Travel & Outdoors

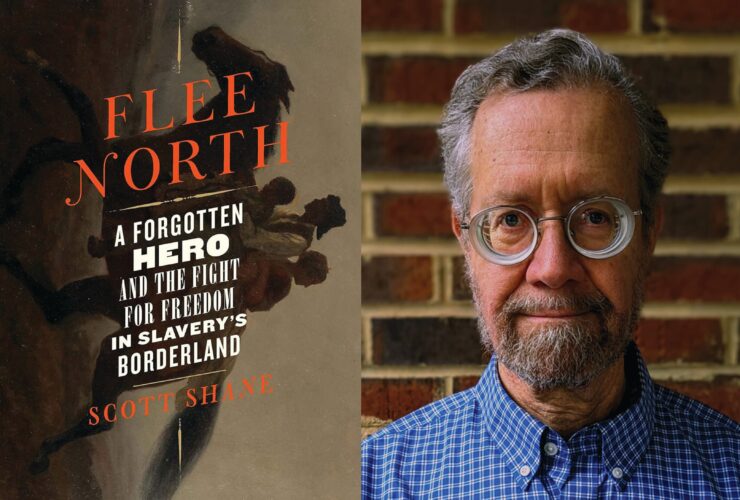

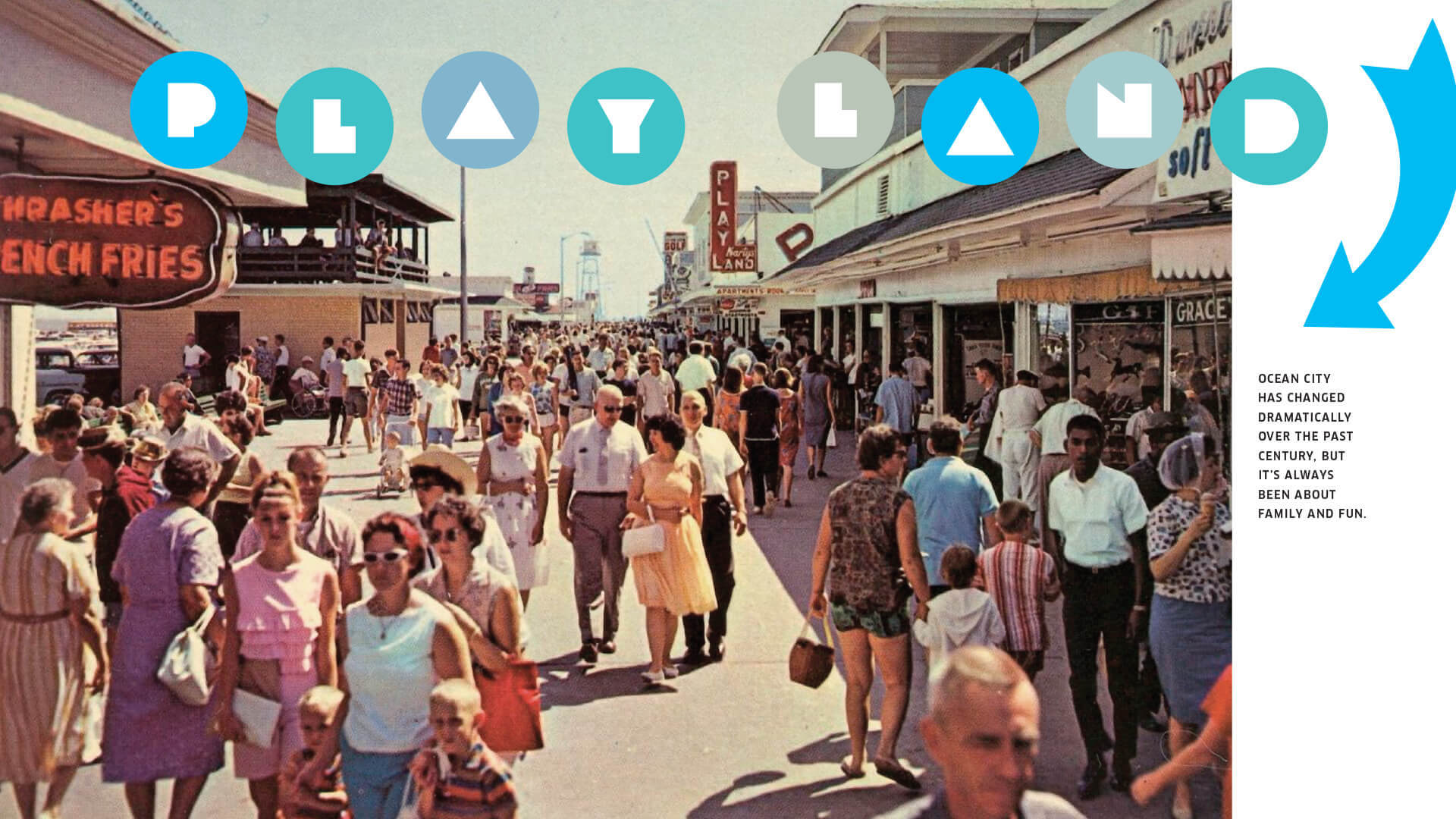

Playland

Ocean City has changed dramatically over the past century, but it’s always been about family and fun.

HEN THE TEENAGED Earl Shores

worked at Ocean City’s long-gone

Playland Amusement Park on

65th street in the summer of 1980,

he often pulled duty in the “crow’s

nest” high atop a classic carnival ride

called the Rotor. Invented in Germany a

few years after the end of World War II, the

Rotor was nothing more than a huge metal barrel. It

spun with such centrifugal force—rotating 33 times

a minute—that thrill-seekers were pinned to the

sides before the bottom of the barrel, literally, fell

out. “If the park had a throne, that was it,” says

Shores, now 62, adding his tippy-top seat, appropriately,

resembled a small metal lifeguard chair.

Below the clouds and above the screams, Shores’ job

was to keep an eye out if anyone got sick, or, from

time to time, hurt. “When someone barfed,” he says,

“you shut the ride down for a while to clean it.”

HEN THE TEENAGED Earl Shores

worked at Ocean City’s long-gone

Playland Amusement Park on

65th street in the summer of 1980,

he often pulled duty in the “crow’s

nest” high atop a classic carnival ride

called the Rotor. Invented in Germany a

few years after the end of World War II, the

Rotor was nothing more than a huge metal barrel. It

spun with such centrifugal force—rotating 33 times

a minute—that thrill-seekers were pinned to the

sides before the bottom of the barrel, literally, fell

out. “If the park had a throne, that was it,” says

Shores, now 62, adding his tippy-top seat, appropriately,

resembled a small metal lifeguard chair.

Below the clouds and above the screams, Shores’ job

was to keep an eye out if anyone got sick, or, from

time to time, hurt. “When someone barfed,” he says,

“you shut the ride down for a while to clean it.”

Vintage New Atlantic Hotel postcard.

The stand afforded Shores a view of the fabled barrier spit—a very crowded, mere 4.4 square miles—as good or better than any Cessna pilot hauling an advertising banner above the surf: STEAMED CRABS! ALL YOU CAN EAT!

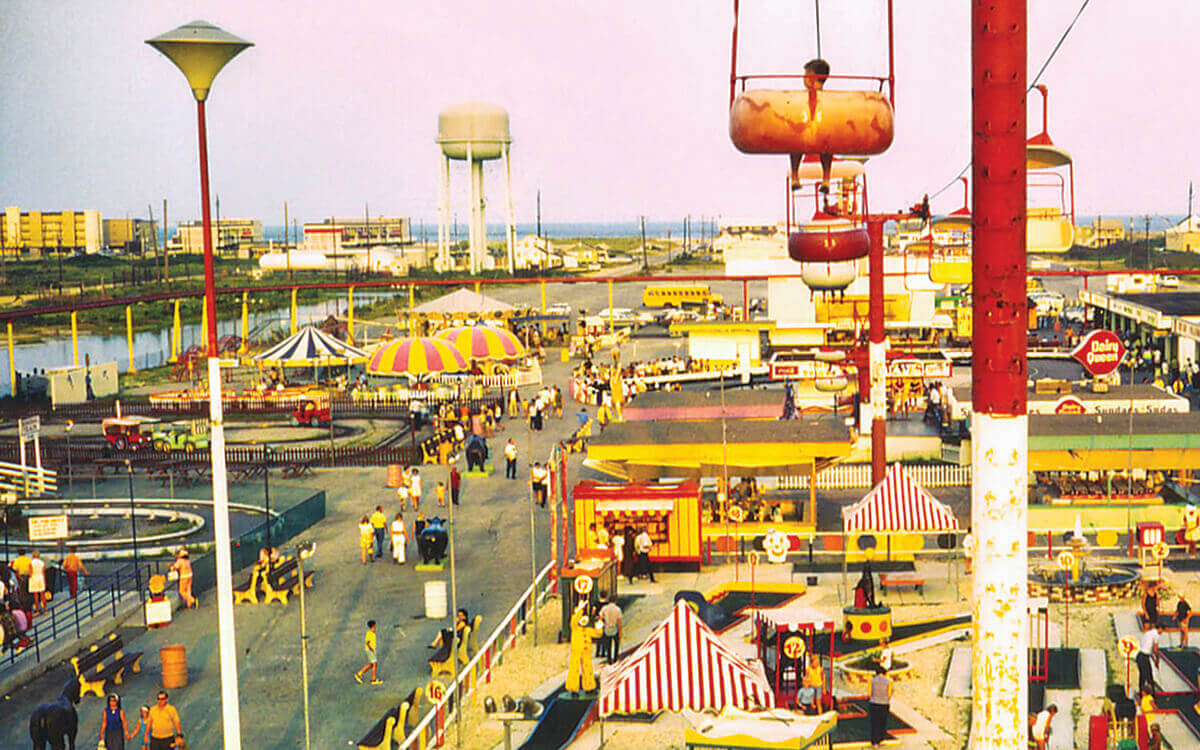

The vista encapsulated the entire history of the seaside, known as “The Ladies’ Resort to the Ocean” before the Town of Ocean City was officially incorporated in 1880—from the famous Atlantic Hotel to the south (its 1875 opening marked the beginning of a serious tourist trade) to the surfing beaches and condominium towers near the Delaware line. When Playland opened in 1965, on 65th Street, in what was then the boondocks, Annette Funicello and Frankie Avalon were doing “The Frug” in Beach Blanket Bingo. At that time, young people in Ocean City liked to head “way up north” beyond 95th street to sing along to guitars at bonfires. There was nothing there but sand dunes and Bobby Baker’s Carousel hotel at 118th street until the massive 1970s building explosion, courtesy of the Bay Bridge expansion of ’73. By the time Playland closed in 1980 to make room for Ocean City’s 15-acre Public Works Department headquarters, the once-sleepy resort and fishing community had been fully overhauled. Through four decades from 1930-1970, the town’s year-round population grew by only 547 new residents. From 1970, it increased more than five-fold to more than 8,000 residents—while exploding each summer into the state’s second-largest city with more than 300,000-plus visitors every weekend.

Earl Shores worked at Playland in 1980 and penned a memoir of his Ocean City days.

In the decades since the Playland site was converted into Ocean City’s Public Works Department, hundreds, if not thousands, of places to eat and drink, spend the night, and buy beach towels have sprung up, closed, and sprung up again. (When contractors, laborers, and engineers arrived to begin the renovation from silly to serious at Playland, they were greeted by a large, smiling clown atop the entrance.) If nothing else, today’s municipal army of trash trucks alone prove that Ocean City long ago transformed itself from town to city—one that stretches from Inlet Park at its southern end to Fenwick Island at its Delaware border.

“It was a twilight panorama,” says Shores of his summer evenings working at Playland during Ocean City’s boomtown days. “[Each night] the ocean visible on the horizon; its deep blue not far from the color of the sky as the amusement park lights were about to come on.”

Mural on the side of Fun City,

Third Street and Boardwalk.

he Baltimore Sun published classified ads

extolling Ocean City in the early 1910s as

“The finest bathing beach in the world. No

dangerous undertow. Boating and fishing

on the Sinepuxent Bay are unequaled.” It was a different

time and place. Since 1881, when a railroad line was completed across Sinepuxent to the shore, bringing rail passengers directly

to town, Ocean City had been a destination, but a quiet, more isolated

escape. Mother Nature herself would transform the barrier island in August

1933 with a hurricane that blasted open a 50-foot crevasse known as the Inlet—allowing boats to pass easily from the bay into the Atlantic and viceversa.

Known simply as “the storm” and later the Great Hurricane of 1933—the National Weather Service did not begin naming hurricanes until 1950—the

three-day surge is credited with launching the modern era of the resort. For

years, Ocean City citizens had been asking the federal government to fund

the creation of an inlet connecting the isolated Sinepuxent Bay with the

ocean. The storm essentially did the work for free.

he Baltimore Sun published classified ads

extolling Ocean City in the early 1910s as

“The finest bathing beach in the world. No

dangerous undertow. Boating and fishing

on the Sinepuxent Bay are unequaled.” It was a different

time and place. Since 1881, when a railroad line was completed across Sinepuxent to the shore, bringing rail passengers directly

to town, Ocean City had been a destination, but a quiet, more isolated

escape. Mother Nature herself would transform the barrier island in August

1933 with a hurricane that blasted open a 50-foot crevasse known as the Inlet—allowing boats to pass easily from the bay into the Atlantic and viceversa.

Known simply as “the storm” and later the Great Hurricane of 1933—the National Weather Service did not begin naming hurricanes until 1950—the

three-day surge is credited with launching the modern era of the resort. For

years, Ocean City citizens had been asking the federal government to fund

the creation of an inlet connecting the isolated Sinepuxent Bay with the

ocean. The storm essentially did the work for free.

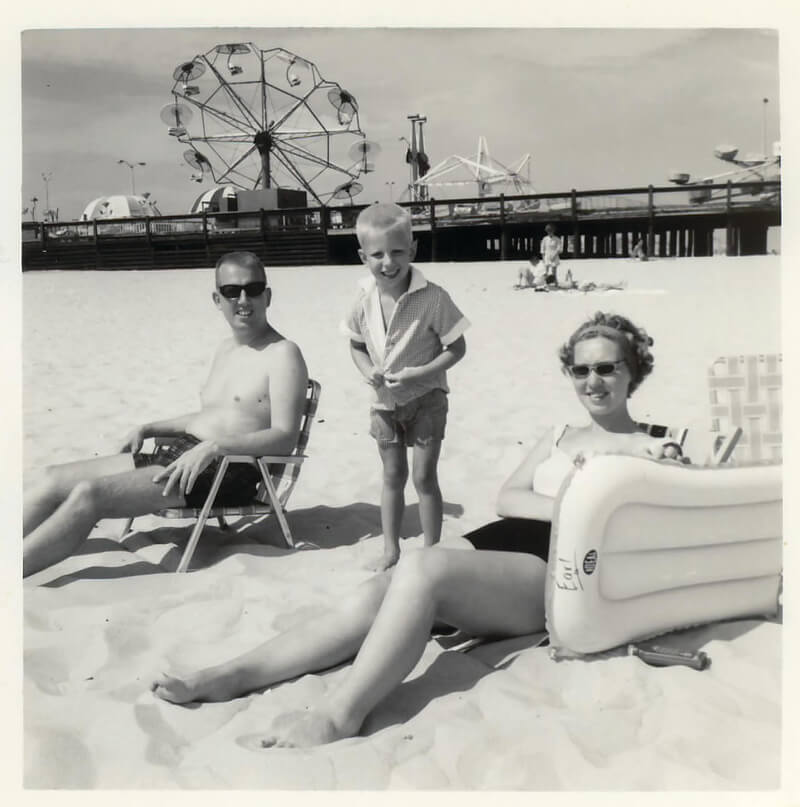

Earl Shores on the beach with his family in front of the Ocean City pier, 1964.

“Before the storm there was no way to get from the bay to the ocean, and there was no commercial harbor or bayside marinas,” says Bunk Mann, who interviewed two dozen people with first-hand experience of the storm for his 2014 book, Vanishing Ocean City. “It also ended the pound fishing industry [the practice of catching large quantities of fish in massive nets]—now you could sail out to deep water—and railroad days. The train bridge was washed out and never rebuilt.” Like Shores, who penned a memoir of his Ocean City days, Playland, Mann sells his books at the Life-Saving Station Museum at the Inlet.

Mann is a former Ocean City beach umbrella and “surf mat” vendor. In the mid-1960s, he worked a rental stand on 10th Street in front of the George Washington Hotel, which was razed in 1990 and replaced by the Americana Hotel. In 1966, he traded the glamour—low pay, but lots of smiles—of life as a beach boy for a job as a busboy at English’s Chicken. Established on 15th Street during the Kennedy Administration, it was known for its sweet potato biscuits before it closed in 2014.

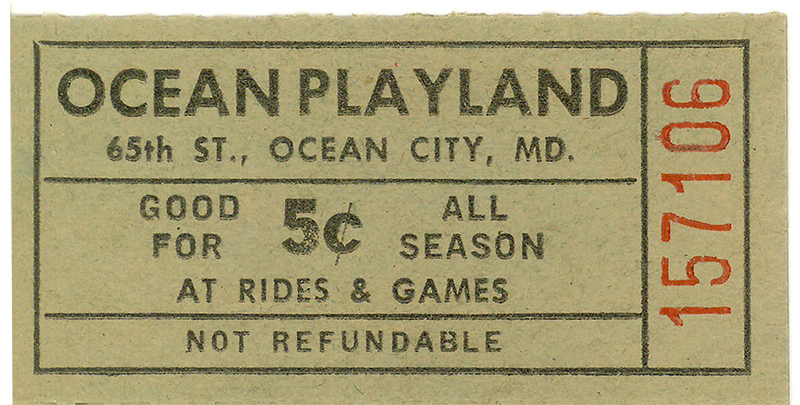

Ticket for Ocean Playland.

With the demise of itinerant fishermen and their wooden shacks along Baltimore Avenue, came the end, according to legend, of brothels as well, Mann said. “The widening of the beaches downtown were also an effect [of the hurricane],” Mann adds. “When the big rock jetties were built to keep the Inlet open it caused sand to wash up on the downtown beach, which made it more attractive. Before that, high tides would wash over the boardwalk.”

The creation of the Inlet also gave birth to the White Marlin Open, the famous billfish tournament now in its 48th year, promoted as the biggest in the world and the source of Ocean City’s official nickname today: The White Marlin Capital of the World.

The Great Hurricane of 1933 and opening of the Inlet would later serve as well as a kind of protective moat between the rising commercialization of Ocean City and the fishing camps of Assateague, which became a National Seashore in 1965. “If not for the Inlet,” Mann says, “Ocean City would have developed southward and the Assateague parks would not exist—just a continuation of hotels, bars, and T-shirt shops.” Before the storm created the Inlet, the fabled Assateague ponies were known to wander into downtown Ocean City looking for food. Echoing a Beach Boys hit from 1966, Mann says that if Congress had not preserved the shore to the south, “God only knows what would have happened to Assateague’s wild ponies!”

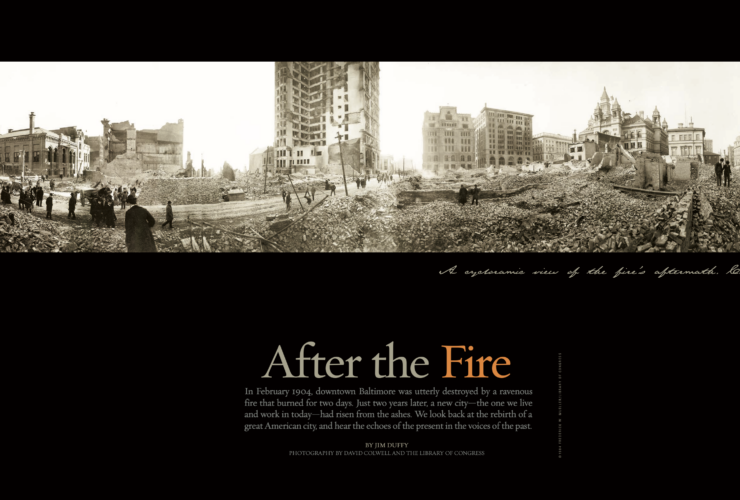

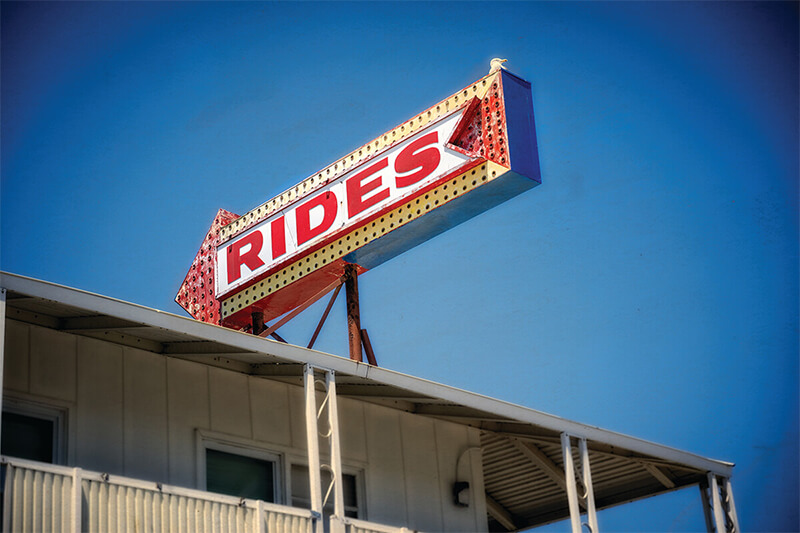

Top: Vintage image of Playland at dusk. Bottom: Two recent shots of the Ocean City board at dusk.

cean City evolved slowly at first after the hurricane of

1933 and then all at once. There was even a modest population

decline in the 1950s, which was attributed to permanent

residents moving to the mainland, either selling

or renting their high-value island property. But for Earl Shores, the

Ocean City of his youth—he was first taken there as a baby before the

dawn of JFK’s New Frontier—was always a magical place. He grew up,

and still lives, outside of Philadelphia, which, he said, made him an

“outlier” among friends who vacationed on the Jersey Shore.

cean City evolved slowly at first after the hurricane of

1933 and then all at once. There was even a modest population

decline in the 1950s, which was attributed to permanent

residents moving to the mainland, either selling

or renting their high-value island property. But for Earl Shores, the

Ocean City of his youth—he was first taken there as a baby before the

dawn of JFK’s New Frontier—was always a magical place. He grew up,

and still lives, outside of Philadelphia, which, he said, made him an

“outlier” among friends who vacationed on the Jersey Shore.

For reasons unknown, Shores says, his paternal great-grandparents began traveling to Ocean City in the 1920s. Later, when they drove, it was before the original span of the Bay Bridge was built in 1952, necessitating long road trips south through Delaware.

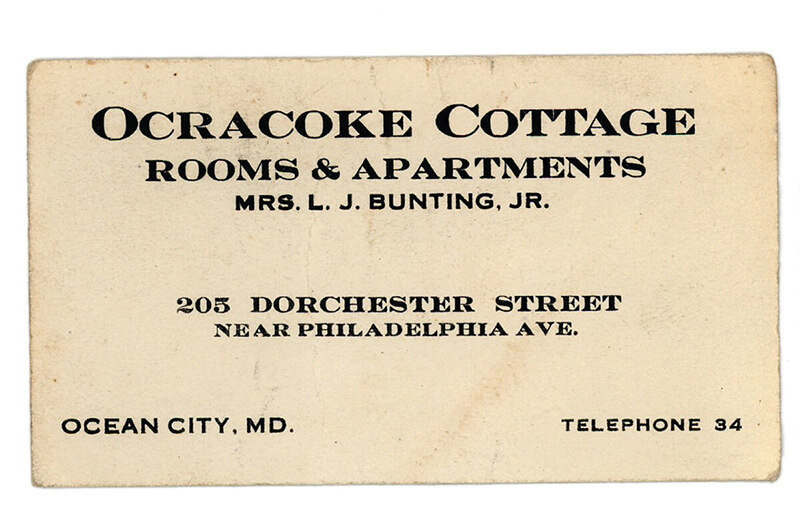

Earl Shores’ great-grandmother and Annie Bunting in the back of the Ocracoke Cottages on Dorchester Street, early 1950s.

Shores’ great-grandparents were Henry Clay Ewing, a railroad detective, and Mary Ellen Ewing, who outlived her husband by some 30 years before passing away in 1972 at age 97. She vacationed on the Maryland shore right to the end.

“Visits to Ocean City were always a family affair,” says Shores, recalling memories shared by generations—a game of Skee-Ball, fingers sticky with the caramel of Fisher’s Popcorn, established in 1937, a first leap into the surf. “My great-grandmother, my grandmother, my aunt and uncle, from the 1930s all through the ’80s, we stayed at Annie Bunting’s place on Dorchester Street,” he says. “My great-grandmother and her would spend the evening hours talking on the porch. One of my most cherished memories of Ocean City is Mrs. Bunting’s distinctive voice and the stories she used to tell.”

The inn that Annie Spencer Bunting established at 205 Dorchester Street was called the Ocracoke Cottages, after her previous home in the Outer Banks. She arrived in Ocean City in 1917, age 20, and remained until she passed in 1993.

Upon first landing on the Shore some dozen years before the great storm, Annie Bunting had worked as a maid at the Mervue, a Boardwalk hotel between Third and Fourth streets, razed in 1970, and renamed the Seaview. Around 1919, on a lot she bought for $150 according to the Bunting family, Annie built a two story, cedar-shake Cape Cod guest house with her husband, Levin Bunting.

“It took a beating from Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and then again in 2014. It’s an empty lot,” Shores says of the old Ocracoke. “I was totally unprepared for how hard that empty space was going to hit me. I cried.”

Ralph Sapia, a Baltimore attorney today, similarly grew up going to Ocean City, spending half of each year at the beach helping his parents, James and Betty Sapia, at their various eateries. His brother Vince currently operates Da Vinci’s by the Sea on the Boardwalk at 15th Street. When they were kids, the family venture was the House of Pasta on Philadelphia Avenue, now the site of a Burger King. “The only place we could get squid for our calamari,” remembers Ralph, “was Paul’s Bait and Tackle on Talbot Avenue.” Now a parking lot, Paul’s is gone, but it’s been replaced by Skip’s Bait and Tackle, which sits adjacent to its old Talbot Street location.

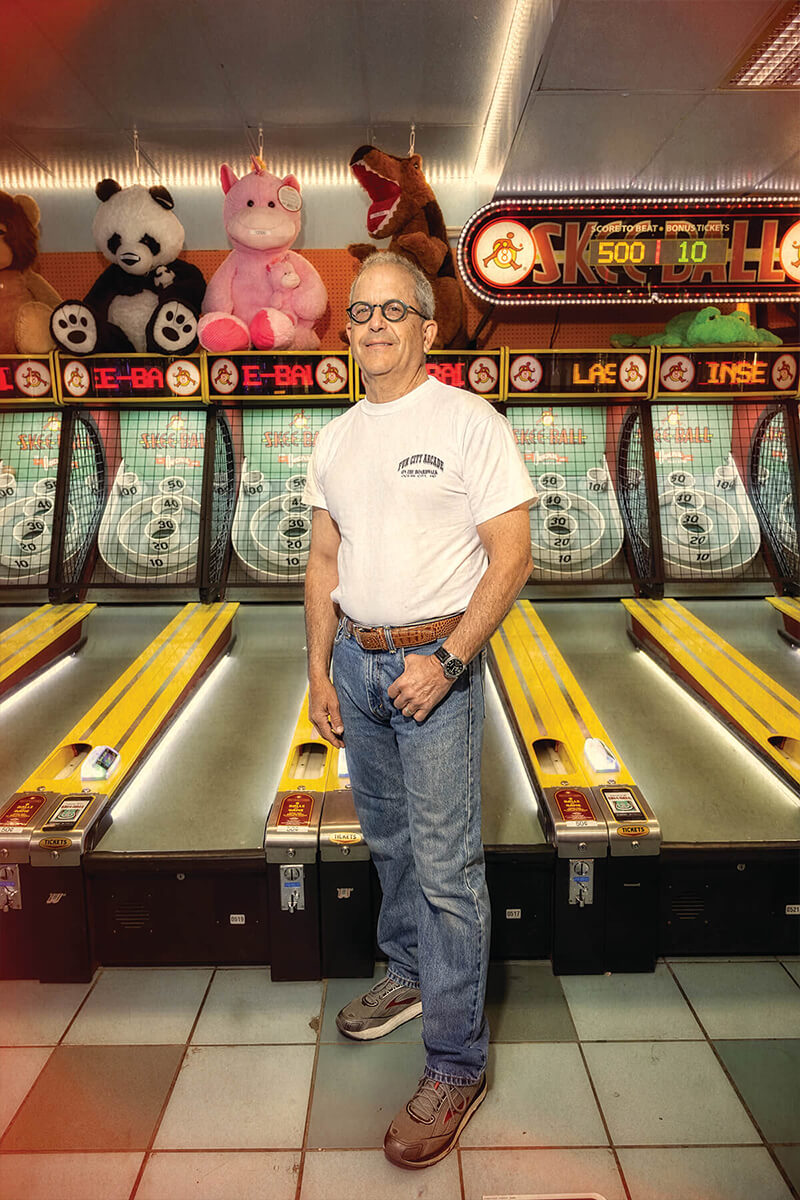

Sportland and Fun City owner Jerry Greenspan.

One of young Ralph’s best Boardwalk buddies was Jerry Greenspan, whose father, Harold, a Holocaust survivor, bought his first store on the Boardwalk in 1958. It was a department store that sold men’s and women’s clothing. “We lived behind the store with my parents, my mother’s parents, me and my sisters, and our dog, Caesar,” says Greenspan, best known for the still-popular Boardwalk arcades once owned by his father, Harold—Sportland and Fun City. “That’s the way it was.” And what once graced the Fun City address? The Maryland Inn, an elegant hotel with an Eastern Shore menu and white glove table service on the Boardwalk at Caroline Street. The Greenspans bought it in 1973, built the arcade where the screened-in porch once was, and tore the building down in 1979.

Greenspan’s earliest Ocean City memory is the “Ash Wednesday” storm of 1962, a nor’easter considered more devastating than the 1933 hurricane. Planks of the Boardwalk were seen floating down Baltimore Avenue, which resembled a river.

“Our store sold Styrofoam surfboards,” Greenspan recalls. “And my sister and I used them to paddle up and down the aisles.”

On the boardwalk: Dumser’s

Ice Cream; T-shirt shop.

irst as a kid and later as the former Ocean City correspondent

for The Baltimore Sun, I’ve witnessed several of the

town’s incarnations. When I was a kid in the 1960s, mine

was one of a half-dozen families—relatives and my father’s

tugboat and crabbing buddies—who vacationed together each summer

in Ocean City. We stayed at the Hitch Apartments on St. Louis Avenue at

Fifth Street. The rooms had adjoining doors that, when open, allowed a

kid to run the length of the building. Long removed from the founding

family, the building is now the Hitch Condominiums.

irst as a kid and later as the former Ocean City correspondent

for The Baltimore Sun, I’ve witnessed several of the

town’s incarnations. When I was a kid in the 1960s, mine

was one of a half-dozen families—relatives and my father’s

tugboat and crabbing buddies—who vacationed together each summer

in Ocean City. We stayed at the Hitch Apartments on St. Louis Avenue at

Fifth Street. The rooms had adjoining doors that, when open, allowed a

kid to run the length of the building. Long removed from the founding

family, the building is now the Hitch Condominiums.

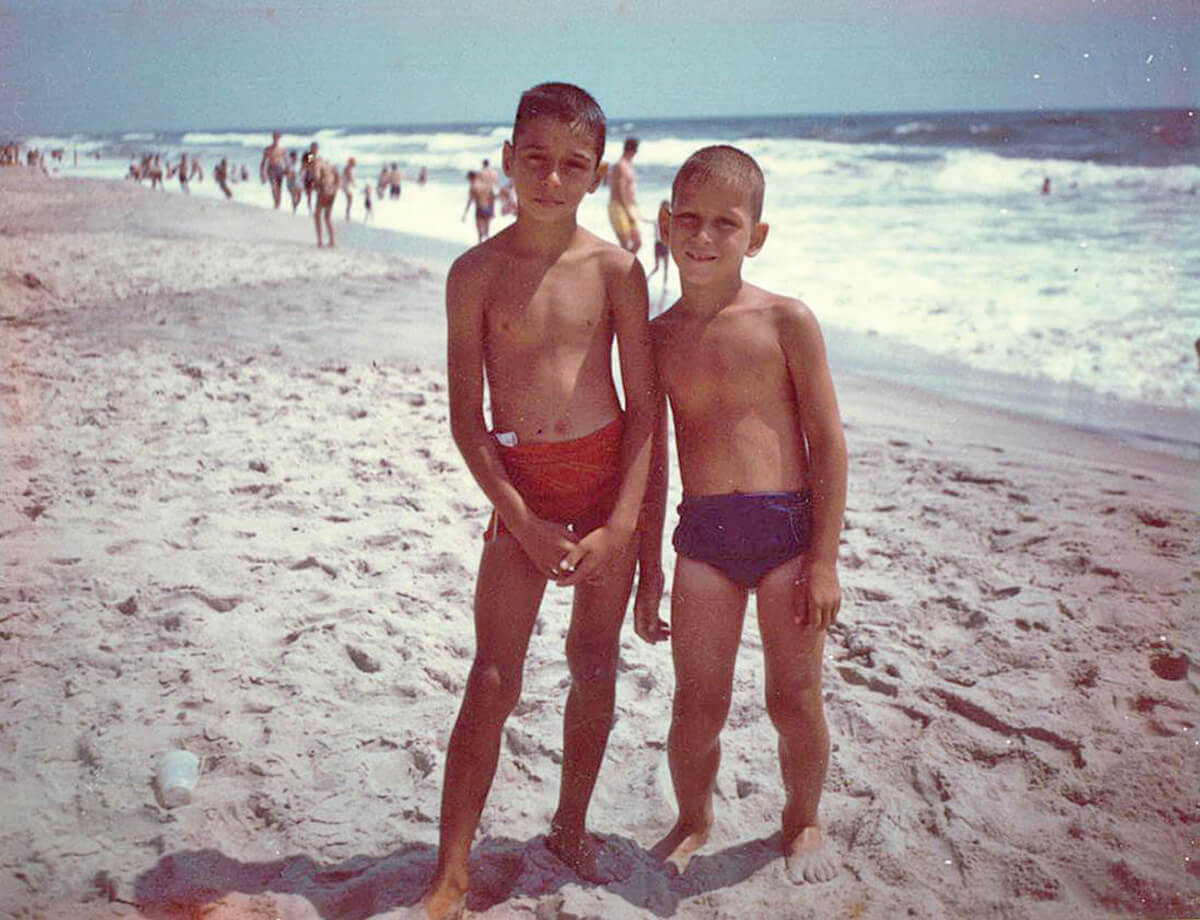

Former Sun reporter Rafael Alvarez (left) with brother Danny on the beach, 1965.

I remember how much fun it was to jump waves with my mother, who wore a bathing cap to keep water out of her ears. Not all indelible beach memories, however, are made on the beach.

I marveled as a kid as my father swiftly cleaned, fileted, and panfried dozens of Atlantic “puffer fish” caught with his best buddy, Jerome Lukowski. I also played catch in the Orioles’ World Series year of 1969 with Jerome’s son Gregory, now a retired Chesapeake Bay pilot, in the parking lot of the Hitch Apartments. We pretended we were Brooks Robinson and Paul Blair before the whole gang went to Pappy’s Beef & Beer. And I made psychedelic “spin art” on the Boardwalk—not far from a hippie shop selling posters of Frank Zappa on the toilet—by squeezing paint out of plastic bottles onto a spinning rectangle of cardboard and, after the teenager working the kiosk handed it to me in a paper frame, blowing on it to dry.

Years later, my first break as a rookie reporter in 1983 for The Baltimore Sun came when features editor Gil Watson sent me to cover Ocean City for the summer. Flush and fat in those days, the paper put my young family up in a bayside townhouse on 94th Street while I kept an office closer to the action at the Tarry-A-While Guest House on Dorchester Street and the Boardwalk.

Ocean City—a 19th-century fishing village transformed into one of the most successful beach resorts on the East Coast—was far from one of The Sun’s sought-after foreign bureaus in London and Paris, but I treated it like one. I wrote about born-again Christian surfers, a man who caught lobsters miles out at sea, and Herman “Shorty” Foster, a blind banjo player who strolled the Boardwalk with his German Shepherd guide dog, and scores of others. “They say I get around too well for a blind man,” Shorty once told me. “I can’t even see the sun shine.” On a whim, I calculated—as near as possible—how much booze was consumed over the course of the summer back in the ’80s. Consumption of beer alone was estimated at 2 million gallons. Said a drug and alcohol counselor in 1984, my second posting at the beach, “People come down here to party, not to get help.”

Stuffed toys outside an Ocean City souvenir shop.

That said, after 41 years, beer will no longer wash down plates of shrimp imperial at BJ’s On the Water, 75th Street and Bayside. Owners Billy and Maddy Carder have retired and sold the property to a restaurant group.

The landmark is being redeveloped and, like so much else in Ocean City—nearing its 150th anniversary, marked by the 1875 opening of the Atlantic Hotel—the tide comes in and the tide goes out, erasing what once was. Long gone are old-time attractions like the Jester’s Fun House just off the Boardwalk at Worcester Street, featuring a hag named Laffing Sal, a robotic rag doll now on display at the Life-Saving Museum. The spooky attraction was torn down in 1972 and replaced by the Sportland arcade.

Back in ’83 and ’84, I wore out the soles of Converse high-tops chasing stories up and down the Boardwalk and made follow-up phone calls from a push-button phone on the second floor of the Tarry-A-While. Constructed in 1897, the wooden, pitched roof, two-and-a-half-story structure with the wide porch is one of the few 19th-century buildings left. One of the first guest houses to advertise individual rooms with running water, it was purchased by the Cropper family in 1901 and remained with the Croppers for five generations.

“Bert Cropper was my Dad’s champion when we first came down here, he poured the cement for our stores,” Jerry Greenspan says of George Bertrand Cropper, a civil engineer, builder, and lifelong Ocean City resident who grew up “when the roads were sand and seashell.” Mr. Cropper died in 2005 at age 96.

At least two babies were born at the Tarry-A-While in the 1920s. It is not known how many were conceived there. In 2004, it was slated for demolition. That year, however, Paul and Kathy Davis, who’d owned the guest house for about 25 years, sold it to Bo Ruggiero, who donated the building to the town. Before ground was broken on the Belmont Tower project on its former site, the Tarry-A-While was moved 350 feet from 8 Dorchester to 108 Dorchester and renovated. The town now leases the first floor to the Ocean City Development Corporation, with rooms on the upper floors rented to lifeguards.

“We try to preserve as much of what is historical as possible,” says Glenn Irwin, executive director of the OCDC. Irwin noted that while Ocean City codified design standards in 2002 for buildings from the Inlet to Third Street, “old” Ocean City is not a certified historic district. “Only two buildings in Ocean City are listed on the National Register of Historic Places,” he says. “St. Paul’s by the Sea Protestant Episcopal Church at Baltimore Avenue and Third Street, and the Captain Robert S. Craig Cottage at 706 St. Louis Avenue. Captain Craig developed and for many years led the beach patrol.”

St. Paul’s by the Sea Protestant Episcopal Church at Baltimore Avenue and Third Street is one of the only two buildings in Ocean City listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The oldest building still standing in Ocean City is likely St. Mary’s Star of the Sea Catholic Church at 208 South Baltimore Avenue.

Asked what was the most recent heartbreaking demolition, Irwin said “the Taylor House”—a Queen Anne-style Victorian built as a hotel in 1905. Owner Larry Payne had a notion of restoring the building, and Irwin said his office discussed several options to keep the grande dame from coming down, but structural defects made it too costly. It is now a vacant lot. “A shame,” Irwin says. “We lose these older buildings to new construction or demolition by neglect.”

The best teardown and rebuild I know about occurred long ago on the West Ocean City fishing docks. It started with the towing away of the broken-down delivery truck that had been home to a man named Watterson “Mack” Miller. At the time, Mack was an all-around, whatever-needs-to-be-done employee of the Castle in the Sand, owned by Adam Showell Sr., descendent of an old resort family that has been on the Shore since receiving a British land grant in the late 17th century. In its place, a one-room wooden cottage was built for Mack by his many friends.

A police source during one of my summer reporting sojourns tipped me off to the 80-year-old Mack’s Olympian swims several miles out to sea and back, and that made for my first story about the one-time heir to the Louisville Courier-Journal fortune, who had drank and caroused away a fortune during the Roaring ’20s. I soon began visiting him in his shack, from which he walked back and forth to work each day. His lasting advice, still fresh (and finally understood) 35 years after his death in 1986: “I wouldn’t roll the dice with my blessings if I were you.”

Mack’s ashes were tossed from a clam boat into the Atlantic Ocean—the only reason the Town of Ocean City exists—where he swam for decades.

“I’d like to die while I’m swimming,” he once said, “so the fish and crabs can be my undertakers.”