Arts & Culture

New Book Explores Forgotten History of the Man Who Named the Underground Railroad

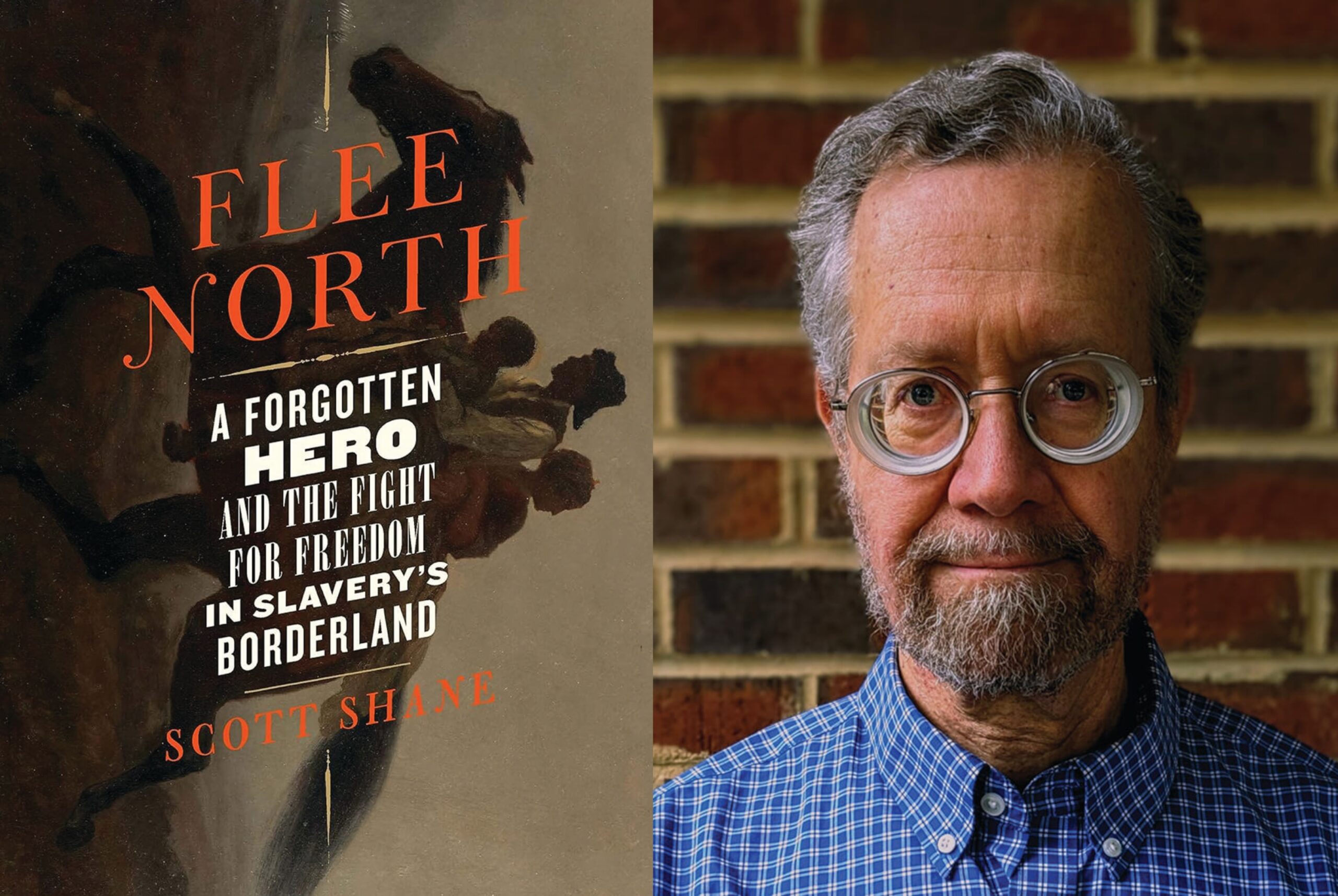

Former 'Sun' reporter Scott Shane introduces us to writer, activist, and former enslaved shoemaker Thomas Smallwood—a Harriet Tubman-worthy figure whose story is barely known.

A sharp and seasoned reporter, Scott Shane was part of two Pulitzer Prize-winning teams at The New York Times and has written two books on national security: Dismantling Utopia: How Information Ended the Soviet Union and Objective Troy: A Terrorist, A President and the Rise of the Drone. Before that, however, he spent two decades at The Baltimore Sun, stumbling at some point upon an old book that mentioned the domestic slave trade that once flourished at the Inner Harbor.

Shocked, he began gathering string over the ensuing 25 years. Eventually, a 2013 biography of Charles Torrey, a celebrated abolitionist who helped enslaved people escape from Washington and Maryland, led Shane to Torrey’s daring but forgotten partner in the dangerous work—a former enslaved individual named Thomas Smallwood.

Unlike Torrey, whose jailing in Baltimore for aiding escapees made headlines, Smallwood’s story—as heroic as you’ll find anywhere—had been lost to history. In Flee North: A Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland, Shane’s research introduces us to the writer, activist, and former enslaved shoemaker who coined the term “The Underground Railroad” as he was building it.

What piqued your interest in Smallwood? This formerly enslaved man led several hundred people, including entire families, from Washington and Maryland to freedom in the 1840s. After they’re safely in the North, he then mocks their slaveholders in pseudonymous columns in abolitionist newspapers. He’s a Harriet Tubman/Frederick Douglass-worthy figure, yet barely known.

I’d started reading about Torrey and there just wasn’t a lot about Smallwood. When he was mentioned, he comes across as sort of a Black sidekick. Then, I found the dispatches to newspapers that Smallwood had written in the Boston Public Library. Smallwood was about a dozen years older than Torrey and, to put it mildly, he seems to have better judgment. And, if you imagine trying to organize escapes, the key role is the guy who’s contacting the enslaved, which Torrey, who was white, was not in a position to do. It gradually dawned on me, “This guy is definitely the central character here.”

Smallwood is such a lively writer, joyfully ridiculing the slaveholders he’s outsmarted and, by extension, their notion of white supremacy.

There’s that wonderful passage of his that I begin the book with—about a family of slaveholders not knowing what to do when they didn’t have anyone to bring them breakfast or polish their shoes or drive their coach. They can’t take care of themselves after their “walking property,” as Smallwood puts it later, walks off.

You also chronicle the horrific details of the domestic slave trade, which includes Black bodies essentially being bred in Maryland for sale to Deep South plantations and the sexual trafficking of young Black women, referred to in ads as “fancy girls.”

The darkest thing in the book, I think, is the story of that poor young woman who gets shipped south and is taken on spec by some guy and is raped and dies. Part of the legal U.S. slave trade was basically sexual slavery. Smallwood [a married father of five] remarked about it a lot.

We’re taught about the Middle Passage, which brought roughly 500,000 enslaved Africans to U.S. soil, but not the domestic slave trade. It’s estimated twice as many enslaved people were forcibly sent to the Deep South after the international slave trade was banned in 1808, as the tobacco, cotton, and sugar industries exploded there.

I think that’s right. At The New York Times, I would occasionally ask colleagues if they knew what the domestic slave trade was. They had no idea. Very few people have any idea of the nature or the scale of it. There are many related, sub-horror stories that we haven’t digested.

Is there a more despicable person in Baltimore history than slave trader Hope Slatter, who operates off Pratt Street for a dozen years?

He’s a scoundrel and he’s a liar. He’s quite aware he’s separating families. He’s also dealing with people who were free and have been kidnapped, and he’s facilitating sexual trafficking. Yet, he’s always concerned about his reputation in Baltimore society circles. What does he call his slave pen in ads? The finest establishment of its kind in the United States.