News & Community

Head in the Game

Brain diseases have shortened the lives of many of the city's beloved former Baltimore Colts. Can football survive CTE?

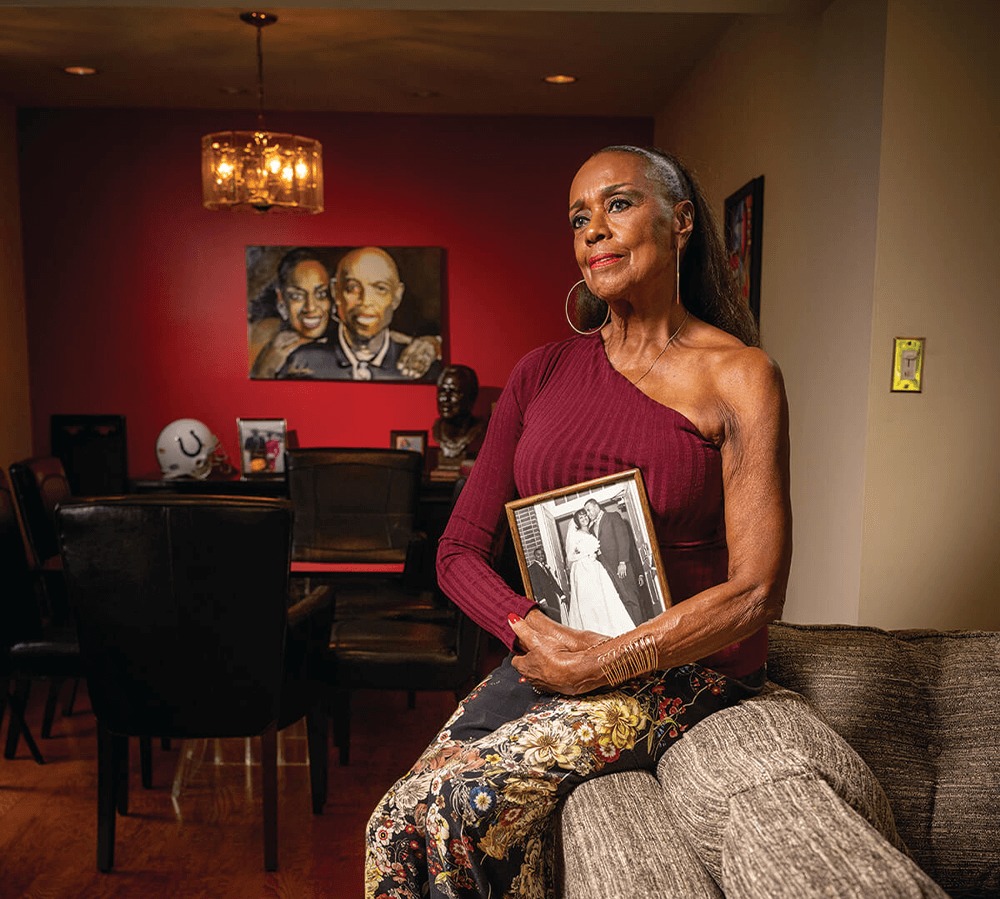

On the morning of September 11, 2001, at their home in Los Angeles, Sylvia Mackey and her husband, John, woke up to the news that terrorists had hijacked multiple American passenger jets, crashing two into the World Trade Center and a third into The Pentagon. Given the West Coast time difference, they spent those first hours in shock, watching the collapse of the twin towers over and over on television. Those horrific images, and that day, remain indelible for Sylvia Mackey 18 years later, though not exactly for the reason it does for the rest of the country. A flight attendant herself, she happened to have the day off and a dentist’s visit scheduled. Eventually, the couple pulled away from the TV and drove together to her appointment. Turning on the car radio, they listened to journalists continuing to report on the morning’s heinous attacks. John, however, suddenly had no recollection of the events they were talking about.

That was the moment Sylvia Mackey knew something was frighteningly wrong with her then 59-year-old husband, the legendary tight end for the Baltimore Colts whose 75-yard, second-quarter touchdown had made him one of the heroes of Super Bowl V. College sweethearts since their days at Syracuse University, they married six months after the Colts made John their No. 2 pick in the 1963 NFL draft. “Thirty minutes before, we’d been watching everything on television,” she recalls. “Now, he was asking questions and acting as if he’d just heard about it for the first time. ‘When did that happen? Did that happen today?’ How do you forget something like that so fast? I was alarmed, to say the least. In hindsight, I’d been in denial. There were signs with John going back for years.”

Over the next several months, Sylvia set up appointments with geriatric psychiatrists and neurologists. This was still four years before Dr. Bennet Omalu, a Nigerian-born forensic pathologist in the Allegheny County coroner’s office in Pittsburgh, would publish his breakthrough medical journal article on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)—a neuorodegenerative disease caused by repeated blows to the head. Omalu had discovered the disease during his autopsy of 50-year-old former Steeler Mike Webster, who had suffered from amnesia, dementia, depression, and erratic behavior. It was also 15 years before the NFL would publicly acknowledge a link between football and brain disorders.

Specialists at UCLA confirmed Sylvia Mackey’s worst fears. They diagnosed her husband with frontal temporal dementia, a relatively rare, progressive, and incurable brain disease. It affects one’s memory and ability to think, and in most cases causes significant changes in personality and behavior.

“The diagnosis was a relief, a blessing, but I also realized he wasn’t going to be a major financial contributor anymore,” Sylvia says. “I was going to have to do everything.” With her husband's hastening decline, one of the first decisions she made was to move back to Baltimore, where even a diminished John Mackey could earn some money signing autographs. More importantly, she realized, local fans would recognize her 6-foot-3, 225-pound husband if he got lost. Which he did, more than once, before passing in 2011. A few weeks after Sylvia purchased a condo for the couple in Cross Keys, following a Ravens game at M&T Bank Stadium, John got separated from her and their daughter, who later quit her job to become his caregiver. A fan returned him home. “John did know our address, and he’d made it back before we did,” she explains. “When I asked him how he got home, he didn’t even remember going to the game. He said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you all day. Where have you’ve been?’”

SYLVIA MACKEY CLUTCHES A wedding PHOTO OF her and JOHN IN HER home in cross keys.

John Mackey was not the first football player to suffer from dementia, obviously. The concept of CTE dates at least to the 1920s, when the colloquial term “punch-drunk” was already in use, referring to the group of symptoms that boxers more commonly displayed and which appeared to be the result of repeated non-lethal blows to the head. The formal name, derived from Latin roots, until recently remained dementia pugilistica. However, the potential for lasting harm to the brains of football players has also been long understood by the medical community and football organizations—even if commensurate protections for players were never implemented and the injuries remained something of a locker room secret. Whether that’s because the science wasn’t complete, or the money in college and pro football disincentivized efforts to take a critical look at the sport, remains an open question. As does how much the NFL knew and when they knew it. But the guidelines from as far back as the 1933 NCAA medical handbook, the 1937 American Football Coaches Association, and the 1952 New England Journal of Medicine all warned that concussions needed to be taken more seriously.

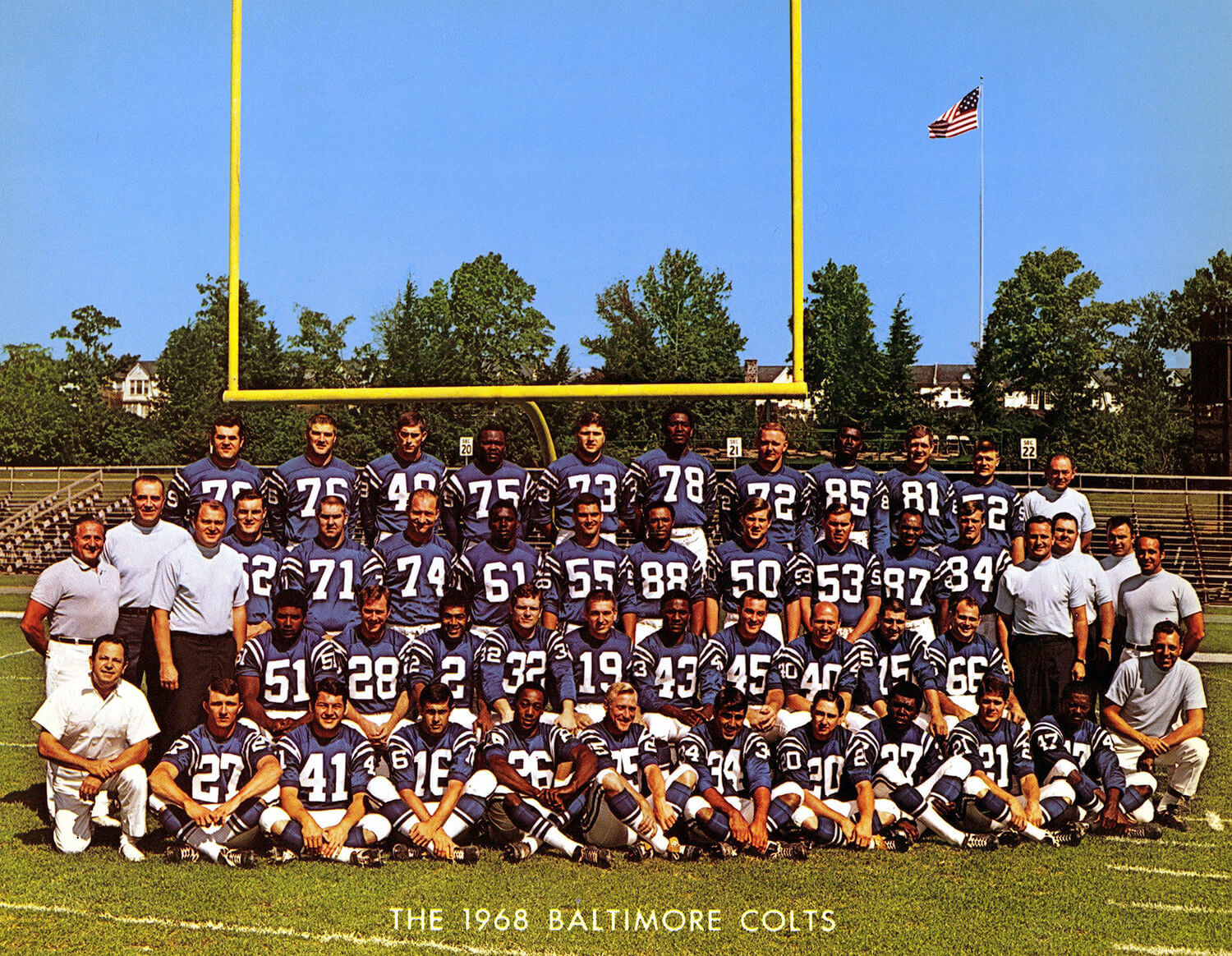

Team photo of the 1968 Baltimore Colts, who went 13-1 and won the NFL title that year before being upset by the New York Jets in Super Bowl III. At least 10 players and two coaches pictured experienced brain-related issues, likely related to football. AP Images

Today, the legacy of Baltimore’s beloved old Colts, stolen to Indianapolis by Bob Irsay 35 years ago, is the championships they brought the city in ’58, ’59, and ’70. But that legacy now also includes what CTE and brain diseases linked to repetitive head trauma—ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s—took from them. Even a casual survey of obituaries with references to brain-related issues reads like half of an all-time Baltimore Colts starting lineup: Mackey, Hall of Fame tackle Jim Parker (Parkinson’s), all-pro tackle George Preas (Parkinson’s), quarterback and 1968 NFL MVP Earl Morrall (Parkinson’s and CTE), running back and team co-captain Alex Hawkins (Alzheimer’s), all-pro wide receiver R.C. Owens (Alzheimer’s), all-pro center Forest Blue (CTE), all-pro guard Art Spinney (depression and headaches), guard Sisto Averno (Parkinson’s), all-pro guard Fuzzy Thurston (Alzheimer’s), all-pro running back Joe Perry (CTE), all-pro wide receiver Gail Codgill (dementia), all-pro middle linebacker Bill Pellington (Alzheimer’s), all-pro defensive end Bubba Smith (CTE), pro-bowl defensive end Ordell Braase (Alzheimer’s), defensive end Roy Hilton (Alzheimer’s), all-pro linebacker Don Shinnick (frontal lobe dementia), all-pro cornerback Bobby Boyd (dementia), all-pro defensive back and kicker Bert Rechichar (Alzheimer’s), defensive back Art DeCarlo (CTE), defensive back Jim Welch (CTE), cornerback Carl Taseff (progressive supranuclear palsy), linebacker Steve Stonebreaker (suicide).

There’s also former line coach John Sandusky and former defensive coordinator Chuck Noll (who left for the head job in Pittsburgh in 1969 and won four Super Bowls). Both had played professionally and suffered from Alzheimer’s.

“We were a family in that locker room,” says Bill Curry, the standout center on the great Colts teams from 1967-1972. “We loved each other the way brothers do. Not perfectly. We argued and we tussled. But we had each others' back. Every last one of us and we knew that. Now, I have survivor’s guilt, like you hear from guys who went into combat together. The guys who were in foxholes together and not everyone made it out safely.”

“I’m 76. I feel good and I am just lucky,” continues Curry, who went on to a successful head coaching career at Georgia Tech and Alabama. “A woman at an event recently told me ‘the Lord had blessed' me with my health. But I know there’s no God that would bless me and not bless Bobby Boyd and Don Shinnick.”

A Boston University study of brain tissue from 111 deceased former NFL players in 2017 found that 110 showed signs of CTE. Those figures are somewhat misleading, however. The samples in that study effectively came from a self-selecting group of donors—ex-players who displayed symptoms of disease prior to their death. Chris Nowinski, a former All-Ivy Harvard defensive tackle and co-founder of the Concussion Legacy Foundation, which works with BU, estimates the actual percentage of former NFL players with at least mild CTE is likely between 20 percent and 50 percent—still extraordinarily disconcerting figures. With more than 700 donated brains now in the BU CTE Center-associated brain bank, the latest research continues to support those results, Nowinski says.

“What you learn is that these are horrible diseases with no cure, and it’s a costly, long goodbye,” Sylvia Mackey says. “You also realize that you’re not taking care of the person you married and still love, you are taking care of the disease. The good thoughts of how you’re going spend your lives together disappear.”

Sections from a normal brain, left, and from the brain of former University of Texas football player Greg Ploetz, right, in stage IV of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). According to a 2017 report by the Journal of the American Medical Association, research on the brains of 202 former football players confirmed what many feared in life—evidence of CTE.Courtesy of Boston University

Given the prevalence of CTE now found in deceased ex-football players, there are, of course, also former Colts whose symptoms indicate they are living with the disease, which can only be confirmed for certain after death. Last year, I’d reached out to Tom Matte, who spent 12 hard-nosed years blocking and running over linebackers, for a story about the 50th anniversary of the Colts’ dramatic loss in Super Bowl III to Joe Namath and the New York Jets. When I told him that it was easier tracking down old baseball players than old football players, he agreed and sighed. I knew Tom a bit, we had collaborated back in 2006 on a football column called “Mondays with Matte” for the short-lived Baltimore Examiner. He told me he was now dealing with short-term memory loss and other cognitive issues himself, and seeing doctors at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. Over the phone, it wasn’t necessarily clear anything was wrong. He could recall all the details of the ’69 Super Bowl—both his 58-yard run and later fumble—but he did repeat a few anecdotes several times. In July, when I drove up to Matte’s home in Baltimore County near Loch Raven Reservoir to meet with him and his wife, Tom saw my pickup truck coming up the driveway and came out to greet me, outgoing and friendly as ever.

His wife, Judy, says she talks to Sylvia Mackey, who still lives in Cross Keys, regularly. “I bug her,” Judy says. “I have questions. A lot of it to be honest is financial stuff—how we will pay for more care when the time comes.” Both Judy and Tom Matte figure about half of the ex-Colts in their circle have faced, or are now facing, CTE or other brain injury-related diseases. They mention a couple of former Colts linebackers that they’ve heard are struggling, including Bill Laskey, a former Pro Bowler diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. They wonder how the former Colts they’ve lost touch with, or haven’t heard from in a while, are doing. Some, they believe, prefer to deal with the issue privately. “I know Bobby [Boyd] didn’t want anyone to know,” says Judy Matte. “I was in touch with Wendy [his wife] about Bobby and how he was doing and what they were going through. Diane Baughan has been taking care of Maxie [a former Baltimore Colt coach]. He’s not doing well. Another former teammate [who had concussions as a player] is having some problems. They’re all good friends. The guys who played for the Colts, so many of them stayed in the Baltimore area because they all had off-season jobs. They’ve been a part of our community and a part of the Baltimore community.”

“John and Sylvia were a great couple and great friends,” Tom adds. “Mackey and Matte. Our lockers were next to each other.”

There are less familiar players who have had issues, of course. Guys like former defensive back Dwight Harrison, who played for the Colts in 1970s and was diagnosed with dementia more than a decade ago. Backup quarterback Bill Troup suffered from memory loss, depression, and substance abuse before his death at 62 in 2013. It was only at the time of his passing that his adult daughters learned he’d joined a concussion lawsuit against the NFL. “We realized he must’ve known his problems were related to football. That’s when my sister and I decided to donate his brain and learned he had CTE.”

“Our parents got divorced after he retired,” says Laurin Garcia, one of Troup’s daughters. “I was in high school by then. My mother knew something was happening to him, but you also don’t know [what it is]. His symptoms ran the gamut. They just change. Unfortunately, Dad ended up by himself, isolated,” she says, choking up. “We couldn’t help him.”

Meanwhile, 59-year-old Art Schlichter, the Colts’ long-troubled No. 1 pick in 1982 draft, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and dementia eight years ago.

“When I asked him how he got home, he didn’t even remember going to the game. He said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you all day. Where have you been?’”

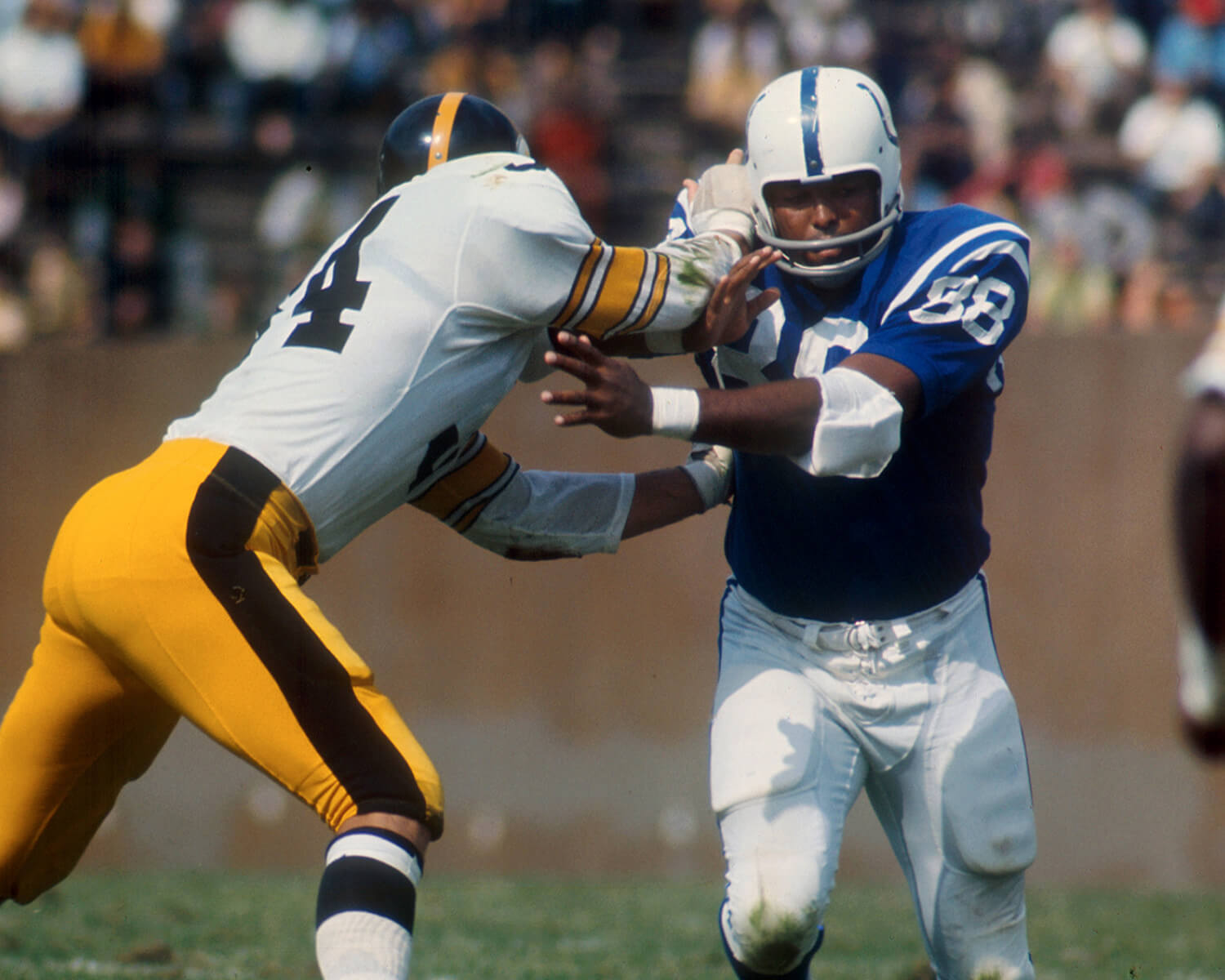

John Mackey (left, No. 88), Tom Matte (right, No. 41), and Earl Morrall (right, No. 15), close friends whose Memorial Stadium lockers were next to each other, in action against the Pittsburgh Steelers and San Francisco 49ers, respectively. Autopsies revealed both Mackey and Morrall had developed CTE. Matte is currently struggling with cognitive issues likely related to CTE. AP Images

In many ways, the revelation that chronic neurological disorders were plaguing former players, and represented a potential crisis for the NFL, began in Baltimore with John Mackey.

Mackey was the first elected president of the National Football League Players Association after the AFL-NFL merger, and Sylvia Mackey picked up the advocacy ball in the wake of his diagnosis, exposing how little the NFL, with annual revenues estimated at $15 billion today, did to assist former players struggling with dementia. Publicly shamed, the league created what’s since been known as the “88 Plan”—an homage to Mackey’s jersey number—in 2007. Today, it provides up to $130,000 annually for nursing facility care and up to $118,000 annually for home custodial care for former NFL players with a diagnosis of dementia, ALS, or Parkinson’s Disease. At the same time, former Colts Bruce Laird, Jim Mutscheller, and Sam Havrilak, witnessing firsthand Mackey's deterioration and the hardship placed on his family, and frustrated by the lack of attention from the NFL, launched the Fourth & Goal Foundation to help retired players. Although the NFL agreed to increase assistance to retired players with the 88 Plan, it was still denying any link between football and CTE, dementia, and other brain diseases.

In fact, it took a more than a decade for the NFL to budge from their stance, even as Dr. Omalu and researchers at Boston University continued to document the widespread presence of CTE in deceased players. (The hallmark of the disease is an abnormal accumulation of defective tau proteins in the brain.) During this period, the high-profile suicides of relatively young former stars, including ex-Steeler Terry Long, who played alongside Mike Webster, former Philadelphia Eagle Andre Waters, ex-Chicago Bear Dave Duerson, ex-Atlanta Falcon Ray Easterling, and former San Diego Charger Junior Seau continued to stack up. All died by suicide between 2005 and 2012 and were later found to have CTE. It wasn’t until just three years ago, after Boston University identified the disease in 90 of the 94 former players it had studied, that the NFL’s top health and safety officer, under Congressional scrutiny, conceded football’s connection to devastating brain diseases. (Laird, Matte, and others accuse the NFL of taking a page from Big Tobacco’s playbook with its history of pushback and denial of legal responsibility.) Since then, the news for football players has only gotten worse.

According to the latest research from the National Institutes of Health, not only is the risk of dementia for former NFL players five times higher than the general population, the risk of developing ALS is four times higher. Ex-Raven O.J. Brigance, who was diagnosed with ALS 12 years ago, is hardly the only recent example. Ex-San Francisco 49er Dwight Clarke, who made perhaps the most famous catch in NFL history in the 1981 NFC Championship, battled ALS before his death last year. Studies show similar increased risks for Parkinson’s and Lewy Body Disease.

The most urgent news, however, pertains to kids: Participation in youth football is now also linked to a significantly greater likelihood of a CTE diagnosis after death. Of the 211 deceased former high school, college, and professional football players diagnosed with CTE in a 2018 Boston University study, those who had started participating in tackle football before age 12 displayed an earlier onset of cognitive, behavior, and mood impairment by an average of 13 years.

Since CTE is found almost exclusively in athletes who play contact sports, what does it mean for the future of football?

For starters, it’s already slicing into the profit margins of NFL team owners. More than $681 million in claims to date have been paid after the league chose to sign a broad settlement rather than litigate hundreds of separate lawsuits brought by former players, who were alleging the NFL had hidden what they knew about the link between repetitive head trauma and brain disease. As of last month, there have been 126 confirmed CTE cases, and a staggering 477 Alzheimer’s, 165 Parkinson’s, and 55 ALS diagnoses asserted by former players or their representatives. The vast majority of these claims have already been paid or are on their way to approval. Another 407 players have received compensation after other neurological impairment diagnoses, with still more cases in process.

Active NFL players are taking notice, too. A number of top players have begun leaving the game early. Among them are former Ravens linemen Eugene Monroe, who retired in 2016 at 29, and John Urschel, who retired in 2017 at 26. Both said their decision was led by brain trauma-related concerns. (Urschel, who is pursuing a PhD in math at MIT, made his announcement two days after the release of the study that found CTE in 110 of 111 former NFL players. He said an earlier concussion had hurt his ability to do high-level mathematics for several weeks.) Retired former Ravens tackle Michael Oher, 31, whose life story was chronicled in the film The Blind Side, and former Ravens star running back Jamal Lewis, 40, have each expressed fears they’re experiencing brain-injury related symptoms, with Lewis admitting he’s had suicidal thoughts since his career ended. “The last 18 years have been full of traumatic injuries to both my head and my body,” Monroe wrote in The Players’ Tribune, explaining his decision. “I’m not complaining, just stating a fact. Has the damage to my brain already been done? Do I have CTE? I hope I don’t, but over 90 percent of the brains of former NFL players that have been examined showed signs of the disease. I am terrified.”

Two weeks before the start of this season, former Ravens All-Pro fullback Le'Ron McClain issued an early Saturday morning plea for help on Twitter: “I have to get my head checked. Playing fullback since high school. It takes too [expletive] much to do anything. My brain is [expletive] tired. NFL, I need some help with this [expletive]. Dark times and it’s showing. [Expletive] help me please! They don’t care. I had to get lawyers, man!”

Hampering football’s long-term viability—its pipeline of young athletes—multiple states in the past two years, including Maryland, have introduced legislation to ban youth tackle football. That legislation has yet to go anywhere in Annapolis, but ultimately it may not matter. The number of boys playing tackle in the U.S. fell almost 20 percent between 2009 and 2015. American mothers and fathers clearly had begun recognizing the science before the NFL did.

“Howard County Recreation and Parks, among others, will tell you the numbers are dropping,” says Howard County state delegate Dr. Terri Hill, who drafted the youth tackle football ban in Maryland with the help of then University of Baltimore law student Madieu Williams, a former NFL safety. “I don’t think the conversation over CTE and youth football is over; I think it’s just starting. The U.S. Soccer Federation has already banned heading below age 12. As a society, we love football. I like football,” she continues. “But it’s not a binary choice between youth tackle football and the values instilled through team sports. There's touch and flag football and other sports.”

Femi Ayanbadejo, who played 10 years in NFL, earning a Super Bowl ring with the Ravens in 2000, said the possibility of brain injury wasn't a subject discussed in NFL locker rooms when he retired in 2007. “It is now,” says Ayanbadejo, whose brother also starred for the Ravens. He adds that while he believes the game is being made safer, with less tackling at practices, for example, he wouldn't let his own son play football until he turned 13 this year. “He's a very good athlete, but you should play other sports at a young age. I didn't play football until high school and then I only played two years.”

The most urgent news, however, pertains to kids: Participation in youth football is now also linked to a significantly greater likelihood of a CTE diagnosis after death.

Typically, the cause of the kind of early dementia her husband suffered from is difficult to pinpoint, but Sylvia Mackey began connecting the dots at the annual Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremonies in Canton, Ohio. She and John continued to attend each year even as his diagnosis became public knowledge and his dementia worsened. By 2003 and 2004, wives of other Hall of Fame players quietly began approaching her with concerns regarding their own husbands’ behavior and mood swings at the annual August event, inquiring when she first began noticing signs of distress. In hindsight, Sylvia, who at 77 still works as a flight attendant and recently attended Baltimore Raven Ed Reed’s induction into Canton, says the early warning signals—forgetfulness, depression, inexplicable financial decisions, rude behavior at a family funeral—began arising when John was in his late 30s and 40s. “I’d see the wives walking toward me and I knew from the look on their faces what they were going to ask me,” she says. “It was heartbreaking. The thing is, the Hall of Fame is such a small group of players. Only about 300. Just based on the number of wives that were coming to me, I knew there was a problem with playing football.

“When Gene Hickerson [former Cleveland Brown guard] was inducted, Jim Brown pushed him out in a wheelchair. He didn’t know where he was. I’ll never forget that ceremony.”

How many more will there be to come? Many football players who never made it to the NFL have reason to worry. BU studies have found CTE in more than 99 percent of former NFL players, but also 91 percent of former college football players, and 21 percent of high school players. “We hear every day from former players concerned about lasting brain injury,” Nowinski says. “The bottom line is more work needs to be done.” He believes the day of reckoning for the sport will come when technology will be able to identify CTE in living athletes and enable brain scans of a high school football team. “If we find one, more than one, 10 percent of the kids who already have CTE, that should dramatically change behaviors or what people are allowing their children to play,” he told PBS’s documentary series Frontline.

Only recently, after a conclusive diagnosis was made linking the cause of memory, behavior, and dementia issues to football, did former players and their spouses begin to follow Sylvia Mackey’s courageous example and come out publicly. However, at least in Baltimore, before her husband’s problems surfaced, it was widely known, and reported, that former Colts were dealing with dementia and other issues. In particular, there was Bill Pellington, who died in 1994, and Don Shinnick, who died in 2004. Pellington ran and owned the popular Iron Horse restaurant in Timonium for 20 years after his playing days ended. As far back as 2000, venerated former Sun sportswriter John Steadman pointed to football as the likely culprit. This was shortly after former linebacker Steve Stonebreaker had died by suicide, positioning his head on a pillow next to an automobile exhaust pipe inside a locked garage. It all fell on deaf ears.

“Bill Pellington, when he started exhibiting certain behavior, people said, ‘Oh yeah, he drinks too much’ or ‘He’s hardheaded,’” Laird, the former Colt safety, says. “They didn’t care enough to take serious look at what he or other players were going through. It was, ‘They can’t adjust to life after football.’ Well, there might be a good reason for that.”

Which raises another question: Do the consequences their gridiron heroes face as a result of those Sunday afternoon battles matter to football fans? Will it turn them away from the game? It doesn’t appear that way at the moment. Despite some attendance blips, TV viewership is rising again, and overall NFL revenue keeps climbing and is still marching toward Commissioner Roger Goodell’s stated goal of $25 billion by 2027. Ravens owner Steve Bisciotti certainly seems optimistic about the game’s future—the team just finished a $120-million stadium renovation, including a new sound system, a pair of new 200-feet-wide and 36-feet-high ultra-high definition video displays behind each end zone, upper deck escalators and elevators, a redesigned club level, and updated suites.

Over the past few seasons, the NFL has tried to mitigate the damage on the field. They’ve reduced the number of kickoffs and now penalize helmet-to-helmet contact. More rules limit live hitting during practices. They’ve also established concussion protocols, but the real issue is the volume of repetitive hits sustained over the course of a tackle-football career. As research into repetitive head trauma, CTE, and related diseases continues, it remains unclear whether tackle football can be played safely at all.

Dr. Jennifer Coughlin, assistant professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, has been utilizing new brain imaging techniques in studies of recently retired and former NFL players. She hypothesizes that the excessive build up of tau proteins seen in CTE cases may be the result of the immune system’s response to repetitive blows. It could help explain why some players—former Colts Artie Donovan and Gino Marchetti, for example—did not exhibit signs of dementia into their 80s and 90s, respectively, before passing. Their brains, for whatever reason, were somehow able to mitigate the excessive build up of proteins, which, over time, harden like concrete into key passageways.

Certainly, it does not appear youth tackle football should be played, researchers say.

The Concussion Legacy Foundation strongly recommends delaying enrolling children in tackle football until the age of 14. The initial research is so concerning that they’ve launched the Flag Football Under 14 campaign to educate parents. “Think of a bobble-head effect,” says Dr. Robert Cantu, professor of neurology and neurosurgery and co-founder of the CTE Center at the Boston University School of Medicine. “Kids’ heads are heavy, their necks aren’t strong enough to absorb the shock—and their brains are still developing. Exposure to repetitive head trauma is too risky. More worrisome is what we don’t know. How will the hits absorbed by a 9-year-old today be felt at 30, or 50?”

“do I wish he’d have taken the basketball scholarship?” judy Matte asks rhetorically. “i guess i do now. these were supposed to be our golden years.”

TOM MATTE, who starred for 12 years with the colts, AND HIS WIFE, JUDY, IN THEIR HOME IN Baltimore county.

The crazy thing, Tom Matte tells me later in his den as he shows off a prized Colts helmet signed by former teammates, is that he doesn’t have any knee, back, or shoulder problems. For a former NFL running back who just turned 80, he looks strong and healthy. His gait is remarkably smooth. “No hip replacements. None of it,” he says. “I had some cartilage removed from my knee in college, and even that never bothered me again. Everything except my head is in good shape.”

The couple is planning an upcoming trip to the Delaware beaches, and Judy says she’s grateful that, while Tom’s memory and cognitive issues have been getting worse, “it’s happening slowly.” She recalls running into Earl Morrall, who shared quarterbacking duties with Johnny Unitas on those terrific late ’60s teams, years ago at a supermarket. Morrall and his wife were old friends, but Earl couldn’t place Judy even after she introduced herself. She notes that Tom takes the same anti-depressant and anti-anxiety medication that many people with Alzheimer’s are prescribed. “He has the symptoms, checks all the boxes. We have one of those Amazon Alexas in the kitchen, so he’s not asking me questions all the time. He asks it a couple of times a day what day of the week it is.” She recalls that when they married, Tom promised he’d just play two years of pro ball. Then it became five, so they’d be vested in the pension. Those NFL benefit dollars, about $3,300 a month—typical for pre-1993 players—aren’t enough anymore. “We’ve lived here 25 years, but now we do have to sell the house,” she says. They’d begun dating in high school in Ohio and continued through college while he went to Ohio State to play for Woody Hayes and she attended Wittenberg University. “Only 50 miles away, which meant I could drive on weekends to see her,” Tom says with a smile. “She’s been my mainstay. She has saved my ass.”

“Do I wish he’d taken the basketball scholarship to the Naval Academy he’d been offered?” Judy asks rhetorically. “Well, you’re supposed to be appreciative of what you have, and I am. But I guess I do now. These were supposed to be our golden years.”

Sylvia Mackey, meanwhile, has thought hard over the years about her grandchildren playing the game. Her oldest grandson was in middle school, playing tackle football and wearing No. 88 like his grandfather, when John’s life fell apart. “His mother pulled him out right away and pushed him into basketball,” Sylvia says. “And I agreed. He ended up playing at Princeton and going to the NCAA tournament. You can’t do better than that.” Her youngest grandson, who is 8 years old and named John after his grandfather, has played flag football “and wants to play more football,” she says. “I don’t dislike football or blame anyone for what happened to John, and I don’t think tackle football or pro football is going anywhere any time soon. People love it too much. But as far as I’m concerned, and I know his mother, my other daughter, feels the same way, flag football is the only football he will ever play.”