News & Community

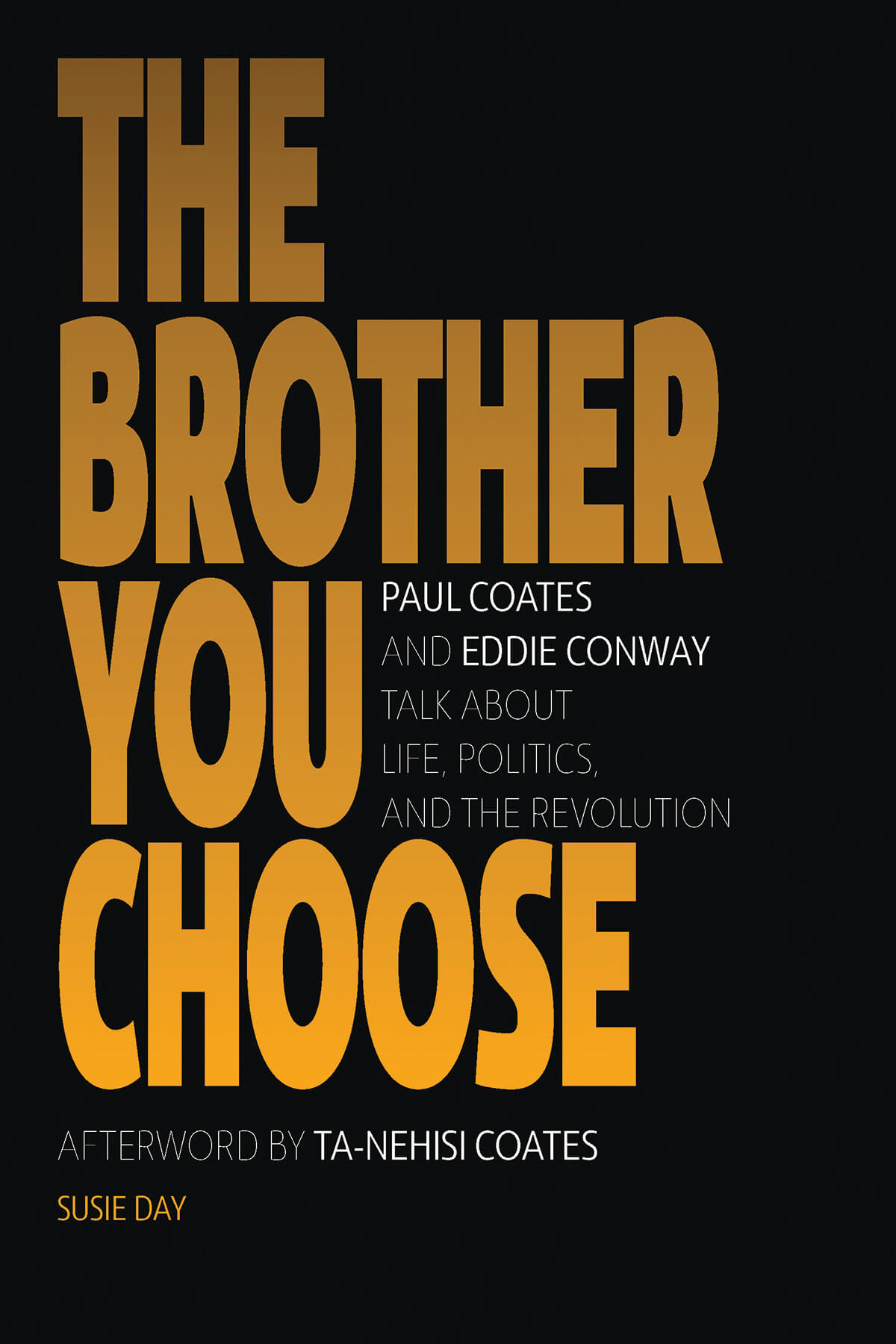

‘The Brother You Choose’ Details Enduring Bond Between Paul Coates and Eddie Conway

Coates discusses Susie Day's new book, the Black Panther Party, and his friendship with Conway.

After returning from Vietnam, Paul Coates, left, settled in Baltimore where he eventually joined the city’s chapter of the Black Panther Party and met local Panther leader Eddie Conway, right. Among other activities, they implemented free breakfast and clothing programs and a housing assistance initiative. In 1971, Conway was convicted of murdering a Baltimore police officer—he maintains his innocence to this day.

After 43 years of incarceration, he was released on parole in 2014 when an appellate court ruled that his jury had been given improper instruction, one of many trial irregularities. Coates visited Conway often and participated in legal efforts toward gaining his release. He also founded Black Classic Press—which remains a leading publisher and distributor of literature by Black writers and about the Black diaspora—initially as a way to get books to Conway and others in prison. The Brother You Choose, which author Susie Day culled from lengthy interviews with both men, brings forth relevant history from the last half-century as well as the incredible story of the two men’s enduring bond. Overall, it’s an incredibly rewarding read about Baltimore and lives committed to social change.

We recently caught up with Coates to discuss the new book, the origins of Black Classic Press, and taking his son, acclaimed writer Ta-Nehisi Coates, to visit Conway in prison.

You and Eddie Conway were not really friends when he was arrested and first incarcerated. He was an associate through the Black Panther Party in Baltimore, but you didn’t particularly like him.

Eddie and I were not close. He was a “senior” Panther, and I thought he had a bit of an attitude. But I believed, as a Panther, I was responsible for him. There were other Panthers incarerated, too, and so I was the one left in charge, although I had charges brought against me, too. I thought, “No, I can’t go and hide, I need to be there for him and meet that responsibility.” We both held the same belief in the need to confront the system. At the time, I believed the Black Panther Party, like he did, was the best way to bring about change.

How did Eddie become “the brother” you chose? And vice versa?

Prison breaks people. He could’ve gone all different directions—drugs, gangs. All that is outside of prison is in prison. But he never lost his integrity. He always held his head high. He was a model for me. There was a lot of pressure on him, too, when he went into prison. He was a Black Panther accused of killing a cop. He was not a regular prisoner walking in there. There were a lot of expectations on him to start organizing. The [prison] administration had its expectations, too. He chose me because I was always there for him.

You mention Eddie’s organizing in prison. When he talks about the prison conditions, it’s one of the most compelling parts of the book.

He continued the same work he was doing before he went to prison, from the time he was first incarcerated. He also started a prison labor union movement, a prison newsletter, and programs, and was a leader with Friend of a Friend, aimed at preventing recidivism.

When your son, the acclaimed writer Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates, was young, you took him to prison on your visits to see Eddie. Why was that important to do?

I did it because I wanted to raise him with an awareness of what the world was like. If these conditions existed in the world, then he needed to see it. And he needed to see the strength and resilience of Eddie and others who were incarcerated. If I knew about these things and did not show him, what kind of father would I be?

After the Panthers, you opened The Black Book bookstore in West Baltimore, earning your masters in library science, and launching Black Classic Press. Why?

There is the great history of Black folks, who have accomplished so much despite all the abuse, and so getting these books out became my way of giving back. I think of it as my job to put books in people’s hands. The books we publish are like bullets. They kill ignorance.