News & Community

There's A New Sheriff In Town

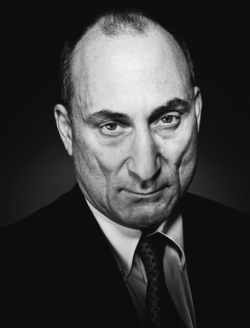

Can Gregg Bernstein make Baltimore safer?

It was a blazing Saturday morning in July when Gregg Bernstein, a 55-year-old, Jewish defense attorney, began knocking on doors in the predominantly black neighborhood where Memorial Stadium once stood. After a while, the just-declared, unknown candidate for City State’s Attorney—Baltimore’s top prosecutor—sent his wilting volunteers home and pressed on alone.

“I’m a bit of a workaholic,” Bernstein admits.

The candidate worked his way through Old Waverly, east of York Road. “I knocked on one door, it was after three in the afternoon—oh my gosh, it was awfully hot—and this older African-American woman comes to the door,” he says. “She looks at me and starts laughing.”

“‘You look terrible, come in here,’ she says, and she’s making me come into her house,” Bernstein continues, shaking his head with a self-deprecating smile. “I must’ve looked worse than I felt. She says to her daughter, ‘Come right in here and get him a bottle of water.'”

At this point, the woman had no idea who Bernstein was, or why he was knocking on her door. He’d just launched his campaign and was by no means a recognizable figure. The woman’s daughter brought him water, and finally, dehydration averted, he introduced himself.

“I ended up talking to her for 20 minutes,” he says. “And she tells me, ‘Right here on this corner, a drug dealer had been arrested, and he was right back on the street in 24 hours.'”

Canvassing door-to-door through July, August, and September, he says, “I had a lot of encounters like that.”

Expected only to gain support in white enclaves like Roland Park, Federal Hill, and Canton, Bernstein was given little chance of winning the September 14 primary nomination at the outset of his campaign. Yet, he performed well in early debates and radio appearances with Jessamy, and word trickled out that his door-to-door campaign in the city’s majority-black neighborhoods—including some of the worst crime-ridden areas—was getting a positive reception.

One of the last canvassing trips was to the Perkins Homes public housing complex in East Baltimore.

“We didn’t know what that was going to be like because it’s not a great place,” says Bernstein. “That’s where The Wire was filmed.” In the end, Bernstein spent about two hours there.

“He just walked through, knocking on doors of registered voters,” says Stephen Janis, a journalist with the Investigative Voice website who tagged along with Bernstein. “People came out and they really wanted to talk to him. It was an interesting day because the whole race was being viewed in the context of race.”

It became clear to Bernstein that many Baltimoreans, black and white, were unhappy with the way justice was meted out in the city. In September’s Democratic primary, he edged 15-year incumbent Patricia Jessamy by 1,421 votes in the most surprising upset in a citywide election in recent memory.

Says Bernstein, “People were ready for a change.”

Given Baltimore’s perennial status as one of the nation’s most murderous cities per capita, it came as no surprise that voters may have been open to change in the State’s Attorney’s Office. But whether a white candidate in a citywide race could unseat an incumbent African-American woman—in a city that is nearly 65 percent black—remained a huge question.

Except for Martin O’Malley, Baltimore hadn’t elected a white politician to citywide office in 20 years. And O’Malley won his first mayoral term aided by a split vote between two black candidates. Although highly regarded in legal circles, Bernstein had never run for office or even been involved in a campaign.

“I just believe public safety transcends race,” he says.

Bernstein grew up in a middle-class Baltimore County family, graduating from Milford Mill High School in 1973. He played point guard and captained the varsity basketball team. Not a rah-rah guy, he describes himself as more of a lead-by-example type, albeit one with a strong streak of self-sufficiency.

After his father, a buyer with Hutzler’s department store, took a new job in Illinois and his family moved, the 17-year-old stayed behind, working that summer before his freshman year at the University of Maryland.

He put himself through college, and the University of Maryland School of Law, where he edited the law review. He paid for tuition with loans and supported himself with a variety of jobs, including one as an ironworker at Bethlehem Steel in Sparrows Point.

“Local 16,” he says, recalling the steelworkers’ union. “The story I always tell people is that when you ate lunch, you had to take a bite of your sandwich and then put it back in the bag. Otherwise, it’d be covered in dust. When they opened the doors to those ovens, it was like looking into the jaws of hell. Toughest job I ever had.”

After law school, he clerked for Judge Elsbeth Bothe, in the Circuit Court of Baltimore City, before accepting an associate position with a local firm, Melnicove, Kaufman, Weiner, Smouse & Garbis.

From 1987 to 1991, he served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the District of Maryland, prosecuting experience he touted during his campaign. He founded Martin, Junghans, Snyder & Bernstein in 1993, and then joined the Baltimore office of Zuckerman Spaeder in 2004, staying until he won the general election and began organizing his transition.

He has two grown children from his first marriage and wed attorney Sheryl Goldstein seven years ago. Goldstein led the Office on Criminal Justice for Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake before stepping down when the campaign started.

“Because of Sheryl’s job, crime took up a lot of our conversation at night,” says Bernstein, who carries himself with both a natural humility and easy confidence. “As we talked, I just became more and more frustrated with what I perceived as the State’s Attorney’s office’s inability to successfully prosecute repeat violent offenders.”

Pat Jessamy had well-chronicled battles with O’Malley when he was mayor, and also, with the Baltimore City Police Department over the years. Each brought her a measure of respect as an independent leader. But over time, in some quarters, her marked distance from those institutions came to be seen as an inability to cooperate with the city’s other law enforcement partners.

In several high-profile cases over the years, including the 2009 shooting of a five-year-old girl by a Baltimore teen with a long criminal history, the Zach Sowers slaying near Patterson Park, and the murder of anti-drug crusader Angela Dawson and her family by arson, heavy criticism—fairly or not—was aimed at Jessamy.

Over the last two years, Page Croyder, who spent 21 years with the Baltimore State’s Attorney’s office, became one of many regular Jessamy critics via her Baltimore Criminal Justice blog. Croyder formerly led the City State’s Attorney’s office’s War Room, an initiative designed to alert prosecutors at Central Booking when arrests are made involving defendants with violent crime and/or gun charges on their record, ideally so that prosecutors could use the new information to increase conviction rates for such defendants.

Croyder headed a War Room study, funded though the Abell Foundation, that found that War Room offenders were convicted at exactly the same rate as non-War Room offenders, and that less than 37 percent of repeat offenders saw their parole or probation status revoked.

Taken together, the perception of a revolving door for violent offenders and Jessamy’s less-than-healthy relationship with the mayor and police department, at minimum, opened the door for a qualified challenger.

When Bernstein suggested to his wife that maybe he’d run, it caught her off guard. But once he said it, they discussed it seriously, wondering if Jessamy was truly vulnerable, realizing it would be an uphill battle.

Before a scheduled bike tour in the Czech Republic over Memorial Day, Bernstein leaned against running.

The cycling trip proved difficult, with rain every day. Yet, far from Baltimore, on long rides though steady downpours, running for office was all he could think about.

“Before I left, a friend said, ‘You have to engage in what I call “regret analysis.” Twenty years from now, if you don’t do it, how much are you going to regret it?’ That kept going around in my mind because I think public service is very important.”

And when Bernstein, sitting in his 24th floor office at Zuckerman Spaeder, overlooking the harbor, explains that he ran to make a difference in the city where he grew up and built a career, it sounds clichéd, but also sincere. Why else would someone take a major pay cut to immerse themselves in Baltimore’s intractable gun, drug, and violent crime problems—and face the public scrutiny that goes with it?

“I’ve been successful as a defense lawyer, but you reach a certain comfort zone, and I was ready for a new challenge,” he says. “I felt I had the skill set to improve the way the office operated and make it more effective.”

On the last day of their bike trip, over lunch in Prague, Bernstein recalls, his wife said, “You gotta make up your mind.”

Soon, Bernstein, his wife, and long-time Democratic operative Ann Beegle, began plotting strategy.

“We ran the campaign out of my kitchen,” Goldstein says. “My house was kind of overrun all during the summer.”

bernstein announced his candidacy in July at Calvert and East 26th St., the site of a March murder where both the victim and alleged shooter had each been charged twice previously with murder.

Introduced by Warren Brown, a politically active African-American defense attorney, Bernstein highlighted the murder as an example of the City State’s Attorney’s failure to effectively prosecute violent offenders. Bernstein’s campaign would hammer the theme on the airwaves, in debates, and during door-to-door canvassing efforts.

Jessamy, 62, cited figures that crime was down 59 percent during her tenure, but Bernstein’s message rang true to many voters. Jessamy acknowledges in an interview that the numbers didn’t translate. People didn’t feel safer. She points to the media and blames Bernstein’s campaign ads.

“A lie will go halfway around the world before the truth comes out,” she says, still sounding a bit bitter about the race. “I was the first person to talk about gang prosecutions, the first person to talk about moving from prosecuting people with drug problems to focus on guns and violent crime.”

Three weeks after Bernstein entered the race, in nearly the exact spot he launched his campaign, a Johns Hopkins research technician, Stephen Pitcairn, was stabbed to death two days before his 24th birthday. The murder, which occurred while Pitcairn was walking home from Penn Station, talking to his mom on his cell phone, reverberated though the city and media.

The man accused of murdering Pitcairn, John Wagner, had received a suspended prison term for first-degree assault in 2008. Sentenced to three years supervised probation for that conviction, Wagner was arrested several times for violating probation, including in April, when he was charged with robbing a gas station.

The crime was caught on video, but prosecutors dropped charges because the victim refused to testify. Bernstein said it was another example of the State’s Attorney’s failure to hold violent criminals accountable.

“I understand the victim didn’t want to cooperate initially, but there was a video,” Bernstein says. “You don’t drop a case at the first hearing when there’s a video.” At the time, he called it “senseless, but preventable.”

The turning point in the race, however, came in August, when police commissioner Fred Bealefeld placed a Bernstein sign in his front yard. Jessamy publicly questioned the commissioner’s integrity after learning of the sign and asked for a probe into the matter, generating headlines and bringing more scrutiny to her relationship with the police.

While Jessamy’s personal story—overcoming a segregated childhood in the South to become a city leader—is compelling, especially among older African-American voters, younger African-Americans didn’t relate to her in the same way, says Baltimore City state delegate Jill Carter, 46, daughter of local civil rights leader Walter P. Carter.

“I don’t think people my age or younger view the importance of an African-American holding on to a seat in power in the same way the older generation does,” says Carter, one of the only black elected leaders in the city not to endorse Jessamy. (She didn’t endorse Bernstein, either.)

The campaign, at times, got racially charged. Bernstein was accused of exploiting the Dawson family murders and other tragedies for political gain. Jessamy was accused of painting Bernstein as someone who would lock up minorities and turn the clock back 60 years on criminal justice.

Jessamy supporters, such as Baltimore City state senators Joan Carter Conway and Lisa Gladden, the latter a public defender by profession, downplayed the impact any single person, including the City State’s Attorney, can make in terms of public safety.

While Jessamy defended her holistic approach, Bernstein focused on effective prosecution of violent offenders and said he would continue to use drug treatment and diversion programs for minor offenders. He also said that he would, on occasion, try cases himself, something Jessamy never did.

Warren Brown says an effective prosecutor’s office can have an impact and that improving efficiency and professionalism and developing a better working relationship with the police department are crucial.

“You can talk about African-American juries that are suspect of law enforcement, but the chief prosecutor can’t be telling everybody the police suck,” Brown says, citing Jessamy’s controversial “Do Not Call” list, made public, which included names of police officers considered unreliable in court. “How do you expect African-American jurors to react? All I have to say to a prosecutor is, ‘Your boss doesn’t believe the cops.'”

Both Brown and William “Billy” Murphy, another high-profile African-American defense attorney who endorsed Bernstein, say defendants they’ve represented have long expected an easy pass in city courts.

“Believe it or not, criminals pay attention to the courts and how they work,” Murphy says. “They know it’s a revolving door they’re walking through. If that steel door is a one-way door, that affects their behavior. They don’t want to walk through it. That’s real.”

Bernstein believes people don’t give juries enough credit. There are always outliers, he says, but, by and large, he thinks that juries look at the evidence and make a decision based on that evidence.

“To the extent that the State’s Attorney’s office has not been able to get the kind of convictions that I think that they’re capable of getting,” he says, “It’s not a function of juries just not convicting people. It’s a function of the way the evidence is being presented and how effective the prosecution is. I believe that very strongly.”

Bernstein is recruiting a training director for his staff, in hopes of developing more effective prosecutors who bring stronger cases to court. He will also hire a communications director to replace Margaret Burns, who became a lightning rod in recent years, fighting Jessamy’s battles in the media.

Among his first actions, a month before his January 3 swearing-in, was a visit to Central Booking, which processes 200 defendants daily. It’s also where the “War Room,” is located. Bernstein wants to develop protocols so Assistant State’s Attorneys at Central Booking are filing the correct initial charges, and his office’s relationship with the police making arrests starts at the beginning of the process—and not with surprises in court.

His major new initiative, however, is exploring a community prosecuting model where groups of Assistant State’s Attorneys, maybe 25, take charge of prosecuting crime, top to bottom, in a geographic area. It’s been done in Brooklyn, NY, for a decade, Bernstein says, and recently, in Philadelphia and Montgomery County.

The areas would mirror police districts, and help prosecutors, again, build relationships with officers and understand the community better and why crime is occurring.

Ultimately, creating trust in the community for law enforcement, Bernstein says, helps put violent offenders away. “Baltimore needs to get away from this reputation as something just out of The Wire,” he says. “That’s not what Baltimore is about.”