Food & Drink

The Great Restaurant Reinvention

How baltimore restaurants are pivoting in the pandemic.

Photography by Scott Suchman. Illustrations by Gwen Keraval.

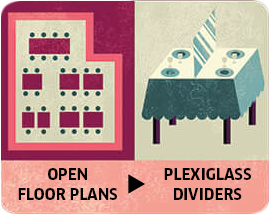

On March 16, the day Governor Larry Hogan closed all restaurants and bars for in-person dining in Maryland due to the COVID-19 crisis, Irene Salmon, co-owner of Dylan’s Oyster Cellar, was in something of a state of shock. The beloved oyster bar at the corner of 36th Street and Chestnut Avenue in Hampden had been having a great run ever since opening its doors in December 2016. Most days of the week, the neighborhood restaurant was bustling with seafood lovers craving old-school dishes—coddies, cured anchovies, soft-shell crab sandwiches—washed down by local beers on tap. And the dining room, packed with everyone from hipsters perched on bar stools to families crammed into wooden booths, was convivial and carefree. Fast forward to early July when an alarm sounded every 30 minutes to signal that it was time for staff to sanitize hightouch surfaces with industrial-grade disinfectants and cleaners. Long gone were the half-pencils and paper oyster menus that once graced every table. Masks were now mandatory for servers, as well as guests, who also got their temperatures taken. Interior capacity was capped at the mandated 50 percent, though in the small space, with tables spaced six feet apart, that allowed room for only 20 patrons. Weather permitting, sidewalk dining was available.

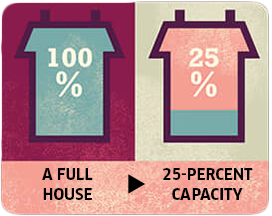

A few weeks later brought more doom and gloom, as Baltimore Mayor Jack Young once again shut down restaurants for indoor dining for two weeks. And by early August, it was back open at quarter capacity, though by that point, says Salmon, “no one wanted to sit inside, even when the patio was full.”

Even on a good day pre-COVID, with profit margins at four to six percent, it wouldn’t take much to sink a restaurant, especially a small independent one like Dylan’s. And now there’s even less room for error as the small business is reeling from lost revenue, while fixed costs such as rent and utility bills, and even items like laundry service for linens, remain the same.

“[Mid-March] was really wild,” says Salmon. “We had to totally overhaul our business model and lay off half of our staff. We went from being a thriving business to a failing one overnight— and every restaurant I talk to is in the same position.”

For Irene and her co-owner and husband, Dylan, overhauling their business model has meant everything from offering carryout to going cashless, limiting tables to four and under, and creating a reservations-only model. Of course, what works one month might not work in another—and just as they’ve settled into one routine, they’ve had to contemplate their next move. By late August, Salmon and her team were busy thinking about what would happen come winter with an eye toward a grab-and-go business. “It’s like we’ve fallen into a black hole,” says Salmon. “We need to see what the new norm is.”

And while they’re holding on for now, the losses—after years of work and a lifetime of financial and creative capital— have been devastating. “We are still at a 40 percent loss,” says Salmon, who was able to bring back some of her staff thanks to a federal paycheck protection program (PPP) loan. “And that’s not because we’re not successful in terms of putting out good food or giving good service—it’s all the things that are happening around us that are stifling what we were able to do before, when there weren’t these limitations.”

Despite the grim forecast for the hospitality industry, with a predicted nationwide loss of $240 billion in sales by year’s end, according to the National Restaurant Association, Salmon is staying hopeful. “It’s fine if we eat our savings to survive, but at a certain point you have to ask, ‘When is the right time to fold?’ In this situation, it’s not right now, but I am watching the trends very closely.”

rior to the coronavirus pandemic, there were some 11,000 Maryland restaurants, from large chains to small independent eateries, employing a little over 200,000 people. Since mid-March, many have shared similar struggles to Dylan’s—and thousands have already folded. “We are projecting that 35 percent of all restaurants in the state of Maryland are going to close permanently,” says Marshall Weston, president of the Maryland Restaurant Association. “And that’s an estimate,” he stresses. “The longer this continues, and restaurants have a restricted seating capacity, and consumers are still uncomfortable eating out as regularly as they used to, these closures are going to happen.”

rior to the coronavirus pandemic, there were some 11,000 Maryland restaurants, from large chains to small independent eateries, employing a little over 200,000 people. Since mid-March, many have shared similar struggles to Dylan’s—and thousands have already folded. “We are projecting that 35 percent of all restaurants in the state of Maryland are going to close permanently,” says Marshall Weston, president of the Maryland Restaurant Association. “And that’s an estimate,” he stresses. “The longer this continues, and restaurants have a restricted seating capacity, and consumers are still uncomfortable eating out as regularly as they used to, these closures are going to happen.”

Maryland’s restaurant scene was going strong and the city was very much in the midst of its foodie renaissance prior to COVID. “The weather this winter and spring was relatively mild” says Weston. “In January and February, people were out and about, and restaurant sales were doing well—everyone felt they were off to a good start for the new year.”

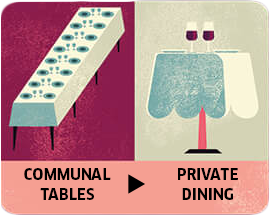

Seven months into the pandemic, the idea of a crowded dining room or a three-deep bar seems like a different reality. “Now it’s just the reinvention of restaurants,” says Weston. “After COVID hit, what we’ve all learned is that we’ve taken restaurants for granted. We were all used to dining out for several meals a week and those things helped create a thriving restaurant environment. Now that those things are taken away from us, restaurants are struggling, and people are struggling with their new routine of not being able to go out and dine with friends and family or go to bars and venues like they once used to. All of these things have traumatized the industry.”

Reopening and recovery for hospitality workers and consumers alike will no doubt take time, but the culinary scene is nothing if not innovative. While there are many unknowns, one thing is for certain: In the age of COVID, and likely post-pandemic, restaurants will need to be reimagined, as they not only devise new ways to stay solvent but also restore confidence to consumers that restaurants are, indeed, safe spaces.

“Overall, restaurants are a very resilient group of businesses,” says Weston. “They have the ability to adapt. The only thing that is certain now is that there will be changes in the way consumers go out to eat.” Ashish Alfred, owner of Duck Duck Goose in Fells Point, puts it like this: “Whatever gets thrown our way, we will find a way to adapt.”

“OVERALL, RESTAURANTS ARE A VERY RESILIENT GROUP OF BUSINESSES. THEY HAVE THE ABILITY TO ADAPT. THE ONLY THING THAT IS CERTAIN NOW IS THAT THERE WILL BE CHANGES IN THE WAY CONSUMERS GO OUT TO EAT.”

ecessity, as they say, is the mother of invention and nowhere is the fighting spirit stronger than scrappy Baltimore, a city that has weathered these tough times with grit and grace.

ecessity, as they say, is the mother of invention and nowhere is the fighting spirit stronger than scrappy Baltimore, a city that has weathered these tough times with grit and grace.

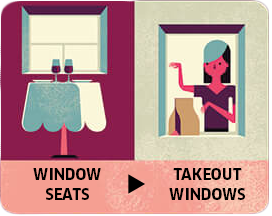

Locally, that means virtually all places have pivoted to carryout, with some, like The Corner Pantry in Mt. Washington and Miss Shirley’s Cafe in Roland Park, even implementing new take-out windows, but other ideas have evolved, too. The Basque-themed La Cuchara in Hampden-Woodberry created a virtual marketplace with pantry staples for sale, from flour to sugar to olive oil, and durable carryout dishes like honey-roasted chicken and pickled beets, while paring down their menu for in-person dining.

Just down the street, James Beard-winning Woodberry Kitchen followed suit with its Here for Us market, a conglomeration of pantry staples from Woodberry’s own kitchen, plus provisions from area restaurants, growers, and cheesemakers, from Karma Farm to Hawk’s Hill Creamery. Taco kits have been all the rage at Grand Cru and Clavel, which is also selling T-shirts. Cook-at-home pizza kits were for sale at Homeslyce’s various downtown locations. Places like Orto in Station North and Aldo’s Ristorante in Little Italy have revamped their lineup for well-priced, family-style meals that riff off the regular menu.

And suddenly, fine-dining temples such as Foreman Wolf’s Charleston and Cinghiale are doing first-time curbside carryout and patio dining on the sidewalks of Harbor East. (The restaurant group even had arts and crafts for sale at a newly created pop-up farmer’s market outside their Roland Park property Johnny’s.)

Restaurant owners have also made themselves more visible than ever to continue to build trust with patrons. Early in the crisis, Linwood and Ellen Dame of Linwood’s waved from sidewalks as patrons drove by the pick-up line, while Tark’s Grill co-owner Bruce Bodie did his own deliveries to customers’ houses. Beloved chefs, such as Chris Amendola at Hampden’s Foraged, offered “cook-alongs,” selling market baskets of ingredients for DIY gourmet meals, and rolled out cooking demonstrations and classes online. And all across the city, there were tents (Rye Street Tavern installed chandeliers and air-conditioning in theirs), colorful umbrellas, and festive flowers to make al fresco dining more attractive, especially during the sweltering summer months. All over the country—and the world—restaurants have responded with out-of-the-box solutions, such as The Inn at Little Washington in Virginia, where mannequins —dressed in 1940s costumes—sit at empty tables to help fill up the dining room, or Mediamatic ETEN in the Netherlands, which hosts diners in individual glass greenhouses.

But even with all of these tactics, most spots are on life support. “Right now, restaurants are doing everything they can to survive and to prevent from closing permanently,” says Weston. “No restaurant segment has been spared, from fine-dining spots to small diners—all restaurants are in survival mode.”

s rules and regulations change almost daily, “pivot” has become the word of the year. And restaurants have struggled to adapt on an almost minute- by-minute basis. In addition to the virtual marketplace at La Cuchara, for instance, the restaurant has created themed meal kits such as Parisian picnics and DIY cupcakes, and collaborated with the Charm City Night Market, supplying ingredients for participants in a virtual cooking event. When the restaurant earned a nod for its wine list from Wine Spectator, they featured a cellar raid with cut-rate prices. “We’ve been pretty scrappy,” says chef/co-owner Ben Lefenfeld. “We try to figure out something to get by on a weekly basis. And we will keep doing that.”

s rules and regulations change almost daily, “pivot” has become the word of the year. And restaurants have struggled to adapt on an almost minute- by-minute basis. In addition to the virtual marketplace at La Cuchara, for instance, the restaurant has created themed meal kits such as Parisian picnics and DIY cupcakes, and collaborated with the Charm City Night Market, supplying ingredients for participants in a virtual cooking event. When the restaurant earned a nod for its wine list from Wine Spectator, they featured a cellar raid with cut-rate prices. “We’ve been pretty scrappy,” says chef/co-owner Ben Lefenfeld. “We try to figure out something to get by on a weekly basis. And we will keep doing that.”

The big question is, will restaurants survive? “They are going to be changed,” predicts Tony Foreman of Foreman Wolf restaurant group. “Things will continue to tilt in favor of chains and larger-scale places. Smaller, hand-crafted, curated, and cultivated experiences will be fewer and fewer, and the attraction to creating those things is going to be less and less—there’s just too much risk.”

But restaurants—derived from the French word “to restore”— with their hundreds of years of history, are not going away. Even now, with safety measures in place—temperature checks, mandatory health waivers, masks—much of the public’s enthusiasm for eating out, or carrying in, has not been deterred.

“People have to go to restaurants,” says Will Mester, co-owner of Le Comptoir du Vin in Station North. “People have to go out, they have to socialize. Restaurants provide that space—this is what cities are all about.”

In a post-pandemic world—that is, if we can even begin to imagine it—there’s hope that things will not only be okay, but even better than before. “Out of the Great Depression came The New Deal and a lot of innovation,” says Lefenfeld. “This is something that my wife, Amy, has brought up several times. Out of the coronavirus, you’re going to see a little bit of a renaissance. You’re going to see people thinking about different ways to approach the business of owning a restaurant and it’s going to change the overall landscape for the better.”

On the following pages, we check in with six local eateries whose innovations have helped keep them afloat during these challenging times and whose approach to running their businesses are forever changed.

clavel

TAQUERIA AND MEZCALERIA / REMINGTON

⬥ Their Plan B: Created a to-go menu featuring burritos, taco kits, and signature cocktails; raised prices by 20 percent; added lunch hours and a lunch truck for safe ordering.

Above: The takeout truck. Below: Two diners enjoying the outdoor patio; handstamped carryout bags; wrapping a burrito; preparing tacos for takeout.

On Saturday, March 14, as the coronavirus was beginning to spread across the country, Clavel co-owner-chef Carlos Raba was settling down to dinner with some friends at his always-packed restaurant. “I saw 200 people coming in and out and felt an anxiety like I’ve never felt, I was alarmed,” recalls Raba. “I could feel it from our staff and our customers.” Sunday brunch was no better. After he consulted with co-owners Lane Harlan and her husband, Matthew Pierce, they decided to close the next day for indoor dining. Twenty-four hours later, while Governor Larry Hogan was shutting restaurants for in-person dining across the state, the trio was already devising an entirely new business plan for their James Beard-nominated taqueria.

“Restaurants are community gathering places vital to our culture in Baltimore. Dining is integral to our reality as humans.”

—Dave Seel, founder, Blue Fork Marketing; The Baltimore Restaurant Relief Fund

Driven by a sense of duty to both their staff and patrons, they wasted no time in coming up with a novel carryout approach called Pisa y Corre, inspired by the convenience stores of Raba’s hometown in Culiacán, Mexico. “I used to go to a drivethrough market called Pisa y Corre, which translates to ‘stop and run,’” Raba says. “You could go buy beer and groceries there.”

Within a day of their restaurant rehaul, Raba and Harlan, who handles front-of-house, were back in the kitchen together. “It was just like when we first opened, just me and Carlos on the line,” says Harlan. “There is no one to save you when you are drowning—you just have to push through and make it happen.” As Harlan ran outside with bags of burritos, taco kits, and containers of cocktails, faithful fans lined up in cars along Huntington Street. “That first Friday was more business than we ever did,” she says. “There was a flow of large tickets coming in, and that was with less than 10 people working.”

Of course, invention is nothing new for the Harlan and Raba, who’ve been culinary leaders in Baltimore for half a decade, opening Maryland’s first mezcaleria in 2015 and putting the restaurant’s Remington neighborhood on the map nationally.

During the pandemic, Clavel has continued to evolve, adding a food truck (an old UPS vehicle) for diners who want to enjoy their new 24-seat patio built for distancing. (The interior dining room remains closed.) Also, with staff in mind, and to recoup lost revenue, Raba and Harlan increased pricing by 20 percent, created a tip pool, and implemented a common hourly wage among the frontand back-of-house staff, a practice they hope will help highlight the inequities in restaurant kitchens, where employees typically make lower wages. “We have an opportunity to reimagine how we were doing things,” says Harlan. And while it’s still hard to cover costs, she and Raba remain resolute that the beloved taqueria’s string lights will twinkle for years to come. “We are going to make it,” says Raba. “We’re doing everything within our power to be a place that our employees and community can count on. That gives us the fire to continue fighting.”

le comptoir du vin

BISTRO & BOTTLE SHOP / STATION NORTH

⬥ Their Plan B: Launched a bottle shop; pivoted to carry-out; transformed their dining room into a hip general store.

Above: Bottles of natural wine for sale. Below: Will Mester at work in the restaurant’s kitchen; Le Comptoir du Vin co-owners Will Mester and Rosemary Liss.

In early August, Rosemary Liss and Will Mester were in the midst of a transformation. The owners of Le Comptoir du Vin had taken a week off to build new shelves in their charming Station North bistro, pick up new products in New York’s Hudson River Valley, and test new recipes for their latest shift in the ever-evolving shuffle of restaurant ownership amidst COVID-19.

“I can’t imagine that people in Paris are wondering what’s the fate of their restaurant culture. It’s so tied into everyday life. It’s the fabric of those cities and they are just as important here. Restaurants will survive.”

—Will Mester, chef, Le Comptoir du Vin

“We have been constantly reevaluating what it means to be a restaurant right now,” says Liss, “and thinking about how we can make it sustainable for the long haul.” In the early spring, within a week of closing their popular restaurant, the couple reopened as a bottle shop, utilizing their natural wine niche and updating their website for online orders, before eventually adding carryout from a downsized menu. Prior to the pandemic, “We had been running full speed, it was a lot to keep up with, then suddenly it all stopped,” says Liss. “This has forced us to slow down. We’ve been using this time to reassess the kind of atmosphere we want when we are able to reopen.” Even as the city eventually added indoor dining restrictions, a reduced-capacity dinner service just wasn’t financially viable with only 34 seats, and by the end of summer, they decided to simplify further, reopening on August 12 as a hybrid general store. “Many restaurants were forced into doing these little markets because of COVID,” says Liss. “For us, it became such an inspiration that we wanted to take a step further and make a permanent part of our business instead of just a thing we had to do to get by.”

Modeled after European market-cafes, the old chalkboard now touts seasonal grab-and-go dishes, including elegant takes on salads and sandwiches fit for socially distanced picnics and hikes. And where rustic tables once sat, the walls are stocked with a colorful assortment of hard-to-find pantry items, from pastas and preserves to olive oils and tin fish, which they hope to keep after guests return. “I’m still surrounded by beautiful food,” says Mester. “As a cook, I’m first interested in finding the best possible ingredients. I’m excited by the possibility of people taking these products home, then coming back and telling us what they did with them.”—Lydia Woolever

good neighbor

CAFE WITH HOUSEWARES / HAMPDEN

⬥ Their Plan B: Created a hybrid retail-restaurant complex; outdoor deck; socially distanced happy hours.

Above: The housewares for sale. Below: Artisanal toasts; Chef Durian Neal and co-owner Shawn Chopra; hand sanitzer.

Since Shawn Chopra was a kid in Canada, he dreamed of becoming an architect. He read books on design and was inspired by world travels, most notably to his mother’s Chandigarh, India. In 2015, the former physical therapist finally developed the idea for his own hybrid retailcoffee shop to serve as a respite from the age of Amazon. “I wanted to create something that felt like going to your neighbor’s house, where you can sit and enjoy their space,” says Chopra, who co-owns Good Neighbor in Hampden with his wife, Anne. After saving up, “We worked up the courage about a year ago, leased the space, and started working on it every day.” But the timing suddenly seemed less than ideal as, a week before opening, the first coronavirus cases arrived in Maryland. “We were waiting on our final inspections when everything happened,” he says. “We were like, ‘Are we even going to open?’”

“It’s such a challenging time for restaurant owners and businesses with no clear light at the end of the tunnel. That’s the hard part—being stuck in purgatory.”

—Chris Amendola, owner, Foraged

The small team, including chef Durian Neal, formerly of Ida B’s Table and Momofuku, spent the next two months planning a carryout menu, building an outdoor deck, and adding Greenhouse, a sister plant shop out back. “I’m just happy I can see the vision I’ve been thinking about in my head for so many years,”says Chopra. That vision was to create a lived-in homewares store, where, in addition to open shelves boasting local and imported linens, ceramics, and art books, the chair you’re sitting on and the coffee cup in your hand are all for sale, too. The concept has been impacted by limited indoor dining, but the occasional hand-woven rug purchase has helped pay the bills. The elevated deck with lush landscaping has also been a major draw, as customers flock for fresh air and safe social distancing.

At Good Neighbor, even the menu, focused on salads and toasts, is aesthetically pleasing; this is not your average avocados lathered slice of bread, instead including items like brioche with house-made peach-chamomile jam, tahini butter, and edible flowers. “I’m a firm believer that people eat with their eyes first,” says Neal, who recently added street food-inspired weekend happy hours and is dreaming up a dinner series with their recently approved liquor license. “Every day is just fingers crossed, but we have a great team, and we’re growing slowly,” says Chopra. “Our goal is to use this time to build a strong business that can sustain itself once COVID is over.”

Judging from the lines along Falls Road, he already has.—Lydia Woolever

woodberry kitchen

FARM-TO-FORK RESTAURANT / WOODBERRY

⬥ Their Plan B: Launched a CSA, plus a vast virtual marketplace; ongoing patio dining with innovative safety protocols.

Above: Woodberry bartenders Hannah Baker and Galo Ayora at your service. Below, clockwise:Tomato salad; the patio during dinner service; a flag signals servers; produce for sale.

“You have restaurants that are really telling stories. You need people to be able to speak about who they are and bring their culture to the forefront—there’s no better way to do that than through food.”

—Dave Thomas, restaurateur

As servers visited tables to share the stories of seasonal dishes that showcased the winter’s work of local growers, March 15 was just another service at Woodberry Kitchen. But the next day, as restaurants were ordered closed across the state, it was more akin to a snow day, says James Beard Award-winning chef-co-owner Spike Gjerde. “There’ve been times when we’ve had to deal with weather events that come and go quickly,” he says. “And this just felt like that, like something we had to prepare for. But the enormity of it, as to how severe it was going to be, had not sunk in.” Nearly seven months later, with patio dining in full swing, it might feel like business as usual were it not for the self-busing station at the end of each table, a flag system to summon servers for reduced table contact, and hand-sanitation stations that dot the patio. But inside the homey dining room is a different story. The letterboard menu still lists specials from March 15—from braised rabbit leg to cast-iron chicken—the last night of regular dinner service. On March 27, wood tables were replaced by industrial refrigerators, ice chests, and cardboard boxes, as the restaurant transformed itself into an ad-hoc gourmet grocer with their Here for Us market, featuring some 160 items. “I wanted to bring in as many producers, makers, or whomever we could wrangle if it would be helpful for them to have their products on the market,” explains Gjerde. “The conception was our own PPP—produce, pantry, and prepared foods.”

Ultimately, the concept was not profitable, though the restaurant is still sticking with its curated CSA box of local produce, plus pantry items. “That’s been really successful,” he says.

At press time, the restaurant had yet to reopen for indoor dining, but Gjerde continues to look for new ways to support local growers and producers and connect them to the community. “We adhere to this ethos around sourcing and trying to do something more thoughtful with the way we eat,” he says. “That’s not going to change, though how we get there might have to. In this moment, I’m compelled to think about finding a way to do it that doesn’t feel as vulnerable.”

Then & Now

RESTAURANT’S PAST AND PRESENT: THE STORY IN PICTURES

well crafted kitchen

MOBILE PIZZA KITCHEN / EVERYWHERE

⬥ Their Plan B: Taking their catering pizza truck on the road to area neighborhoods.

Above: Well Crafted owners Laura and Tom Wagner and Ryan and Liz Bower with their boys Emerson and Brooks. Below, counter-clockwise:: The jalapeno popper pizza; A pizza comes out of the oven; a happy customer.

“Restaurants need to follow all guidelines and prioritize the safety of their guests and employees over profit. If landlords are supportive and partnered with restaurant owners, I believe it is possible.”

—Zack Mills, chef, True Chesapeake Oyster Co.

Like many restaurant owners in the midst of the pandemic, the owners of Well Crafted Kitchen, the farmto- table pizza space at Union Collective, transitioned to takeout to survive. “We decided our goal would be to sell 250 pizzas each week with takeout,” says Liz Bower, who owns the business along with her husband, Ryan, and friends Laura and Tom Wagner. “And that didn’t touch rent or overhead—it was just to pay for our team and products from our farmers. In the first few weeks, if we didn’t make that goal, we were unsure if we could stay open, but we reached that goal each week.” Early June, however, was a different story, as business slowed to a crawl. The partners knew they needed a new solution to stay afloat. And the answer was in their backyard, or in this case, the parking lot at Union Collective, where their catering truck, a 1949 Dodge retrofitted with a wood-fire pizza oven, usually used for events, had stood idle for months. “We realized we had to do something with our truck,” says Bower. In fact, she and her partners actually launched their pizza business in 2016 with mobile pop-ups before becoming a brick-and-mortar operation at Union. Going back to their roots, the foursome put out a call to the community asking if anyone would be interested in having them make “truck stops.” Responses, including one from the Abell neighborhood in Charles Village, came flooding in. “That community has been super supportive of us,” says Bower. “In the early days, they supported us when we sat at the Waverly Farmer’s Market. Before we even said we were going, they had sold 100 pizzas.” Months since that first pop-up, the truck stops— Wednesdays and Thursday (plus carryout at Union on Thursdays through Sundays)—have kept the business rolling along. “In the past, we’d have two events open to the general public in a year,” says Bower. “Now two-thirds of our business is what we do with the truck.” In addition to Abell, the mobile pizza kitchen has parked in Cedarcroft, Lutherville, and Bower’s own Rodger’s Forge. “One of the things we’ve loved about the truck stops is seeing that people are excited to be a community,” she says. “It’s a bright light—one of the little positives we can celebrate.”

tark's grill

NEW AMERICAN FARE / LUTHERVILLE/TIMONIUM

⬥ Their Plan B: Created a carryout menu with discounted and flat-rate pricing; newfound focus on outdoor dining.

Above: The patio. Below: Preparing takeout orders; to-go goods; cocktails to go; sanitizing the plexiglass between booths.

On May 28, the date the state announced the reopening of restaurants for outdoor dining, it didn’t take long for customers to come bounding back to Tark’s Grill in Greenspring Station. “It was instant,” recalls Gino Cardinale, who co-owns the popular Lutherville-Timonium cafe with his husband, Bruce Bodie, and executive chef-partner James Jennings. “Governor Hogan was still talking on the television when our phone started ringing for reservations.”

“If you want to see restaurants survive, embrace your favorite places—and through all of this, be sure to go there a few times.”

—Martha Lucius, local restaurant strategist

In fact, since that late spring day, the reservations, including those from regulars, such as PR maven Edie Brown, former Maryland State Department of Education superintendent Nancy Grasmick, and former Maryland Public Television host Rhea Feikin, as well as new customers, have kept coming. Of course, it hasn’t hurt that the courtyard patio, with its enchanting pergola, a burbling fountain complete with fire feature, an outdoor bar, and garden-like atmosphere, feels like an oasis in these troubling times.

The other big draw is that while many restaurants are doing carryout, Tark’s to-go menu has been offering discounted prices. “We didn’t just take in-house prices and say we are going to shove it in a box,” says Cardinale. “We put together what we call ‘crisis-friendly prices,’ setting all dinner entrees at $25 flat, whether you were getting the New York strip or the double crab cakes. And while we were sacrificing some profit margin, people are placing larger orders with their college kids at home. Our plan worked.”

Prior to COVID, thanks to a spiffy new interior, the restaurant had been enjoying its best first quarter in its history, says Cardinale. But even during the crisis, while other restaurants have seen waning sales and worse—much like the couple’s much-loved City Café in Mt. Vernon, which closed as a result of the pandemic— from summer through fall, Tark’s has been bustling with most of its 100-seat patio filled many nights of the week and up to 100 carryout orders nightly at the height of the shutdown. “Our revenues in June were the same as last year,” says Cardinale. “July has been a little busier because people didn’t go away this summer and August is up.” (And that was despite the fact that, like many area restaurants, they closed as a precaution for several days when an employee tested positive for the virus.)

The reason people have returned to dining out is simple, says Bodie. “People still require a restaurant in their life, even in a global pandemic,” he says. “The act of seeing friends and sharing a drink or a meal together is why people like to come out. We are just not designed to be quarantined all day.” And Cardinale really appreciates that his customers trust him to serve up good food and company—and keep them safe. “We tell people that even though you can’t see it,” he says, “we are smiling under our masks.”

Q&A

A NATIONAL EXPERT WEIGHS IN ON THE ENORMITY OF THE CURRENT CRISIS AND ITS AFFECT ON THE INDUSTRY. “RESTAURANTS ARE NOT DESIGNED WITH AN ON-OFF SWITCH,” HE NOTES.

Of all the business sectors impacted by the COVID crisis, the food-service industry has been among the hardest hit. Between March and June, the National Restaurant Association forecasts a loss of $145 billion in revenue, with more than eight million restaurant employees laid off or furloughed at the height of the shutdown. We spoke with the association’s executive vice president for public affairs, Sean Kennedy, about what the culinary landscape looks like now and his predictions for the future.

How were restaurants doing before COVID? As we moved into the first quarter of 2020, the signs were encouraging. Spending was up. We thought this would be one of our better years.

What happened when COVID hit? On Saturday, March 14, Hoboken, New Jersey, was the first city to shut down dining operations effective at midnight. Suddenly, you had an industry that was preparing for St. Patrick’s Day and Mother’s Day that found itself shut down on a nationwide basis.

“WE CAN’T LIVE WITHOUT RESTAURANTS”

—Cindy Wolf, executive chef, Charleston

How many restaurants are projected to shut down permanently? You have to make assumptions about how long the pandemic will last and what the reopening timeline will be. Restaurants are not designed with an on-off switch. Restaurants are designed to be in use seven days a week, roughly 14 to 16 hours a day. It’s a very thin profit margin of four to six percent and that assumes a full house, particularly a full house in the high season, which is what we’ve been in since mid-March. The timing of this was particularly challenging.

How have restaurants pivoted? What has been remarkable is how quickly so many small businesses redefined themselves over a 10-day period. Restaurants that swore they would never do takeout and delivery went back to basics and said, “How do we make something that is going to be delicious and so distinctly identifiable to this restaurant but can travel through a third-party delivery or be picked up at a counter?” Another thing is cocktails to-go. Margins on cocktails to-go are such that, for some restaurants, that’s almost 20 percent of their monthly revenue. Also, a lot of restaurants are making fewer dishes with fewer total ingredients. This helps lower costs and increase efficiencies in the back of the house.

What are some of the bigger struggles right now? The biggest fear is that restaurants are going to be closed down again. It is so capital-intensive to open up a restaurant— if you get it wrong on how many people will walk through your doors or the state shuts you down again, that’s a lot of inventory. You can’t be wrong too many times.

Will one type of restaurant fare better than another? If you’re not in a takeout and delivery space, you’re not going to exist. Most high-end restaurants might be able to afford to weather the storm a little longer because they are destinations. We are seeing that millennials are more attuned to third-party delivery or takeout. We are waiting to see what the consumers older than millennials are going to do in a post-pandemic world. Will they return to the dine-in experience in the same numbers?

Any trends you’re seeing right now? We’re all looking to see what the rise of the ghost kitchen will be. [A ghost kitchen is a professional cooking facility, in which all food is prepared to-go.] Is there going to be more of an effort to do virtual restaurants that just do takeout?

Even in a pandemic, why do some people dine out? When you talk to people about what they miss the most, it’s always about not being able to go out to eat. It gives them a feeling of comfort, and that everything is going to be okay.

Who will be hardest hit? If you are a small independent restaurant or a small franchise owner, you have less access to capital. You are a lot more vulnerable, and for those restauranteurs and chefs, that’s their proving ground. It can’t be only larger restaurant groups or chains or independents that are sustainable— we need to make sure all segments of the industry can find a way to survive.