News & Community

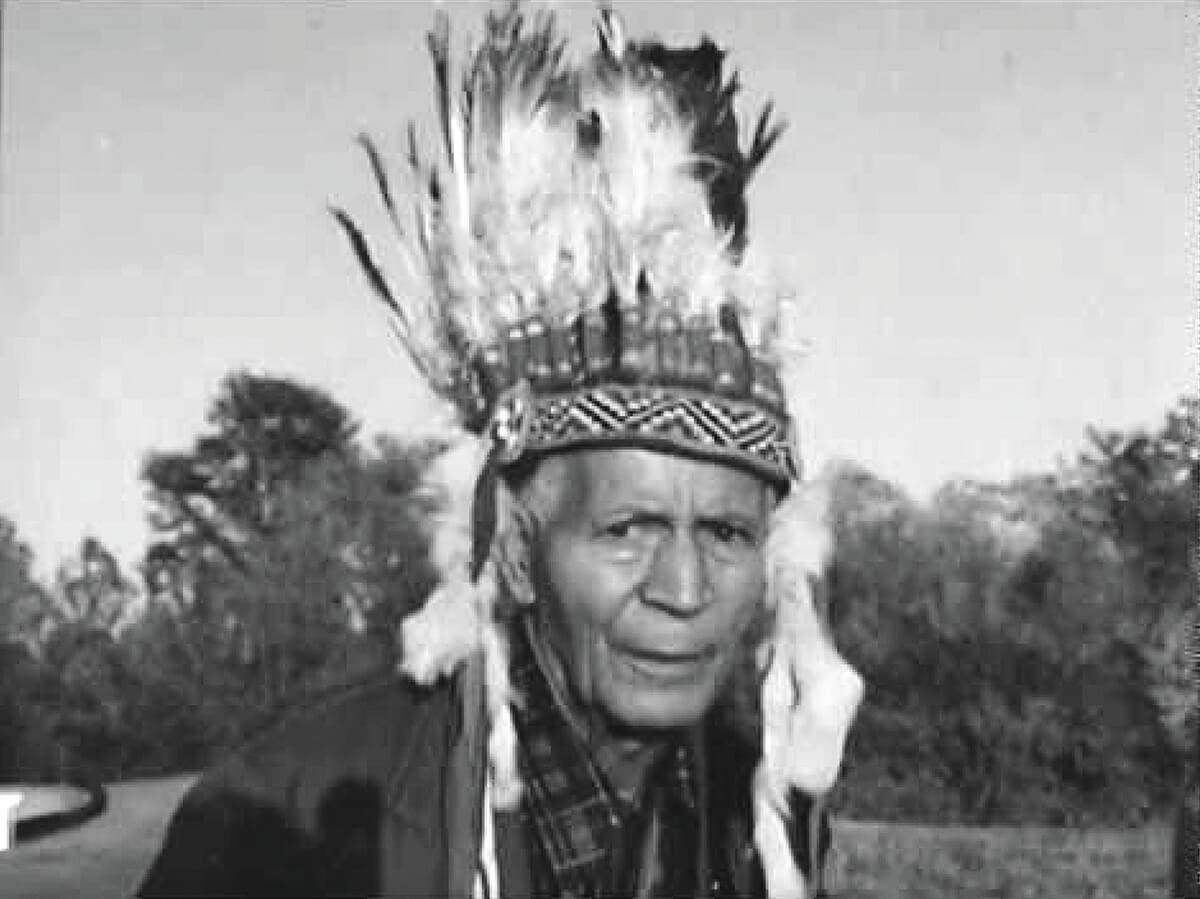

TURKEY TAYAC TOOK HIS LAST SWIM in his beloved Potomac River in the late autumn of 1978. Born in 1895, the 27th hereditary chief of the Piscataway Indian Nation grew up fishing and crabbing in the tributaries of the Chesapeake, as his ancestors had done for millennia, mastering how to make hooks from catfish bone. Mostly, though, he came to cherish the Potomac, the fourth-longest river on the East Coast. He read and understood its rhythms, walking familiar wooded paths to its shoreline for his ritual swims.

Even in his 80s, he swam from March to November, believing the river’s often-chilly water held healing powers long before cold plunges became a wellness trend. He was probably right. He lived more than 60 years after nearly dying from exposure to mustard gas during World War I combat in France.

A month after that final November swim, his immune system weakened by previously undiagnosed leukemia, he died in a Veterans Administration hospital from a viral lung infection. After returning home from the war, he’d worked for the Internal Revenue Service and then as a laborer for State Roads Commission, where he retired at 70. But he had always stayed close to the land in Southern Maryland, eschewing modern conveniences and frequently camping, living off plants, berries, herbs, root vegetables, and the fish he caught. His anglicized name was Phillip Proctor, but he remained one of the very last who grew up with first-hand knowledge of his Indigenous nation’s language and traditions.

A grassroots activist and organizer decades before the American Indian Movement of the 1970s, Tayac traveled up and down the East Coast on behalf of Indigenous causes. But he held a special concern for Moyaone, for centuries the historic capital of the Piscataway, situated on the Potomac’s eastern shore along the Prince George’s and Charles County border. A dig there led by University of Michigan archaeologists and Smithsonian researchers in the 1930s revealed Indigenous human habitation dating back 6,000 years. Later evidence indicated Native Americans had been present in the area much longer, between 12,000 and 15,000 years ago. Ossuaries dug up at the village contained the remains of more than 1,000 Indigenous people—relics that Tayac and tribal members later fought to recover and rebury.

Moyaone represented the largest and last Piscataway major settlement before the arrival of the Ark and the Dove, the 400-ton merchant vessel and 40-ton pinnace that brought the first 140 colonists to Maryland in 1634. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964, today Moyaone is located within Piscataway Park, part of the National Park system.

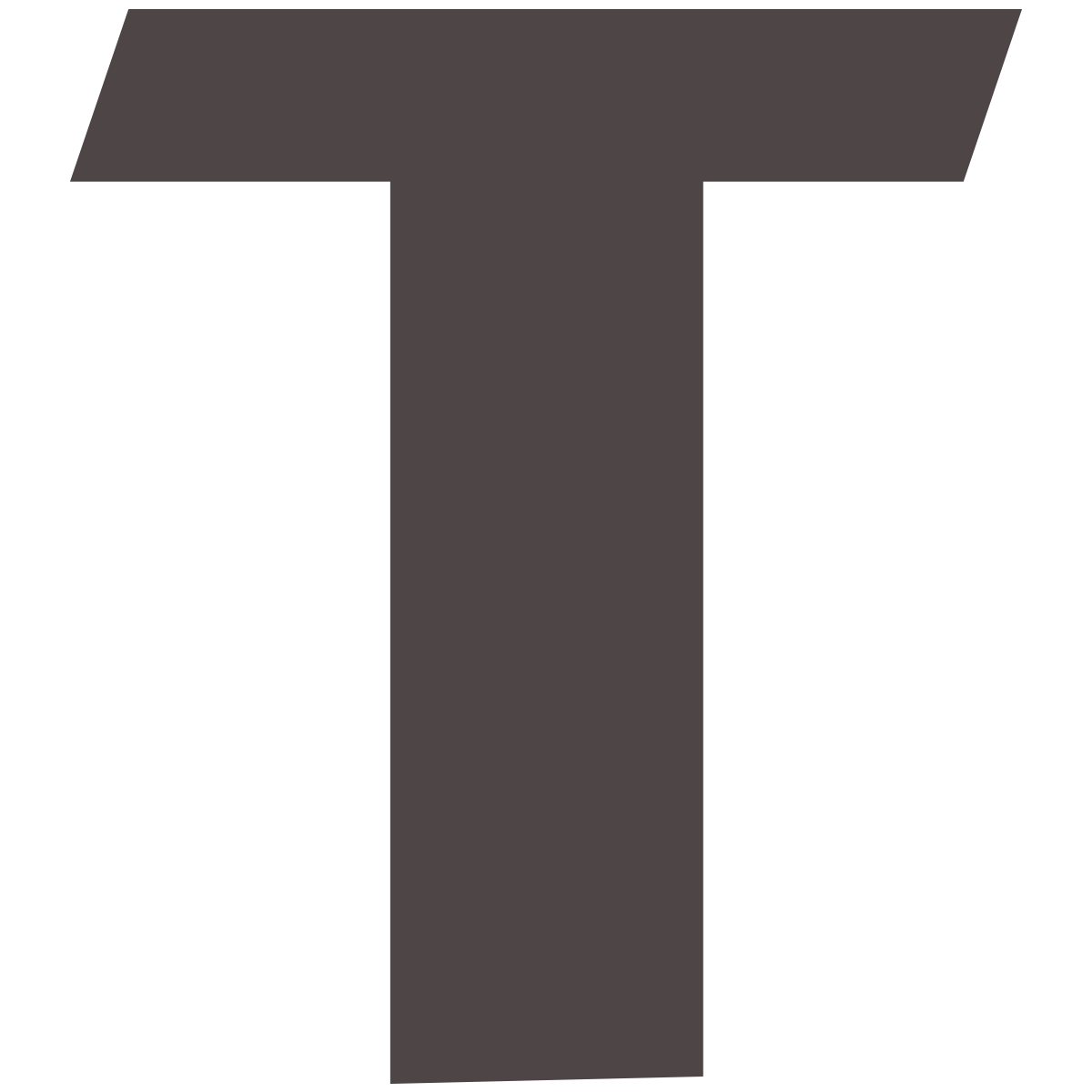

Tayac supported the creation of the park on sacred Piscataway land with two conditions: that he could be buried there, and that members of the tribal community could visit freely for cultural and spiritual purposes. However, because there was no written record of what had been a handshake agreement with then-Secretary of Interior Stewart Udall, he was not interred at Moyaone until 1979, a year after his death, when Congress passed legislation, permitting his burial on the federally controlled property.

“I’m a Piscataway,” Chief Tayac once told The Baltimore Sun. “There are not many left. Practically all have lost their identity. But some knowledge was handed down by word of mouth and is just in me. I sat around fires and listened to stories and must have a right good remembering.”

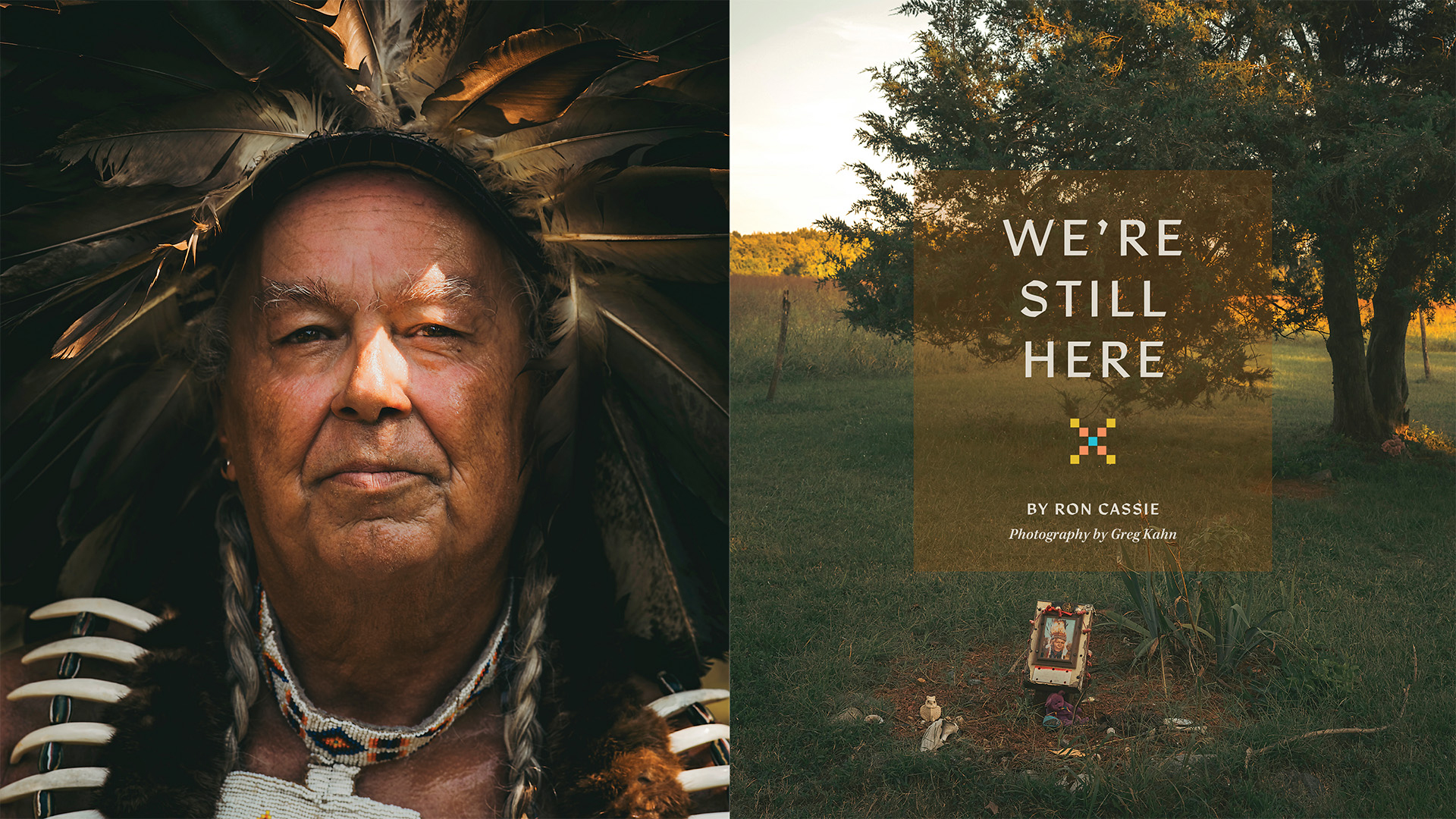

ABOVE: TRADITIONAL DANCE PERFORMED IN HISTORIC ST. MARY'S CITY. OPENER: PISCATAWAY INDIAN NATION CHIEF MARK TAYAC, BURIAL SITE OF HIS GRANDFATHER, TURKEY TAYAC.

t the beginning of the 17th century, the Piscataway, or “the people where the water blends,” were the most populous nation in the lands between the Potomac River and Chesapeake Bay, with at least 7,000 people, and possibly many more, among its member tribes. They cultivated the “three sisters”—corn, beans, and squash—a staple of their intercropping agricultural practice and their foodways, which included fishing, gathering, and hunting. They lived in longhouses and dug canoes from tree logs, held seasonal festivals, practiced decorative arts, and maintained a rich spiritual life tied to their ancestors and the land. Their territory extended from present-day Southern Maryland, north to Baltimore County, and west to the Appalachian foothills.

Unifying smaller tribes into a confederacy around 1,200 C.E., current Piscataway Indian Nation Chief Mark Tayac, the grandson of Turkey Tayac, says, “[Piscataway] history intertwines with the very fabric of Maryland. We have a beautiful state and beautiful waterways, but just look at who they are named after.”

To his point, consider how much of the state’s iconic geography bears the names of the tribes that once resided there: Assateague Island; the Chesapeake Bay; the Allegheny, Appalachian, and Catoctin mountains; the towns of Pocomoke and Tuscarora, Wicomico County, Piscataway Creek; and the Anacostia, Choptank, Monocacy, Nanticoke, Patapsco, Patuxent, Potomac, and Susquehanna rivers; to name a few. Port Tobacco, where Tayac resides, takes its name not from the colonial cash crop, but from the Potapsco tribe.

Tayac, who also heads up the Piscataway Nation Singers & Dancers, presenting educational powwow-style events and performing songs and dances passed down from his grandfather, notes an interesting juxtaposition at the same time. “Today, when you look across the Potomac River from the village of Moyaone, you see George Washington’s home, Mount Vernon.”

He and members of the surviving Piscataway nation want Marylanders to know their still-evolving story, too.

OIL PAINTING OF JESUIT

ANDREW WHITE MEETING

NATIVE PEOPLE.—COURTESY OF THE MD CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE

he Spanish were actually the first Europeans to arrive in the Chesapeake region, but they failed to establish a Catholic mission and left. Jamestown, founded by the English in 1607, marked the first permanent European settlement in not just what we now call the DMV, but North America. It was home to the Powhatans and, famously, Pocahontas. (The real-life Pocahontas was initally kidnapped by English settlers and held for ransom.) In 1608, Jamestown colonist John Smith explored the Bay and the Potomac, visiting Moyaone and depicting it on his detailed map, which survives to this day. Smith sailed the Patapsco, too, noting the tidal basin of the future Inner Harbor and the flanking “great red bank of clay” that is Federal Hill. Smith also memorably remarked that the oyster reefs in the Bay were so prominent, ships had to navigate around them, and everywhere, wild oysters, now scarce, “lay as thick as stones.”

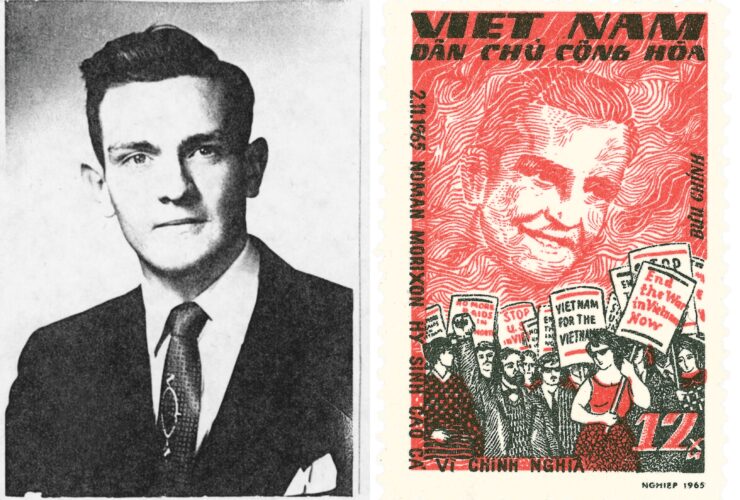

Twenty-seven years later, when the Ark and Dove arrived in what would become St. Mary’s County, their notable passengers included Leonard Calvert, the first proprietary governor of Maryland, and Jesuit priest Andrew White, whose translation of the Ten Commandants into the Piscataway language also survives.

TURKEY TAYAC, THE 27TH GENERATION OF THE HERIDITARY CHIEFS OF THE PISCATAWAY, FOUGHT TO BE BURIED IN MOYAONE, THE TRIBE'S ANCESTRAL HOME, NOW A PART OF PISCATAWAY NATIONAL PARK.

Not surprisingly, the 28-year-old Calvert and colonists were greeted with suspicion when they dropped anchor at St. Clement’s Island in the Potomac, not far up the mouth of the Chesapeake. But the Piscataway did allow the strangers to build a nearby settlement in the territory of the Yaocomaco, a small tribe under their umbrella—having no way of anticipating the exponential numbers of English invaders, guns, and diseases that would follow.

The English, of course, were not content to occupy just one small parcel in what is referred to as Historic St. Mary’s City. The Calvert family had been handed a charter from King Charles I for the whole of the Piscataway’s land, plus that of Native people of the Eastern Shore, and Central and Western Maryland. Ultimately, St. Mary’s became the fourth-oldest permanent English settlement in North America, but contrary to how the story has been mythologized, relations were fraught, often confrontational, from the beginning.

Armed conflict had begun by 1639 when Gov. Calvert launched a military expedition against Native people on the Eastern Shore and declared war against the Piscataway tribe of Maquantequats. In June 1642, he ordered that Native people could not be sold guns or ammunition, and weapons be provided to all settlers “able to bear arms.” That September, the Susquehannock, Wicomico and Nanticoke were declared “enemies to the province.”

Conflict continued as the English kept encroaching on Piscataway villages, farmland, and hunting grounds. A 1652 treaty with the Susquehannock, who were being pushed south amid pressure from Pennsylvania colonists and the Iroquois, took Piscataway land on the Western Shore and in Central Maryland and signed it over to Maryland colonial authority—though it doesn’t appear it was the Susquehannock’s to give away.

Further expansion and English population growth led to the first treaty in 1666 between Maryland’s colonial government and the Piscataway. Known as Articles of Peace and Amity, it established rights for Indigenous people to hunt, fish, and crab, and set aside reservations, or manors, as they were called. It also required Native peoples to immediately lay down any weapons if they encountered English settlers—lest they be legally shot and killed. Other treaties followed. All were trampled in the end.

The simple fact is the onslaught and genocide that transpired across the continent—waves of settlers, smallpox epidemics, broken treaties, militia campaigns, Christian conversion, the creation of reservations, the relentless theft of land—occurred in Maryland two centuries before the Trail of Tears and Plains Wars. By the 17th century’s end—in the span of a single lifetime—the Piscataway language, ways, and people had been all but erased. Once-thriving tribes like the Susquehannock were gone as well.

For the past 110 years, March 25 has been celebrated as Maryland Day, a state holiday commemorating the arrival of the Ark and Dove.

“It is not a mixed-blessing or double-edged sword moment for us,” says Gabrielle Tayac, a public historian, George Mason University associate professor, and granddaughter of Turkey Tayac. “It’s a single-edge sword. But we’re still here.”

INDIGENOUS

HERITAGE DAY IN

HISTORIC ST. MARY'S.

he is right, obviously. Somehow, small bands of Piscataway endured. One contingent, possibly 300 in number, fled Maryland and its colonial government, which had closed its reservations and revoked all its claims for land, for a site called Conejoholo in Pennsylvania. There, they became known as the Conoy and Piscataway Conoy. Others migrated farther north, joining the Six Nations of the Iroquois, where Piscataway descendants still live on the Grand River reserve in Ontario, Canada. A few eventually migrated back from Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the Ohio Valley, alternately keeping their distance from white authorities and assimilating into Southern Maryland life.

And a handful of families stayed and persevered, intermarrying with the descendants of white indentured servants and free Blacks, becoming farmers and maintaining ties with St. Ignatius Church in Port Tobacco—one of the very oldest continuously operating Catholic parishes in the United States, founded by Andrew White. A stained-glass window inside the church commemorates the baptism of Piscataway “Indian King” Kittamaquund in 1640.

Ironically, centuries later, Catholic birth and baptismal records provided important genealogical information for contemporary Piscataway communities in their long effort for state recognition. In contrast to governmental documents that removed Indigenous identities—census records that categorized Piscataway under “mulatto” or “Negro”—St. Ignatius was among the Catholic parishes that consistently recorded their Native members as “Indian,” regardless of mixed heritage, in accordance with their tripartite, segregated pews.

In fact, after decades of expensive expert historical and genealogical research, it was not until 2012 that the state of Maryland formally recognized the Piscataway Indian Nation and the Piscataway Conoy Tribe, currently led by tribal chair Francis Gray. (The two Piscataway groups have had a fractious relationship since the death of Turkey Tayac, but it is improving.) The year 2012 was not arbitrary. Rejected by Gov. Parris Glendening in 2000 and Gov. Robert Ehrlich in 2004, Maryland recognition of the Piscataway was withheld until after state casino gambling legislation had been signed into law and licensing rights had been granted to non-American Indian parties.

In the case of the Piscataway Conoy, the tribe was forced to renounce any plans to open casinos as a condition of receiving state recognition. And, notably, when then-Gov. Martin O’Malley issued his executive orders separately recognizing the Piscataway Indian Nation and Piscataway Conoy Tribe, the decree explicitly stated their new status did not grant any “special privileges” related to gaming—or land entitlements.

Nonetheless, at a State House ceremony attended by tribal leaders, some in ancestral clothing, and accompanied by the sound of drums, O’Malley struck a celebratory tone. He described the process as not just one of “reconciliation” and a day “380 years in the making.” He thanked the Piscataway for their “forgiveness” and their generosity, “often betrayed,” with which their ancestors had greeted the settlers aboard the Ark and the Dove. For their part, tribal leaders celebrated the step forward, thanking the governor and giving him gifts, including tobacco and the promise of arrows, commemorating the gift given when the tribe signed its last treaty.

To receive state recognition, the Piscataway had to provide documented proof that the tribe was both native to Maryland before 1790 and in the state continuously since then. Neither Piscataway group has federal status.

Subsequently, the Accohannock Indian Tribe of the Eastern Shore was granted state recognition in 2017. Other active, indigenous Maryland tribal groups without state recognition include the Assateague Peoples Tribe, the Nause-Waiwash Band of Indians, the Pocomoke Indian Nation, and the Youghiogheny River Band of Shawnee Indians. (The Lumbee tribe, a significant number of whom emigrated from North Carolina to the Baltimore area in the 20th century, have not sought Maryland recognition.)

GABRIELLE TAYAC, GRANDDAUGHTER OF TURKEY TAYAC, AT PISCATAWAY NATIONAL PARK IN SOUTHERN MARYLAND. SHE SERVED AS THE INAUGURAL CURATOR, HISTORIAN, AND EDUCATOR AT THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN.

efore Gabrielle Tayac, who earned her PhD in sociology from Harvard University, accepted a position in the history department at George Mason, she served as an inaugural curator, historian, and educator at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. One of the exhibitions that she curated at the Washington, D.C., museum, which opened in 2004, is the permanent exhibition around the Native peoples of the Chesapeake Bay region. Several traditional items handmade by her cousin, Mark Tayac, including a feathered fan and beaver-skin pouch, are in the museum’s collection.

“I had the experience of knowing my grandfather. I was 11 when he died and 12 when he was buried and understood that people were against it and it took act of Congress,” she says, by way of explaining her own lifelong pursuit of local Indigenous history as well as her advocacy on behalf of Native tribes and their rights. “Those things had a very deep, profound effect on me. I also learned about the racism that my father experienced growing up here, before it was ‘cool’ to be an Indian, and just the devastating impact of those things in his life.”

Her father and her now-deceased uncle, Billy Redwing Tayac, who assumed leadership of the Piscataway Indian Nation after Turkey Tayac passed, both grew up in Southern Maryland. Her father, however, left and joined the Merchant Marines to escape the segregation and bigotry that he’d experienced as a schoolboy and teenager.

Now 58, Gabrielle was raised in the 1970s in Greenwich Village by her father and her Jewish mother, who were active in the artistic and intellectual pursuits of the era. Bookish by nature and aware of the injustices faced by Native Americans from an early age, she says, “I've wanted to know what had happened to us, why it happened, and to work for our rights for as long as I can remember.”

In particular, Tayac recalls a painful childhood visit with her father and grandfather to what was referred to as “the block house.” The block house was a structure that had been built atop of the sacred Piscataway burial site at Moyaone by the white, then-owners of the property—where school children and visitors were invited to view the ossuaries and remains of her ancestors as though it were a tourist attraction. The building came down in 1976 at the request of Piscataway leaders.

“It still flashes through my mind on occasion,” she says. “I was probably four years old, and it was a cold day. I think we had come [to Maryland] to visit the family for Thanksgiving, which is ironic. There were metal bars and these cinder blocks and so it looked like a prison. My dad picked me up to look in and I put my hands on the cold metal. I just remember vividly, viscerally, how scary it was because it’s scary to see skeletons? And not understanding what it was, it made me want to leave right away.”

That experience, and later others, including the long fight to get her grandfather buried there, stood in stark contrast to her own upbringing in New York City, which she describes as taking place in a “kind of an enriched bohemian environment.”

“It was such a disjuncture, I realized later. Why were we, why are we, being treated like this?”

A PHOTO FROM THE OPENING OF PISCATAWAY NATIONAL PARK, LOCATED IN PRINCE GEORGE'S AND CHARLES COUNTIES. TURKEY TAYAC STANDS SECOND FROM THE LEFT. —COURTESY OF WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

f Turkey Tayac were alive today, he most likely would be amazed by the re-emergence of American Indian culture and the renewed exploration of Piscataway history in Southern Maryland that he almost single-handed set in motion.

This past September, St. Mary’s County Historical Society hosted its now annual Indigenous Heritage Day. The well-attended celebration of Native American life past and present included demonstrations of traditional skills such as hide tanning, pottery making, cooking, and canoe making—plus an opportunity to walk through a replica longhouse.

The highlight was a colorful performance by Mark Tayac and the Piscataway Singers & Dancers, which brought members of the audience into its circle for their last dances. During Native American Heritage Month in November, the troupe is particularly busy, with performances at colleges, libraries, and arts centers, including an upcoming performance at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, which sold out last year.

Similarly, for the past 17 years, Prince George’s County has hosted an American Indian Festival at Patuxent River Park, featuring Native food vendors, traditional and contemporary Native American dances, demonstrations of Indigenous tools and technology, and a genealogical exhibit. This past summer’s annual Whispering Winds Pow Wow at the Howard County Fairgrounds included Indigenous artists and artisans, and drum and dance performances by members of Cherokee, Haliwa-Saponi, Iroquois, Lumbee, Navajo, Rappahannock, and Piscataway peoples. The Piscataway Conoy tribe’s annual Feast on the Waters and Green Corn Festivals are held on private property and therefore invitation-only, but last year they also organized an Indigenous People’s Festival at the Charles County Fairgrounds.

The most interesting development since Turkey Tayac’s battles over Indigenous land, rights, and artifacts might be the cooperation between Maryland archaeologists and Piscataway leaders.

Currently, teams of archaeologists and researchers from St. Mary’s College of Maryland, Towson University, the University of Maryland, and a variety of state institutions are working to uncover the history of Indigenous peoples in Southern Maryland. Of special note is the area around Chapel Point State Park, where Father Andrew White established his mission. Locating the parish could reveal the relationship between the first colonists and Piscataway.

“When we look at archaeologists, all the way through the 1970s, they were grave robbers and cultural robbers,” says Gray, the Piscataway Conoy tribal chair, adding that the tribe is still in the process of trying to identify and repatriate remains and artifacts warehoused decades ago by the Smithsonian and Maryland Historical Trust. “They were desecrating sacred spaces and the remains of real human beings and the content of their lives in the name of writing an academic report. Today, however, there’s a new set of archaeologists out here that listens. And I’m very grateful that they’re listening.”

Gray noted through their partnership, they’ve been able to identify Native American community locations with the unearthing of discarded oyster shell middens, arrowheads, ceramics, and stone tools.

Gray, who as a young activist participated in the Trail of Self-Determination and Longest Walk protest marches in D.C. in the 1970s, hopes Piscataway history can be more accurately portrayed and shared through signage in state parks and education about Indigenous peoples.

The Piscataway Conoy have also aligned with the Potomac Riverkeeper Network on environmental issues—a concern for Indigenous tribes—bringing a Mattawoman Creek sewage spill to public attention, for example, and working, successfully, to stop the Atlantic Coast Pipeline project.

There are other pressing concerns for the Piscataway as well. In his State of the Nation address to the Piscataway Indian Nation in 2023, Chief Mark Tayac highlighted what he often refers to as his “four talking points,” when discussing his and his tribe’s aspirations.

The first, is that they wish for all Marylanders, indeed all Americans, to know they are still seeking repatriation of all their ancestral remains. “So that they can rest in peace and that their bones and memories may return back to the womb of our mother Earth,” he says.

Secondly, highlighting Maryland’s relative prosperity and that the Piscataway are a historically land-based and agriculture people, he would like available public lands to be returned to their Indigenous owners. Thirdly, Tayac also believes the state has an obligation to build community centers for Indigenous people—in the way that the various ethnic and religious groups that settled on their land have community centers.

And finally, he wants the state to provide those centers with technical assistance and job training for “the next generation of Piscataway still to be born,” so that they can prosper and once again serve as able stewards of their lands.

“It has not been an easy journey for our people,” Tayac says. “With the swipe of a pen in the 1600s and 1700s, there were government officials [in Maryland] that said we have solved the Indian problem—there are no more Indians. But we didn’t all die then, and neither did the Indian spirit die in some John Wayne movie, like many people think.”

A NATIVE

AMERICAN PERFORMER

WITH THE PISCATAWAY

NATION SINGERS &

DANCERS AT A

SEPTEMBER EVENT.

half-century ago, Turkey Tayac had implored his family to continue pursuing his burial at the ancient site at Maoynne Reserve should he die before federal permission came to pass. Tradition held that alongside the grave of a Piscataway chief a red cedar tree be planted, which, according to their spiritual beliefs, serves as a channel from the ancestral relics to the living to the Creator.

That thriving red cedar tree, as well as a portrait photograph of Turkey Tayac surrounded by gifts and tokens, marks his well-maintained resting place all year round. Since the 18th century, Piscataway have buried their deceased in cemeteries the same as many Marylanders.

The late Chief Tayac, his granddaughter says, hoped to connect a new generation of Piscataway to their ancestors at rest at Moyaone. “Bury me there,” he had told his family and people, “and I can help you forever.”

For decades after his death, his family, their loved ones, and other Piscataway and Indigenous people made a ceremonial march to that Tree of Life at Moyaone. Accompanied by drum and song, they carried small bundles of tobacco, which represented the loved ones they wished to recall, walking a path of prayer and reconciliation. They stopped four times along the way, one for each direction, reflecting on their loss with love, not sadness.

When the procession reached the Tree of Life, as the sanctified red cedar tree is known, they formed a half-circle on its east side. The west side of the circle, which would extend toward the Potomac River, was left open for the spirits of their ancestors.

“The Piscataway buried their dead together in ossuaries during the Feast of the Dead ceremonies for centuries,” Gabrielle Tayac explained in a personal essay several years ago. “And it remains a very important day for us,” she says. “People collective in life, they would be a people collective in the Spirit World. For a while, we as Piscataway people are back in our ancient home, with our ancestors, and with the living. That is how we come full circle.”