History & Politics

Bootleg Bunch

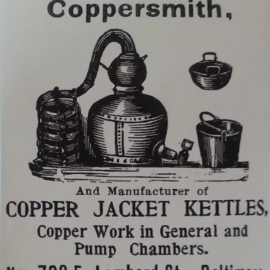

During Prohibition, the still-going Joseph Kavanagh Company turned from coppersmithing to bootlegging.

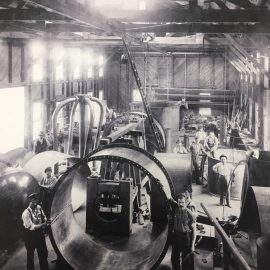

Inside the sprawling metal shop that bears the family name, Joe Kavanagh watches as nephews Paul and Patrick Kavanagh huddle after hoisting a 12-foot steel beam—assisted by an overhead lift—onto an 18,000-pound, medieval wheel-like device for bending. (When you see buildings with cool curved walls or arches, this is the place where their support architecture takes its final shape.) “Sometimes you’ve got to let them figure it out for themselves,” says Joe, glancing over his shoulder.

The younger Kavanaghs, 31 and 28, respectively, represent the sixth generation to work in the business, a century-and-a-half-old institution struggling to stay afloat as President Trump’s tariffs wreak havoc on the cost of steel and aluminum. It’s not the first time national politics have threatened the company’s bottom line. Their ancestors made their first real money building and servicing distilleries in hard-drinking, post-Civil War Baltimore.

In fact, the original Joe Kavanagh—great-great-grandfather of the 54-year-old Joe now in charge—socked away enough dough to rebuild after his first plant, and much of the city, burned to the ground in 1904. (The name—Joseph Kavanagh Co. Practical Coppersmith—remains legible in huge, if weathered, block lettering at the former Pratt Street and Central Avenue location where they plied their trade for more than eight decades before moving to Dundalk.)

But the Great Baltimore Fire proved a minor setback compared to Prohibition—which was ratified 100 years ago this month. Half of their business was in distilleries.

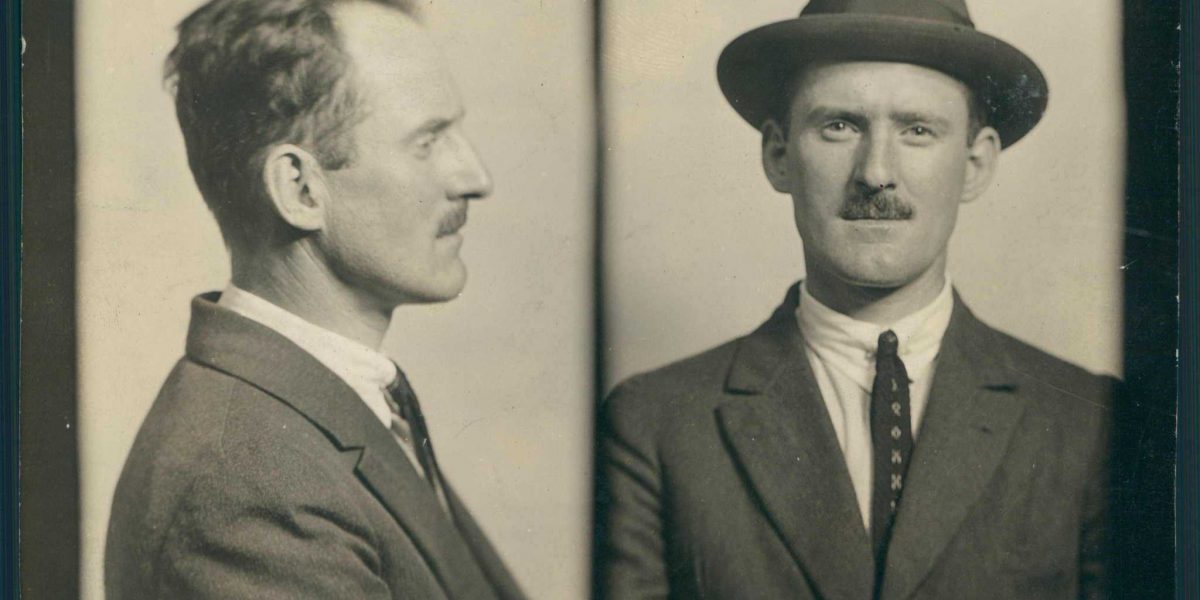

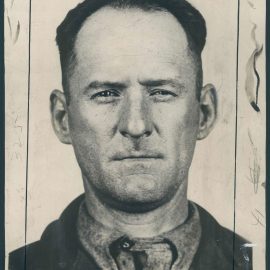

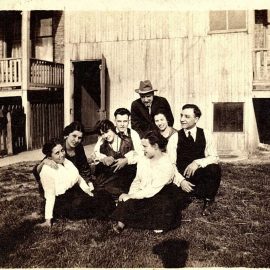

Enter Jimmy Connolly, aka “Jack Hart,” who had married into the family a year earlier, wedding Kitty Kavanagh following his release from Sing Sing. Hart let it be known to Kitty’s male cousins, then running the operation, that he had connections if they wanted, or needed, to stay in the booze biz. And so, the Catholic, previously upstanding Kavanaghs became bootleggers—with Jack and Kitty eventually earning infamy as Baltimore’s Bonnie and Clyde. It’s all documented in taped family oral histories and news accounts, which the current Joe has spent years poring over.

“We’ve had our share of ‘colorful’ characters,” acknowledges Joe Kavanagh. “Kitty’s father shot a Baltimore bartender in the neck.” The Kavanaghs have seen tragedy, too. One ancestor quit and took off to Panama to work on the canal after his son and wife died. He succumbed to malaria in the Canal Zone.

Not content with mere bootlegging, Hart later became the subject of one of the biggest manhunts in the city’s history in the summer of 1922 after he and an accomplice robbed $7,263 in payroll from a local company, shooting and killing the company’s treasurer in the process. Apprehended at a Washington, D.C., hideout a month later, Hart attempted a half-dozen prison escapes, succeeding twice—first in 1924 by bending a pair of metal bars with an iron rod and then again in 1929 after cutting his way through three locks of his solitary confinement cell. “Using tools of his trade, not ours,” Kavanagh notes. The FBI kept Kitty under constant surveillance each time Hart went on the lam, but she never never tipped off police to his whereabouts. According to press accounts, she fainted once after being informed her husband had been captured.

Meanwhile, the rest of Kavanaghs kept making clandestine distilleries, secretly shipping them out to clients, likely via the Baltimore harbor, while also mixing their own rye whiskey.

Through Prohibition, the Depression, two World Wars, and too many recessions and crises to remember, the Kavanagh clan—more than two-dozen have worked here in the company’s history—kept at their legal work as well. They have contributed railings and fittings to everything from the Statue of Liberty to Oriole Park.

“I don’t want to lose this business. Not on my watch,” he continues. “I started working on Saturdays with Dad when I was 12. You know, I studied classical guitar for two years at Peabody. Everyone in the family is a musician. Patrick plays clarinet. Paul plays the trumpet and tuba. My uncle played the piano, and my dad sang. Nobody asked me to quit college and come full-time. This place just gets under your skin, and there wasn’t any reason to put it off any longer.

“This place was my destiny.”