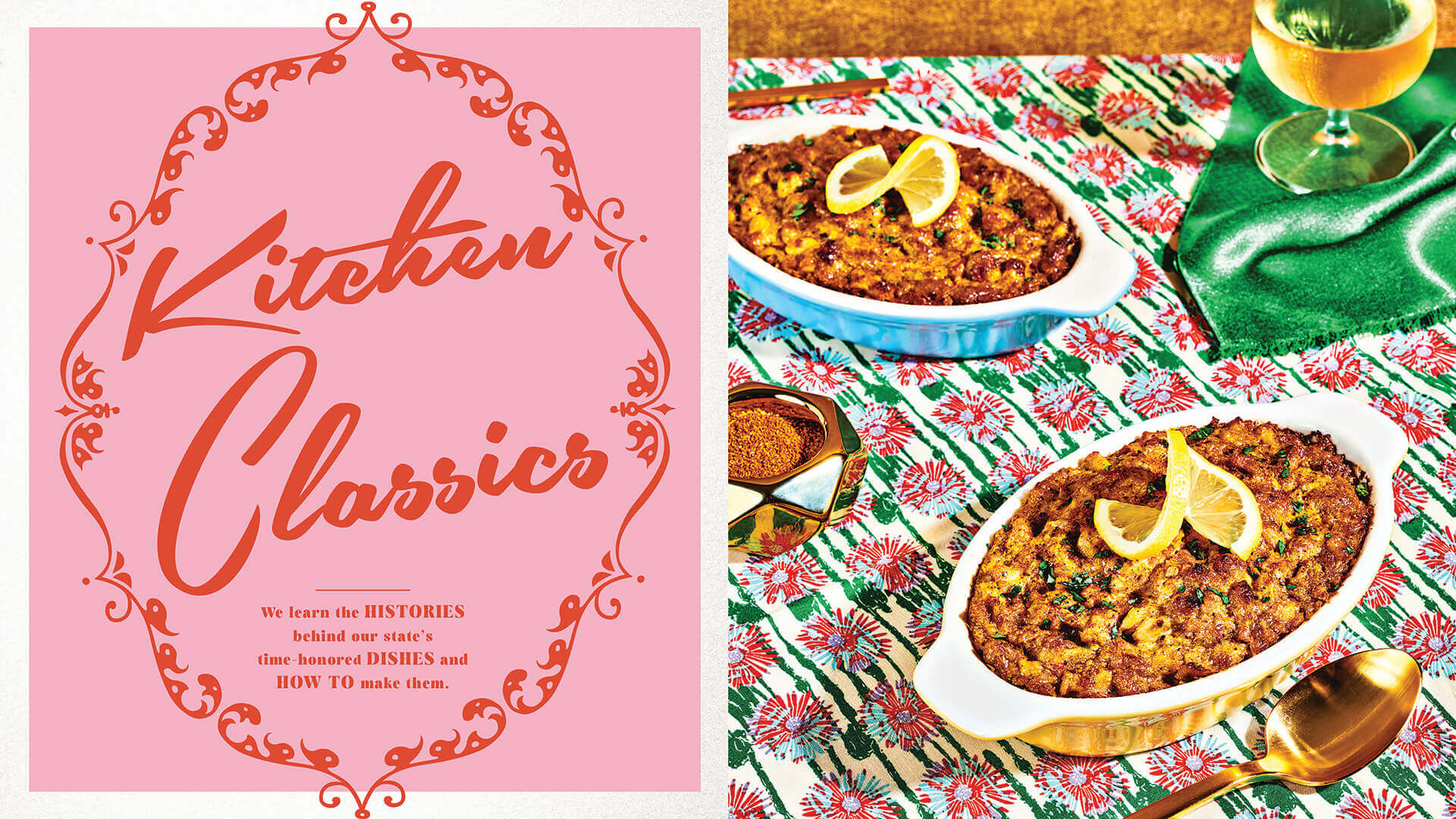

Food & Drink

We learn the histories behind our state's time-honored dishes and how to make them.

Edited by Jane Marion

with Suzanne Loudermilk and Lydia Woolever

Photography By Kate Grewal with Prop Styling By Kelsey Linehan

Illustrations by Disha Sharma

we Marylanders are crab cakes and coddies, pit beef and fried oysters. But when we start celebrating regional recipes in the Old Line State—with its fertile forests and fields, abundant estuary, and diversity of people—our culinary delights go way beyond the dishes that tend to attract all the attention. While largely lost to time and trends, there are so many lesser-known dishes from across our region—oyster stew, mock turtle soup, roast duck—that are no less delicious or distinct.

Maryland’s foodways are rich as the fudge—yes, fudge—invented here (see below), and equally bountiful for farmers, fishermen, and hunters alike. As Maryland boasts one of the most fertile ecosystems in North America, ingredients like tomatoes, pawpaws, wild berries, sorghum, and wheat have long grown—or been planted—here. (Of note, as a supplier of flour to the Continental Army in the 1600s, the Eastern Shore was dubbed the “breadbasket of the American Revolution.”) And Maryland was once the peach-and strawberry-growing capital of North America, and a place where figs—and even pomegranates—flourished.

As is still true today, our land is rife with wild duck, deer, rabbit, and muskrats that were roasted, fried, fricasseed, and stewed for centuries. Water-wise, the Chesapeake Bay, the largest estuary in North America, provided the protein for countless meals—from deviled crab to soft-clam pie and pickled oysters. In fact, the charms of the Chesapeake were noted not only by the Algonquins who dubbed the body of water “Chesapeake”—which translates to “at a big river”—but also by early colonists like Captain John Smith, who proclaimed that “heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation.”

“This was the little petri dish of American cuisine right here in the Chesapeake region, and in Maryland.”

— John Shields

Our local larder has always been a great natural resource for those who lived here. Indigenous people planted corn, beans, and squash, and their foodways were vital to our earliest survival; British colonists brought their penchant for porridges, puddings, and pies, and enhanced them with homegrown ingredients like peaches and apples; and enslaved Africans and their descendants spiced up their dishes with items like fish pepper, sweet potatoes, onions, and greens, forever influencing local flavors.

So how does one characterize Maryland cuisine? “There’s no one ethnicity that defines it,” says Annapolis-based food historian Joyce White, who recreates bygone regional dishes for her A Taste of History blog, as well as at historic sites like the Riversdale House Museum in Prince George’s County and the Hammond-Harwood House in Annapolis. “But if you’re looking for the foundations of early Maryland food history, it’s that combination of Native American, British American, and African American, all tied up together.”

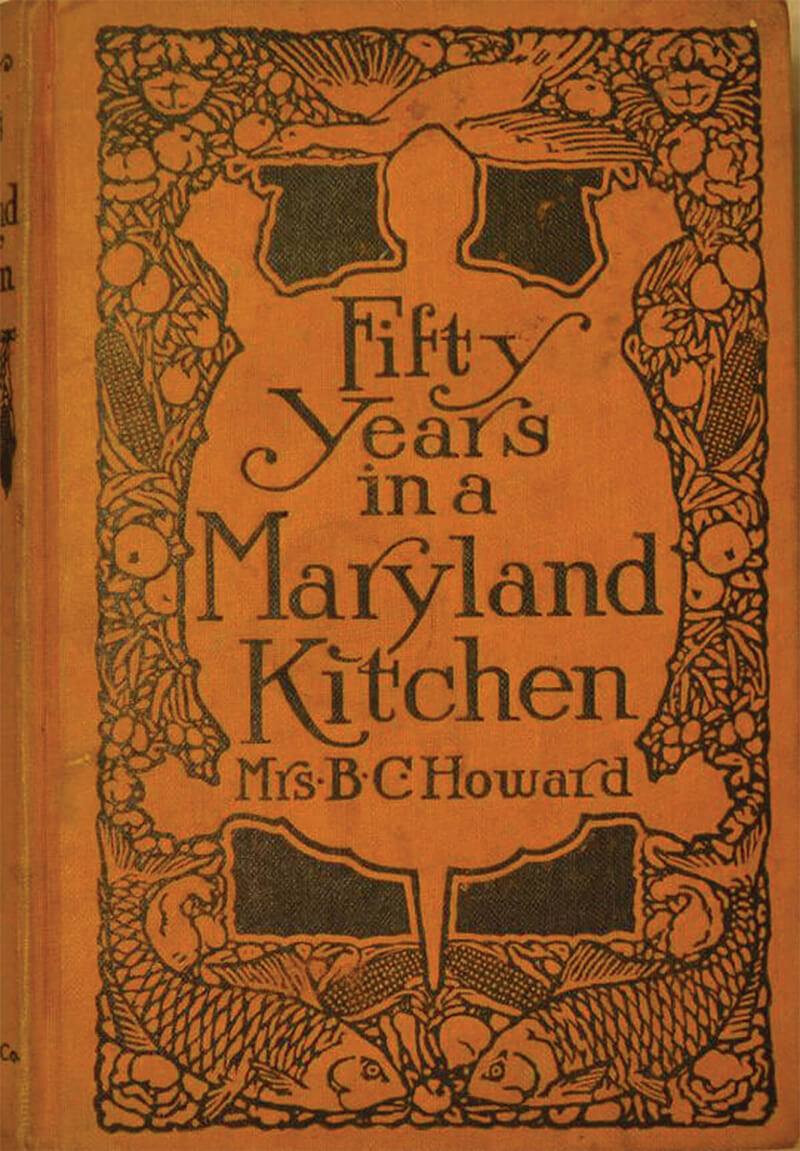

A collection of vintage Maryland cookbooks. Fifty Years in a Maryland Kitchen was first, published in 1873. It includes recipes for vanilla ice cream and beef à la mode.

The Mid-Atlantic was once the gastronomic heart of the “New World,” with our nation’s capital in nearby Washington, D.C. (and an even earlier iteration in Annapolis in 1783, when the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War was ratified there). “In the early days, when people came to the United States from around the world, they were tasting food from here and that became quintessential American food,” notes John Shields, owner of Gertrude’s Chesapeake Kitchen and author of Chesapeake Bay Cooking with John Shields.

“They were basically eating Chesapeake Bay fare.”

Given our political positioning, Thomas Jefferson would bring famed chefs from Europe to Annapolis to train his own cooks. (James Hemings, an enslaved cook at Jefferson’s Monticello, also travelled to Paris with the president to learn the French style of cooking.) “So, you have some classic European cooking techniques, but then they’re using the ingredients indigenous to our area,” says Shields.

“Enslaved people would bring their own traditions and ingredients into that mix, too. This was the little petri dish of American cuisine right here in the Chesapeake region, and in Maryland.”

As the state evolved, influenced by new influxes of immigrants from Italy, Germany, Ireland, and Eastern Europe, Mid-Atlantic cuisine became even more of a melting pot, as displayed in dishes that graced local tables such as veal stuffed with crabmeat and mozzarella, sour beef and dumplings, and Southern specialties like johnnycakes and pan-fried chicken in gravy.

James Beard Award-winning writer, culinary historian, and D.C. native Michael W. Twitty says that the influence of Black cooks in shaping not only Southern cuisine, but American cuisine, cannot be overemphasized. “The contribution of Black cooks is central,” says Twitty. “I want people to know we were bakers. We were pastry makers. We were chefs . . . we were all sorts of things that contributed to the culinary contributions and cuisine of Maryland and beyond.”

Thankfully, as a testament to those cooks, and countless others, many recipes remain—whether passed down orally, handwritten on recipe cards, compiled in community cookbooks, or published in classic tomes, like 300 Years of Black Cooking in St. Mary’s County Maryland, Mrs. Kitching’s Smith Island Cookbook, or Maryland’s Way. While the cooks who wrote many of these recipes—or “receipts,” as they were often called, both derived from the Latin verb recipere, meaning “to receive or take”—are long gone, their contributions live on.

Recipes offer us a “connection to our ancestors,” says White. “What we eat is such a visceral thing. We can’t ever recreate them 100 percent, because of different methods of producing flour and producing meat and all these things. But at the same time, it’s one of the only ways we really can have a shared experience with our ancestors.”

Below are a smattering of time-honored dishes that were once commonly cooked in Maryland kitchens, now brought into the 21st century, from chef David Thomas’ crab imperial to James Beard Award-winning author Steven Raichlen’s fudge. Bring the past to the present and recreate these forgotten flavors in your own kitchen.

Recipe for Success

A Remington resident pays homage to Maryland’s historical recipes.

By Jane Marion

ILLUSTRATION BY DISHA SHARMA

KARA MAE HARRIS stumbled upon the idea for Old Line Plate about a decade ago, while perusing her mother’s old The Southern Heritage Pies and Pastry Cookbook. “When I looked at the book, I was surprised to see Maryland in there,” says Harris, who works as a data assistant when she’s not researching Maryland cooking traditions. The first recipe she tried was Maryland White Potato Pie, sweetened with sugar and lemon juice, made during the leaner months before the summer harvest in the late 1800s. “I was making all the classic Southern pies—bourbon, pecan—and so I made the White Potato Pie.” Harris’ exploration led her to other vintage cookbooks including Maryland’s Way: The Hammond-Harwood House Cook Book, published in 1963, and Eat, Drink, and Be Merry in Maryland, published in 1932. Before long, her blog was born.

Her culinary adventures became such a passion that Harris soon found herself in the stacks at the Enoch Pratt Free Library or Maryland Historical Society, reviewing old news clippings and handwritten manuscripts, organizing the recipes into a database that includes everything from the mundane (pot roast in cider) to the strange (shad roe ravioli). To date, Harris has 47,000 recipes in her file, though she uses the word “recipe” loosely, tagging each with a disclaimer, as many have no measurements and no instructions (though they do offer household hints, such as how to remove stains from table linens and how to cure constipation).

From her treasure trove, Harris tests many of the recipes in the comfort of her own Remington home, where she keeps a collection of 200 Maryland cookbooks. Since starting her research, she has cooked some 300 dishes, many of which she shares online, finding some unlikely surprises along the way. “Recently, I made a sauce for rockfish, and I found the woman who wrote the recipe on the Eastern Shore in Kent County had been an aviator,” says Harris. “She, along with her son, pioneered the idea of flying produce directly across the bay to Baltimore before the bridge was built.”

Above all, Harris—one part scholar, one part detective, one part cook—wants to celebrate the people who gave rise to these recipes. “It’s about everyday people and the way different communities adopted new ingredients or new recipes,” she says. “Recipes are a contribution of a generation of hands, and there is no one inventor. For me, that’s the appeal.”

ALWAYS DRESS UP THE TABLE!

While johnnycakes are a seemingly simple recipe, their history runs deep, according to John Shields, owner of Gertrude’s Chesapeake Kitchen and the author of numerous books on the Chesapeake Bay. “Corn and cornmeal were a staple all around the Mid-Atlantic, and especially around the Chesapeake region,” says Shields. “As people came from Europe, they really hadn’t established wheat, but they learned about corn from the Native Americans.”

While Shields say the exact origin of this 18th-century breakfast staple is up for debate, references to johnnycakes (also known as Journey Cakes, cornpone, and hoe cakes) are found frequently in archives from the 13 colonies. “I found quite a number of recipes in Chesapeake regional cookbooks when researching he Chesapeake Bay Cookbook,” says Shields. “The cakes are a cornmeal flatbread that legend says had the name Journey Cakes, as the original recipe had no leavening and only boiling water as the liquid—nothing could spoil, thus they were perfect for a long journey. They didn’t taste great, but at least you wouldn’t starve.”

“The cakes are a cornmeal flatbread that legend says had the name Journey Cakes.”

Much like the dish’s name, which has many derivations—“Journey” sounded like Johnny in Southern dialect; or Shawnee, possibly a garbled reference to the Native American tribe that cooked the cakes—recipes for johnnycakes expanded and adapted over time. “It went from boiling water and corn, then they would start to mix flour and cornmeal because that lightened the texture,” says Shields. “The next thing that happened is that they would put an egg in. And as people became more affluent, they put milk in, and then it moved on to using a leavening agent. Eventually, that evolved into cornbread.”

Shields’ johnnycakes are a more modern (and far more delectable) version of those earlier iterations. “I add some corn kernels to give it a different texture,” Shields says. “At Gertrude’s, we will add smoked chipotle peppers to give it a different dimension, or a puréed roasted red pepper—there are so many ways to take the basic dish and then flavor it.”

How the cakes are consumed has changed over time, too, from a sustenance snack to more of a meal. “These johnnycakes can be served as a breakfast item with butter and syrup or honey,” says Shields, “or served as the foundation of a plate with shredded meat resting on top." —Jane Marion

JOHNNYCAKES

Chef John Shields

Serves 4 to 6

Ingredients

- 1 egg

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 1 ½ cups milk

- ½ teaspoon salt

- ¾ cups yellow cornmeal, stoneground

- ¼ cup all-purpose flour

- 1 tablespoon butter, melted

- 4 tablespoons bacon drippings or Liquid Smoke (if using vegetable oil)

Directions

Preheat the oven to 400 degrees Fahrenheit. Beat the egg and sugar together in a bowl. Stir in milk and salt. Beat in cornmeal and flour. Mix in butter and 2 tablespoons of bacon drippings (if using vegetable oil, add 2 drops of Liquid Smoke).

Generously grease an 8-inch cast-iron skillet with the remaining 2 tablespoons of bacon drippings. Place in hot oven for about 5 minutes. Remove from oven and pour in batter.

(Conversely, these can be made on a hot griddle into small individual cakes.) Return to oven and bake for 30-40 minutes, or until well-browned. Cut into wedges. Serve hot.

White Potato Pie

White potatoes were grown on the Eastern Shore in rotation with the more prized crop of tobacco. What to do with the surfeit of spuds? Mash them, add sugar, spice, eggs, butter, and pour them into a pie crust. Most recipes for white potato pie (also known as white potato pudding in a paste) resemble pumpkin or sweet potato versions. One of the earliest recipes was published in Baltimore in 1869 in a book called Domestic Cookery, Useful Receipts, and Hints to Young Housekeepers.

Smith Island Cake

This many-layered marvel was first founded in Eastern Shore church basements, and often concocted from boxes of cake mix. Legend has it that oystermen’s wives whipped up these towers of pancake-thin yellow cake, slathered with fudgy frosting, to fortify their husbands during the oyster season. The famed cakes, with as many as 10 layers, were anointed the “state dessert” on October 1, 2008.

Baltimore Peach Cake

Peaches were once bountiful in Baltimore. In The Sun, the first mention of peach cake—a semi-sweet, yeasted cake topped with sliced, locally grown peaches—goes back as far as 1884, when it was eaten at St. Michael’s Day in West Schuetzen Park, a beer garden in present-day Carroll Park frequented by German Americans. Recipes vary—glaze or no glaze, round vs. rectangular—but this seasonal dessert is undeniably scrumptious and still peddled at celebrated sweet shops, from Fenwick Bakery to Woodlea Bakery.

Schmierkäse

This cake was widely baked by German immigrants who came to Baltimore in the 1800s and is a rustic relative to cheesecake. Schmierkäse (or Smearcase Cheesecake) derives from the German words schmieren, to smear, and käse, for cheese. Though more modern recipes call for cream cheese, using cottage cheese was common in earlier days. Sprinkled with cinnamon, schmierkäse is lighter and less sweet than a traditional cheesecake, plus rectangular in shape with a cake-like crust.

Maryland Black-Walnut Cake

Thanks to the proliferation of black walnut trees along the Chesapeake Bay, the wood from these floral and fragrant nuts has been used locally in furniture-making, while the nuts themselves are folded into cookies and cakes. Though recipes vary, the cake’s closest kin is pound cake. It can be served simply dusted with confectioners’ sugar or enhanced with ice cream. Local black walnuts, with their thick-walled exterior, are a challenge to crack, which could explain why they’re no longer popular.

Hot Milk Cake

Made with scalded milk, this fluffy cake is a vanilla-scented cousin to sponge cake and can be made as a layer cake or in a tube pan. It was particularly popular during the Great Depression; when times were tough, and food needed to be stretched, the last drops of milk were sometimes used to make this treat. Believed to have originated in Chicago, the cake was commonly found in Chesapeake kitchens in the early 19th century when supplies were scarce.

MARASCHINO CHERRIES ADD A POP OF COLOR

It’s safe to assume that the bakers of Deal Island, Smith Island, and Tangier Island, Virginia, were competitive in the sweets department. Each Chesapeake Bay outpost has its own signature cake: Deal Island Devil Cream cake (aka Cream Devil cake), Smith Island cake, and pound cake, respectively. The Smith Island cake—Maryland’s official dessert—and pound cake may get more recognition throughout the state, but the Deal Island cake is revered in these shore counties for its moist chocolate cake and boiled white icing. Princess Anne resident Cindy Beauchamp, whose relatives grew up on Deal Island, makes the dessert any time “I take a notion to do it,” she says, using a recipe passed down by her great-great-grandmother, Cynthia Windsor Leonard, who lived on the Eastern Shore island and whose recipe lives on in House of Windsor, a Deal Island family cookbook.

“The cake is easy to make. The biggest challenge is making the icing.”

No one knows the cake’s origin, though one guess is that its name is linked to the area’s early days in the 18th century when, as a refuge for pirates and outlaws, it was called Devil’s Island. “The cake is easy to make,” Beauchamp says. “The biggest challenge is making the icing—you have to know when to stop beating the sucker.” The icing is a challenge, agrees Nancy Goldsmith, another shore resident. Even though she’s had a house in the area since 1975, she is still considered a “come here,” or someone who isn’t from those parts. But Goldsmith has made the cake’s promotion her mission. “There’s always been talk about Smith Island cake,” she says. “Why not Cream Devil Cake?” She once approached a Salisbury bakery and asked them to make the cake to sell commercially. They told her it was too hard. “I’m still disappointed,” she says. “It’s very worth sharing.” Cecelia Ottenweller, who lives in Houston, visited Deal Island a few years ago. “The community stays because they know each other,” she says. “Food is important to them.” Ottenweller was fascinated by the cake. “The cheat is to use a Duncan Hines devil’s food cake mix,” she says, “though the frosting takes effort.” The result is worth it, she confirms: “It is delicious." —Suzanne Loudermilk

DEAL ISLAND

DEVIL CREAM CAKE

Grandma Cynthia Windsor Leonard

Serves 12

Ingredients

- ½ cup boiling water

- 4 ounces sweet chocolate (Baker’s German’s sweet chocolate recommended)

- 1 cup butter

- 2 cups sugar

- 4 eggs, separated

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

- 2 cups flour

- 2 teaspoons baking soda

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 1 cup buttermilk

Icing

- 4 cups sugar

- 2 sticks butter

- 2 cups evaporated milk

- 2 teaspoons vanilla

Directions

Heat oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit.

In a large bowl, pour boiling water over chocolate to melt. Cool.

In a separate bowl, cream butter and sugar. Beat in egg yolks, then stir in vanilla and melted chocolate. Set aside.

Mix flour, soda, and salt together. Add flour mixture alternately with buttermilk to chocolate mixture. Beat egg whites until stiff peaks form, then fold into batter.

Pour batter into three buttered and floured 9-inch cake pans. Bake for 30 minutes or until a toothpick inserted in centers comes out clean. Cool. Frost with icing.

Icing

In a heavy saucepan, combine sugar, butter, and evaporated milk. Cook on medium heat about 15-20 minutes, stirring constantly. Remove from heat and add vanilla.

Tilt pan and beat for about 10 minutes until spreading consistency. Refrigerate for three hours. Makes enough icing to frost three cake layers. Note: Icing might have a slight yellow tinge.

VINTAGE PLATES ADD TO THE VIBE

You have to drive awhile to find it—away from the cities, down tiny two-lane highways, along the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. Only in Southern Maryland can you sate yourself on stuffed ham, and many would argue that the real deal only exists in the sliver of St. Mary’s County, some 70 miles south of Baltimore. Here, this hyperlocal delicacy is a source of great pride—a go-to for holiday suppers, county fair cook-offs, and church fundraisers, with every family perfecting their own recipe over multiple generations.

“It’s just such a neat tradition that has carried weight for such a long time in such a small place.”

Despite the differences, it all boils down to a whole fresh ham, corned in salt, stuffed and covered with several pounds of cabbage and other fixings like kale, onion, black and red pepper, and seasonings like mustard and celery seeds, depending on the cook. From there, it’s wrapped in anything from cheesecloth to pillowcases and T-shirts, boiled for several hours, cooled in a fridge or on a back porch, then sliced cold, served alone or sandwiched. Condiments are sacrilege.

“It is at least a three-day process to do this properly,” says chef Zack Mills of True Chesapeake Oyster Co. in Whitehall Mill, which has its own aquaculture farm on St. Jerome Creek in St. Mary’s County. “My first introduction was by means of an argument between two locals—over whether or not kale goes into it. I was immediately intrigued and read probably 30 recipes, from historic cookbooks to the internet to people down at the farm, and molded them together into a greatest hits version.”

Like many an old recipe, stuffed ham’s origins are elusive, perhaps dating as far back as the 16th century. It's akin to age-old British recipes, including a childhood favorite of Lord Baltimore, but food historians lean toward its Afro-Caribbean roots, likely hailing from the local enslaved population, who were also tasked with making the beaten biscuits that were often served as an accompaniment. Today, the dish remains a ritual in Black and white households, cooked at home and purchased at local country stores, where it now tops everything from egg rolls to pizzas. “It’s just a neat tradition that has carried weight for such a long time in such a small place,” says Mills, who loves its charcuterie-like flavor profile—salty, subtly sweet, a hint of piquant bitterness and warm spice. “That’s pure family-recipe love to me." —Lydia Woolever

TRADITIONAL STUFFED HAM

Chef Zack Mills

Serves 15-20

Ingredients

- Roughly 10 pounds ham (fresh or corned)

- 3 pounds green cabbage

- 1 pound kale

- 1 pound yellow onion

- 1 tablespoon kosher salt

- 2 tablespoons whole black peppercorns

- 2 tablespoons red pepper flakes

- 1 tablespoon mustard seed

- 1 tablespoon celery seed

Directions

Remove bone. Rinse ham under cold water and pat dry. Place ham on a tray and season with salt to coat. Place in non-reactive container, preferably with a resting rack between the ham and the bottom. Cover with plastic wrap. Refrigerate 5 days or up to one week. Every two days, unwrap ham, drain excess liquids, salt and refrigerate.

Once ham is corned, remove from container and rinse off salt. Place on clean tray and pat dry.

Rinse cabbage, kale, and onions, remove any stems, and finely chop all vegetables. Place into mixing bowl, season with salt. Mix to combine. Coarsely grind peppercorns, red pepper flakes, mustard and celery seeds. Add seasoning to vegetables and mix.

Place corned ham on cutting board. Butterfly from the seam to lay flat.

Place a cheesecloth, twice the size of the ham, on a clean work surface. Place ham on top of cheesecloth. Pack stuffing down middle, placing it in the same direction as grains of ham. Roll one end of ham around stuffing to the other end. Coat outside with excess stuffing and wrap with cheesecloth. Tie with twine in several places. (Rinse ham first if you’ve cured it yourself.)

Fill a large, at least 4-gallon pot with cold water and boil, then submerge ham. Simmer and cook for 15 minutes per pound or until the meat’s internal temperature reaches 165 degrees. While cooking, skim impurities that rise to the top of the water.

Remove pot from heat. Once at room temperature, refrigerate ham in its liquid for at least 12 hours. If your refrigerator is not large enough, place the ham and liquid in cooler, add ice, and place outside. Once ham has fully cooled, remove from liquid and pat dry. Cut away cheesecloth. Slice and serve.

From opening Spread

In Maryland, where crab is already king, you have to be a pretty impressive dish to earn the moniker “crab imperial.” Tossed with mayonnaise, red peppers, seasoned with spices, and topped with breadcrumbs (plus Smithfield ham in tidewater Virginia versions), crab imperial is the fancier casserole cousin to the more-configured crab cake. Where did this decadent dish originate? Baltimore culinary lore has it that in the late 19th century, Thompson’s Sea Girt House, originally in Canton, was the first place to serve crab imperial, a concoction of backfin crabmeat swimming in a thick cream sauce. (Onions, green bell pepper, and pimento cheese were likely added later.) “Most dishes are usually inspired by previous dishes,” says culinary historian Joyce White, who points to the potential tie between crab imperial and deviled crab. “There’s a long history of crab and lobster being served in their shells in rich sauces. These date back to 17th-century Europe, and likely even earlier—at most, an old recipe was tweaked and given a new name.”

“. . . the recipe is a derivative of the deviled crab, which can be traced back to West Africa.”

While creamy seafood dishes may have fallen out of fashion, this recipe by chef David Thomas of the H3irloom Food Group is sure to bring at least one of them back. Thomas’ crab imperial was adapted from a recipe found in The Book of Lost Recipes from Harvey’s, a pre-Civil War restaurant originally in Washington, D.C., known as “the restaurant of the presidents” and a favorite of F.B.I. director J. Edgar Hoover. While doing research for his work on foods of the African diaspora, Thomas became fascinated by the history of Harvey’s and its significance in Black American history. “The menu drove me to dig deeper into the recipes,” he says. “Crab imperial was first served in a restaurant here in Baltimore, and the recipe is a derivative of the deviled crab, which can be traced back to West Africa.” Topping the dish with corn crumbs, while not typical now, is likely the way it was prepared in the past. “Corn and wheat were both grown here in Maryland,” says Thomas. “However, wheat was an expensive product. Corn was abundant and used to feed livestock and the enslaved. So, it stands to reason that cornbread, not wheat bread, was more prevalent in the recipe.” Thomas works to shine light on the contributions of African Americans to the country’s culinary canon as a means of broadening our understanding. “The Harvey represents an industry that was created by the enslaved working in the finest homes of the time,” he says. “The Harvey, like all restaurants from then through Jim Crow and beyond, wouldn’t allow African Americans to dine in but would exploit their talents and intellectual property. I always say that our path forward requires us to look back." —Jane Marion

NEW MARYLAND

CRAB IMPERIAL

Chef David Thomas

Serves 4

Ingredients

- 2 teaspoons butter

- 1 tablespoon small onion, diced

- 1 tablespoon small red pepper, diced

- 2 tablespoons Old Bay

- ½ cup mayonnaise

- 1 tablespoon Worcestershire sauce

- ¼ teaspoon yellow mustard

- 1 cup lump crab meat

- 2 ½ teaspoons cornbread crumbs

Directions

Preheat oven to 400 Fahrenheit.

In a small skillet, add 1 teaspoon of butter over low heat. Add onion and red pepper, sauté for 2-3 minutes on medium to high heat. Sprinkle with 1 tablespoon Old Bay and let cool.

In a bowl, mix all wet ingredients, minus remaining butter. Fold in crab meat and cornbread crumbs.

Place mixture in small oven-safe vessels, top with remaining Old Bay and remaining butter. Bake uncovered for 20 minutes or until golden brown.

TOP WITH WALNUTS FOR EXTRA CRUNCH!

The next time you whip up a batch of fudge, you might want to thank a 19th-century Baltimore grocer for the chocolate confection. The shopkeeper, who was selling the candy for 40 cents a pound at 279 Williams Street, so the story goes, shared the recipe with a cousin, who passed it on to a Vassar College schoolmate, Emelyn Hartridge. Hartridge, in turn, started making fudge on the New York campus for a school auction in 1888, leading to its spread to other women’s colleges and eventually around the country. She later told a professor, “Fudge, as I first knew it, was first made in Baltimore,” according to a letter in the Vassar archives. Food historian John F. Mariani also points to her words in The Dictionary of American Food and Drink, leading him, too, to believe that fudge originated in Charm City.

Elmer Wengert, who has been a candymaker at Rheb’s Candies in Southwest Baltimore for 41 years, can’t confirm the origin of fudge, but he says one of the company’s old cookbooks has a recipe for Baltimore-style fudge, specifically. “It’s a hard-grained fudge, not like the creamy fudge we make,” he says, before adding: “We didn’t care for it.” Rheb’s has been making fudge since 1917 when its founder Louis Rheb decided to mix up sweet treats in his home basement to sell at local markets. Today, fudge isn’t always available at Rheb’s, but when Wengert has time, he will stir up batches of the confection with a big wooden paddle, turning out flavors like chocolate, vanilla peanut butter, and sometimes marshmallow. James Beard Award-winning cookbook author Steven Raichlen prefers homemade fudge, specifically the version his grandmother made when he was growing up in the Sudbrook area of Baltimore County.

“It was super simple. It was very dark chocolate, a serious fudge, firm and waxy in a good way.

Raichlen, who now lives in Miami and Martha’s Vineyard, says, “There was only one fudge—Grammie Ethel fudge.” He recalls mixing the ingredients for the candy at his grandmother’s Mt. Washington home in a now-nearly centuryold pie pan she had been using for the process since she was a newlywed. “It was super simple,” he says of the recipe, which includes sugar, milk, unsweetened chocolate, butter, and vanilla. “It was very dark chocolate, a serious fudge, firm and waxy in a good way. It brings back such good memories.” —Suzanne Loudermilk

FUDGE

Grammie Ethel Raichlen

Yields: 18-20 pieces

Ingredients

- 1 ¼ cups sugar

- ¾ cup whole milk

- 4 ounces unsweetened chocolate (Baker’s recommended)

- 5 tablespoons salted butter, cut into ½-inch slices

- 1 ½ teaspoons vanilla

Directions

Bring sugar and milk to rolling boil in a heavy saucepan over high heat. Boil until sugar is dissolved, about 2 minutes. Remove pan from heat and stir in chocolate with a wooden spoon. Return to heat and cook until chocolate is completely melted, stirring often. Boil mixture 2 minutes. Stir in butter and vanilla. Reduce heat to medium and cook fudge at slow boil until thick and bubbly, 15-20 minutes. Mixture should be the consistency of caramel, and butter should be just beginning to separate out into shiny beads.

Remove pan from heat and beat fudge until slightly thickened (it should be the consistency of soft ice cream). Do not overbeat or fudge will turn crumbly. Spoon fudge into lightly oiled 8-inch pie pan. Cut into squares while still warm.

GARNISHES ADD EYE APPEAL

On October 10, 1909, an unnamed bartender in the Sun paper declared a new cocktail game in town: “There was a drink started about a year ago which, I am told, is a big success in a number of other cities now. It’s called a frozen rye, and they tell me it’s an awfully smooth drink.” On this Sunday morning in Baltimore, it was still about a decade until Prohibition, and at the time, rye whiskey was to the Old Line State as bourbon is to Kentucky. At the turn of the 20th century, Maryland had become a hub of rye production, thanks to the region’s high grain yields and influx of Scotch-Irish immigrants, who brought with them their knack for distilling strong spirits. In 1911, there were some 44 distilleries across the state, half of which were in Baltimore, producing millions of gallons of rye, which was revered for its supposedly distinct style. “The most healthful appetizer yet discovered by man,” declared the Baltimore Bard, H.L. Mencken.

“The most healthful appetizer yet discovered by man.”

—H.L. Mencken

This was not long after inventive bartending, paired with the invention of commercial ice, gave rise to the American cocktail, and with it, the frozen rye. A complex mix of rye, curaçao, and other citrus juices served over fine-crushed ice in a Champagne glass, it was served at hotel bars like The Belvedere, where afternoon “tea parties” devolved into bacchanalian, day-drinking dance parties. During Prohibition, it was sloshed between ex-pats at cafes in Paris, and after Repeal Day, records show it lived on in nightclubs on Pennsylvania Avenue and country clubs in the county.

“It’s classic—a little unwieldy but quite refreshing, and not quite as sweet as you’d think—a nice summer drink,” says Gregory Priebe, who co-wrote Forgotten Maryland Cocktails: A History of Drinking in the Free State, with his wife, Nicole, first discovering the concoction on a 1966 Haussner’s menu framed in his mother's kitchen. “I would always look at it and think, ‘What the hell is a frozen rye?’”

In fact, few places can truly tell you, with Priebe’s vague version hailing from the lone recipe he could get his hands on, via a 1910 beverage distributor catalogue. By the mid-20th century, the frozen rye had fallen out of fashion, and it has since gone the way of a white-labeled bottle of Pikesville Supreme.

“The newspaper stories whet your appetite but don’t include the essential details that we need,” says Priebe of the cocktail’s long-lost recipe. “We’ll never know! But most drinks, you don’t. There should be an asterisk next to every origin story: Historian David Wondrich says cocktail history is history agreed upon in a bar.” —Lydia Woolever

THE BELVEDERE FROZEN RYE

Historians Gregory and Nicole Priebe

Serves 1

Ingredients

- Juice of half a lime

- Few dashes orange juice

- Few dashes pineapple syrup

- Few dashes orange curaçao

- Rye whiskey

- Garnishes: 1 slice orange, 1 slice pineapple

Directions

Fill Champagne coupe with fine ice and pour ingredients overtop. Garnish with fruit, allowing slices to stick out over top of glass.

New Old Favorites

Six ways to protect our natural treasure.

SHAD ROE: The word ”delicacy” gets thrown around often, but few dishes rival the status of this fleeting rite of spring—shad roe. Once the caviar of the Chesapeake and a historic highlight on fine-dining menus, the sautéed fish eggs

are a rich, love-it-or-hate-it dish, appearing in two fat lobes known as ”sets” that are enough to turn off a few eaters. But

inside, a delicate, flavorful dining experience awaits, with traditional recipes calling for shad to be sautéed in butter and

bacon or baked over a hardwood plank. A native river herring, the American shad was once the king of the Chesapeake—a

staple for Native Americans and early colonists, and fuel for American soldiers through the Revolutionary War. Eventually

it became the most valuable finfish of its day, with millions upon millions of the tiny silver slivers migrating up and down

these tributaries. These days, the shad we eat comes from out of state, as overfishing caused the Maryland season for this

once-prolific fish to shutter in 1980, followed by Virginia in 1994.

SHAD ROE: The word ”delicacy” gets thrown around often, but few dishes rival the status of this fleeting rite of spring—shad roe. Once the caviar of the Chesapeake and a historic highlight on fine-dining menus, the sautéed fish eggs

are a rich, love-it-or-hate-it dish, appearing in two fat lobes known as ”sets” that are enough to turn off a few eaters. But

inside, a delicate, flavorful dining experience awaits, with traditional recipes calling for shad to be sautéed in butter and

bacon or baked over a hardwood plank. A native river herring, the American shad was once the king of the Chesapeake—a

staple for Native Americans and early colonists, and fuel for American soldiers through the Revolutionary War. Eventually

it became the most valuable finfish of its day, with millions upon millions of the tiny silver slivers migrating up and down

these tributaries. These days, the shad we eat comes from out of state, as overfishing caused the Maryland season for this

once-prolific fish to shutter in 1980, followed by Virginia in 1994.

OYSTER PIE: Oyster pie isn’t indigenous to Maryland, with versions following the bivalve from New England to the Gulf and across the Atlantic.

But here in Maryland, we do know that this savory dish, with its flaky crust filled with seafood, vegetables, butter, and

seasonings, has been around for centuries, dating at least back to 1811, when it was apparently served at banquet

dinners at the Sotterley Plantation in Southern Maryland. A staple of regional cookbooks, sometimes referred to as

“pye,” it is a byproduct of the Chesapeake’s once-abundant oyster populations—an act of resourcefulness during the

lean months of winter, as well as comfort-food decadence, often served at the Thanksgiving table. H.L. Mencken used

to devour it at the famous Rennert Hotel on Liberty and Saratoga Streets. In a 1913 Sun column, he waxed rhapsodic

about the already disappearing Maryland treasure: “The oyster potpie is still a poem and a passion, a dream and an

intoxication, a burst of sunlight and a concord of sweet sounds...above all other potpies under the sun.”

OYSTER PIE: Oyster pie isn’t indigenous to Maryland, with versions following the bivalve from New England to the Gulf and across the Atlantic.

But here in Maryland, we do know that this savory dish, with its flaky crust filled with seafood, vegetables, butter, and

seasonings, has been around for centuries, dating at least back to 1811, when it was apparently served at banquet

dinners at the Sotterley Plantation in Southern Maryland. A staple of regional cookbooks, sometimes referred to as

“pye,” it is a byproduct of the Chesapeake’s once-abundant oyster populations—an act of resourcefulness during the

lean months of winter, as well as comfort-food decadence, often served at the Thanksgiving table. H.L. Mencken used

to devour it at the famous Rennert Hotel on Liberty and Saratoga Streets. In a 1913 Sun column, he waxed rhapsodic

about the already disappearing Maryland treasure: “The oyster potpie is still a poem and a passion, a dream and an

intoxication, a burst of sunlight and a concord of sweet sounds...above all other potpies under the sun.”

CODDIES: At certain seafood restaurants in Baltimore, we’ll skip the jumbo lump and go straight for the poor man’s

crab cake: the coddie. As late local raconteur Gilbert Sandler once put it, if you don’t know what a coddie is, “You are from

out of town, you are young, or you have been living in a cave.” An underdog delight dating back to the early 20th century,

this fried fish ball is a combination of salt cod, mashed potato, and a few shakes of spice, served between two Saltine crackers

with a side of yellow mustard. The coddie is said to have been invented in the local Jewish community in the early

1900s by Fannie Jacobson Cohen. She sold them at the Belair Market stall for 5 cents a-piece, which eventually led to the

family’s coddie-toting food-truck empire, which ran until 1971. A few can still be found today at restaurants like Faidley’s

Seafood, Dylan’s Oyster Cellar, Attman’s Deli, and Mama’s on the Half Shell.

CODDIES: At certain seafood restaurants in Baltimore, we’ll skip the jumbo lump and go straight for the poor man’s

crab cake: the coddie. As late local raconteur Gilbert Sandler once put it, if you don’t know what a coddie is, “You are from

out of town, you are young, or you have been living in a cave.” An underdog delight dating back to the early 20th century,

this fried fish ball is a combination of salt cod, mashed potato, and a few shakes of spice, served between two Saltine crackers

with a side of yellow mustard. The coddie is said to have been invented in the local Jewish community in the early

1900s by Fannie Jacobson Cohen. She sold them at the Belair Market stall for 5 cents a-piece, which eventually led to the

family’s coddie-toting food-truck empire, which ran until 1971. A few can still be found today at restaurants like Faidley’s

Seafood, Dylan’s Oyster Cellar, Attman’s Deli, and Mama’s on the Half Shell.

MARYLAND FRIED CHICKEN: The history of Maryland fried chicken is vague, but as early as 1887, a scribe

praised the dish in The Baltimore Sun, writing, “Its fried chicken is a dream.” Curious about its origins, The Evening

Sun staff set out on a mission in 1926 to find out who first made the battered poultry. They were unsuccessful, though

food historians believe enslaved cooks likely had something to do with its beginnings. At first, “Maryland” wasn’t even

attached to the dish’s name, which also became known as Maryland chicken and other variations of the name. In the

1873 cookbook Fifty Years in a Maryland Kitchen, it’s called “Fried Chickens.” And in the 1932 Eat, Drink & Be Merry

in Maryland, it’s titled “Southern Fried Chicken.” But one thing is constant——the cooking method. Chicken pieces were

dredged in flour and fried in hot lard, preferably in a cast-iron skillet with a lid, and served with creamy gravy. John

Shields says covering the pan “is a signature part of this particular dish.”

MARYLAND FRIED CHICKEN: The history of Maryland fried chicken is vague, but as early as 1887, a scribe

praised the dish in The Baltimore Sun, writing, “Its fried chicken is a dream.” Curious about its origins, The Evening

Sun staff set out on a mission in 1926 to find out who first made the battered poultry. They were unsuccessful, though

food historians believe enslaved cooks likely had something to do with its beginnings. At first, “Maryland” wasn’t even

attached to the dish’s name, which also became known as Maryland chicken and other variations of the name. In the

1873 cookbook Fifty Years in a Maryland Kitchen, it’s called “Fried Chickens.” And in the 1932 Eat, Drink & Be Merry

in Maryland, it’s titled “Southern Fried Chicken.” But one thing is constant——the cooking method. Chicken pieces were

dredged in flour and fried in hot lard, preferably in a cast-iron skillet with a lid, and served with creamy gravy. John

Shields says covering the pan “is a signature part of this particular dish.”

SOUR BEEF & DUMPLINGS: Baltimore’s beloved German restaurants might have folded over the years—think

Haussner’s and Eichenkranz—but iconic dishes like sour beef and dumplings and sauerkraut live on, an homage to a time

when German immigrants made up a large portion of the city’s population. One of the first local recipes appeared in The

Evening Sun in 1935 when a reader shared her formula: rump beef, covered with water and vinegar overnight, then cooked,

at which point a key ingredient—gingersnaps—was added. If the concoction sounds like sauerbraten, it is. But the German

American immigrants translated the name in appreciation of their new home. Today, you can find it on the menu at Johnny Dee's in Parkville and at Zion Church of the City of Baltimore, where it's served at an annual October dinner. Sauerkraut

is another German mainstay in Baltimore, especially on Thanksgiving. As chef John Shields writes in Chesapeake Bay

Cooking, “The absence of sauerkraut when turkey is present... is unthinkable.”

SOUR BEEF & DUMPLINGS: Baltimore’s beloved German restaurants might have folded over the years—think

Haussner’s and Eichenkranz—but iconic dishes like sour beef and dumplings and sauerkraut live on, an homage to a time

when German immigrants made up a large portion of the city’s population. One of the first local recipes appeared in The

Evening Sun in 1935 when a reader shared her formula: rump beef, covered with water and vinegar overnight, then cooked,

at which point a key ingredient—gingersnaps—was added. If the concoction sounds like sauerbraten, it is. But the German

American immigrants translated the name in appreciation of their new home. Today, you can find it on the menu at Johnny Dee's in Parkville and at Zion Church of the City of Baltimore, where it's served at an annual October dinner. Sauerkraut

is another German mainstay in Baltimore, especially on Thanksgiving. As chef John Shields writes in Chesapeake Bay

Cooking, “The absence of sauerkraut when turkey is present... is unthinkable.”