Food & Drink

Baltimore’s Love Affair With Petit Louis Bistro Has Been Going on for 20 Years—and Counting.

ON A LATE WINTER’S NIGHT at Petit Louis Bistro in Roland Park, an army of flame-licked All-Clad and Bourgeat pots and skillets are lined up as Chris Scanga gives verbal commands to the line cooks and two sous chefs working swiftly to fill orders across three ranges, a gas grill, and deep fryer.

Mussels get sautéed with garlic and herb butter. An omelet is filled with roasted tomatoes. Scallops are seared, then paired with poached lobster in cream sauce. Matchstick frites get dropped in the fryer. Crocks of onion soup are capped with inch-thick slices of gruyère, then placed in the 650-degree Vulcan oven for maximum melting.

“Pick up: one scallops, two trout, one quiche. Order pick up: Un cassoulet, por favor,” he calls out to his mostly Spanish-speaking staff. “Order up: Steak frites, well-done.” He juggles the onslaught with complete calm, as servers, runners, and the maître d’hotel bustle around him. Scanga takes his role of executive chef at Petit Louis, a position he has held for six years, seriously. “It’s a responsibility working here at a place that people consider an institution,” he says. “People will say ‘that’s the best onion soup I’ve ever had,’ or ‘that’s the best meal I’ve ever had’—that’s the reason I do it.”

Tony Foreman and Cindy Wolf in the dining room at Petit Louis.

This was the scene in the second week of March, which is to say what feels like a million years ago, before the coronavirus arrived—only four days later to be exact—and shut down the restaurant for 10 weeks before it reopened for carryout, and, eventually, patio and limited-capacity dining.

And while the reopening has brought along with it the new staples of contemporary dining—temperature checks, contact tracing forms, masks (blue, white, and red-striped for the servers), and an en plein air tented patio—its essence as a beloved bastion endures.

“One of the things that [co-owners] Tony [Foreman] and Cindy [Wolf] both deserve credit for is the way they’ve served during the pandemic,” says Roland Park resident and customer of 20 years Peter Bain, who frequents the restaurant so often that he can recite the nightly plat du jour and seasonal specials. “They’ve worked really hard to take care of their people and take care of their patrons. They’ve been very creative about setting up outside dining and takeout orders, and they’ve jumped through so many hoops to continue to be creative during this period—it’s one thing to be great under normal conditions, it’s another thing to be great in crisis conditions. They’re proving again that they’ve redefined standards and raised the bar for dining in Baltimore—and they’ve been doing that for decades.”

The tone was set with an inspired slogan that remains part of the restaurant's branding today: “IT's Fun! It's French!”

Clockwise from top left: Chef Chris Scanga in the kitchen; the steak frites; the main dining room; a seasonal salmon dish.

ome 20-plus years ago, Petit Louis Bistro—on the site of an 1897-era Tudor-style building developed by the then British-owned Roland Park Company, which has the distinction of being the country’s first strip mall—was just a gleam in Tony Foreman’s eye. When he caught wind that “The Morgue”—that is, the location of former neighborhood hotspot Morgan Millard—was going to be available for rent for the first time in 95 years, he fantasized about opening a French bistro in the space, though Wolf (his wife at the time) was less gung-ho initially. “Cindy didn’t want to do a second restaurant,” says Foreman. “We had just opened Charleston, but I just kept pushing her on the idea.”

But on a 1998 trip to Paris, Wolf had a change of heart. The duo wandered into Chez Louis L’Ami for a meal at the proper French bistro founded in 1924 on a little side street in the 3rd arrondissement of the Northern Marais district. A meal of foie gras terrine, a stack of warm toast, and a bottle of Sauternes showed them the epitome of what food could aspire to be. “Ahhhh,” recalls Wolf, looking starry-eyed at the memory. “It was the most decadent thing I’d ever seen. I couldn’t believe how opulent it was—it was so exciting. And for me as a chef, getting to see this 1920s bistro, it felt very, very old, and authentic.”

Empty wine bottles sit in the window.

Wolf’s enchantment with the bistro had been Foreman’s plan all along. “I’d been trying to figure out how to do it, and it made it a whole lot easier to convince her with a glass of Sauternes and a little stack of foie gras terrine slices and the warm toast,” says Foreman, laughing. “You’ve got to know your audience when you’re selling something.”

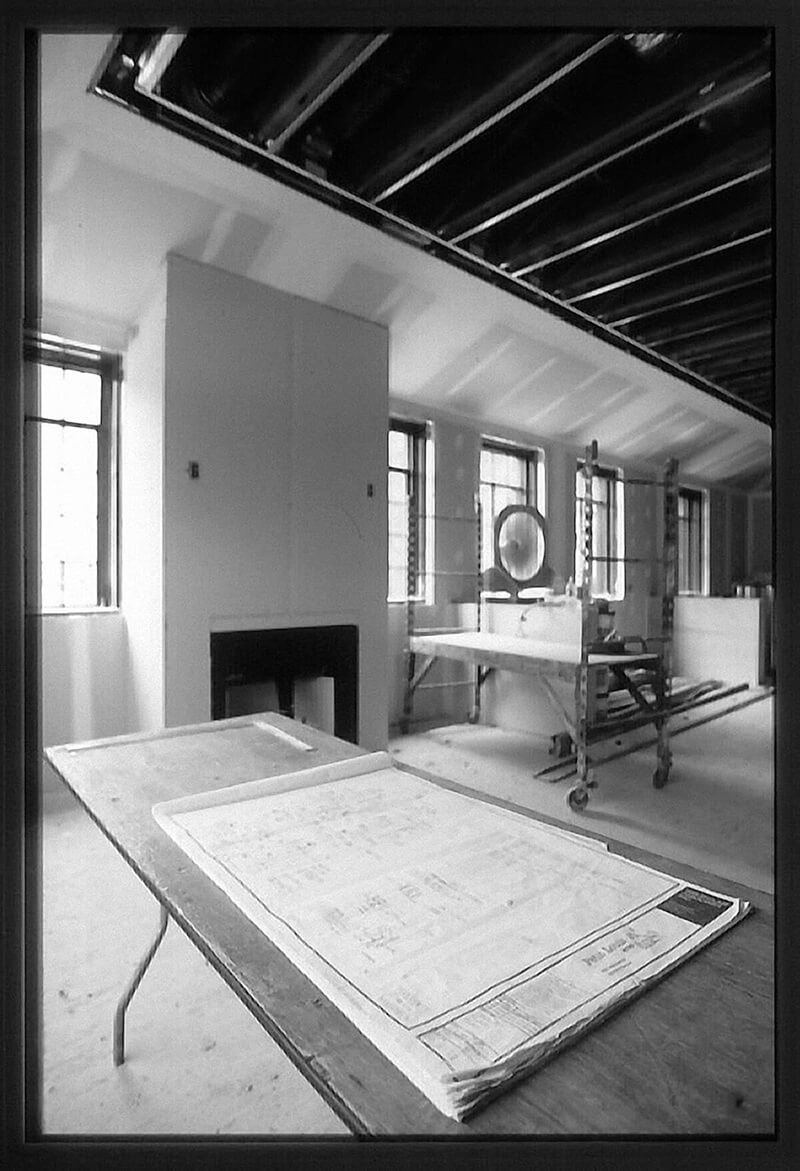

By the time they got back to Baltimore, Wolf, then 35, and Foreman, then 34, were eager to seal the deal and make the former groceryturned-pharmacy-turned-cafe their own. And by the fall of 1999, construction began on the French bistro. The goal, says Foreman, was to create “a real center for the neighborhood.” A big part of the appeal for both of them was that Roland Park—America’s first “garden suburb”—with its wide sidewalks, charming old homes, and tight-knit community, was a neighborhood Foreman knew well. He grew up just five blocks away from “Louis,” as he calls it in shorthand, and he now lives with his family one street over from where he grew up.

“Tony told me that when he was growing up, he used to go to the pharmacy lunch counter at Morgan Millard, and he would get milkshakes,” says Wolf, who grew up in Virginia but now also lives within walking distance of the Roland Avenue restaurant. “I loved that this was his home. I’ve lived in many different places, even within the same town. For someone who got to live in the same place their whole life, that was very special. I loved the fact that Tony had all of these amazing memories right here in Roland Park.”

And so, on the first day of summer on June 21, 2000, with a nod to its Parisian namesake, Petit Louis opened its doors—and thus began Baltimore’s romance with authentic French fare. (At that time, Martick’s Restaurant and M. Gettier in Fells Point were the only other French-focused spots in the area.) “On the day we opened, people were lined up out on the sidewalk into the parking lot,” recalls Wolf, who also has a Tabby cat named Louis. “We served hundreds of people that day,” says Foreman. “We were pretty overwhelmed immediately.”

Clockwise from top: The site of Petit Louis circa early 1900s; the gutted space during construction way back when; Rita St. Clair and Foreman working on design plans in 1999.

or any restaurant in the fickle, fly-by-night culinary world, two decades is something to celebrate (especially as thousands of spots shutter permanently as a result of the pandemic). And, yet, it’s hard to believe that Louis, which has brought such a sense of joie de vivre to Baltimoreans, has only been open for 20 years. In many ways, that’s because of the absolute authenticity you feel from the minute you push open the stained-glass panel front doors and, at least in pre-COVID times, get an oh-so-French double kiss by Lyon-born Patrick Del Valle, who has worked at Louis since 2002. With its blue, white, and red awnings, sublime cheese trolley, chalked-up plat du jour menu, carefully curated French wine list, and zinc-topped bar, Petit Louis is Foreman and Wolf’s own love letter to France, a country they both visit as often as they can.

The wine flows.

At the outset, to alleviate the public perception that French food was fancy or overwrought with its cream sauces and exotic fare (think: frog legs, foie gras, and escargots), the tone was set with an inspired slogan that remains part of the restaurant’s branding today: “It’s fun! It’s French!” From the beginning, says Wolf, “Tony was determined to make it clear that it was going to be fun, not scary. We were both afraid of what the public perception was going to be.”

To add to the idea that French food did not have to be formal or fussy, Foreman and Wolf purposely avoided incorporating décor details such as candles and white tablecloths, though Wolf admits she wanted both. “I was totally freaked out we didn’t put tablecloths on the table,” she says. “Every bistro in Paris has tablecloths, and I like tablecloths. Tony was like, ‘No, that’s going to be too fancy.’ And I was like, ‘I love candles,’ and he insisted, ‘There aren’t going to be candles,’ but he was completely right.”

Also helping to brand the bistro as a place that didn’t take itself too seriously was an illustration of a fictional Louis—a rotund chef bearing a whole fish on a dish. “We went back and forth with the designer in Atlanta. I’d say, ‘I want him fat, now he’s too fat! I want him to look happy, and the fish on the plate has to have a smile and a twinkle in his eye,’” says Foreman of the still iconic Louis logo.

Great consideration was also given to the restaurant’s interior, designed by the legendary Rita St. Clair, who gutted the space and added dramatic touches such as an ornate ceiling inspired by the famed pastry shop Ladurée on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, standing table lamps made in Italy with etched glass globes, marble-topped tables, and faux-painted walls that imparted the patina of age. “Tony told the faux painters that he wanted it to look like someone had been smoking Gitanes cigarettes here for over 100 years,” recalls Wolf. “I think that’s part of the magic—when you walk in, you have no idea that it’s a new restaurant. We wanted you to feel like you were in a 100-year-old bistro.”

The plat du jour.

“The fantasy was that this is what it would be like if the English developer who built this center in 1897 had found a French chef and opened a cute little restaurant in the neighborhood and it had always been here,” says Foreman. “And it was seasonal and felt French but very of the neighborhood and was in no way intimidating, but authentic at the same time. . . that’s what we were trying to strike—the imagined history is what informed the interior.”

While the backstory was imagined, it was vividly brought to life. “I came in here and I was like, ‘Wow,’” says sommelier Marc Dettori, who has been with Louis since the early days and is a native of Villefranche-sur-Saône near Lyon, France. “In my heart, it was like being in France,” says Dettori, whose small stature, twinkly eyes, and heavy accent often lead patrons to mistake him for the fictional Louis. “It’s exactly the quality of food service, décor, and presentation that you’d find in France.”

“It feels like I’m home,” seconds Del Valle, who still fondly recalls his first meal at Louis. “I ordered the onion soup,” he says. “It was really, really good. We do all our stock in house, so the flavor is very intense. I also had the duck confit, which was excellent. The food isn’t fancy here, it’s just classic dishes you’d find anywhere in France, and well-executed. Nothing is Americanized. It’s very close to the real thing.”

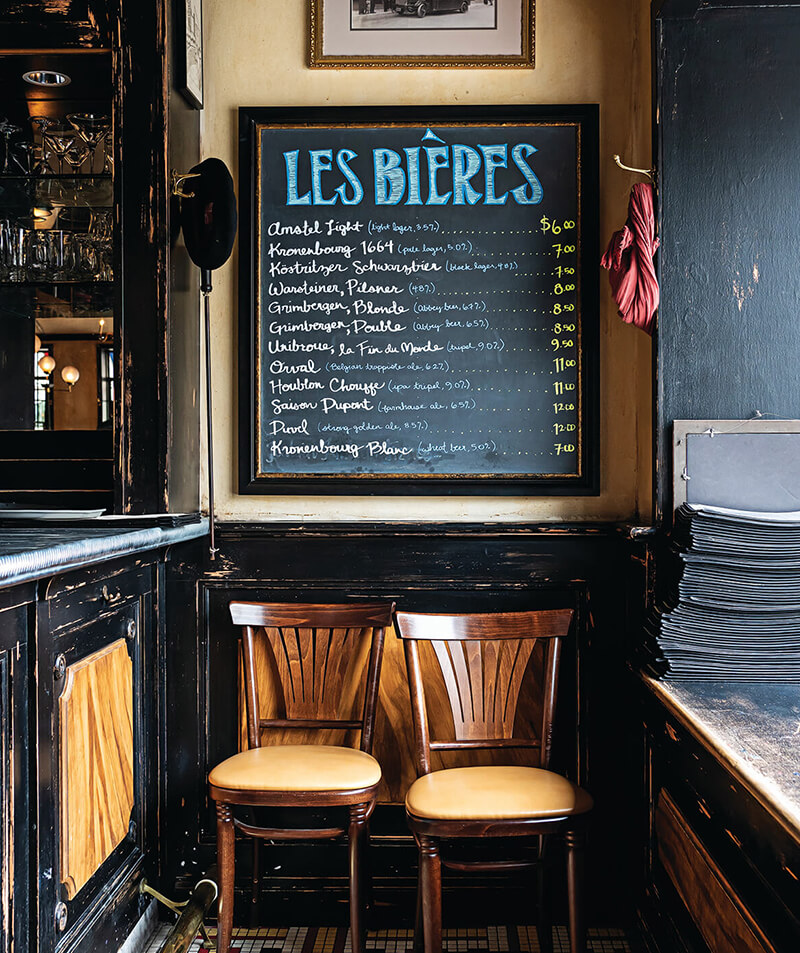

Clockwise from top: The dining room invokes a truly classic French bistro; Sommelier Marc Dettori suggests the perfect pairing; the chalkboard list of beers; Patrick Del Valle ready to greet guests; the onion soup.

For the most part, the restaurant’s recipes—refined yet homey, and impeccably sourced—have stayed the same seasonally, though chef Scanga puts his own spin on some of the dishes. “The pâté maison, the eggplant Napoléon, the frisée au lardon, the onion soup, were all on the menu from the beginning,” says Foreman. “The menu pretty much wrote itself.”

For the first few years, so as not to intimidate the customers, there was no French on the menu, and dishes like magret de canard (breast of duck) appeared in English only. “We didn’t want people to be like, ‘I don’t understand,’” recalls Wolf.

Dettori prepares for service.

Still, there were times when the guests didn’t understand how best to consume the cuisine. “I remember back when I was a server, we were doing a bouillabaisse and one of the guests asked me for ketchup,” says Del Valle, smiling at the memory. “I went back in the kitchen and said, ‘Tony, one of the guests asked for ketchup for the bouillabaisse—I cannot do that! I don’t want to do that.’ And Tony was like, ‘Hey, if they want ketchup, give them ketchup.’ It was heartbreaking.” (“The guest bought the bouillabaisse,” cracks Foreman, when asked about the incident. “It was his now.”)

But as Louis has aged, the patrons have grown wiser and worldlier, too. They come for quiche Lorraine, beef bourguignonne, or a simple plate of house-cured salmon with crème fraîche. They drink bottles of Champagne at noon. They order snails that, in the early days, were flung across the dining room as customers tried to wrestle them from their shells.

“One of the things that’s so extraordinary is that these things were not here before we started doing them,” says Wolf. “And seeing children eating escargots is so special. Twenty years later, they grow up and go, ‘Oh, my god, we have to go to Louis.’ It’s such a compliment that guests trust us, and they go to France and come back and they’re like, ‘I feel like I’m in Paris again.’”

Former Petit Louis executive chef Ben Lefenfeld, now the chef-co-owner of La Cuchara, remembers his five years at Louis fondly. “Petit Louis is a very special place,” he says. “Some restaurants create an intangible experience of food, service, and atmosphere that transports you to another place or time. This cannot be replicated or reproduced—Louis is one of those places.”

The eggplant Napoléon appetizer.

On that late winter afternoon, Lainy Lebow-Sachs, Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s former adviser, wanders in with Myrna Cardin, Senator Ben Cardin’s wife. “This is like my kitchen,” she says to Del Valle. “I had dinner here last night and lunch here today. Why cook when you can go to Petit Louis?”

Even in the age of COVID, that seems to be the sentiment. To wit, regular customer Bain and his wife, Millicent, have dined at Louis since the very beginning, and during the COVID crisis have remained undeterred, making the walk to the restaurant three times or so a week. So deep is their affection that when the Roland Park couple recently decided to downsize, having close proximity to Louis was one of the stipulations for finding a new house. “It had to be within walking distance, that was one of the criterions,” says Bain. “We marked it out. When we move, the walk will be seventenths of a mile.”

Whether patrons drive over from other neighborhoods or walk from their homes in Roland Park, everyone is there to celebrate what’s right with the world. “Life happens here,” sums up Wolf. “From people coming here after they’ve gotten married, or a couple going out for the first time since their child was born, or people trying something they’ve never eaten before, Petit Louis affects their lives. Now they know about good food and wine. Food is life, and we need it to live.”

In other words, a little foie gras terrine, plus a warm baguette, and a glass of Sauternes—all on offer at Louis, of course—can go a long way, all the more so in these uncertain times.