Food & Drink

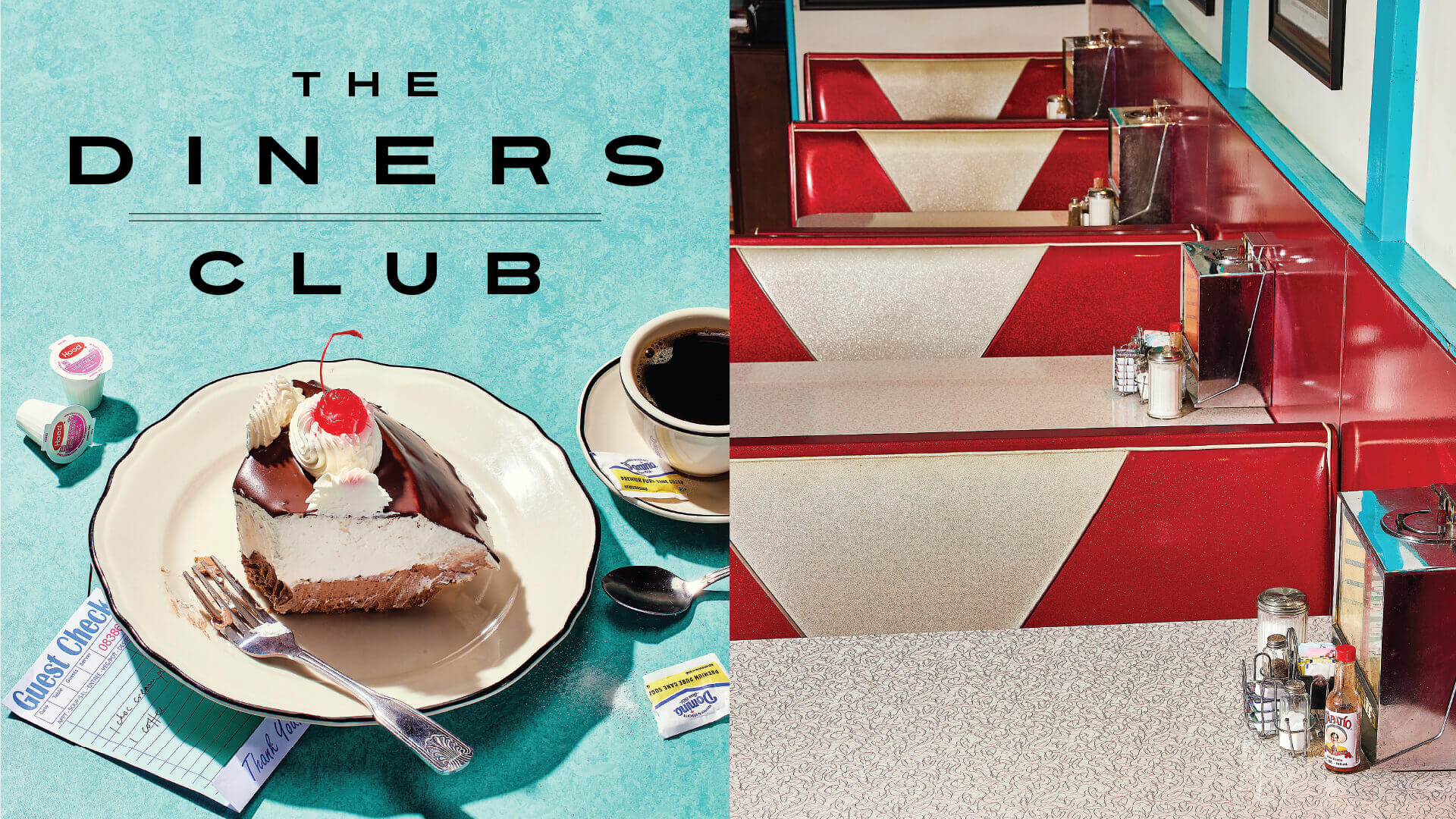

The Diners Club

The enduring joy of Baltimore's old-school eateries.

By Amy Scattergood

with Lauren Cohen, Grace Hebron, Jane Marion, Max Weiss, and Lydia Woolever

Photography By Justin Tsucalas

Food styling by Nicola Justine Davis

and you feel like you’ve entered a museum of Americana, a roadside portal to the repeating coffee cups, breakfast plates, slices of pie, and inviting Naugahyde booths that form a timeless, comforting network across the country. There’s a reason politicians invariably head to diners when they want to connect to actual people. The diner counter is the caffeinated version of the neighborhood bar, where you can sit with a refillable mug and talk up your server or your neighbor over a plate of eggs and home fries, a short stack, and a side of bacon, and feel somehow at home, whatever time it is, and wherever you are.

The history of the diner began not in Baltimore, filmmaker Barry Levinson notwithstanding, but 370 miles up I-95 in Providence, R.I. There, in 1872, the first horse-drawn “night lunch wagon” served hot, cheap food to overnight workers, newspapermen, and any hungry soul who was up too late—or too early.

These peripatetic restaurants—they could move to wherever they were needed—became “lunch cars,” then “dining cars,” then just “diners.” They got a makeover in the ’20s, getting indoor bathrooms and booths. And they became more respectable after World War II—Edward Hopper’s painting “Nighthawks,” with its lonely nighttime diner dates to 1942—adding AC, expanding the menu, welcoming families. In their heyday in the ’50s, there were some 6,000 across the country, though, then as now, they were heavily concentrated in the Northeast and dense East Coast cities like Baltimore.

These days, there are about 2,000 of what Richard J.S. Gutman, the author of four books on diners and an advisor on Levinson’s 1982 film, Diner—set in Fells Point—calls “honest-to-goodness diners.” This translates to “counter service, good value, and homestyle food,” Gutman catalogs. “Anybody can go in, and you can get whatever you want.”

The diner was always, and should still be, both affordable and democratic. So, while diners can be variable and cater to local demographics—which in these parts means crab cakes and scrapple—they should also have plenty of low-cost options, and the all-day breakfasts that have long fueled shift-workers and truckers, beer-drinkers and families alike. Simple, accessible food, says Gutman, noting that the earliest diners didn’t serve eggs—because they didn’t have stoves. “Sandwiches, pie, coffee, milk, and cigars. That was the entire menu,” he says, of the initial wagons. “And it was on a window. [Drawn] by a horse.”

The rise of fast food and food trucks changed the dining landscape—as did COVID—but the diner survives, thanks to a heavy dose of nostalgia and an ability to provide a particular kind of third space. With food costs skyrocketing, the importance of affordable food has only increased. “It’s really a place where you feel like you can do what you want and get what you want and leave feeling good about it,” says Gutman, “with some money left in your wallet.” And in the wake of the pandemic’s isolation, the comfort of the counter has become even more meaningful.

BLUE MOON

Fells Point and Federal Hill

We’ve got two tips for first-timers headed to chef Sarah Simington’s cozy, rock-and-roll-influenced fixture in Fells Point (with a second location in Federal Hill). One: Go early. (Peak wait times can creep up north of an hour.) Two: Plan to leave absolutely stuffed. Playful plates include the French toast that comes in famous flavors like Cap’n Crunch, churro, “Shut the Fluff Up” (think: a Fluffernutter in breakfast form), or a savory version layered with cheesy crab dip and diced tomatoes.

You also can’t go wrong with the massive omelets or big-as-your-face “Sin Roll” packed with thick cinnamon ribbons. Aside from the food, the best part is the lovable crew. On a recent visit, our server, Nikki, backed us up when a neighboring diner looked askance at our to-go containers by remarking, “Hey, that’s how you do it. You over-order, go home, take a nap, and then have it all over again."

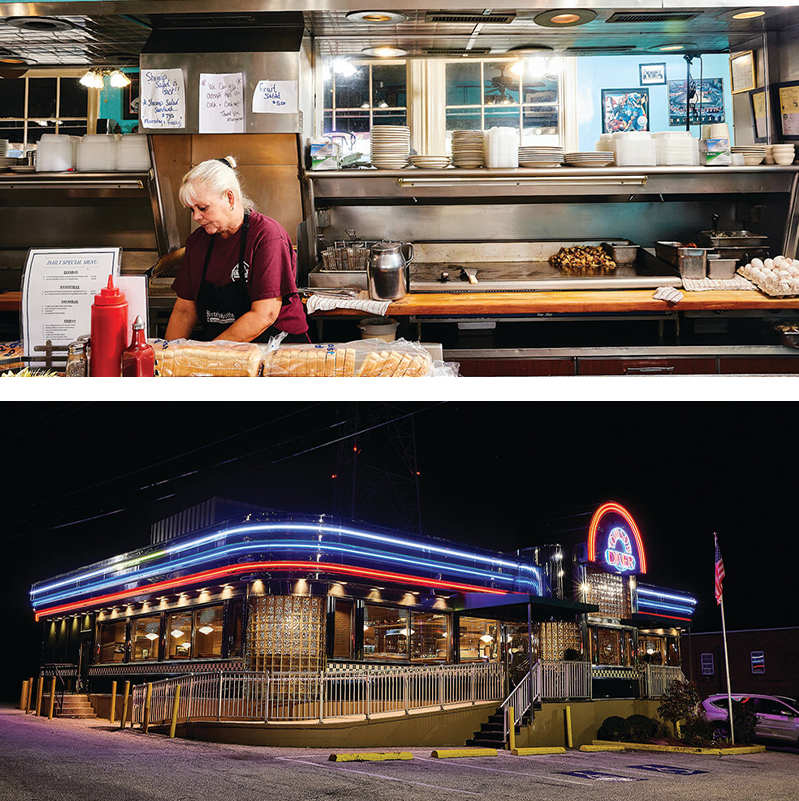

BOULEVARD DINER

Dundalk

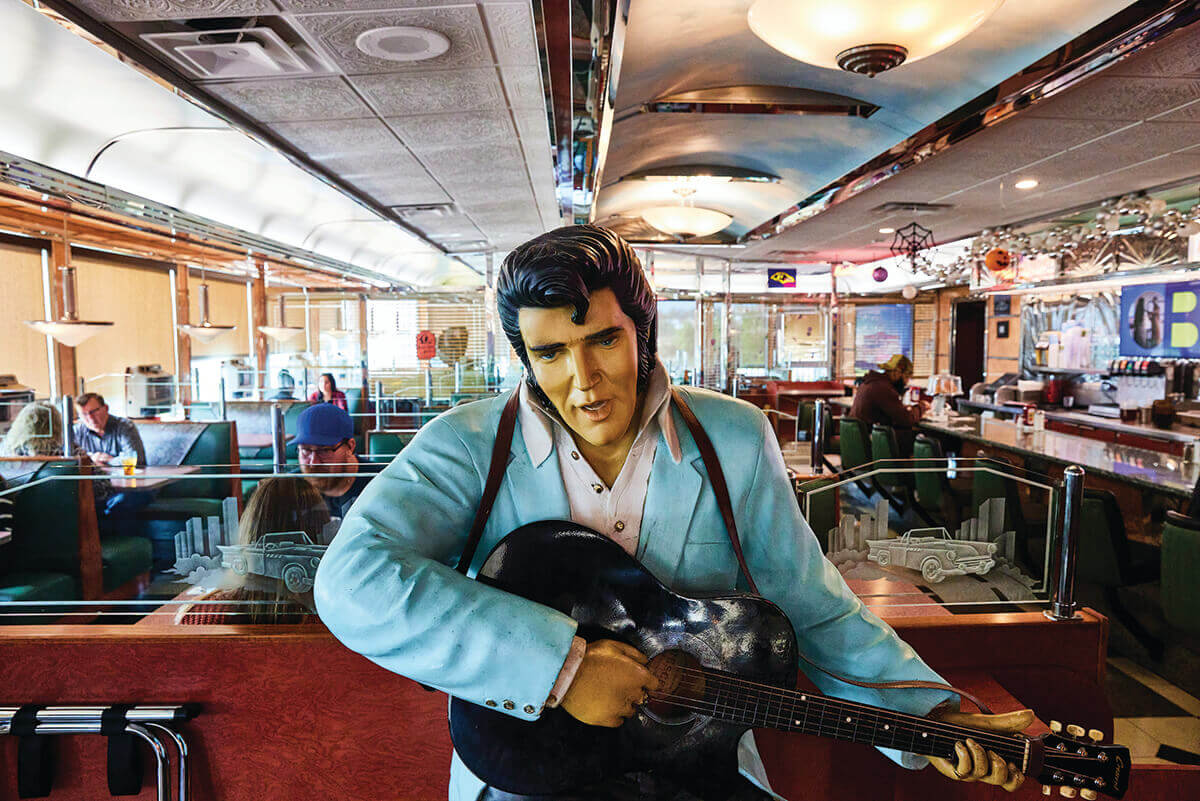

On the busy corner of Merritt and Holabird, Boulevard is an old-school, chrome-and-neon box of a diner, opened by the Tsakiris family in 2001. Statues of Betty Boop and Elvis greet you as you walk in, as well as a full bar and a pastry case jammed with cakes supplied by Yia Yia’s Bakery. There are CD jukeboxes installed at the booths—ours was turned to Jimmy Buffett (RIP), though it was the Smiths playing over the sound system—and coffee pots in formation behind the counter. Kids eat for free on Tuesdays, and there are senior discounts, Greek specials, TVs showing local news, an obligatory Guy Fieri callout, and enough space for all the politicians who swing by for photo-ops during elections. Best of all, the sour beef and dumplings is available every day.

Above: A statue of Elvis, the exterior, booths, the meatloaf, a rootbeer float, and coffee, all at Broadway Diner. Opener: Chocolate cream pie from Towson Diner; a bank of booths at Lost in the 50’s Diner.

BROADWAY DINER

Dundalk

You see the dessert case as soon as you walk through the doors of this Dundalk diner: four long shelves of fruit tarts, German chocolate cakes, cheesecakes, and cannoli, all made onsite. (And if you give two-days notice, the bakers will make your favorite dessert for you.) Open since 2003, Broadway Diner is the size of a Nissan showroom, filled with chrome, counters, and coffee machines. The booths come equipped with Rock-ola Entertainment Systems. There’s a food menu as thick as a magazine, another detailing all those desserts, plus fountain offerings and cocktails from the bar. And Guy Fieri was here. Of course he was.

Illustration by CSA IMAGES

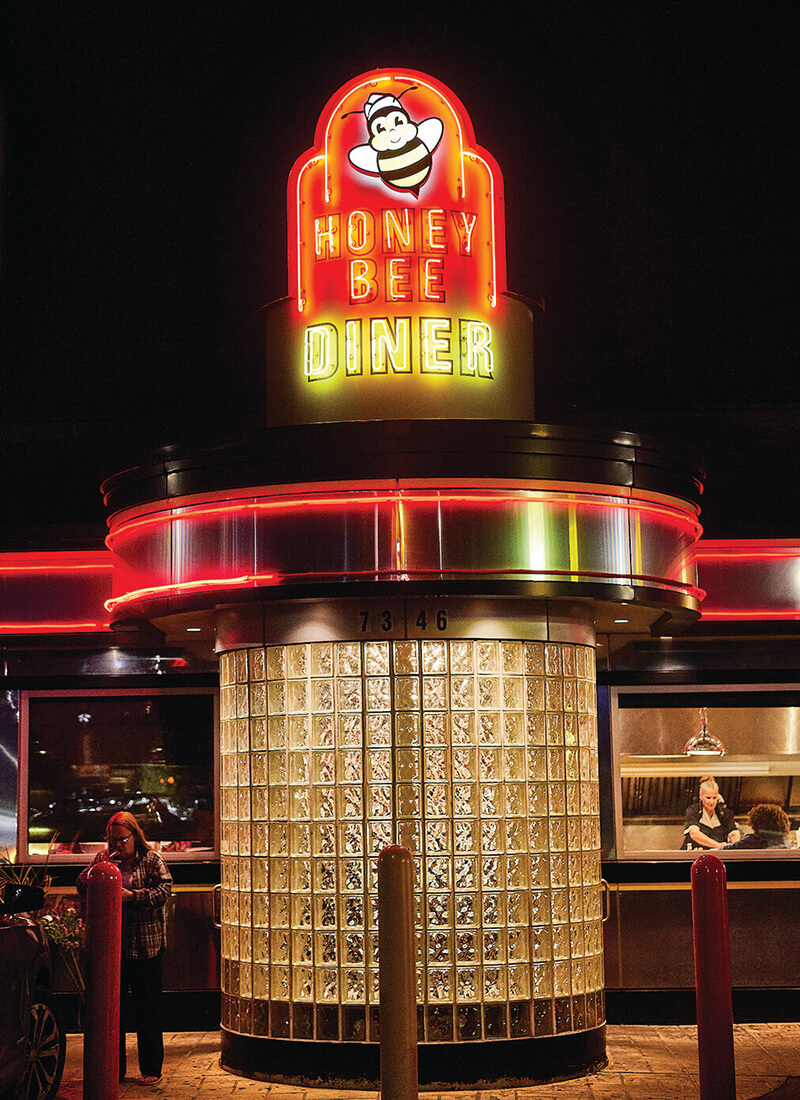

On a mid-morning weekday, the dimpled vinyl booths at Honey Bee Diner in Glen Burnie are full. A small mountain of home fries crisps on the grill as servers present plates of eggs and toast to folks sitting at the 14-seat white counter, with every seat taken. Bright red neon runs around the perimeter of the chrome ceiling like airport landing lights. Seventy percent of the diners at Honey Bee are regulars, says owner Nick Filipidis, whose parents bought the diner from its previous owner in 1974. One of the many reasons why locals regularly fill the seats is that it’s been open since 1952—always open, as it’s the last of the 24/7 diners in the region.

“As long as we have power, we’re open,” says Filipidis, who can’t remember the last time the place closed. They stayed open during various remodels and during the pandemic, though they shifted to take-out for a time. “Through all the years, we’ve never closed,” he says. For years they didn’t even have a lock on the front doors.

The first diners were only open at night, street dining cars that catered to night-shift workers and the bar crowd. As diner operators expanded their hours to include regular mealtimes at the turn of the 20th century, the diner became what diner expert Richard Gutman calls “a 24-hour phenomenon.” Over the next hundred years, diners and their hours expanded and contracted with the times—the Depression, the diner heyday of the ’50s, the fast food expansion of the ’70s—but it was the pandemic that effectively closed most of the last round-the-clock diners.

“That concept, which is one of the hallmarks, maybe it’s not that important anymore,” says Gutman. The Towson Diner was open 24-hours before COVID, but these days closes before midnight. Broadway Diner in Canton, also open 24-hours before the pandemic, now closes just before midnight on weekdays but is still open round-the-clock on the weekends.

“AS LONG AS WE HAVE POWER, WE'RE OPEN. THROUGH ALL THE YEARS, WE'VE NEVER CLOSED.”

Boulevard Diner was 24/7 when it first opened in 2001. “There was a lot of traffic, a lot of local bar business,” says owner Marc Tsakiris, and thus enough business to keep the spacious diner, on a busy Dundalk intersection, open all hours. But then the 2008 recession hit, and they shifted to round-the-clock only on weekends. “And then we just started to realize, it’s a totally different crowd at night,” says Tsakiris, whose young sons frequent the diner and work as hosts in the summer. “This is more of a family place, and it’s a little bit more of a crazy crowd at night.” Boulevard stopped its 24-hour service in 2015.

Spiros Korologos, who opened EC Diner in Ellicott City three years ago and whose father and uncles own the seven area Double T diners, says his diner has never been open 24 hours, although most of the Double T diners were open round-the-clock until the pandemic. He worked at the Double T starting when he was a teenager and took the night shift for three years. “Two to 5 a.m. was always the danger time,” he says of the hazards of staying open all night, when fights would sometimes break out. Despite the difficulties, Korologos wants to open EC Diner overnight if he can find folks to work the shifts. “My dream is to open it 24 hours,” he says, recalling his own late nights and the pleasure of finding a place that served early morning breakfast. “We’re not going to give up on it; my goal is hopefully by next summer.”

“It’s more of a hassle to go through the motions of closing everything down, because you have to be open again by five,” says Filipidis, who worked the night shift for a decade when he was younger. It hasn’t been easy. The hours are long and hard, and there are the fights among customers that often come with running a place where people come after the bars close. “Finding help has been a huge issue,” he says, and for a time they hired local cops to work security. He feels a responsibility to keep the place open round-the-clock. “It has a value,” he says. “Honey Bee’s been a part of Glen Burnie for 70 years now. People come in during snowstorms.”

“Diners have been successful for 150 years,” says Richard Gutman. “But you gotta work long hours, the price points have to be right, everything has to come together. It’s not an easy business.”

DOUBLE T

Catonsville and Other Locations

Named for the initials of its founders, Thomas Doxanas and Tony Papadis, the seven-store franchise was born in 1959 in Catonsville. Today, it’s owned by brothers Louie, John, and Tom Korologos. In Perry Hall, a silver roadside treasure box with teal and fuschia signage is our signal to pull over. The location on Belair Road is also frozen in the ’50s, with its checkered floors, red barstools, iced desserts behind a wall of glass, and specials—eggplant Parm, prime rib, whole rockfish, and broiled trout—scribbled on a small blackboard. Here, regulars are crazy about chicken fingers, jumbo saucy chicken wings, and all-day breakfast items: omelets, Benedicts, burritos, breakfast sandwiches and skillets, with a laundry list of add-ons. Did we mention there’s a bar, too?

EC DINER

Ellicott City

If your GPS happens to glitch on your way to Ellicott City’s newish namesake diner on Baltimore National Pike, just look for the huge sign flashing “Extreme Shakes.” The thick treats with outrageous garnishes (ours came with a whole Chipwich and a blondie on top) were among the additions that the former Double T Diner adopted when new owners John Kanellopoulos and Spiros Korologos took over in 2020. The interior got an upgrade, too, with new furniture and retro light fixtures. But classics—including hefty pastrami Reubens, all-day breakfasts, and traditional Greek gyro and souvlaki platters—still remain on the novel of a menu. Also noteworthy: the crab cakes, which might taste familiar to some. Kanellopoulos brought the recipe over from his other restaurant, By the Docks in Middle River.

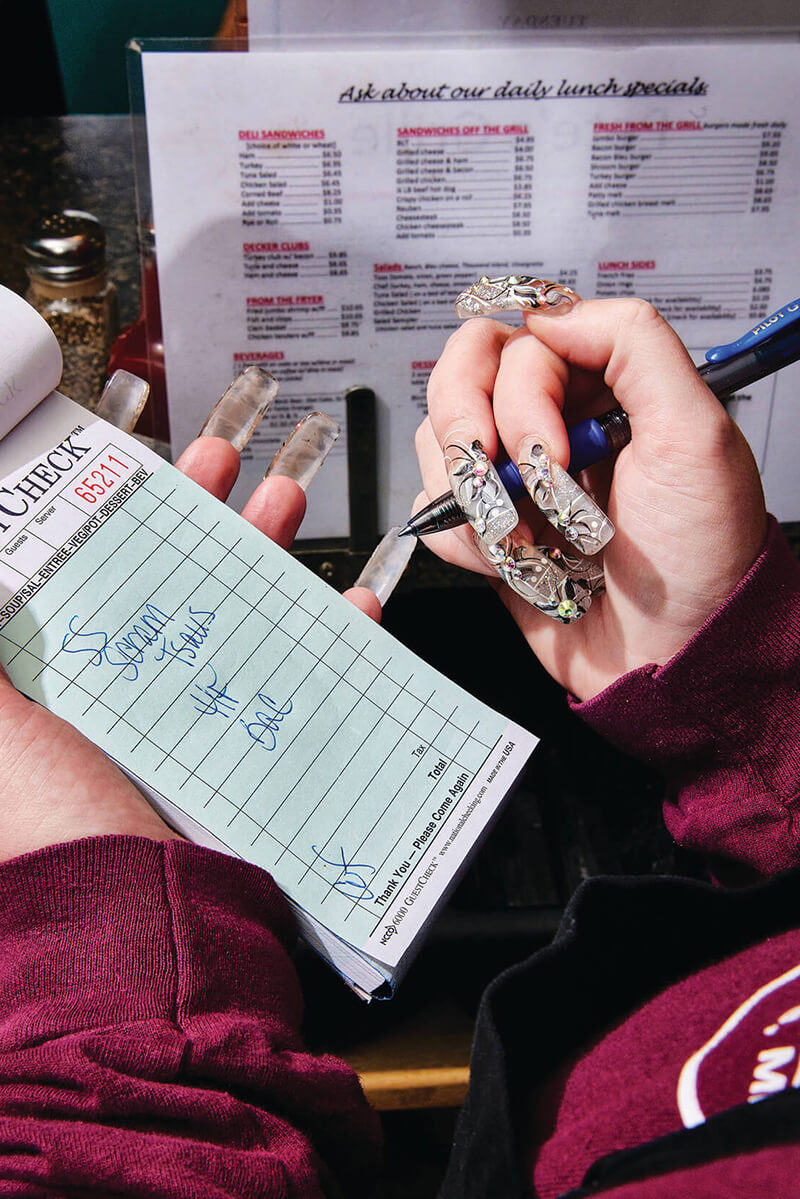

Above: Nighttime exterior with neon, eggs on the griddle, pancakes and syrup, juggling plates, the interior, a coffee pot, and a guest check, all at Honey Bee Diner.

HONEY BEE DINER

Glen Burnie

This 71-year-old diner has regulars who have been heading through the always-open doors for decades. Two families have owned it since the beginning; Honey Bee’s cook has been working the grill for over 20 years. The menu is loaded with the classic diner fare, with a few specialties (M&M pancakes, scrapple wraps, Texas toast dipped in frosted flakes) thrown in for good measure. With a long counter on one side of the space and booths filling the other, it’s neither the cavern of many roadside diners nor the tight space of some old city spaces, but the kind of cozy restaurant where regulars feel at home—and have been coming back, anytime of the day or night, for 70 years.

KAY’S PLACE

Remington

The blue neon sign reading Wyman Park Restaurant still glows on the corner of Howard and East 25th streets, but now, this is Kay’s Place. Owner Cia Carter bought the neighborhood breakfast counter back in 2021, retaining both the space’s old-school, no-frills feel and its classic, comfort-food cooking. Just before noon on a recent Tuesday, all the maroon booths and most of the stools were packed. Wyman Park regulars are still showing up and Carter has brought in some new fans, too (her other dining establishment, Miss Carter’s Kitchen in West Baltimore, is a preferred choice for fueling up by the Ravens’ own Lamar Jackson). The gyros and crab cakes that Wyman Park once served are gone, but stellar burgers and stacks of fluffy flapjacks are slung from the flattop grill, Belgian waffles are poured to order, and in true Charm City fashion, there’s lake trout (or whiting) for breakfast or lunch.

Above: The busy counter, an order of French toast, shelves of supplies, a breakfast sandwich, and a jukebox at Lost in the 50’s Diner.

LOST IN THE 50’S DINER

Hamilton

Look up the word diner in the dictionary and you’ll likely find an apt description of this adorable Hamilton eatery that beckons with its neon sign along Harford Road. While it just opened in 2009, it could have fooled us: Lost in the 50’s has all the hallmarks of a vintage roadside eatery—sparkly vinyl booths with Formica tables and the requisite jukeboxes, black-andwhite checkered floors, congenial servers, no-fuss coffee, and satisfying breakfast staples with Eisenhower-era prices. (That’s $3.50 for a scrapple and egg sandwich; $4 for a short stack or waffles; $5.50 for a Coney Island hot dog and chips.) In other words, there's no avocado toast or acai bowls, no surprise surcharge, and no one rushing us out after an hour because the table is spoken for. In fact, we could sit here all day. Who says that being stuck in the past is a bad thing?

THE NAUTILUS DINER & RESTAURANT

Timonium

You’ve heard of comfort food—well, Nautilus is a comfort restaurant. There’s a pleasing sameness to every visit here. It’s just a straight-up professional restaurant, from the host to the waitstaff to the back of the house. The place is huge so there’s rarely a wait—but if there is one, it’ll be short and, yes, efficient. The ice water will come out right away and, if you’ve come for breakfast, runners serving coffee will magically materialize at your table whenever you need a refill. The giant menu is stocked with traditional Greek-influenced diner fare—so there’s souvlaki, spinach pie, and moussaka alongside an assortment of sandwiches, burgers, Blue Plate specials, Italian entrees, and pretty much anything else under the sun. (We went in one night craving nachos and damned if there wasn’t a perfectly respectable version on offer.) There’s also breakfast all day (including the inevitable “Hungry Man Special,” which could feed a family of four) and a case of eye-popping house-made baked goods up front to tempt you if you’ve saved a little room—and you should.

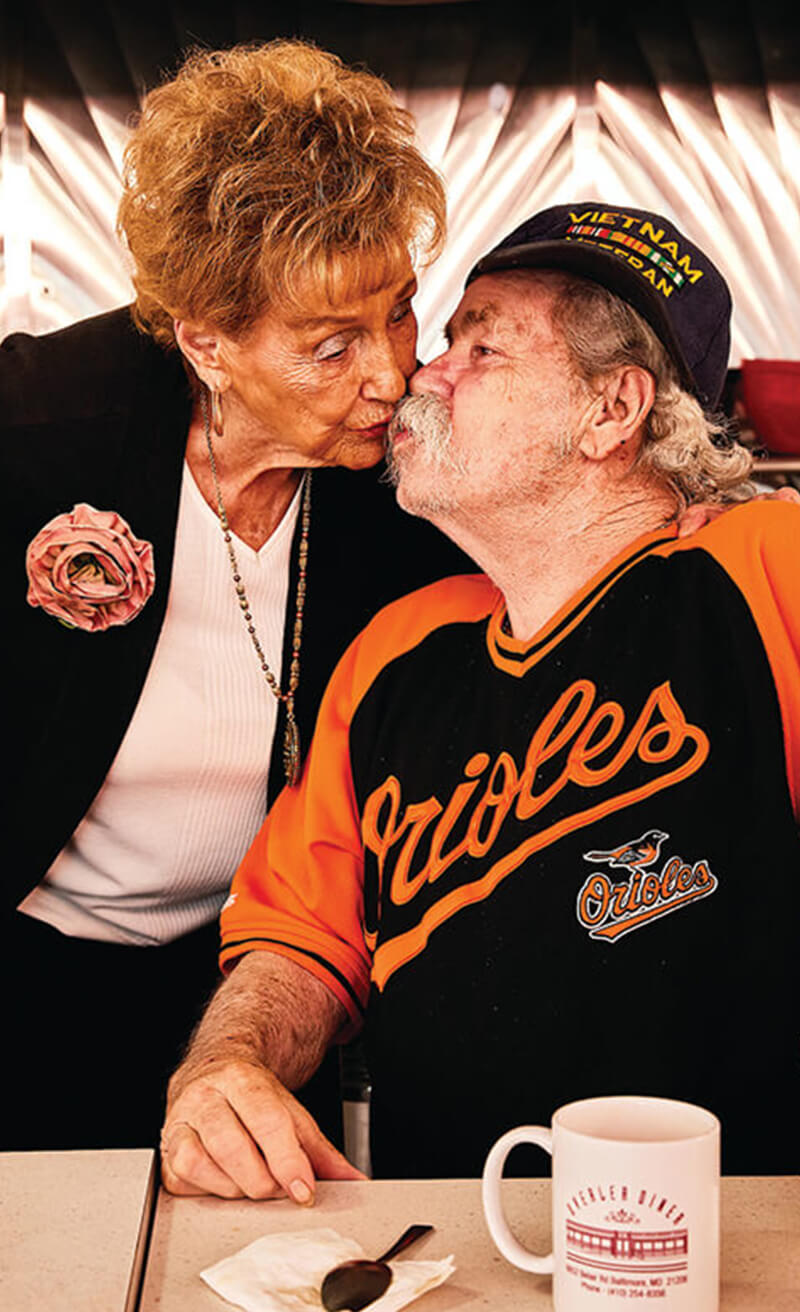

Above: A breakfast spread, chipped beef, Miss Betty and an O's fan, a row of counter stools, and empty coffee pots at Overlea Diner

OVERLEA DINER

Overlea

This is not a hipster diner, rather one filled with plenty of chrome and red Naugahyde booths, all of which have remained largely unchanged since the ’80s, when the place was rebuilt after the original 1946 wooden structure was destroyed by fire. Overlea was owned by the same Greek family until Tony Fonseca bought the business in 1995, taking over the same menu and drawing many of the same regulars who still frequent the place. Ninety-five-year-old Betty Kelly has been coming since 1950, when she moved into the neighborhood. For the last few years, she’s presided over a dozen regulars every Friday morning for breakfast. Kathy Lopez, an Overlea server for 14 years, serves them coffee and chipped beef (Miss Betty’s favorite). “I see them coming and line up their drinks,” says Lopez. There are daily specials (liver and onions, meatloaf, spaghetti and meatballs), and pie in the refrigerated case behind the counter next to the coffee pots. And, on Friday mornings, there are the name cards Lopez made for Miss Betty and her crew—many who show up in Orioles gear—waiting at their table, next to the jugs of maple syrup.

Slices of Heaven

Don’t forget dessert. From the earliest horsedrawn wagons that were the modern diners’ precursors to the chrome-and-neon behemoths beside our contemporary highways, diners have always had pie. Over the years, the pastry cases have expanded to include cheesecakes, cream pies, chocolate layer cakes, even Smith Island cakes. Broadway Diner in Canton will even bake your favorite dessert if it's not on their lengthy menu.

-

Cherry pie | $4.99 Towson Diner

-

Smith Island Cake |$5.99 Nautilus Diner

-

Red Velvet Cake |$7.95 EC Diner

-

French Apple Pie |$3.89 Double T Diner

-

Lemon meringue pie |$3.95 Boulevard Diner

-

Chocolate cream pie |$4.99 Towson Diner

-

Chocolate fudge cake |$7.95 EC Diner

-

Red velvet cheesecake |$7.00 Broadway Diner

-

Coconut custard pie |$3.89 Double T Diner

-

Cannoli cheesecake |$6.49 Nautilus Diner

*Prices by the Slice

Illustration by Disha Sharma

Scan a crowded counter at any Baltimore-area diner and you’ll likely see a walnut-colored rectangle, crisped into oblivion, adjacent to eggs-over-easy and a pile of home fries. This is scrapple—a pressed loaf of pig bits, cornmeal, buckwheat or wheat flour, spices, and plenty of salt—and it’s a Mid-Atlantic delicacy. It is old-school regional food, inherited from Pennsylvania Dutch, German, and Quaker farmers, and the object of deep nostalgia for folks who grew up eating the stuff, albeit mystifying for those who did not. It is our answer to Spam, originally made at home and on farms, these days mostly trucked in from Rapa, a 1926-founded Delaware company that is the world’s largest scrapple producer and supplies about three-quarters of the Baltimore area. Unlike Spam, which can be found in Korean Army soup, Hawaiian musubi, and trendy bakery pastries, scrapple is mostly found in the kind of breakfast joints that are as nostalgic as it is.

“It’s diner food,” says William Woys Weaver, whose book, Country Scrapple: An American Tradition, came out in 2003 and whose great-grandfather was in what Weaver describes as “the Quaker scrapple business” in Pennsylvania. “You know, 3 a.m. hot coffee and a slab of grease.” Indeed, scrapple, fried on a flattop until it is no longer gray but the color of 70-percent chocolate, does call for a pile of eggs and rye toast and a bottomless mug. This is not highbrow food, but a primitive kind of terrine built with German sausage-making skills and an abundance of Mid-Atlantic corn.

“Everybody wants scrapple with their eggs. It’s a Baltimore thing,” says Ray Crum, owner of both Pete’s Grille in Waverly and Werner’s, a diner that’s been in downtown Baltimore since 1950. Crum says the two restaurants go through seven cases of Rapa’s product a week. “It’s always been on the menu,” he says, “ever since I can remember.” And while diners serve the stuff mostly as a side, some have gotten a bit more creative, putting the scrapple into egg sandwiches or skillets. Honey Bee diner in Glen Burnie even has a scrapple wrap on the menu, with vegetables (gasp) and melted Swiss.

“Baltimoreans are creatures of habit,” says Weaver. “They’ve been doing this for 100 years, and so that’s the way you do it.” By which he means both the making and the consumption of scrapple. And although you can buy your own loaf of the stuff, it is perhaps best at a diner counter, fresh off the grill and bestowed by a server carrying a jug of strong java to wash it down.

Above: Taking an order, the exterior, local college crew, a waffle iron, and scrapple all at Pete's Grille.

PETE’S GRILLE

Waverly

Looking for pancakes in Baltimore? If you know, you know that means you’re heading to Greenmount Avenue and snagging a stool at Pete’s Grille. Look for the red brick building with black awnings, where breakfast is served all day, and for good reason. Available by the short stack or full stack, Pete's heaps of buttery hotcakes cooked to pillowy perfection on the flattop griddle, served with a sticky pitcher of syrup (and best eaten with a side of salty-sweet sausage links) are a bucketlist must in our fair city. If you’re still hungry, or craving something savory, forge ahead with an order of the creamed chip beef and hash browns. We especially love Pete’s for being a welcome crossroads of Baltimore, just a scramble from the 32nd Street Farmers Market, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and local colleges like Johns Hopkins, Loyola, and Morgan State.

SIP & BITE

Canton

With a two-story-tall red-haired waitress painted on the side of the rowhouse and a picture of Guy Fieri near the door, it’s hard to miss this Canton diner. Opened in 1948 by George Vasiliades, the place is now owned by his son, Tony, and Tony’s wife, Sofia, who took over the business in 2010. Inside, a long kitchen and counter run the length of one side; turquoise booths fill the other. Wallpaper featuring Edgar Allan Poe, the Domino Sugars sign, and Thurgood Marshall cover the walls, as well as another headshot of Fieri, who favored the diner’s crab cakes, which come in a variety of combinations, including softshell crab, steak, and spanakopita. There are plenty of other Greek dishes on offer among the traditional diner favorites. Yes, the crab cakes are very good. And yes, the servers call you “hon.” They’ll also regale you with stories of the old days, when the place would fill up with hungry drunks and drag queens after the nearby bars would close. Sip & Bite was open round-the-clock until the pandemic, but now closes at 3 p.m., and 7 p.m. on weekends. Maybe someday they’ll replace Fieri’s picture with one of Divine. One can hope.

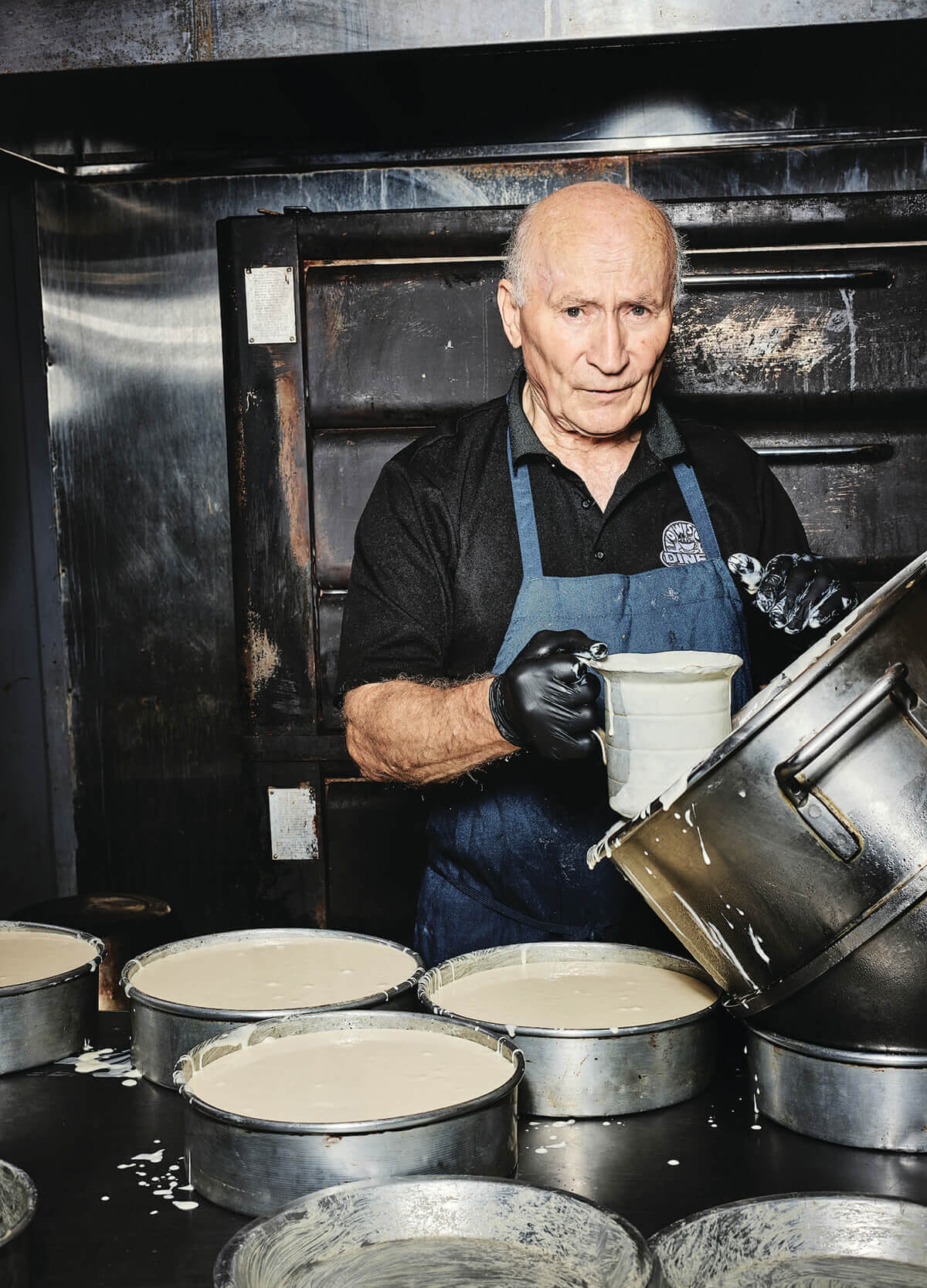

The tall pastry case at Towson Diner features a display of chocolate cakes, cream and fruit pies, strawberry shortcakes, turnovers, cheesecakes, pastry horns, eclairs, baklava, carrot cakes, and oversized chocolate-chip cookies. But what’s even more impressive than the contents of that case is 82-year-old Sam Kourtsounis, the man who bakes everything in it. These days he works three or four days a week, down from the seven that he often worked when he and his brother, Pete, bought the diner on a busy stretch of York Road in the early ’90s. A decade ago, Kourtsounis’ son Nick, a former Maryland state trooper, bought out his uncle and now spends his time running the place, while his father works the decades-old Blodgett deck ovens in the basement kitchens, rolling out dough for cherry pies and sliding trays of cheesecakes into the heat.

“BAKING IS ACTUALLY AN ART. IT’S COMPLICATED. WHEN YOU COOK, YOU CAN PLAY WITH IT. WITH THE BAKING, YOU CANNOT CHEAT.”

Kourtsounis immigrated to New York City when he was 14, arriving alone from Greece. After high school, he joined the Army, started a family, and began cooking in diners, mostly Greek diners that had full-scale bakeries. He and his brother bought their own diner on Long Island and then, some three decades ago, the family relocated to Towson and took over the Towson Diner, open since 1957. Over the years, Kourtsounis has collected recipes, which he keeps in a thick folder, some written in Greek on old guest checks.

“Baking is actually an art. It’s complicated. When you cook, you can play with it. With the baking, you cannot cheat,” says Kourtsounis, who bakes all the bread, including challah and the loaves for the diner’s popular French toast. Given the expense and the difficulty finding bakers, he notes that many diners don’t bake what he does anymore. “It’s like a dying art that you’re trying to keep alive,” says his son. “It has a history, and I don’t want that history to go away.” “Back in the ’60s, ’70s, every diner had a bake shop,” says Kourtsounis. “[I know] because I worked in them. A lot of the bakers, they retired. Some passed away.”

He’s been trying to teach some of the cooks he’s worked with. One got so frustrated, says Kourtsounis, that the young would-be baker would bang his head against the wall. “Others just don’t pick it up,” he says. Another issue, patron’s palates differ according to region. Kourtsounis now makes chocolate-chip cookies, apple pies, and lemon meringue pies instead of Black Forest cake, the layered, German gâteau preferred by New Yorkers. “It takes a lot of effort, but I can make everything that Yia Yia’s Bakery makes,” he says, smiling, referring to the popular Greek bakery in Rosedale.

Not only do diners have pies and cakes, but some have the ice cream sundaes, banana splits, and even egg creams of old-school soda fountains.

TAMBER’S RESTAURANT

Charles Village

“Diner food or Indian food?”—that is the question. Be warned, you might go to Tamber’s thinking you want a burger and a milkshake and end up ordering a chicken vindaloo and mango lassi. (Never underestimate the allure of the smell of Indian curry.) Either way, you can’t go wrong. Certainly the Indian food is superior—it rivals any white-tablecloth Indian spot in town. (In fact, we have a few Indian friends who maintain it’s the best in the town.) But from the chicken Parmesan to the meatloaf and turkey Reuben, the diner food has no business being as good as it is. That’s probably why the restaurant has been serving Hopkins students and professors, Charles Village-area residents, Union Memorial staff, and anyone else seeking a reasonably priced, friendly meal since 1992. (There’s an adjacent carry-out-only spot that serves the same food.) And by the way, nowhere is it written that you can’t get a side of French fries and a malted milkshake with your chicken tikka masala.

Above: The exterior at Towson Diner; Preparing food and the hot griddle at Pete's Grille; Goulash, French toast, and a corner booth at Towson Diner.

TOWSON DINER

TOWSON

A unknown on York Road with its neon sign (now LED) and stainless-steel exterior, this college student favorite, owned by the Kourtsounis family since the ’90s, dates to 1957. Inside, there are double booths equipped with CD jukeboxes, and diners peruse spiral-notebook menus set out on paper placemats filled with local advertising. Trusted favorites—a triple-decker turkey BLT club and the Bagel All the Way, with Nova Scotia lox and all the fixings—have a star next to them. That said, it’s hard to go wrong with the classics: sour beef and dumplings, crab cakes, and the Hungry Person Special, which includes two eggs, two pancakes, your choice of protein, and a side of home fries.

WERNER’S DINER

Downtown

There has been a long slow demise of diners in downtown Baltimore, from Hollywood Diner (used for Levinson’s Diner) on Saratoga Street, to Burke’s on Lombard and Light, tragically replaced by a Royal Farms. Now on Redwood Street, a short trip from the Harbor or The Block, Werner’s might be the last of its kind. Open since 1950, it’s a certain time warp where you can easily imagine the days when Sun workers, politicos, and shift workers all rubbed elbows over cups of hot coffee and plates of scrapple and eggs—and often enough, that’s still true. These days, it’s open every day but Saturday, usually as early as 7 a.m. Under new ownership (the same as Pete’s Grille in Waverly), there’s an expanded menu, still chock-full of standbys. We recommend grabbing a booth or linoleum two-top for a sky-high club sandwich and cup of Maryland crab soup.