 23 counties, some of whom have specifically asked for a replacement bridge featuring a minimum of eight lanes, larger than the six-lane Brooklyn Bridge and San Francisco Golden Gate.

“Will there be more traffic? There always will be more traffic,” says the group’s founder and Queen Anne’s commissioner-at-large Jim Moran, who owns a concrete company in Crofton. “Going from five lanes to eight lanes with shoulders for safety reasons will allow that traffic to flow,” adding that the number does indeed factor in future growth.

The exact scale of a prospective future crossing will be decided sooner than originally thought, as this June, Governor Hogan announced that he would be fully funding the $28-million Tier 2 NEPA study. “People have kicked the can down the road for literally decades . . . no one ever took the steps to say, how are we going to fix this, and that’s just what we’ve decided to do,” says Hogan. “This really has to do with the health of the entire state.”

A vintage postcard between circa 1930 and circa 1945.

Hogan, who is nearing the end of his final term, has made the bridge corridor a top priority of his administration, paving the way to the beach through Route 404 expansion, Salisbury bypass upgrades, and funding for the congested Ocean City Expressway. For the record, his Annapolis-based real estate company, currently owned by a non-blind trust and run by his brother, Timothy, also has multiple development projects in Anne Arundel County and on the Eastern Shore, among other locations.

“You have to ask yourself: With so many unanswered questions, why the rush?” says QACA’s Falstad, who hopes that the state will exhaust its transportation management strategies and non-car alternative options before constructing a multi-billion-dollar crossing. “There are other projects in Maryland that I’m sure Larry Hogan can put his name on. This doesn’t need to be one of them.”

The NEPA study’s final results will come down to the consideration of Maryland’s next governor, but in the meantime, Secretary Ports says managing the bridge, now and in the future, boils down to sheer volume. These days, 91 percent of commuting adults use a personal vehicle, and car ownership, increasingly electric or self-driving or not, continues to outpace people. The affordable $2.50 base toll—compared to the $5 Delaware Memorial or the $14 Bay Bridge-Tunnel in Virginia—likely doesn’t hurt, either.

“It’s a difficult task and you get a lot of criticism, but at the end of the day, we could do nothing, and it would really back up,” he says. “As I’ve told people on both sides of the shore: If you can tell me how to put eight gallons of water into a five-gallon bucket, I’m all ears. That’s the traffic problem that we have on the bridge—there’s just too many cars trying to go at the same time for two or three lanes of traffic. Period.”

“Our biggest fear is not just what a new crossing would do to Queen Anne's county but the entire Delmarva Peninsula.”

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAY FLEMING

All the while, amid the clamor, the 70- and 49-year-old bridges stand quietly above the Chesapeake. This Memorial Day weekend, sailboats passed between the spans below and watermen loitered around the piers while a projected 330,000 cars drove across the top.

A stone’s throw from the old ferry pier sits a brick MDTA building just south of Sandy Point, and inside, the office of Bay Bridge administrator Richard Jaramillo faces that incessant flow of traffic.

From this vantage point, Jaramillo conducts the round-the-clock orchestra that is keeping both bridges as safe and operational as possible. He coordinates with some 100 colleagues—from police and emergency response departments to maintenance and construction teams to the 24/7 operations command center—who together oversee everything from clearing debris to cleaning up accidents to inspecting the superstructure from top to bottom. At all hours, they assess weather and wind conditions, control navigational lights for ships and airplanes, and monitor more than 14 video surveillance cameras.

“It’s a juggling act that goes on constantly, every day, by the minute,” says Jaramillo, who sometimes gets stuck in the backups himself while commuting from Kent Island, “just like everyone else—we all share the pain.”

It’s a polarizing position, he knows, being at the helm of this bridge, even recalling one woman he dated before her father found out his job title: “We’re not seeing each other any longer.”

Despite his intimate knowledge, Jaramillo has no official preference for its future, though he regularly attends meetings for the Bay Bridge Reconstruction Advisory Group between state officials and community members, certain to be involved in whatever comes next.

“Richard is just here to make sure the traffic gets through safely and efficiently,” he says with a broad smile. “You deal me the cards and I’ll figure out how to make it work.”

For now, both spans are in fine condition, as they should be until 2065, says Jaramillo, who even once climbed the suspension cables all the way to the tippy-top.

“It was an experience, everything was moving, and it’s supposed to,” he says. From way up there, “it gives you a whole different level of respect and appreciation—for the people who built it, who designed it, who work on it today.”

People like photographer Timothy Hyman, who stood there more than 70 years ago, before that bridge had become the bridge.

“When I tell people what I did, they don’t believe me, then I show them the pictures,” says Hyman, sitting amongst them. “I walked with my camera, and there I was...”