Westinghouse engineer Stanley Lebar’s accomplishment—inventing a lightweight camera that could withstand the rigors of space travel—was no small feat at the time, and seems all the more remarkable in hindsight.

Developed for NASA’s 1969 Apollo 11 mission at a then-Westinghouse (now Northrop Grumman) plant in Linthicum, Lebar and his team’s seven-pound, black-and-white camera had to survive the velocity of liftoff, temperature swings from -250 to 300+ degrees Fahrenheit, and operate in the vacuum and difficult low light conditions of space. Back then, most TV cameras weighed 700 pounds. It’s their handiwork that enabled an estimated 500 million people around the world to watch 38-year-old Neil Armstrong’s “one small step man, one giant leap for mankind” walk on the moon in real time.

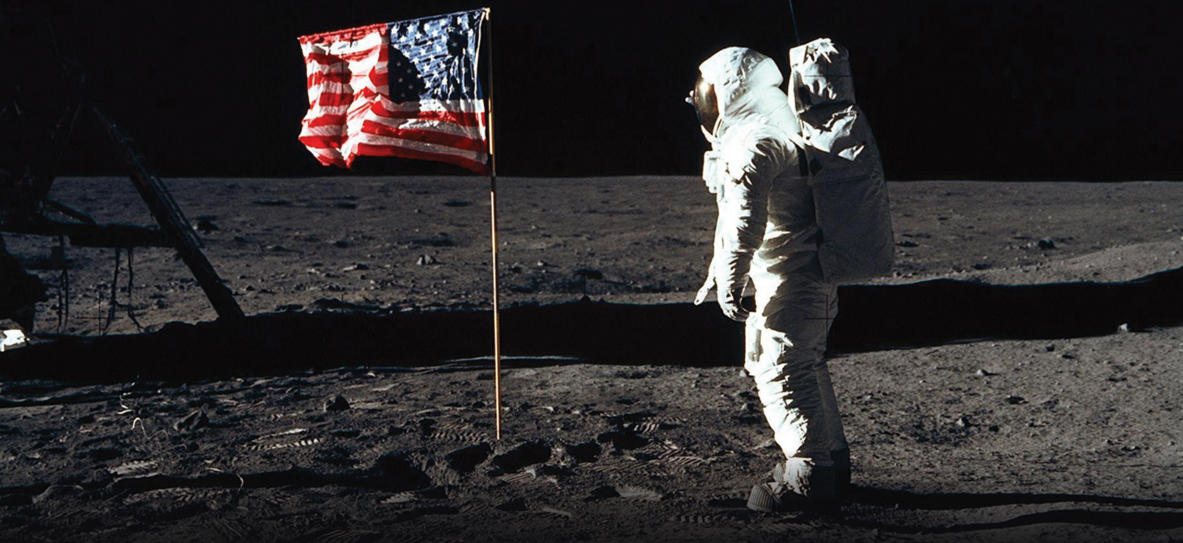

That was 10:56 p.m. Eastern time on the summer Sunday evening of July 20, 1969—50 years ago this Saturday. Shortly afterward, images of Armstrong, a civilian research pilot and commander of the mission, and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin planting the U.S. flag on the surface of the moon were also beamed home. After two-plus hours of walking and working on the moon, Armstrong and Aldrin rejoined astronaut Michael Collins in the lunar module.

Among the items left behind on the moon was a plaque that read: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot on the moon—July 1969 A.D.—We came in peace for all mankind.”

In October 1964, NASA had awarded Westinghouse the contract for the lunar TV camera. The camera that would go to the moon was first tested in space during the Apollo 9 mission in March of 1969. Lebar’s 75-engineer team’s color TV camera remained in the command module while the black-and-white camera was fastened to the outside of the lunar module.

Lebar passed away in 2009 at his home in Severna Park, but until the end he was excited about new technologies that were enhancing the initial grainy images that traveled 239,000 miles back from the moon. The legacy of Apollo 11, of course, wasn’t just the moon landing, but that the world gathered to watch it live together.

For the development of the lunar television camera and the color TV transmissions from the mission, Westinghouse received an Emmy award in 1970, which Lebar accepted.

Stanley Lebar, project manager for Westinghouse’s Apollo Television Cameras, shows the color camera on the left, and the monochrome lunar surface camera on the right. The color camera was used on all flights starting with Apollo 10, while the monochrome lunar surface camera was used on Apollo 11, and captured Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon.—NASA.

Stanley Lebar, project manager for Westinghouse’s Apollo Television Cameras, shows the color camera on the left, and the monochrome lunar surface camera on the right. The color camera was used on all flights starting with Apollo 10, while the monochrome lunar surface camera was used on Apollo 11, and captured Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the Moon.—NASA.

“Just imagine,” his son Scott Lebar, managing editor at the Sacramento Bee, recalled his father saying in an interview shortly before the 40th anniversary of the moon walk. “If you had video of the Pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock. Wouldn’t you want to see that? Wouldn’t you want that for everyone? That’s what this is, and we’re trying to preserve it for history and future generations.”

In honor of the anniversary, three videotape reels from NASA’s Apollo 11 mission described as “the only surviving first-generation recordings of the historic moon walk”—meaning unremastered—are scheduled to be auctioned at Sotheby’s in New York this Saturday.

That footage was among more than 1,000 reels that a former NASA intern purchased at a government surplus auction in the mid-1970s for $218. He didn’t know the contents of the tapes until 2006 when NASA admitted some original footage had been lost.