By Jane Marion

Photography by Mike Morgan

On a quintessential cool and crisp October morning, Victor and Lynne Brick stand in shavasana, or resting pose, as they finish up their morning yoga class with a private instructor inside their newly built labyrinth. The labyrinth—an elaborate, winding gravel path with stone borders—faces southwest, says Victor, because, particular to their property, that direction channels positive energy and a sense of well-being. Indeed, this is the spot where they center themselves and meditate before the beginning of a busy day.

Morning exercise is followed by what Lynne calls a daily “two- sipper” swig of Veuve Clicquot mixed with orange juice and poured into a Planet Fitness-branded Champagne flute as a way of welcoming the day.

“So many people wait to drink mimosas when they’re on vacation,” says Victor. “So we have this tiny little mimosa every morning because it’s a celebration. It’s a sign to ourselves and to the universe—we celebrate life. L’chaim,” he says, invoking the Jewish toast meaning “to life.” “It’s just a tiny symbol.”

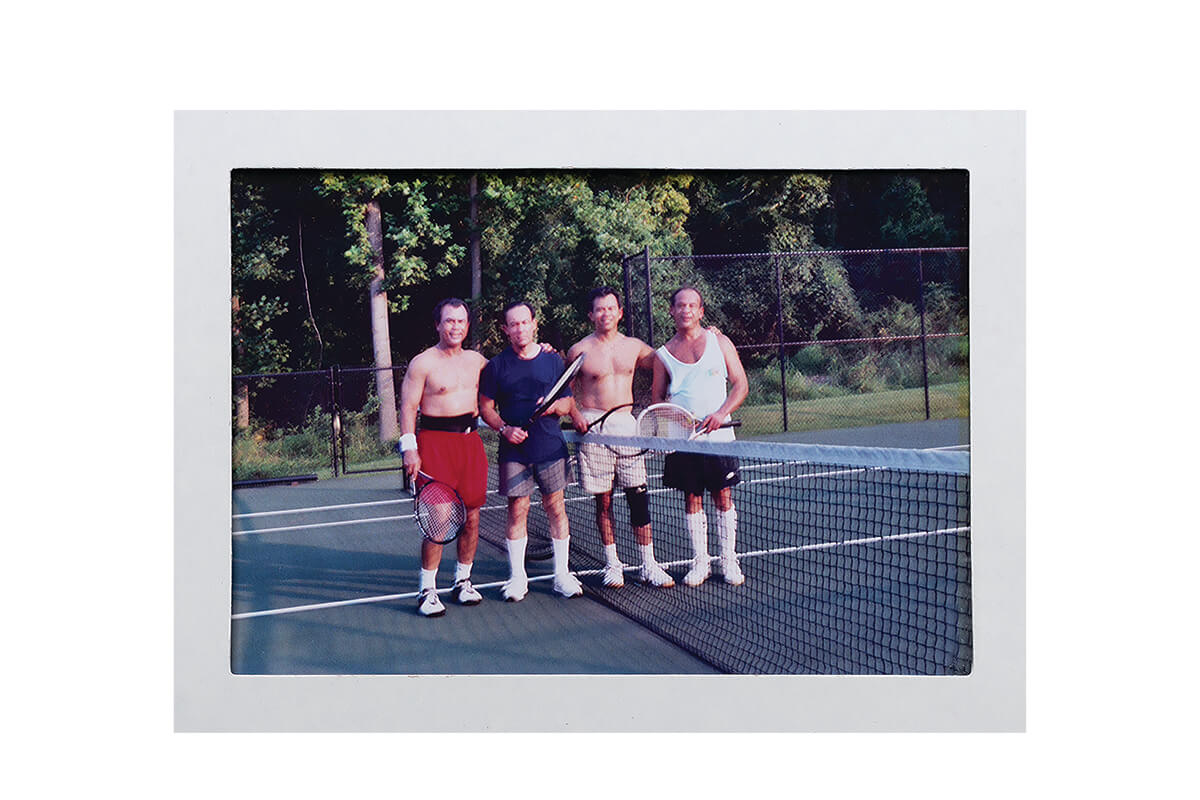

Though they spend most of their time at an oceanfront South Beach, Florida, condominium, their palatial Timonium brick (of course) family home, with its soaring Corinthian columns, a large deck and hot tub overlooking six acres, a home gym, an Infrared sauna, a pool, and a tennis court, is something of a touchstone. It’s also where they spent the height of the COVID-19 outbreak. And getting the labyrinth built was one of their pandemic projects.

“We turned our sunroom into a yoga studio, did yoga on the deck, we swam, we played tennis, and we got back into our routine,” says Victor. “We made this our health club.”

For the Bricks, whose fit physiques, glowing complexions, and preternatural perkiness belie their age—he’s 69; she’s 66—it’s all about living a healthy (albeit wealthy) lifestyle. And they embrace it all, whether that means drinking protein shakes packed with collagen powder, turmeric, coconut water, almond milk, matcha, cacao, and other ingredients, or taking a custom combination daily of some 20 or so botanically based supplements based on their bloodwork and recommended by master herbologist Donald Yance.

“We don’t do guesswork,” says Victor, as Lynne loads collagen powder into the mixer. “We try, whenever possible, like everything we do in life, to quantify and maximize our results.”

And that also includes meeting with their feng shui guru, Hope Gerecht, whom the couple consults “on almost every major decision we make,” says Victor. “We ask Hope for her input on all things. She’s the one who determined the direction the labyrinth or the fountain outside our house should face, or which way we should face when we sign agreements, and which times are most advantageous to us for making business decisions, that kind of thing.”

While their devotion to self-care might sound a bit extreme, there’s a purpose behind their passion.

“The key is to die young, as old as possible,” jokes Victor, whose full name is C. (Charles) Victor Brick. (“Lynne thinks the ‘C’ stands for control,” cracks Victor. And yes, Brick is his real last name.)

“We do more in a day than most people do in a month, and the only way we can do that is to take care of ourselves. We built this house to nurture us so that we can do everything we need to do—we have so many people counting on us that we cannot fail.”

Suffice it to say that both Bricks, who met in 1974 while still students at Towson University, have always been the picture of health. In fact, they met at Burdick Hall, the gym on TU’s campus, where he was playing indoor basketball and she was walking with a group of girls on her way to dance practice.

“She walked through, and someone whistled,” Victor recalls, “and she turned around and smiled instead of ignoring them. She was the only one who smiled. I said to my friend, ‘See that girl? I’m going to marry her,’” Victor recounts. “I’d never seen her before, but it was that look in her eye. I was looking for a hardheaded woman.” (For her part, says Lynne with a laugh, “I wasn’t looking.”)

“I really felt that I needed a partner who could help me accomplish my greatness,” Victor says, “even though I had no idea what that would be at the time.”

FOR THE BRICKS, WHOSE PRETERNATURAL PERKINESS BELIES THEIR AGE, IT’S ALL ABOUT LIVING A HEALTHY LIFESTYLE.

That journey toward greatness began in earnest in 1985, when the Bricks founded Brick Bodies, the first of their eponymous gyms that tapped into the fitness-fueled zeitgeist of the times—think: aerobics, leg warmers, spandex—and helped them build an empire in the Baltimore area. In fact, by 1998, Self magazine deemed the duo “one of the foremost fitness couples in the country.”

While their local gyms were a huge success, the Brick Bodies brand was not known beyond these borders.

“It wasn’t scalable,” says Victor. So, the ambitious entrepreneurs turned to investing in Planet Fitness, the no-frills, low-budget centers whose “Judgment Free Zone” welcomes all shapes and sizes. By 2008, the couple started building Planet Fitness gyms at warp speed, initially, averaging 10 new clubs a year. To date, the Bricks own 82 Planet Fitness gyms (from Washington, D.C., to Washington State and even nine in Australia), making their centers the largest privately owned franchises in the system. In total, their Planet clubs boast 600,000 members (“almost the population of Baltimore City,” Victor notes).

To focus on their Planet franchises, in 2015, they handed the reins of Brick Bodies to their now-40-year-old daughter, Vicki Brick Zupancic, a former Division 1 and international basketball player, naming her CEO.

Their hard work has made them successful beyond their wildest dreams, which is also why they feel it’s so important to give back. In addition to running the gyms, they have donated their time and talents—and a small fortune—to the John W. Brick Mental Health Foundation, which they founded as a way of honoring Victor’s oldest brother John, who died of complications from schizophrenia.

The Bricks say that they see giving back as yet another path to wellness. “Giving back is part of our DNA,” says Lynne. “Giving…is a sign of gratitude. And the more you give, the more you get—it feels good to give.”

Victor circles back to a favorite story in the Bible to bring home the point about sharing one’s fortune when you’ve been lucky enough to acquire one.

“There’s the story of the rich man who came to Jesus and asked what he could do to get in the Kingdom of Heaven,” says Victor. “And Jesus said, ‘Sell all that you have, give it to the poor, and follow me.’ And the man went away despondent for he was a rich man and had many possessions—people want to do it, but they just can’t. And then every now and then someone takes a stand for something. And they are the ones who change the world.”

This story resonates with Victor and Lynne personally—if you have something, give it away, make a difference, take a stand for something, and change the world along the way…

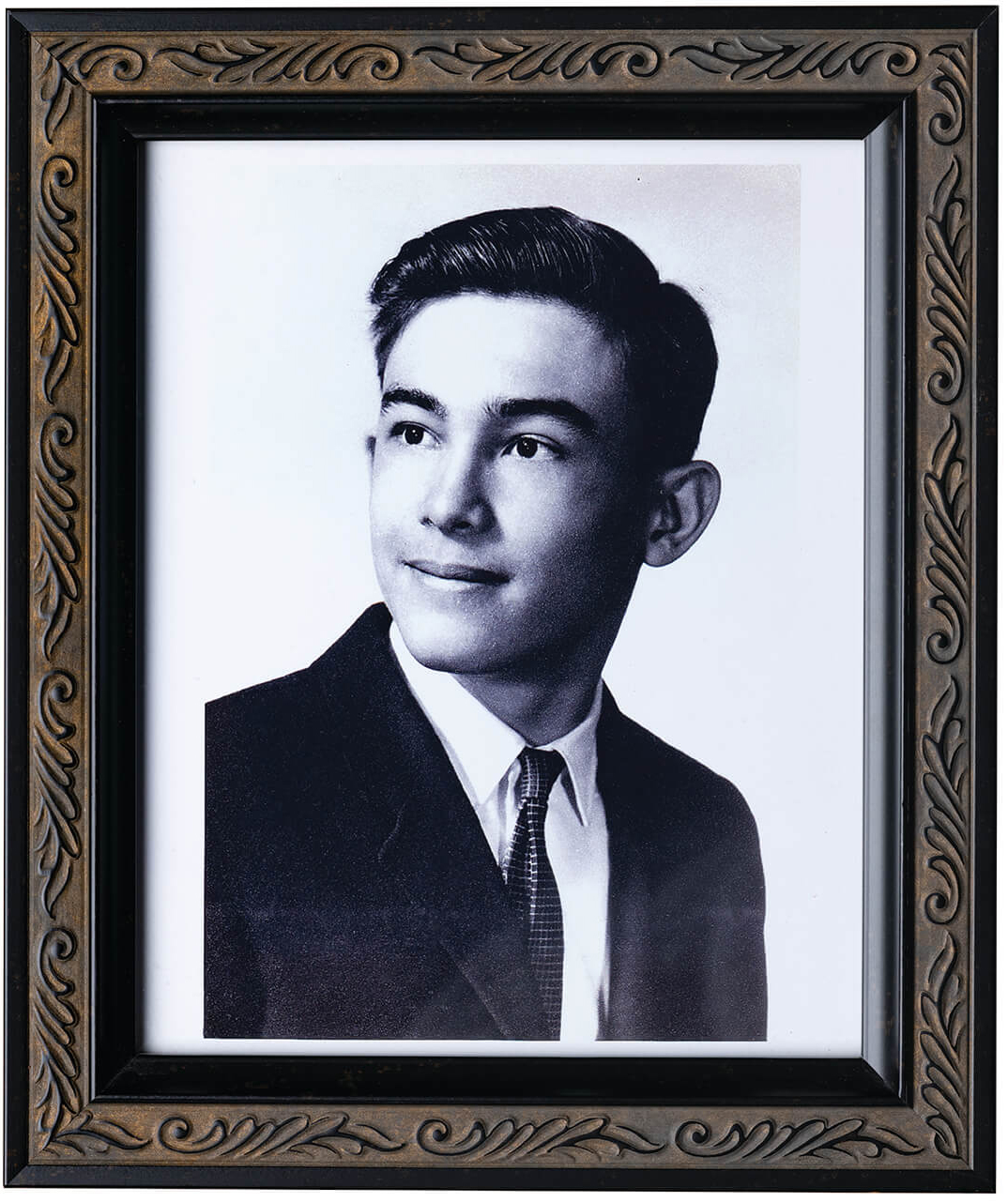

Despite outward appearances, life has not been all Champagne wishes and caviar dreams. Victor was born in Okinawa, Japan, to a Filipino mother and an American father, the fourth of five children. He spent his early years in Honolulu. When Victor was eight, his family moved to Silver Spring, where his dad, a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army, worked for the Navy’s Bureau of Yards and Docks, and later the Washington Area Transit Authority, supervising the acquisition of real estate for the subway system.

When Victor was in middle school and his brother John was in high school, John was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Later, when his youngest brother, Bob, was in college, he, too, was diagnosed with the rare disease that strikes roughly one percent of the world’s population. “The NIH wanted to study the family and their genetics,” recalls Lynne.

Victor found solace and salvation through sports, first at Silver Spring Boys Club, then Silver Spring’s White Oak Junior High, and Springbrook High School. Athletics offered an avenue, at a time when anti-Asian sentiment ran high.

“We were people of color in a totally white community, not long after WWII. Sports were a way for us to prove ourselves—and we proved ourselves very well,” says Victor. “My brother Merrill played football and basketball and ran track, I played basketball and ran track, and John was a runner.”

Despite their heartache, the stress, and, in Victor’s words “constant crisis management,” the Bricks stayed strong as a family unit.

“We are firm believers that tough times don’t build character, they reveal it,” says Victor, his background as a motivational speaker evident in almost everything he says. “John pulled our family together. We rallied around John because of my parents. I saw how my mother was devoted to John every bit as much as she was to Merrill and me—and I followed suit.”

It was difficult for Victor. There was one time when he had to come to the rescue when Bob landed in jail after a psychotic episode in Canada. And he struggled watching John wreck car after car, unable to hold down a job, occasionally finding himself homeless. Nonetheless, Victor lights up when he talks about his brothers.

“John was always different,” he says. “He was always socially inappropriate, and I rarely ever remember him being happy, but he was brilliant, and he passed on his love of reading and history to me. He wrote this short story once, and I’ll never forget, he described this character as ‘marvelously gifted and tragically flawed’—that was my brother. I took all the great things from him, and I learned from them—and I tried to help him with his flaws.”

Through the turmoil, Victor says, it was Lynne, a former nurse at the R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center at the University of Maryland, who was his “rock.”

“I understood that it was mental illness,” says Lynne. “And with my nursing background and my DNA to care for other people, I knew that he couldn’t help it. When he had his issues, everyone in the family rallied—and I was part of the rally team to surround John with love.”

Victor and Lynne encouraged John to live a healthy lifestyle, as a companion to his medical care. “He didn’t get support or encouragement in that direction, not from the medical profession and not even from my parents, because that wasn’t deemed as very effective or important,” says Victor. Adds Lynne, “We tried to help John with lifestyle choices, getting sleep, exercise, nutrition—those were things he could have control over, but it got to a point where he refused to listen.”

By 2005, John was 62 years old and living in a trailer park in Port Orange, Florida, just outside of Daytona Beach and three miles down the road from his parents. “He began to withdraw from society and from contact with the outside world,” says Victor.

As John slipped deeper into psychosis, he began to believe that his illness was his punishment for sinning. “He blamed himself and felt he needed to do penance, and one of the ways he tried to absolve himself was to eliminate all the conveniences of modern life,” says Victor. “He had no radio, no television, then he got rid of the refrigerator, and then you’d go to see him, and he wouldn’t come out and would have to talk through the door. Finally, he got rid of an air conditioner in a metal trailer home in Florida in the middle of summer.”

On June 13, 2009, Victor’s father found his son’s body on the floor of that trailer. The temperature inside was 115 F.

“We think he died of heat stroke or a heart attack,” says Victor. “My mother refused to do an autopsy, but it was really schizophrenia that killed him. He fought it to a point and then gave up—that was the saddest thing for me, to see my brother give up.”

A few days later, at John’s funeral, as the family gathered inside the church, something shifted inside Victor. “I was just overwhelmed with emotion,” he recalls. “I was weeping inconsolably in the church. I looked around the church and there was no one to weep for my brother but my mother and our family. It was so sad. He was this beautiful person and yet he passed, and no one even knew that he existed. It was at my brother’s funeral that I said, ‘I will make sure they remember John and that others don’t have to go through what we are going through.’”

“WE ARE FIRM BELIEVERS THAT TOUGH TIMES DON’T BUILD CHARACTER, THEY REVEAL IT.”

True to his word, to honor his beloved brother, by 2015, the Bricks launched the John W. Brick Mental Health Foundation. Since that time, the money they’ve donated has gone to running the operations of the organization, “so we have no overhead,” says Lynne. “And we will continue to make substantial personal contributions so all funds raised will go to research, programming, and services,” says Victor, who shies away from saying how much they’ve given, though it’s a considerable sum.

The foundation has a simple but lofty aspiration: to “put a dent in the universe,” in Victor’s words, and change the way the world treats mental health.

To that end, the foundation has taken a broader salutogenic, wellness-based approach to mental health (as opposed to pathogenic, which is illness-based)—including exercise, nutrition, and mind-body practices such as meditation—and integrating it along- side more traditional treatments like medication and therapy.

To hep run the foundation, in 2019, the Bricks hired Cassandra Vieten, a clinical psychologist and a leader in the field of mind-body research, as executive director.

Despite research that has proven that mind-body practices can change the physiology of the brain, the research has been long-ignored, says Vieten.

“We believe that mental health is an ecosystem,” she says. “If you look at it, many different things impact our mental health: nutrition, body movement, spirituality, meaning, and purpose…and yet when we go for mental health care, most of that is never brought up. We think this is not just an optional cherry on top of the sundae. [The mental health profession is] using a very rudimentary and narrow approach to addressing mental health—and it’s to our detriment.”

Since its founding, the foundation has taken on major projects, including awarding a $1.2-million grant to the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), for a landmark study on the effects of “positive stress” (also known as good stress or eustress, which releases endorphins) on mental health.

“We tested women with either high stress or depression and tested the effects of high-intensity interval training, breathing techniques, and meditation,” says Elissa Epel, a professor and vice chair of adult psychology in the department of psychiatry at UCSF, which was the recipient of the grant. “What we found is that those things improve stress resilience. While we can’t eliminate stressful events from our lives, if we have a more positive [reaction], it serves as a buffer from the effects of stress.”

In addition to awarding the grant, the foundation created a seminal report, the Move Your Mental Health Report, to review the results of more than 1,400 scientific studies about the effect of movement on mental health, conducted over 30 years.

The conclusion? Exercise should be a part of a treatment plan for anyone with depression and anxiety. As a result of the report, there’s now an interactive database on the foundation’s website, for anyone to use, be it mental health professionals, policy makers, or families.

“These projects will give people a road map of what to do to improve people’s mental well-being, not just for those who have mental illness but for anyone,” says Victor. “For instance, if you have anxiety, you might need to do something more calming like yoga or qigong; if you’re depressed, cardiovascular exercise or structured group exercise is better for you. Our database will tell you that.”

Closer to home, the John W. Brick Foundation also awarded a grant to The Johns Hopkins Hospital, to donate equipment for an exercise room on the adolescent floor where John was an inpatient many years ago, and installed a fitness center at Arundel Lodge, a behavioral health center in Annapolis with a variety of support services. They’ve also given a significant grant to the National Center for Healthy Veteran’s Valor Farms, a residential integrative wellness center in Lynchburg, Virginia, for veterans suffering from PTSD.

“MANY DIFFERENT THINGS IMPACT

OUR MENTAL HEALTH: NUTRITION, BODY MOVEMENT, SPIRITUALITY, MEANING, AND PURPOSE.”

The foundation has an international presence as well. For the past two years, the John W. Brick Foundation has partnered with The Never Alone Summit, in collaboration with the Deepak Chopra Foundation’s #NeverAlone initiative, to produce a global gathering to support mental health during the pandemic. One hundred and twenty thousand people from 70 countries participated.

Alongside such luminaries as Chopra, aerospace surgeon Yvonne Cagle, and Surgeon General Richard Carmona, Victor and Lynne spoke together at the three-day summit, one of the largest gatherings of mental-health professionals, wellness experts, and brain scientists ever. There the Bricks received the prestigious Global Wellness Summit 2020 Debra Simon Award for Leadership in Mental Health for their work with the foundation.

“It was very rewarding,” says Victor. “It was a landmark event that indicated to Lynne and me that the foundation had arrived on the international stage—and that we were making a difference.”

As for the foundation’s future, the first six-and-a-half years have just been a warmup for what’s to come. “We have big plans,” says Vieten. “We’re just getting started,” adds Lynne.

In 2022 alone, the Bricks will fund several major scientific studies. Additionally, the foundation has provided a large grant to the Baltimore-based Holistic Life Foundation, a nonprofit organization that incorporates mind-body practices for children and adults in underserved communities. In May, the foundation will play a role in a summit featuring athletes and entertainers who have struggled with mental health.

Victor emphasizes that the foundation is not promoting the idea that exercise or meditation can replace the clinical treatment of one’s mental health, only that it should serve as a complement.

“We’re not advocating you don’t need meds,” says Victor, who, along with Lynne, is a member of the board of advisors for the Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Science. “We respect the medical profession and the role it plays, but we are saying there’s a continuum—medicine is meant to eradicate disease. Holistic processes are meant to either prevent it or stabilize it once it’s gone. We are looking to blend the two.”

Medical professionals such as James Potash, director of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Johns Hopkins Medicine, are impressed by the Brick’s efforts.

“They have pushed us to think hard about the relationship between physical health and mental health, and that’s a valuable thing for us to keep front of mind,” he says.

Experts such as UCSF’s Epel believe that the foundation fills a void in the treatment of mental health. “This foundation is in a league of its own, because it is funding strategic research that is much needed to show the benefit of integrative strategies for mental health,” she says. “There’s no other foundation like this in this space—they are leading the field.”

In many ways, Victor’s youngest brother Bob, now 66, is living proof of how someone who struggles can benefit from healthy lifestyle choices. Thanks to support from his brother Merrill and Merrill’s wife, Sherry, Bob regularly rides a bike; works out at his local Planet Fitness in Florida; lost 60 pounds as the result of following a low-carb, low-sugar healthy diet; and is able to hold down a part-time job and live on his own, while also staying compliant with therapy and medication. He has even been able to dramatically reduce his medication dosage.

“He is flourishing,” says Victor, smiling. “If I called him now, he’d be happy.”

In the meantime, the Bricks continue to open Planet Fitness gyms, the success of which is inextricably linked to their foundation work. “I do the business at the beginning of the week and the foundation at the end of the week,” says Victor, “because without the business, the foundation doesn’t exist.”

While in Baltimore in late October, Victor and Lynne were off to the grand opening of two new Planet Fitness clubs, one in Elkridge and another in Ellicott City. In the following weeks, they opened two new clubs in Tennessee and one in California. By December, they had opened two more gyms in Australia, one more in Washington state (and yet another in Australia at the beginning of the new year).

“We divide our time to something like 70 percent to the gyms and 30 percent for the foundation,” says Victor. “We go to grand openings, and we try to get to every club every year.”

It’s a lot to juggle, but like everything they do, it’s a winning strategy.

“They are simply remarkable people,” says Epel, “and together, an even more remarkable couple. They walk the talk and live their own lifestyle of well-being and spreading contagious, positive emotion. They have big, generous hearts and an equally grand vision to match it. It’s remarkable what they have accomplished.”

Getting into the Kingdom of Heaven can wait, but for the ever-beneficent Bricks, entry seems all but certain.