Home & Living

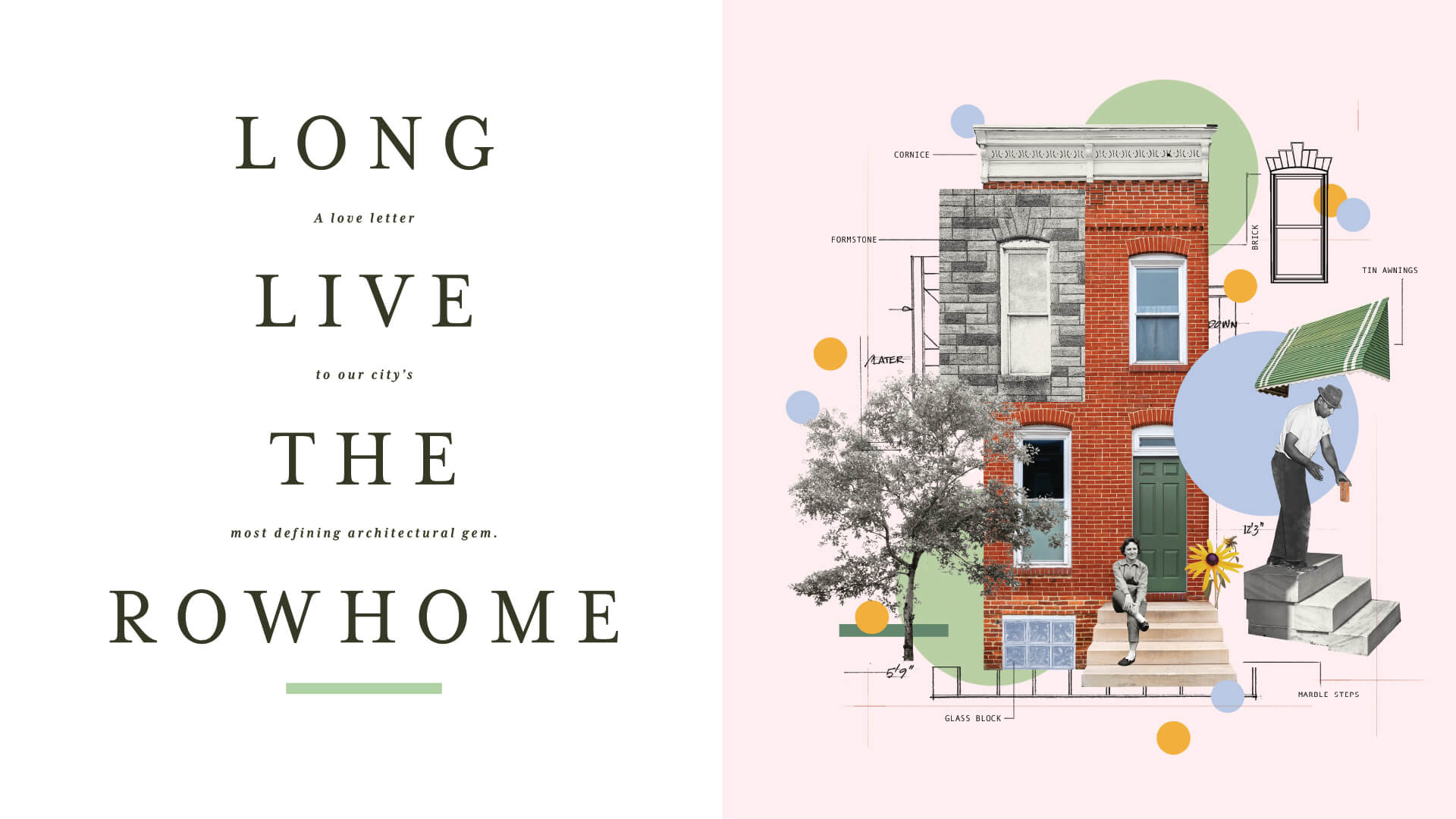

THERE ARE A FEW MOMENTS when you really see it. You come over a hill on O’Donnell Street on the eastern edge of the city. You pass down a stretch of Pratt from the far west side of town. Perhaps you’re heading south, along St. Paul. Or coming up north, from the bridge on Hanover. Often enough, you almost miss it, just an ordinary sight while getting to where you need to go. But other times, at just the right moment, it strikes you—something like awe. Out ahead, Baltimore unfurls across its undulating corridors. And for block after block after block, mile after mile, all the way to the horizon or heart of downtown, it’s nothing but one thing: rowhomes.

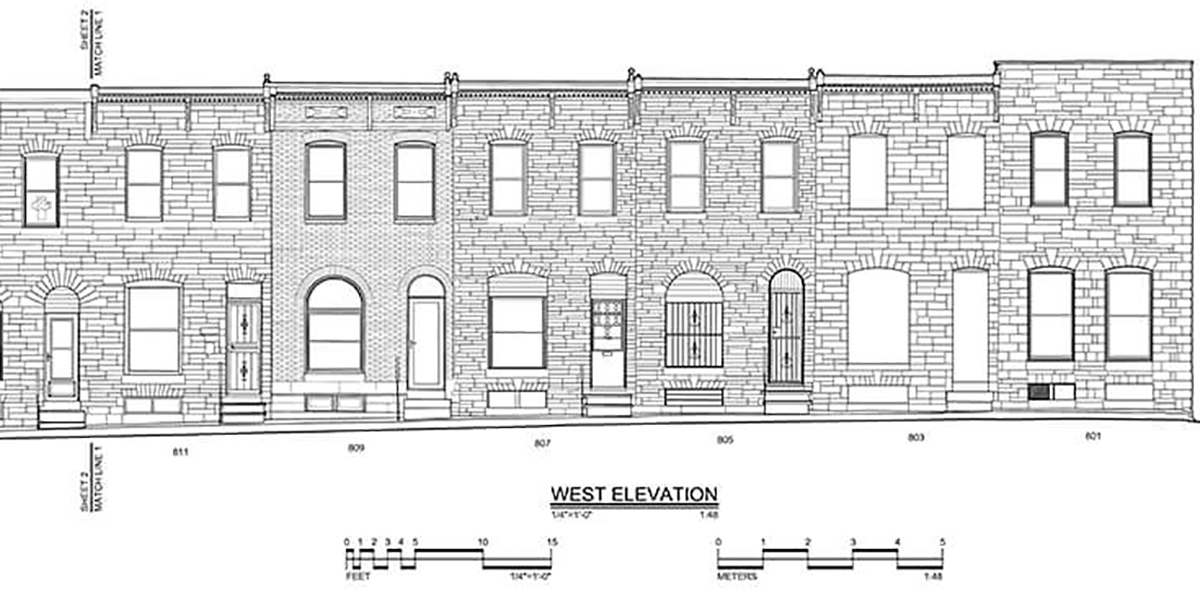

Survey drawings of North

Collington Avenue in Eager Park. —LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

“The rowhouse is the basic building block of Baltimore,” says Eric Holcomb, executive director at the city’s Commission for Historical and Architectural Preservation, aka CHAP. “It is the architectural form that ties all of this together . . . giving it its context and its character.”

Holcomb is pointing to a city map, hung on the wall of his office, located in a drab skyscraper across from City Hall. A carpenter turned career preservationist, his eyes light up when asked about rowhomes—the vernacular architecture that dominates the local housing stock, loosely defined as a series of residential structures that share side walls, often built in one fell swoop.

It’s not quite a duplex, or a townhome, or a condominium. Instead, the rowhouse turns out to be its own diverse, dynamic, egalitarian vessel, one that has emerged in nearly every neighborhood and evolved for more than two centuries alongside Baltimore, arguably becoming its most defining feature (despite at times being derided as monotonous and mundane).

In other words, it’s an underdog. And while other American cities have built them, too—Boston, Philadelphia, New York, D.C., on down to Richmond—where else do these rows remain so deeply entrenched in the local sense of identity?

In Baltimore, “the rowhouse has demonstrated that this very basic rectangular box can be made anew over and over and over again,” says Holcomb, his filing cabinet stuck with a fading “Stop the Road” sticker, from when a scrappy group of citizens saved swaths of them from I-95’s path in the early 1970s. “And that’s the exciting piece—it’s still evolving. While we’re not building block after block like we used to, new rowhouses are still being built, every day.”

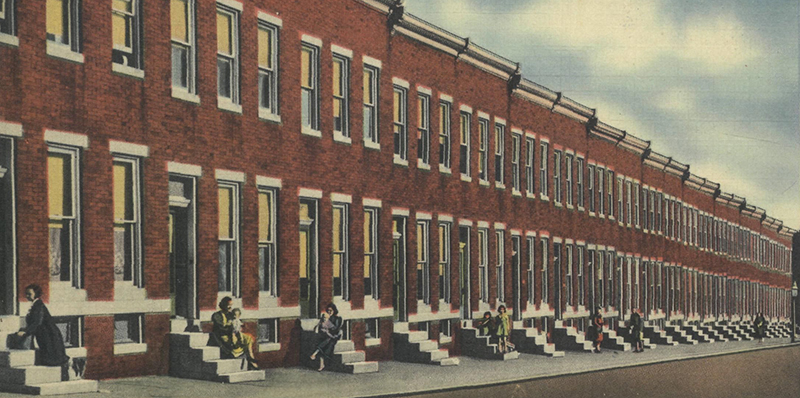

AN UNKNOWN STRETCH OF ROWHOMES WITH WOODEN STEPS, CIRCA 1938 —Courtesy of the Library of Congress

TODAY, IT’S SAFE to say that there are thousands upon thousands of rowhomes in Baltimore, with half of the city’s 251,000 occupied housing units categorized as attached single-family dwellings. No one knows who built the first one, but around the time we incorporated in 1796, they started to crop up around the harbor’s edge. “The very location of the various styles of rowhouses speaks directly to patterns of city growth,” rippling out in concentric circles, write scholars Mary Ellen Hayward and Charles Belfoure in The Baltimore Rowhouse.

A marble-stepped postcard. Courtesy of the Baltimore City Archives.

First, they arrived in Fells Point, then Federal Hill—often two stories high, two rooms deep, with a gabled roof and dormer windows, made of wood and brick in the classic Federal style then fashionable in England. An economy of scale, it was faster and more cost-effective to build several at once. And a “ground rent” system also made it beneficial for the buyer, who saved money by purchasing the home but only leasing the land.

Before long, demand exploded, thanks to our bustling port, an influx of immigrants, and the burgeoning B&O Railroad. “We were bursting at the seams,” says Johns Hopkins, executive director of Baltimore Heritage. “If you needed to build quickly, rowhouses were the answer.”

But not all rowhomes would be the same. By the 1850s, Baltimore was on the cusp of an industrial revolution, with its newfound prosperity reflected in the latest Italianate style, reserved for the city’s emerging middle and upper classes, as well as the manufacturing elite. From Mount Vernon and Bolton Hill to western squares—Union, Franklin, Harlem, Lafayette—the three-story style was bigger and more elaborately embellished with the likes of marble, cornices, and cast iron. In time, builders also constructed modest versions on side streets and alleys for the everyman, located near factories, breweries, and mills, from Locust Point and Pigtown to Hampden, Canton, and Brewers Hill.

“During the 19th century, rowhouses sheltered almost all Baltimoreans, from the very rich to the very poor,” and across racial and ethnic lines, too, write Hayward and Belfoure. Back then, “The two-story houses that were put up in my boyhood . . . all had a kind of unity, and many of them were far from unbeautiful,” recalled H.L. Mencken in The Baltimore Sun of his 1883 Hollins Street home, also describing them as “sometimes very charming” and “always dignified.”

Rowhouses, circa 1940s. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History & Culture.

But the real boom came at the turn of the 20th century. As steam-powered machinery further reduced material cost and increased production, large-scale developers started buying up acres of countryside and building en masse—no longer focusing on single rows but entire blocks and even neighborhoods, largely for the working-class. To lurein customers, each added their own distinct "touch of class.” Like Edward Gallagher, who installed stained-glass transoms around Patterson Park. Or Frank Novak, dubbed the “two-story king of East Baltimore,” who laid some of the first marble steps near McElderry Park.

From early on, we eschewed other dense housing like tenements and apartments as a source of pride, wrote George Howard in his 1873 The Monumental City. Even “the humblest mechanic or laborer can ensconce his family in a modest dwelling and surround them with the pleasures and comforts of home.” For many, these rows were the American Dream, with many an immigrant family living upstairs while opening a business on the first floor.

Soon, transportation further accelerated development. By the 1880s, Baltimore’s first streetcars drew more prosperous residents north to a variety of mansion-esque, Renaissance Revival-style rows: the dark, decorative Queen Annes, like Belvedere Terrace and Reservoir Hill; the rounded “swell fronts,” as in Mid-Town Belvedere or Edmondson; the white-clad “marble houses,” near Clifton or Carroll Park; the pastoral “porch fronts” around Charles Village and Montebello.

This period marked the start of suburban exodus, as residents of a certain means sought space, but also segregation, by both class and race. Despite early integration, hysteria ensued as Baltimore’s Black population doubled in the early days of the Great Migration. In 1910, the city enacted the nation’s first redlining law that banned Black residents from living in white neighborhoods, exiling them instead to overcrowded blocks to the east and west, where they still fostered their own thriving communities. Meanwhile, zoning commissions were enlisted to enforce city-county lines, spurning the rowhouse as a symbol of urban decline.

And yet it endured, fanning out even farther through the automobile age. Competing with the county suburbs, new “daylight” styles sprung up for white-collar workers on roads bound towards the city limits, these even-wider rowhomes adding front porches, lawns, rear garages, and a window for nearly every room. Near old Memorial Stadium, Ednor Gardens is a prime example, with floral and pastoral landscaping.

But the writing was on the wall. Cities had fallen out of fashion, and after World War II, houses were still being replicated— just now as cul-de-sac after cul-de-sac of single-family detached dwellings in the suburbs, a la Levittown. Then, in the name of urban renewal, bulldozers came for the city’s rows. But luckily, not long after, so did the first waves of preservationists, with dollar-house homesteaders igniting an ongoing praxis of restoring these historic homes. Ironically, Baltimore’s stalled growth over the last half-century might have played a part in saving them, too.

Rowhouses in Canton, circa 1905. Courtesy of the MCHC.

More recently, Mayor Brandon Scott has announced plans to tackle the city’s 13,000 vacant houses by investing $3 billion to restore entire blocks over the next 15 years. And there are a variety of city and state tax credits that also exist for buying or rehabbing rowhomes, as well as grants like Live Baltimore’s Buy Back the Block program. Last year, 6,500 attached houses were sold in Baltimore, compared to 1,200 detached, as new generations continue to discover them. Those numbers will soon include some of the buzziest construction projects, including Locke Landing in Baltimore Peninsula and Reservoir Square in Reservoir Hill, which, despite heralding themselves as townhouses, are clear descendants of humble rowhomes.

Residents hanging on their rowhome stoops. Courtesy of the BCA.

Still standing, these resilient rows continue to tell volumes about this city. From block to block, or neighborhood to neighborhood, styles evolved, and the structures adapted to changing times and needs. Even within a single home, there is a wellspring of stories—from the hardwood floors to the brick façades to the tin ceilings—each linking Baltimore’s past and future, as we explore below.

And altogether over time, from utilitarian dwelling to Baltimore icon, this local icon has become one of the city’s great unifiers, then and now housing every walk of Baltimorean. For better or worse, we share walls, and and without garage doors or driveways, we spill out onto our sidewalks, stoops, porches, and roofdecks together, turning neighborhoods into communities.

“It’s not so much the house itself than all the houses together, and the people in them,” says CHAP’s Holcomb, leaning back in his desk chair. “What’s that cliché? The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.”

OPENING COLLAGE: ROWHOME, STAIRS, & AWNING: CHRISTOPHER MYERS; MAN/BRICK: BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF INDUSTRY; RENDERING DETAIL: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. ALL OTHER PHOTOGRAPHY: SHUTTERSTOCK.

Brick

At the Foundation

AN ESSENTIAL ELEMENT EMERGED FROM THE GROUND UP.

hen Captain John Smith made his 1608 voyage up the Chesapeake Bay and into the Patapsco River, what stood out to the English explorer as the distinguishing characteristic of what would become Baltimore’s basin was its color: “a great red bank of clay.”

It seems Smith was looking south, to Federal Hill, which at the time was not the gently sloping grassy knoll we know today, but a series of steep and ragged bluffs, their rich raw earth exposed.

“You can imagine coming into the harbor, and amidst this heavily wooded landscape, there’s just this gigantic clay mound that pops up out of the water,” says David Gleason, president of the Society for Preservation of Federal Hill and Fells Point. “It would have certainly made an impact.”

And so it did. A century later, as industry emerged along those very shorelines, an elaborate network of tunnels was carved beneath that hillside, initially to excavate its prized clay for making pottery—but also brick.

Today, as in the times of Smith, the color red remains one of the most apparent attributes of Baltimore, thanks to our ubiquitous brick-built rowhomes, each a byproduct of the local landscape. On the cusp of the Piedmont Plateau and Atlantic Coastal Plain, we sit atop a plentitude of prehistoric clay deposits, which were mined, molded, and fired into the literal building block of this city as it endures today.

“The growth, the shapes, and even the color of Baltimore have been greatly affected, from earliest days, by the fortuitous presence underfoot of an abundance of rich, gooey clay,” wrote The Sun in 1952.

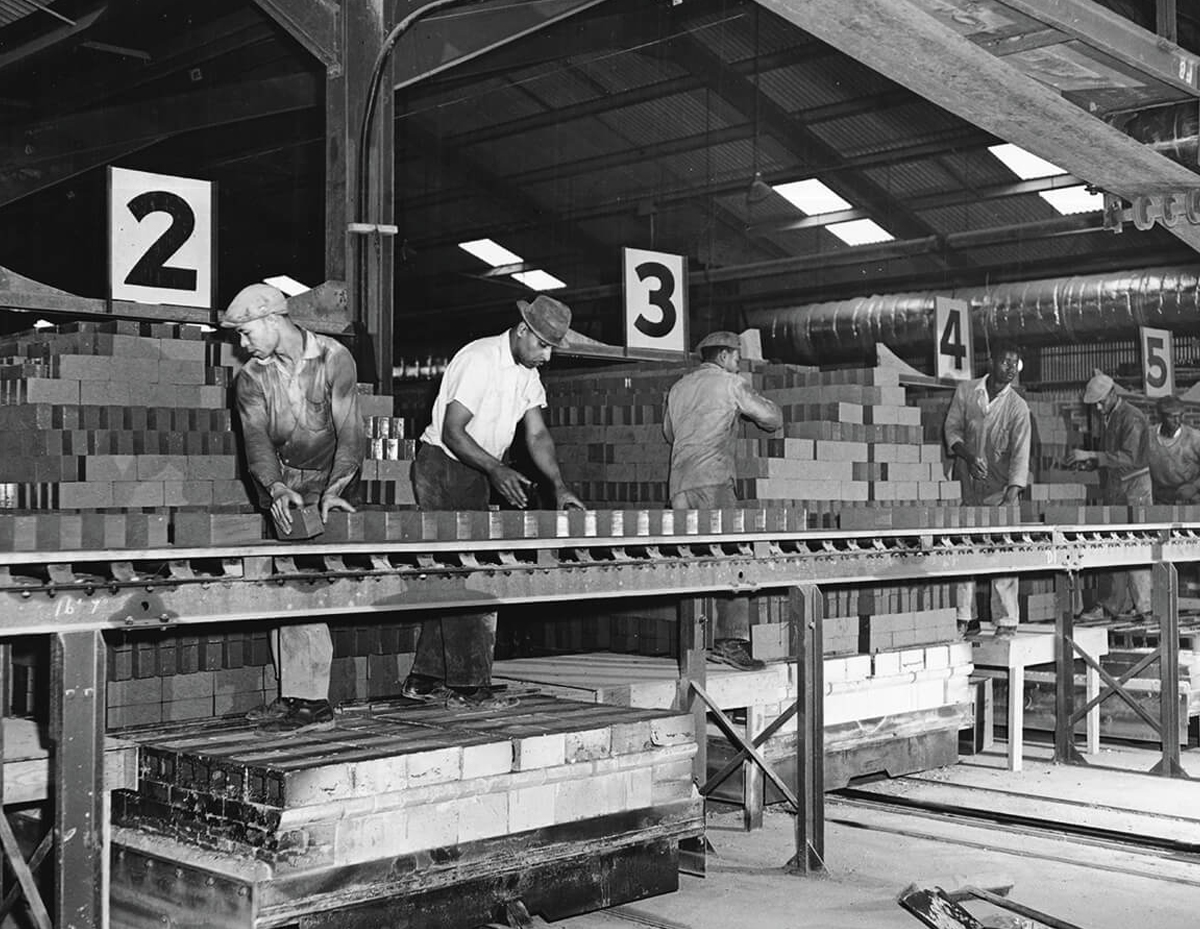

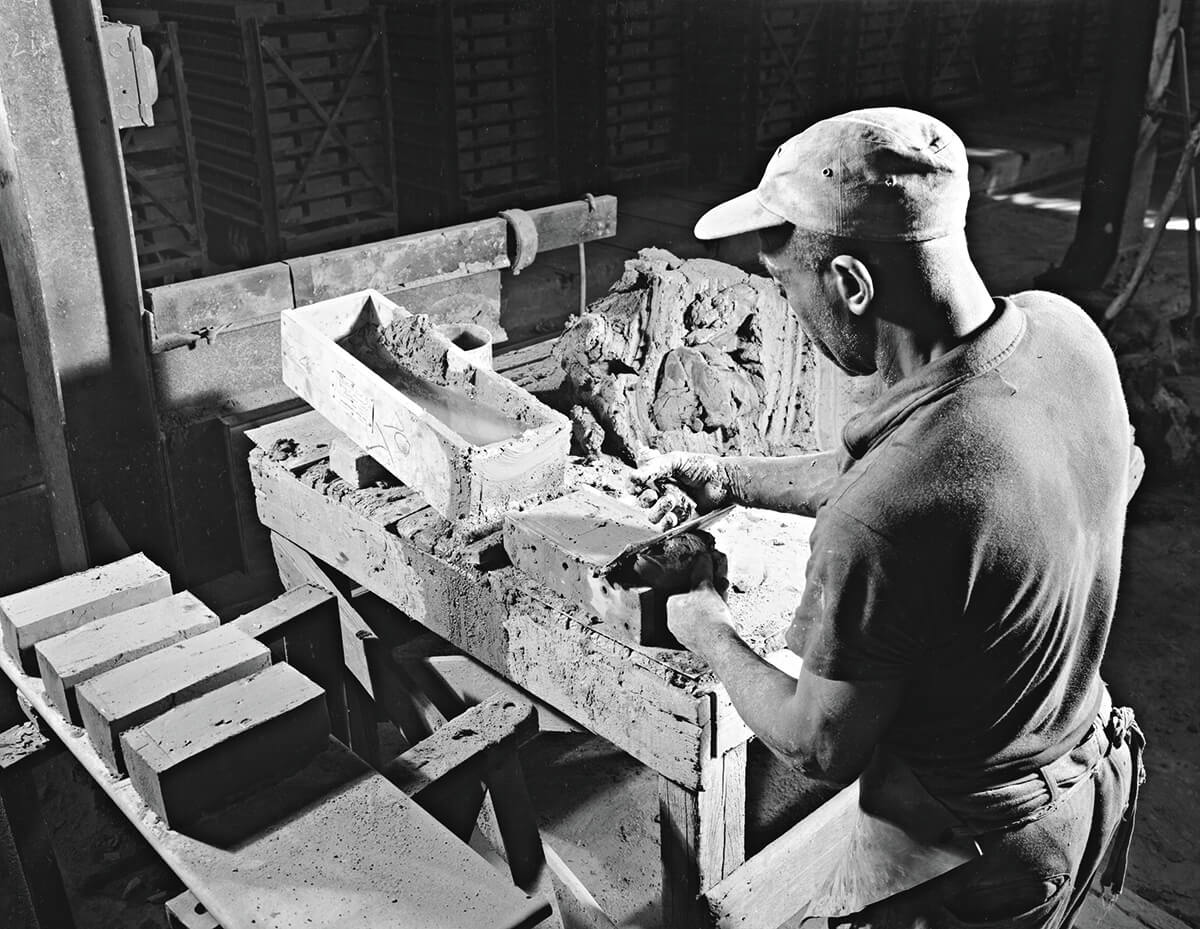

The city’s rich brick making industry. Courtesy of Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Lore has it that our first bricks arrived via England as the ballast of ships, but local clay was used for brickmaking in Baltimore as early as the 1700s. And when, at the turn of the 19th century, city ordinance outlawed wood-frame construction for fire prevention, it ignited a boom for brick—more durable than lumber and abundant than stone—and in turn helped meet the home-building demand of our rapidly growing city.

Of course, many major American cities built with brick, but the material “really becomes synonymous with Baltimore,” says Gleason. “This was a great epicenter of brick manufacturing, and from early on, you can see the high degree of skill that went into making it here.”

The earliest brickyards were south and west of the Inner Harbor, including one under M&T Bank Stadium and another at Mount Clare. At first, the bricks were made by hand, with both enslaved and hired workers cranking them out with astonishing speed. Their wares were used for home-building within the vicinity, but with the advent of railroads, were eventually shipped out across the country, gaining an international reputation.

The machine age only increased quality and quantity, with some 30 million made a year leading up to the Civil War. By the turn of the 20th century, most operations merged into the massive Baltimore Brick Company, located on 1,200 acres near Orangeville, where steam-powered shovels and later gas-fired kilns churned plumes of smoke into the air.

But a brick is more than just a brick in Baltimore. Walk the city and you’ll come across a whole variety—sometimes in a single home. There are the handmade versions of earlier eras, still found in harbor-front neighborhoods. Or the smooth pressed “face” brick of the 19th century, which became the go-to for façades. Rough “common” brick was structural, and what’s often revealed in exposed walls now.

Also of note are the various bonds of brick, aka patterns in which they’re laid by masons, from the old-school “Flemish” to the more contemporary “running”—first into oyster-shell mortar, then later Portland cement. Not to mention the brick embellishments, from doorways to windows to cornices (see Belvedere Terrace in Greenmount West).

Eventually, times changed, and the brickyards closed—their prodigious clay pits filled in, then built over with new neighborhoods, at times with row after row made from that very same brick, those colorful façades standing the test of time. “It’s a beautiful orange-ish red,” says Gleason, “and when the sun hits it, it can be really striking.”

Lumber

THE CHARM OF ANCIENT TREES

When Max Pollack of Almanac Hardwood gets a stack of lumber salvaged from Baltimore rowhomes, he knows one thing for sure: It’s going to be yellow pine. In the city’s early days, we built our houses with logs from local groves of white pine. By the turn of the 20th century, though, they’d been all but Lorax-ed, and so we moved on to the massive yellow pine forests of the Deep South.

A dense, durable wood, it was shipped up the Chesapeake by schooner, milled in the many lumberyards of what is now Harbor East, then used in every inch of building, from flooring and joists to studs. At the time, these slow-growing trees were upwards of 150 feet tall, four feet wide, and five centuries old, yielding ring-rich grains full of resin, making them especially colorful and fragrant.

“Nothing we buy today compares,” says Pollack, noting that the yellow pines, too, were eventually clear-cut, replaced by the younger Douglas fir and hemlock of the Pacific Northwest. “It is truly one of the most beautiful woods there is.”

BELOW: Illustration by IStock/Mateusz Atroszko.

In 1892, one-time Fells Point ship caulker Frederick Douglass built five brick rowhouses on the 500 block of South Dallas Street as rental properties for Black residents, which still stand today.

Marble

A Vision In White

OUR HISTORIC STOOPS ENDURE AS A BEACON OF CIVIC PRIDE.

erhaps the most prolific image of Baltimore is a black-and-white, circa-1946 photograph taken by The Sun’s A. Aubrey Bodine. In Wash Day, men, women, and children assemble along Penrose Avenue near Franklin Square. Armed with brushes and buckets, crouched on hand and knee, a sea of suds running behind them down the street, they are taking part in a ritual performed for more than a century in this city—the cleaning of the marble steps.

“In any block, there is seldom a day that someone is not out scrubbing them,” wrote Bodine. “On the older houses, the scraping of countless thousands of footsteps has worn grooves in the stone.”

Stairs, steps, stoops—these white-stone entranceways have become as much a symbol of this city’s local pride as Orioles baseball or National Bohemian, and arguably the rowhome’s most beloved detail. Thousands of them stand guard from north to south, over east and west, in nearly every city neighborhood.

It all began in the early 1800s, when a vast vein of white stone was discovered underground in Cockeysville. Before long, the Beaver Dam quarry would become one of the major sources of marble in the United States, ushering in our “Monument City” era—the material helping to make Mount Vernon’s Washington Monument, as well as Washington, D.C.’s. (Not to mention City Hall, the Enoch Pratt, the Peabody, and even the nation’s Capitol.)

The Beaver Dam quarry, circa 1910. Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History & Culture.

By the turn of the 20th century, as Baltimore reached an industrial heyday and experienced a related housing boom, hundreds of laborers were mining the quarry for its marble—first by hand, then using steam-powered machinery—with thousands of tons hauled out each day, hoisted onto ox-pulled wagons, then heaved down the railroads to the dozens of marble purveyors in city limits.

Hilgartner Natural Stone Company was one such enterprise. Founded in 1863 by German immigrants, its 30-horsepower saws cut this county marble into everything from the headstones of Greenmount Cemetery to the halls of The Walters Art Museum to its most iconic product—those residential marble steps.

Now the country’s oldest continuously operating stone company, with a shop still open in Westport, it’s said to have once been the largest in the nation, with branches in Chicago and Los Angeles, as well as an import outpost in Carrera, Italy (no big deal—just the source of marble for Michelangelo’s David). And today, their very own sculptor, Sebastian Martorana, transforms old Cockeysville marble into modern works of art. The stone behind his sculpture acquired by the Smithsonian in 2012, for instance?

“I pulled it out of woods of Druid Hill Park a decade ago,” says Martorana, an independent contractor for Hilgartner, who, in addition to his art, works as a carver and restorationist. “A beautiful piece of stone. It had been thrown away.”

This was not an uncommon score for Martorana. From early on, salvaged marble steps (and lintels and ledges) have been the material of choice for this MICA grad and now Barclay resident, who has rescued them from redevelopment, demolition, and illegal dumping sites throughout the city. The allure lies not only in this being a free and attractive medium, known for its dazzling color and diverse veins, but also that it’s a disappearing resource.

“Once it’s gone,” says Martorana, “you can’t replace it.”

That's because, after the Great Depression, Cockeysville marble was steadily replaced by cheaper concrete. The last stone came out of Beaver Dam in 1934, and within two years, the 200-foot gullies were flooded with natural spring water. Now, the Beaver Dam Swimming Club offers Baltimoreans a local swimming hole each summer.

But Martorana and his colleagues still repair plenty of marble steps. Inevitably, some chip, stain, or come apart from their mortar. His tips for care? Stop drilling railings into them. And follow the Bodine method: soap and water. Maybe even a little Ajax or Borox, too. Heck, he’s even used a pressure-washer.

“I live in a rowhome in Baltimore City, and marble steps are how we meet our neighbors,” says Martorana. “I’ve lived next to some for over 15 years, and I’ve barely been inside their houses. But we see them outside—we stoop. Which we know is a verb. These stairs are basically outdoor furniture. And believe it or not, they’re comfortable. Ours face west, and after a sunny day, they’re still warm in evening.”

Glass Block

Adding the industrial touch.

Famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright once called this the “super building material.” Invented for factories and now experiencing a retro resurgence, these jewel-like cubes have long provided Baltimoreans with privacy, security, and the plus of natural light.

The 2600 block of Wilkens Avenue is home to the longest stretch of rowhouses, with 52 circa-1912 homes known as the “Deck of Cards,” near Carroll Park.

Painted Screens

A CANVAS FOR COMMUNITY ART

Back in the day, during spring in East Baltimore, the city streets transformed into an outdoor art museum. First in “Little Bohemia,” the neighborhoods north of Patterson Park, and later in Highlandtown and Canton, you’d find front doors and windows filled with painted screens, a quintessentially Baltimore folk art said to have been started here by Czech immigrant William Oktavec in 1913.

Both functional and aesthetic, they let the breeze in but the gaze of neighbors out (as well as disease-carrying mosquitoes), while also beautifying blue-collar blocks with no yards and few trees. At one point, there were as many as 200,000 of them crafted by dozens of self-taught artists, says Elaine Eff, founder of the Painted Screen Society of Baltimore, each depicting colorful scenes of pastoral landscapes and, more recently, local landmarks, like Domino Sugar.

“They conveyed a sense of pride for their homes and city,” says Eff, who credits the advent of air-conditioning for their decline. But a handful of enthusiasts carry on the tradition, with workshops now offered at the likes of the Creative Alliance and Maryland Center for History & Culture, which is currently planning a permanent exhibition to showcase the painted screen.

Formstone

Rock of Ages

THE “POLYESTER OF BRICK” CHANGED THE FACE OF BALTIMORE.

hen you ask an architect or preservationist about the city’s second-most iconic façade, often they let out an audible groan. Love it or hate it, Formstone—aka “the polyester of brick,” as famed local filmmaker John Waters once put it—is undeniably intertwined with the fabric of Baltimore.

Patented here in 1937 by Pikesville resident Albert Knight, it wasn’t long before block after block of working-class neighborhoods got a facelift, with the stucco-like faux stone promising rowhome owners they’d never have to paint or point their brick again. From Shipley Hill to Little Italy to Highlandtown, this ersatz rock (and similar products started by competitors) was applied directly to building fronts throughout the mid-century, hand-sculpted into shape and sealed with a sparkling finish of spray-on mica, perhaps leftover from Beaver Dam marble.

“Made it look like Hollywood,” recalled one Highlandtown resident in the 1998 documentary Little Castles, with these newly decked-out digs symbolizing status and stability.

In total, thousands of rowhomes were covered in Formstone, which claimed to keep moisture out and heat in for a cheap price. But by the 1970s, the bloom was off the rose of this architectural wonder, which turned out, in fact, to be a maintenance nightmare, trapping moisture and causing the original brick to deteriorate. Complaints rolled in, sales dwindled, and in the decades that followed, large swaths of Formstone façades were removed, now dubbed by some as bad taste.

A half-century later, only a handful of repair and removal folks remain, but it’s easy to wonder: Is Formstone actually historic now? Should it be preserved? CHAP, for its part, takes a neutral stance.

“Eventually, it will come back in style,” says Waters in Little Castles, envisioning white-collar residents one day putting it back up, with a certain irony. “[They’ll] make it chic again when it’s finally all gone.”

The narrowest rowhome is 200 ½ East Montgomery Street in Federal Hill, measuring not even nine feet wide.

Stained Glass

HIDDEN TREASURES IN PLAIN SIGHT

On the 900 block of Luzerne Avenue, most of the addresses are etched into the transom above each door. There, a piece of early 1900s stained glass is framed in emerald green, with a complementary pane, featuring a rosy-pink diamond, built into the wide adjacent window. It’s an elegant touch for an otherwise ordinary stretch of East Baltimore, included on most of its neighboring rowhomes, and part of a tradition that pops up across many of the surrounding neighborhoods, and throughout the city.

At the turn of the 20th century, stained glass wasn’t just for churches—or the rich. Local builders incorporated it into a range of residences, from working-class to mansion, and in all shapes and sizes, including skylights. Some such adornments are small and simple, such as in Washington Hill and Broadway East, while others are large and ornate, like in Mount Vernon and Bolton Hill. The latter even includes some Tiffany examples, but most were forged by the city’s many glassworks.

By World War II, the colorful panes fell out of fashion, but a handful of artisans still carry on the craft today, at times decorating them with local details, like blue crabs or Black-eyed Susans.

For Linda Rabben, author of Through a Glass Darkly, which chronicles Baltimore’s stained-glass history, these works are a kaleidoscope of wonder, just waiting to be discovered. Walk around and keep an eye out, she suggests. “The more we look, the more we see.”

On a few last rowhomes from Highlandtown to Hampden and Waverly, ceramic Camark cats climb on exterior walls as a decorative midcentury novelty.

Stirling Street renovations, circa 1970s. Home materials at The Loading Dock in East Baltimore today. Courtesy of the MCHC and Christopher Myers, respectively.

Old Gems

Salvage warehouses save a piece of the past.

Robert Hooke was one of the first in line for Baltimore’s “dollar houses” in 1974. That year, he bought a pair of circa-1820 vacant rowhomes on the 600 block of Stirling Street, for a total of two bucks, and got to work right away on renovating them.

A Loch Raven native, Hooke had read about Mayor William Donald Schaefer’s affordable-housing, urban-renewal program in The Baltimore Sun. Not long after it got off the ground, requests from these new residents rolled into the city, asking if they could salvage the historic materials remaining in other vacants bound for the wrecking ball to use in their rehabs.

“Baltimore was knocking down entire blocks, making way for Route 40, which is how the Salvage Depot got started,” says Hooke, who, in 1975, was hired by CHAP to run the city’s own retail outlet for architectural scrap, the first of its kind in the country.

With a small crew, they culled the clawfoot bathtubs, mahogany doors, fireplace mantels, tin ceilings, metal cornices, entire staircases, and, of course, marble steps, which they sold back to the public for a song on Pratt Street. “We saved a lot—you name it, we had it,” says Hooke.

For two decades, the Salvage Depot preserved some of Baltimore’s finest but fast-disappearing details, most of which were no longer being made locally, and certainly not to the same standard. A laborious effort, it closed in the ’90s, but similar treasures can still be found at outfits like The Loading Dock, Second Chance, Housewerks, and Habitat for Humanity’s ReStore.

Now a mason himself— the reclaimed archway he added to his old Stirling Street rowhomes can be seen from the back alley today— Hooke continues to have a soft spot for the craftsmanship of the past.

“Everything now is done fast and cheap,” he says. “It’s harder to renovate than build new—nothing’s square, nothing’s plumb. But they don’t make them like they used to. It was a work of passion for me.”

Artist Loring Corning transformed the facades of two Parkwood Avenue rowhomes into fanciful glass mosaics in Reservoir Hill.

RESIDENCES OF NOTE

A rowhome retrospective of famous Baltimore residents.

ELIJAH CUMMINGS

2014 MADISON AVE., RESERVOIR HILL.

F. SCOTT FITZGERALD

1300 PARK AVENUE, MT. VERNON.

BILLIE HOLLIDAY

216 S. DURHAM ST., UPPER FELLS.

LILLIE CARROLL JACKSON

1320 EUTAW PL., UPTON.

THURGOOD MARSHALL

1623 DIVISION ST., UPTON.

H.L. MENCKEN

1524 HOLLINS ST., UNION SQUARE.

NANCY PELOSI

25 ALBEMARLE ST., LITTLE ITALY.

EDGAR ALLAN POE

203 N. AMITY ST., POPPLETON.

BABE RUTH

316 EMORY STREET, UNION SQUARE.

WILLIAM DONALD SCHAEFER

620 EDGEWOOD ST., EDGEWOOD.

GERTRUDE STEIN

215 E. BIDDLE ST., MID-TOWN BELVEDERE.

TUPAC SHAKUR

3955 GREENMOUNT AVE., PEN LUCY.

FRANK ZAPPA

2019 WHITTIER AVE., MONDAWMIN.

In harbor-front neighborhoods, those beloved roof decks were first added around Federal Hill in the 1990s.