GameChangers

From Ship to Shore

Living Classroom Foundation’s James Piper Bond has kept on course for his cause.

Everything you need to know about James Piper Bond, president and CEO of Living Classrooms Foundation (LCF), can be summed up in his office. It’s located in the foundation’s headquarters on the waterfront in Fells Point, located at the Frederick Douglass Isaac Myers Maritime Park, in a building that features the kind of floor-to-ceiling views of Baltimore’s harbor that are the stuff of commercial real-estate dreams.

Yet Bond’s office sits at the back of the building, facing East Baltimore, a more fitting compass direction considering what LCF does. He’s a leader who never takes his eye off the mission of the organization he’s shaped for more than 35 years.

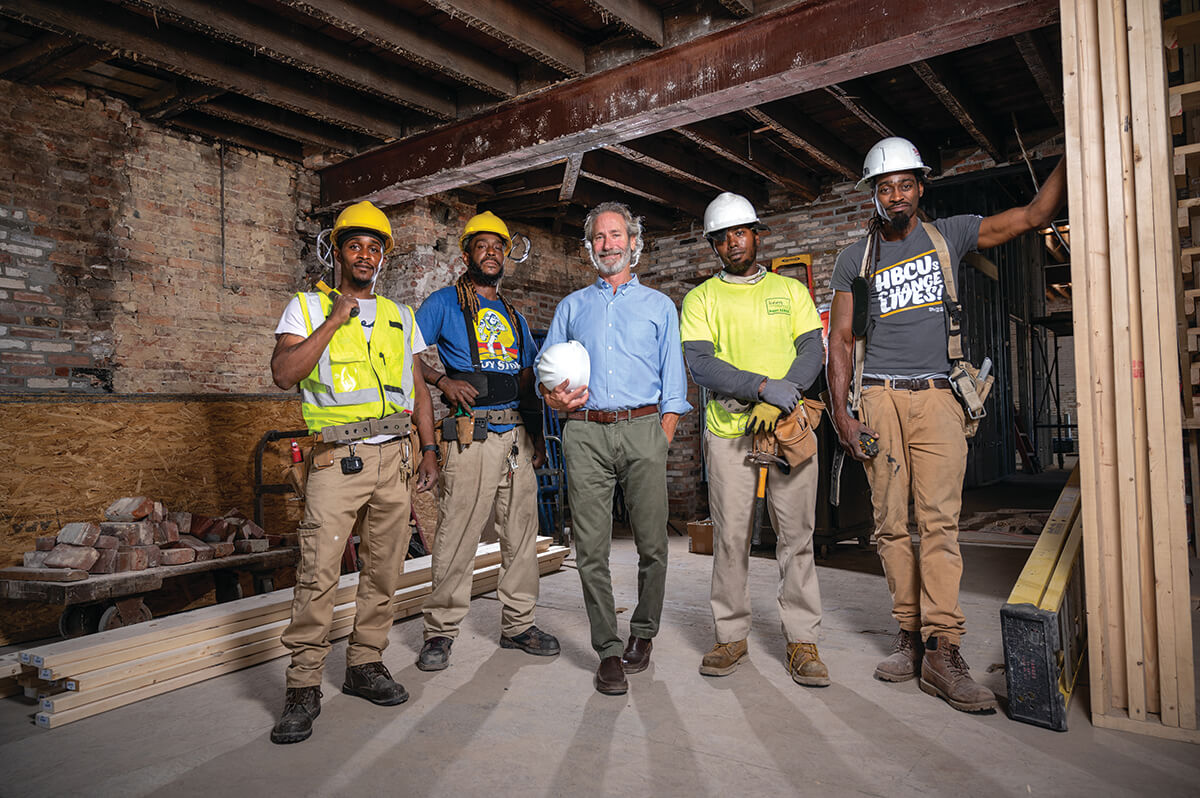

Below one window, he can watch the progress on the Mildred Belle, one of LCF’s maritime education vessels, being repaired on the organization’s marine railway. Below another, participants in the foundation’s earn-while-you-learn Project SERVE program for returning citizens—those recently released from prison—are hard at work on the nonprofit’s newest workforce development center. In the near distance are the foundation’s Crossroads charter school, one of the highest-performing middle schools in the city, and the original Harbor East campus where LCF’s first job-training program began.

“This is my life’s work,” says Bond. “I feel fortunate to have been here since the building of the The Lady Maryland.” He’s referring to a replica 19th-century Chesapeake Bay schooner he helped build with Baltimore City school kids in the mid-1980s. Back then, the program was under the auspices of an education program called the Lady Maryland Foundation, which was essentially LCF before it was LCF. “If anything, there’s more work to do now than ever and I’m pretty fired up about it,” Bond says.

Bond is humble by nature—and yes, likely tired of 61 years of jokes about his super-spy namesake—and always one to push programs, program participants, and other key leaders into the limelight, but LCF and Bond are inextricably linked.

“He’s a wonderful, hands-on, charismatic leader,” says Ron Peterson, chair of the foundation’s board of trustees and president emeritus of the Johns Hopkins Health System. “When you think of Living Classrooms, you think of James Bond.”

“This is my life’s work,” says Bond, who has been with LCF since 1986.

Bond began his tenure at LCF in 1986. He’d just returned from four years of traveling and working his way around the world. He motorcycled through Europe and North Africa, taught waterskiing and scuba diving in Corsica, backpacked through Asia, and coached lacrosse in Australia.

Eventually, he got on a sailboat and worked his way across the South Pacific, landing back in Baltimore, a place to which he never expected to return. It was then he connected with Dennis O’Brien, The Lady Maryland Foundation’s founder, and others who were building The Lady Maryland as a learning-by-doing project for youth.

“At the time, we came to the consensus to reach out to kids in the city who could benefit from this experience,” says Bond. “That’s when we really leaned in.”

By 1992, the organization had changed its name to the Living Classrooms Foundation, three years after, he was named its executive director.

The foundation acquired its Harbor East campus and built a structure to house its Fresh Start program in the early ’90s. That program, for adjudicated and out-of-school teens, teaches social and vocational skills through carpentry. Then Baltimore City asked LCF to take on the management of the city’s historic ships—U.S.S. Constellation, U.S. Coast Guard Cutter WHEC-37, U.S. Submarine Torsk, and the lightship Chesapeake—as well as the Seven Foot Knoll Lighthouse.

Each year, the organization has grown. With initial funding from a board member, LCF expanded into Washington, D.C., where it has become the largest provider of standards-based environmental education in the district. Across Washington and Baltimore, the foundation works with 25,000 individuals a year and 10,000 volunteers.

“The foundation has done everything from running lighthouses to tall ships, to running the top community center in the city in an abandoned firehouse,” says Bond. “We use these unusual venues that are natural or in the community to have a hook for kids and the community. And we have an incredibly dedicated staff focused on providing opportunities to those who may not have had what I, for example, had growing up.”

Peterson notes that even as LCF has grown exponentially, “The organization and James as leader have always been true to the fundamental mission of breaking the vicious cycle of poverty by always remembering that the work of the organization is to strengthen communities by inspiring individuals through hands-on education and job training.”

“The foundation has done everything from running lighthouses to tall ships.”

Bond says the nonprofit is always looking at its programs to make sure they are on target with its mission.

“To truly disrupt the cycle of poverty, it’s important to approach education, workforce development, health and wellness, and violence prevention—not in siloes, but comprehensively,” he says.

To that end, in 2007, inspired by the Harlem Children’s Zone, LCF designated the Target Investment Zone, a 2.5-square-mile section of East Baltimore comprising 40,000 people, 20 schools, and five public housing communities. LCF operates numerous community and workforce-development centers in the area, as well as a Safe Streets violence prevention site (one of two LCF oversees).

Bond is quick to point out that the foundation collaborates with 100 different partners in the investment zone. It’s an important part of its mission that LCF only expand where it’s been invited, rather than pushing its way in with programs Bond and his board think the community needs or wants.

That also means staying relevant to the changing needs of the community and being able to adapt, which has helped LCF survive and thrive, even during the pandemic. This is reflected in the new workforce development center, which is focused on the in-demand job sectors of healthcare and warehouse distribution, while LCF’s education programs plan to address post-pandemic learning loss.

Bond also believes in fiscal responsibility and braiding together multiple funding sources.

“We have a saying around here,” he says with a laugh. “No margin, no mission. It’s one thing to have a great idea, but it’s meaningless without money. Resource acquisition is critical.”

In its efforts to find financial support, LCF is careful not to play politics—Bond’s worked well with nine mayors and six governors. He also has a talent for cultivating a large flock of board members for LCF’s various entities, influential people with deep pockets who are fired up by Bond’s passion for the LCF mission. Bond meets with every single one every year.

“I have a relationship with each person, and we meet so I can update them, get their feedback, and ask them about how they want to get involved, or get their family or their employees involved.”

While LCF has stayed true to its core values, much has changed over the years, most notably its Harbor East home, which straddles the boundary with Fells Point. Back when the campus was in its infancy, its only neighbor was a barren Superfund site; now it’s dwarfed by corporate high rises and high-end condominiums.

Bond says he’s been offered the opportunity to move elsewhere, but he’s not interested, especially since many of LCF’s corporate neighbors have become essential partners.

“Now the campus is the hole in the donut,” he says. “It’s been very interesting to stay here, to involve people close to us in our programming, and it’s important that they see that children, teens, and returning citizens are part of the human face of the neighborhood.”

Leadership has changed as well. Early on, LCF’s senior staff was overwhelmingly white men. Since those early days, Bond says they’ve cultivated new leaders with the intention of ensuring the organization is as diverse as the communities it serves.

He says in LCF’s own way, it’s taking a “disruptive” stance on racism, too. He points, by example, to LCF’s proactive decision in 2020 to remove the name Taney from the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter in its collection. (Roger B. Taney is infamous as the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court who delivered the majority opinion in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case that said African Americans were an inferior race and could not be citizens.)

“We want those who live here to have access to education and careers and equitable access to resources so they can have peaceful, successful lives.”

The Fells Point neighborhood may be more cramped than it was 20-plus years ago, but LCF is still growing. It hopes in the near future to fund a new, 18,000-square-foot, signature building at the Washington, D.C., campus, and expand The Crossroads School to include kindergarten through eighth grade, and possibly high school.

And it’ll be looking for the resources to sustain programs in the Investment Zone, as well as funding to complete the newest workforce development center building in Fells Point. That center will have two tracks—one for healthcare and another for production, warehousing, supply chain, and distribution—as well as a café in its historic cornerstone building.

One bit of assistance came after the state legislature allocated $2.5 million for the foundation to haul the Constellation into dry dock for essential repairs. In true LCF fashion, some of the work will be done by Project SERVE participants. Bond says the need for resources and programming to combat the city’s challenges is greater than ever. There are more returning citizens leaving prison, more kids on the street in need of constructive programming. But he’s certain LCF has made a measurable difference in many lives, and he’s excited to continue contributing as long as he’s able.

“I feel so fortunate to have been here since The Lady Maryland, to have brought in talented young leadership, and to be a conduit to those who have resources so our organization can excel at providing high-quality programming and sustain the historic ships and shipyards for future generations,” he says. “We want those who live here to have access to education and careers and equitable access to resources so they can have peaceful, productive, and successful lives.”