Sports

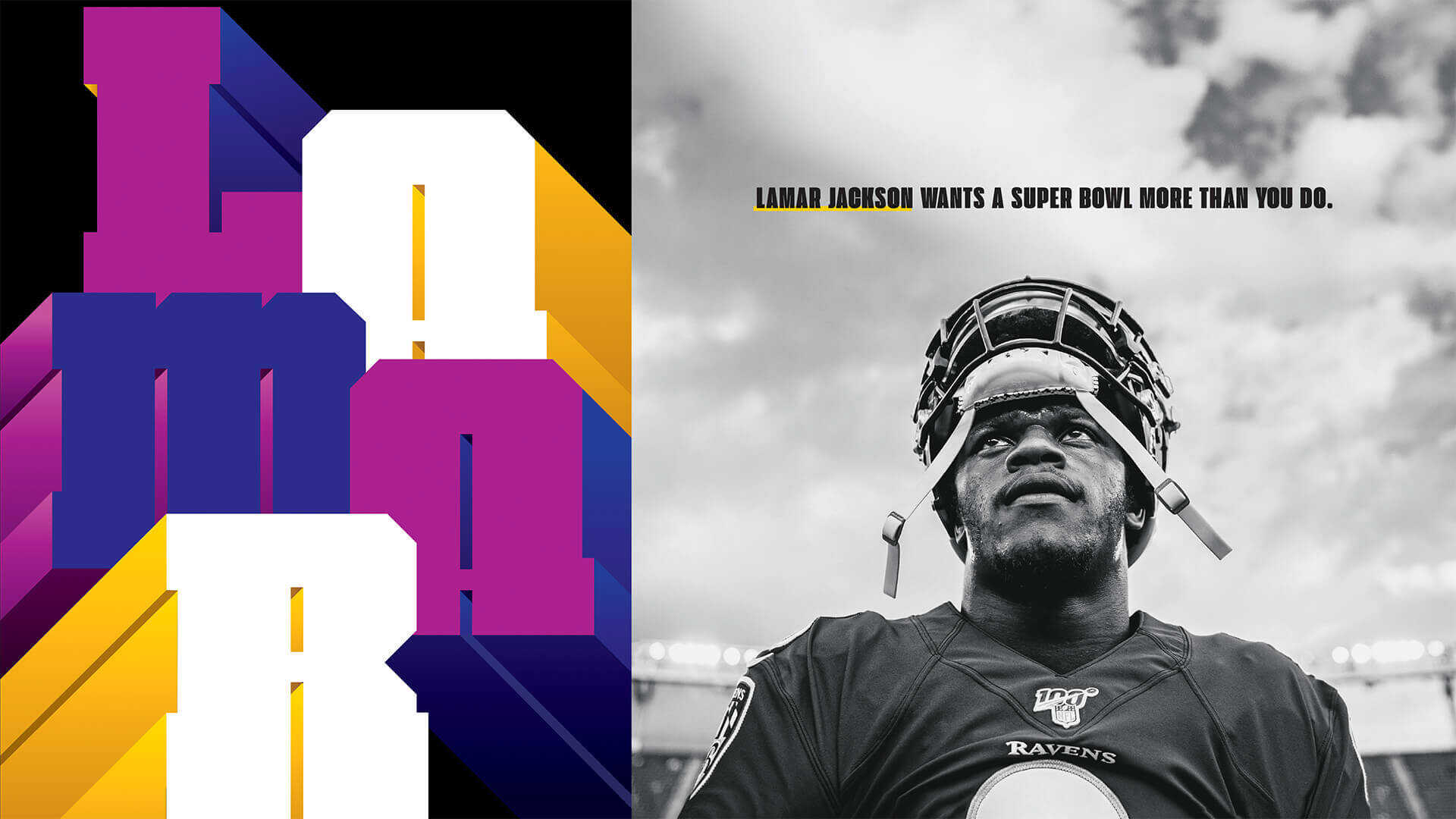

Lamar Jackson wants a Super Bowl more than you do.

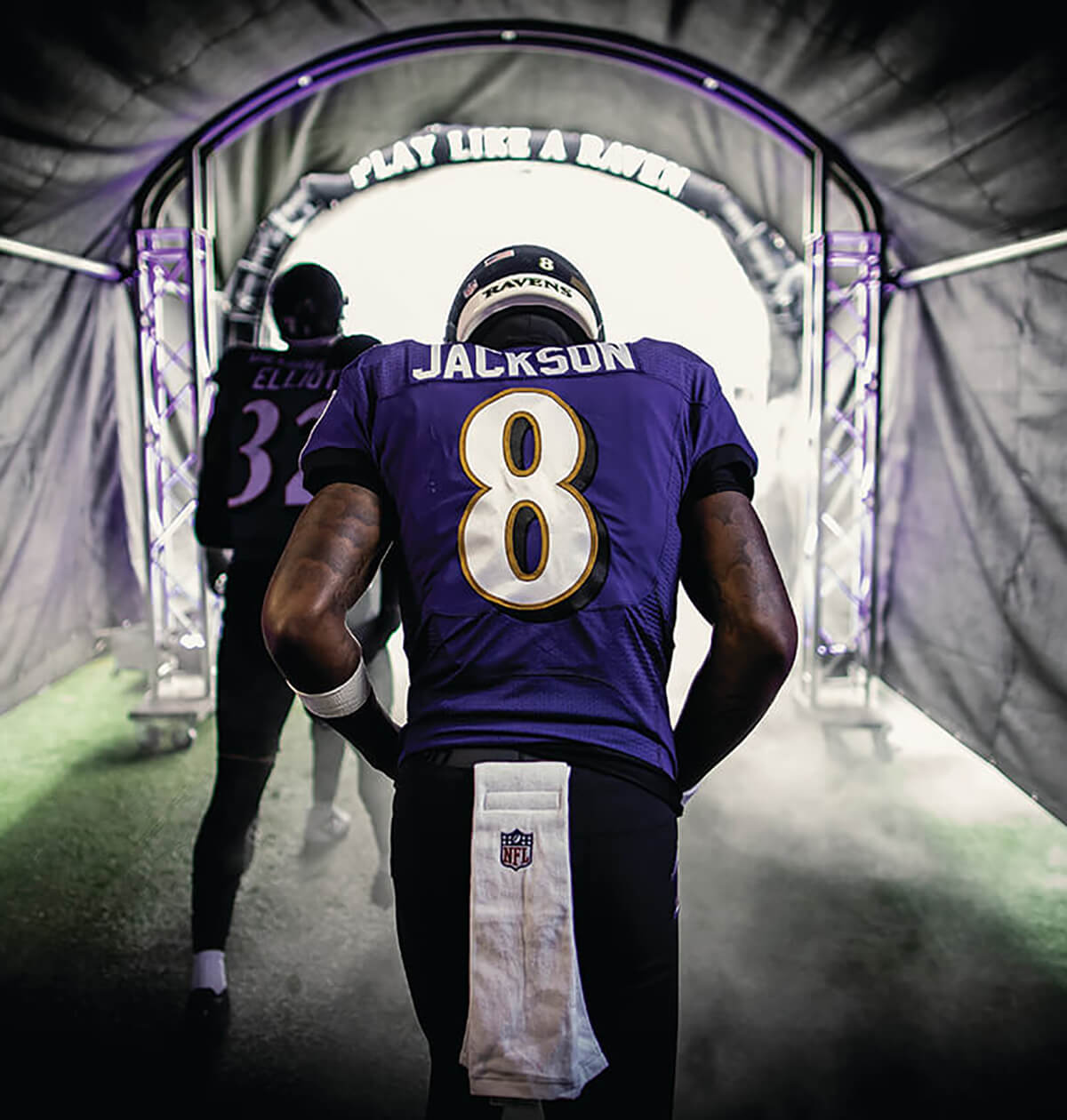

Above: Jackson on the

field at a preseason

game at M&T Bank

Stadium, 2019.

AYBE IT’S EVOLUTION,

or how God planned it, but

scientists say the human brain is

wired in a way that often makes

us remember severe pain longer

than we enjoy great pleasure.

Apparently the same is true even

if you’re a little bit superhuman,

like an Avenger, or Lamar Jackson on

the gridiron. It’s five months after the

Ravens’ 17-3 loss to the Buffalo Bills in

the second round of the NFL playoffs, and the

24-year-old star, wearing a team-issued hoodie, is

talking to reporters via video from the team’s practice facility

in Owings Mills. “I’m still ticked off,” the quarterback

says, sitting in front of a black backdrop dotted with Ravens and

Under Armour logos. “I’m going to always be ticked off losing.”

AYBE IT’S EVOLUTION,

or how God planned it, but

scientists say the human brain is

wired in a way that often makes

us remember severe pain longer

than we enjoy great pleasure.

Apparently the same is true even

if you’re a little bit superhuman,

like an Avenger, or Lamar Jackson on

the gridiron. It’s five months after the

Ravens’ 17-3 loss to the Buffalo Bills in

the second round of the NFL playoffs, and the

24-year-old star, wearing a team-issued hoodie, is

talking to reporters via video from the team’s practice facility

in Owings Mills. “I’m still ticked off,” the quarterback

says, sitting in front of a black backdrop dotted with Ravens and

Under Armour logos. “I’m going to always be ticked off losing.”

Even though he’s an introvert by nature—not necessarily a fitting inclination for someone in the spotlight, nor the type of personality that comes to mind given his electrifying skills on the field—Jackson is personable and looks comfortable speaking to the media. He playfully calls reporters by first name before answering their questions (“Mr. Jamison,” he says to ESPN beat writer Jamison Hensley; “Gustavo!” Jackson says later, enthusiastically repeating the name of a Spanish radio reporter) with a touch of humor and unvarnished, unrehearsed insight that makes for good sound bites. For those wondering, the guy who once chirped back at his critics, “Not bad for a running back,” in a press conference after throwing five touchdowns in the 2019 season-opener, is the same person in private. “The personality you see, that’s who he is every single day,” says Ravens quarterback coach James Urban, who spends more time with Jackson than virtually anyone else during the season.

Which makes what comes next in this press conference even more meaningful. As Jackson is asked about the details of the playoff loss against the Bills for the first time since the early exit (remember, he was knocked from the game with a concussion and thus didn’t talk to the media afterward), he leans in and crosses his arms on a table in front of him. He gets serious while explaining how he feels about the end of the Ravens 2020 season. “Everyone hates losing,” he says in the native, rural Florida accent Baltimoreans have come to know. “If you’re cool with losing, then you shouldn’t be playing that sport. Or whatever you did, you shouldn’t be doing it . . . I don’t care how old the game was—I really don’t—I’m going to always remember that loss more than a victory.”

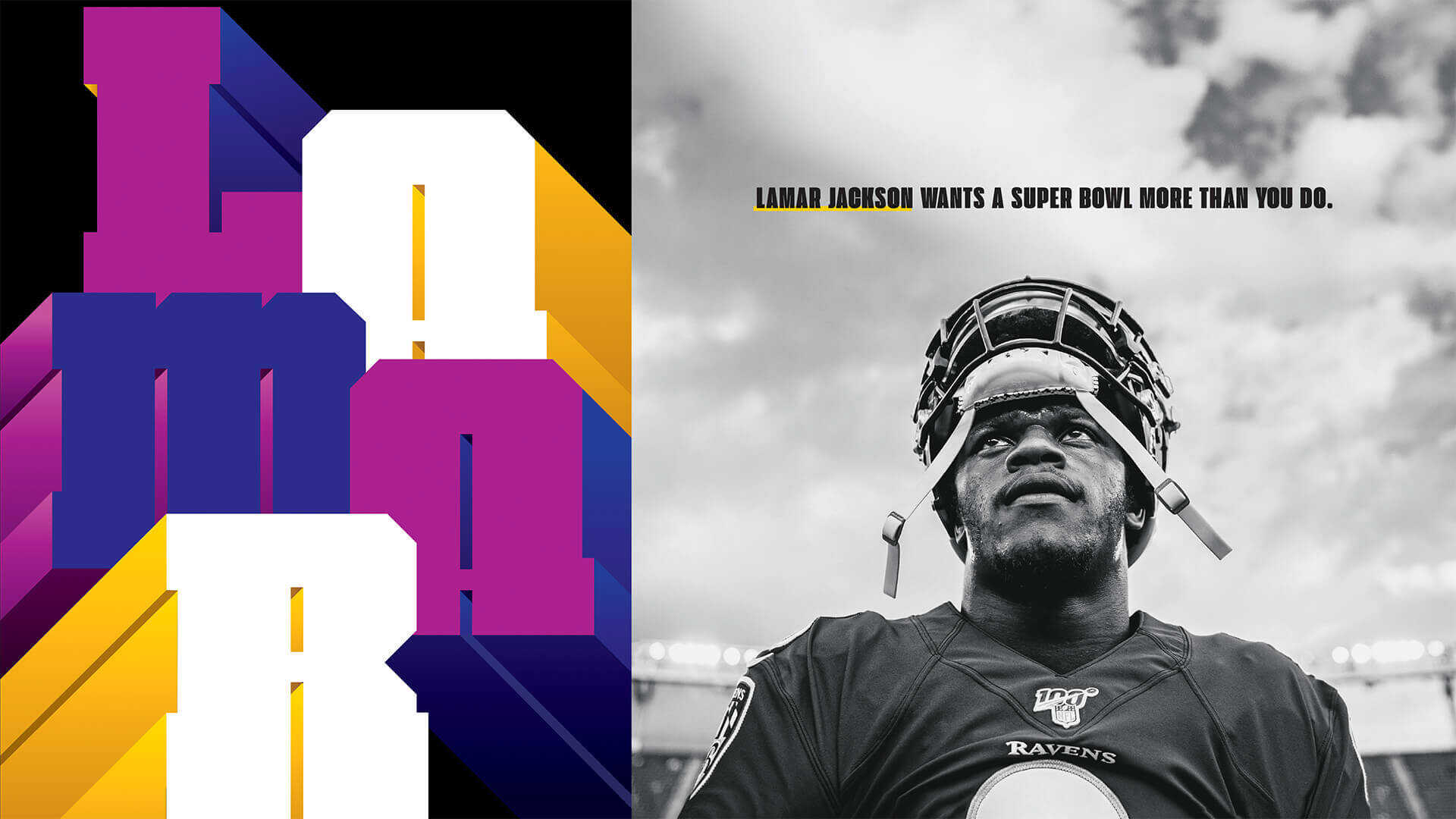

An early portrait

of Lamar as an

NFL rookie, 2018.

he pain. Jackson’s relatively

young brain will remember it.

Not to be flippant, but it’s not

just because of the head injury

sustained by the quarterback,

who otherwise has been remarkably

durable in three years as a

pro, especially considering his

fearless game. In the best of times, Jackson has captured

fans’ imaginations (and the internet’s attention)

with Usain Bolt-like speed in a football uniform

and juke moves that startle us—and defenders.

Along the way, he won 30 games faster than any

quarterback in NFL history. But after an errant shotgun

snap went over his head on the final play of the

third quarter in Buffalo, Jackson needed to use all of

his quickness to just scramble into the Ravens own

end zone, gather the bouncing football, and throw it

away to the sideline to avoid more damage. In the

process, one defender tackled him low, another

high. When he crashed to the ground, the back of

his helmet hit the chilly, hard turf.

he pain. Jackson’s relatively

young brain will remember it.

Not to be flippant, but it’s not

just because of the head injury

sustained by the quarterback,

who otherwise has been remarkably

durable in three years as a

pro, especially considering his

fearless game. In the best of times, Jackson has captured

fans’ imaginations (and the internet’s attention)

with Usain Bolt-like speed in a football uniform

and juke moves that startle us—and defenders.

Along the way, he won 30 games faster than any

quarterback in NFL history. But after an errant shotgun

snap went over his head on the final play of the

third quarter in Buffalo, Jackson needed to use all of

his quickness to just scramble into the Ravens own

end zone, gather the bouncing football, and throw it

away to the sideline to avoid more damage. In the

process, one defender tackled him low, another

high. When he crashed to the ground, the back of

his helmet hit the chilly, hard turf.

The unexpected, upsetting scene that followed—Jackson writhing on his back, his purple No. 8 facing the dark sky above, knees up, as he was tended to by trainers—capped a forgettable sequence late on a Saturday night. Another promising Ravens season had come to a third straight earlier-than-desired end. On the series before he was concussed, Jackson did something shockingly out of character—throwing an interception in the middle of the field in the opponent’s end zone. Not only that, it was returned an NFL playoff record of 101 yards for a touchdown, essentially closing the Ravens chances for a win even before he was hurt.

With the 2021 season approaching, the three points the Ravens offense scored that night amid Jackson’s costly miscues have again prompted some of his keyboard critics to renew their now-familiar refrain: “Lamar can’t win the big one!” They point to his career 1-3 postseason record and unconventional style. “He’s a runner, not a passer,” they say. For better or worse, it’s the chip on Jackson’s shoulder that he has carried with him into offseason workouts and meetings, as well as onto his very active social media accounts, which belie an otherwise private life largely spent around family and close friends. It’s a desire to silence his haters that he carries with him at all times, that fuels his behavior, his thoughts, his every waking decision. In other words, Baltimoreans, he wants to win the biggest game in American sports—a Super Bowl—more than you want him to do it. “We fell short three years in a row since I’ve been here,” he says, “and I’m always seeing teams . . . when they win it, it’s like your whole life just changed. It’s not even a change—it’s the excitement I see, the feeling, holding the trophy up. My mind[set] is just different. I’ve got to get it. I’ve got to get one—at least one.”

Jackson heads

through the tunnel to the field

at M&T Bank Stadium, 2020.

an he do it? It’s a question that’s essentially been

asked of Jackson since he started playing organized

football at age 7 in Pompano Beach, Florida.

Even his father, before he passed away way too

early at age 31 of a heart attack, questioned his

wife’s assertion that young Lamar could throw a

football the distance from the backyard of the

family home to the street. He did it. “I told you,”

Jackson’s mother, Felicia Jones, said. “I told you.” From there, for

whatever reasons, veiled racial stereotyping included, coaches and

scouts more enamored with Jackson’s blazing speed have repeatedly

labeled him not suited for quarterback. As a teenager, Jackson transferred

high schools, in part to play quarterback, and led previously

unheralded Boynton Beach High to the Florida state playoffs. At the

University of Louisville, after hearing her son had fielded punts at a

practice his freshman year, his mom famously called then-coach

Bobby Petrino and reminded him of the recruiting promise he made

that her son would only play quarterback. Jackson, of course, would

go on to win the Heisman Trophy, awarded to the nation’s best college

player. And we all know the story of NFL Draft process and selection

night. The Ravens traded up to get Jackson with the 32nd pick in the first round, meaning every other team passed on him, including

the Ravens, initially, who had selected tight end Hayden

Hurst with an earlier first-round pick.

an he do it? It’s a question that’s essentially been

asked of Jackson since he started playing organized

football at age 7 in Pompano Beach, Florida.

Even his father, before he passed away way too

early at age 31 of a heart attack, questioned his

wife’s assertion that young Lamar could throw a

football the distance from the backyard of the

family home to the street. He did it. “I told you,”

Jackson’s mother, Felicia Jones, said. “I told you.” From there, for

whatever reasons, veiled racial stereotyping included, coaches and

scouts more enamored with Jackson’s blazing speed have repeatedly

labeled him not suited for quarterback. As a teenager, Jackson transferred

high schools, in part to play quarterback, and led previously

unheralded Boynton Beach High to the Florida state playoffs. At the

University of Louisville, after hearing her son had fielded punts at a

practice his freshman year, his mom famously called then-coach

Bobby Petrino and reminded him of the recruiting promise he made

that her son would only play quarterback. Jackson, of course, would

go on to win the Heisman Trophy, awarded to the nation’s best college

player. And we all know the story of NFL Draft process and selection

night. The Ravens traded up to get Jackson with the 32nd pick in the first round, meaning every other team passed on him, including

the Ravens, initially, who had selected tight end Hayden

Hurst with an earlier first-round pick.

Lamar with his mother, Felicia Jones, after winning the Heisman Trophy in 2016.

Even now—after a 30-7 regular-season record, 7,085 passing yards, 2,906 rushing yards, and 87 combined touchdowns in three years as a pro; Jackson’s unanimous selection in 2019 as the NFL’s Most Valuable Player; and a library of meme-inspiring highlights—he still has doubters. Just this offseason, the oft-cited Pro Football Focus website notably left Jackson out of its list of the league’s Top 50 players. They said he didn’t grade well in their pass-heavy quarterback rating metrics. That said, you also have to believe Jackson would’ve cracked the list if his postseason performances were better. Each of the three losses was its own brand of ugly (look up the 2018 Los Angeles Chargers and 2019 Tennessee Titans games, if you dare). Yet, none of this means Jackson isn’t a great quarterback capable of winning an NFL championship. He is. Nor does it mean that he doesn’t have the full-throated support of the locker room and the decisionmakers behind the club. He does. “People want to follow him. He’s like the Pied Piper,” Ravens president Dick Cass told Baltimore. “We’re all in on Lamar Jackson.”

Many Las Vegas sportsbooks give the Ravens 14-to-1 odds of winning the Super Bowl this year, fifth best of 32 NFL teams, and Jackson is about to be paid the going rate for an elite player at his position. In April, without a second thought, the Ravens picked up his $23-million fifth-year option on his rookie contract, as Jackson—who is his own agent, a story itself—and general manager Eric DeCosta work toward a longerterm deal that could pay him closer to $40 million per season. (Note: The timing of some of this may be predicated on Jackson getting back on the field after a pre-season positive test for COVID-19 just before this issue went to print.)

In professional sports, it’s easy to say it’s all about the money for the adults involved. And for many, it certainly can be. Not Jackson. First, he is a kid at heart in many ways. (How many rap singalongs can one guy post online, after all?) Second, by all accounts, a desire for a fat paycheck has never been what has gotten him out of bed in the morning. “What’s his legacy going to be as a quarterback?” says Ravens head coach John Harbaugh. “That’s what he’s focused on.” Apparently, it’s been that way from Day 1. Urban recalls walking off the practice field with Jackson, late in the week near the middle of Jackson’s rookie season, just before he unseated incumbent and Super Bowl XLVII MVP Joe Flacco as the starter and led the Ravens to their first playoff appearance in four years. The coach and the young QB had just finished one-on-one throwing drills. No one else was around. “I can see every day you’re getting better and better,” Urban told Jackson. “Just keep working. You are going to love Sundays in this league.” Jackson paused and said, “Coach, you’re going to love me on Sundays in this league.”

“It was an awesome, quiet confidence,” Urban says. “He’s a very positive-minded person. He’s an energy giver. It was like, ‘Let’s go, you guys wanted me. I’m going to prove you right.’”

Jackson cuts back during a home game against the Jaguars in 2020.

There’s no getting around that Jackson’s personality, unique ability, and the simple facts of his backstory—the son of a single mom, growing up in a disinvested neighborhood, overcoming doubters—makes him easy to root for. But plenty of other talented people on a similar path have lost their way before reaching their biggest goals. Still, even as an MVP by age 22, not much seems to go to Jackson’s head. “I won’t change on people unless they change on me,” he said this offseason. He doesn’t have any major endorsement deals, aside from Oakley sunglasses (which makes his helmet visor), and sells his own branded Era 8 Apparel that features imagery of the endangered African wild dog (designed in part to highlight their plight). He lives with his mom and three younger siblings in a house near the end of a quiet, mansion-lined street not far from the Ravens practice facility; he reads Bible verses every day; credits his faith for keeping him humble; and has dated his girlfriend, Jaime Taylor, since they met in 2017 at Louisville. He’s fiercely loyal to his friends from back home in Broward County, Florida, including lightning-rod rapper Kodak Black and teammate and wide receiver Marquise “Hollywood” Brown.

On his first night back in Baltimore before training camp near the end of July, with stories circulating everywhere about the status of his future contract, Jackson went to Azumi in Harbor East with his buddy Brown and the two men toasted to a hopeful Super Bowl win. In the next 24 hours on social media, Jackson posted a funny Instagram video from the Ravens locker room of bald-and-goateed tight end Nick Boyle, and appropriately chose former WWE wrestler “Stone Cold” Steve Austin’s entrance music to accompany it. That night, Jackson also shared video of kids doing wheelies on bicycles in the parking lot outside of a Party City in Owings Mills. “Lamar is so authentic and true to who he is and where he comes from,” says CBS sideline reporter and analyst Evan Washburn, an Annapolis native who has covered multiple Super Bowls and interviewed Jackson nearly a dozen times. “He’s like if your best friend from high school became the NFL MVP, and nothing changed.”

No one has ever questioned if Jackson is likeable or fun to be around. People call him Lamar because they feel like they know him intimately—and they basically do. Back in 2019, for example, shortly after a 47-yard touchdown run against the Cincinnati Bengals, punctuated by a jaw-dropping spin-move away from two tacklers, David Alima, the owner of The Charmery ice cream shops, decided to offer a new flavor, Lamarshmallow Swirl. (It was a roasted blueberry base with marshmallows throughout.) It wasn’t just because of Jackson’s on-field ability, but because Alima had also been impressed a year earlier, when the then 21-year-old rookie had made a small gesture toward one of Alima’s high-school-aged employees. The Charmery crew was serving the team ice cream after a training camp practice when the kid (Tony) asked for a photo. “What’s your name?” Jackson had asked him back. “It was a little different,” Alima says, “like let me make a quick connection here. From then on, I’ve been a huge Lamar fan.”

You might also remember Jackson’s quest for banana pudding the Friday afternoon before his second career playoff game in January 2020 at home against the Titans, which led him to Miss Carter’s Kitchen, a soul and seafood restaurant on Edmondson Avenue. They didn’t have any pudding available, but Jackson and teammates Marcus Peters and Earl Thomas spent $500 on other various dishes, like pasta with lamb chops, turkey wings, and collard greens.

The Ravens clearly got it right with their bold draft day move to acquire Jackson, a young talent that the franchise can potentially build around for another decade. The team has really rallied around him as a leader as well. “I don’t think there’s a doubt in anyone’s mind that when you see Lamar Jackson play, you want to do everything for him, protect him and continue to see the magic that he displays on the field,” says offensive lineman Alejandro Villanueva, who signed with the Ravens this year after six seasons with the rival Pittsburgh Steelers. “Because it not only makes the game of football incredibly fun for the fans and for everybody out there, but it also wins you a lot of football games.”

Off the field, sources close to the team say that Jackson has privately visited at-risk youth in the city, mentoring them in one-on-one sessions that he doesn’t want publicized. “I think over time he will become a significant unifying force in our city,” Cass says. “He’s a kind of figure that cuts across everything that divides us, whether it’s age, race, class, or politics. He brings people together, and that’s what you really want to see from a team.”

All that said, Jackson and the Ravens face practical challenges in pursuit of a Super Bowl, which would be the franchise’s third in its 25-year history. We know Jackson’s strengths. He’s one of the fastest athletes we’ve ever seen, can change direction quicker than a politician seeking reelection, and breathe life into a going-nowhere play like no one else in the game. “He’s faster than the whole team, can’t tackle him,” Titans head coach Mike Vrabel told his assistants on the sideline after Jackson broke free for a game-changing 48-yard touchdown run in the Ravens 20-13 first-round playoff win last January, Jackson’s first NFL postseason victory. But the scouting report is also out on how to successfully defend a Jackson-led offense. The Bills revealed the blueprint, most recently: Don’t let the elusive quarterback and running backs run wild on the edges of the field, and when Jackson steps back to throw, expect him to look between the hashes to his tight ends, like favorite target Mark Andrews. If you can get a few turnovers (interceptions, fumbles, or three-and-outs) against the Ravens, and get ahead, then your chances for a win rise more than they would against other conventional passing offenses.

The Ravens unique run-heavy scheme (55 percent of their plays have been on the ground since Jackson became the starter) isn’t best suited for scoring points as quick as say, Kansas City and other high-scoring offenses on the schedule this year, with a wild 47-42 win over Cleveland last year on a Monday night a notable exception, and perhaps a sign of things to come. “They can win the three to four games they need to win a Super Bowl,” says NFL Network analyst Daniel Jeremiah, a former college quarterback and Ravens scout from 2003 to 2006. “The problem is it’s just a little bit more of a narrow path, because if the game gets away from them and they’re in a throw-only mode, that’s not their strength.” You have to go back to 2005 to find an NFL team that ran as much as the Ravens and won a championship. That was (unfortunately) the Pittsburgh Steelers, who ran 57 percent of the time. But that’s not to say it can’t be done. The average run-rate of the last 10 Super Bowl winners is 42 percent, but the 2013 Seattle Seahawks did it with a league-leading 52 percent, powered by the NFL’s top-ranked defense.

Jackson is often unstoppable as a runner, and he could always throw it far (grainy video from high school shows him tossing a near-football field-length bomb). But dissecting a defense through the air like Tom Brady or connecting on deep routes all over the place like a Peyton Manning is not Jackson’s thing. “To think that he’s going to be this pocket proficient passer, that’s just not Lamar,” says former Ravens Super Bowl-winning coach Brian Billick, who coached the then-highest scoring offense of all time as a Minnesota Vikings assistant in 1998. “He’s not a 50-throws-from-the-pocket guy. I think he’s probably about as good as he’s going to be as a passer. But this is what he is, and it’s pretty darn good.” That’s not going to stop Jackson from trying to add more depth to his game, however. He and Urban have talked about how greats in other sports, like Michael Jordan, worked on developing a particular skill each offseason. In workouts with private coaches this summer, Jackson says he focused on his footwork. “Making sure I stay open,” he said, meaning angling his front left foot so he can face his target when he throws and add more power using his hips, “so I can put a little tight spiral on the ball.” The goal is better accuracy.

The Ravens coaches and front office also hope new wide receiver talent, highlighted by first-round pick Rashod Bateman, a former Big Ten receiver of the year from Minnesota, helps stretch defenses. And that a revamped offensive line and the return of All-Pro left tackle Ronnie Stanley from ankle injuries will better protect their superstar. Urban says that developing timing with his wideouts is the key balance they’re looking to find. “This is what a 10-yard out feels like. This what an 18-yard dig route feels like,” Urban says. “We’re not taking away what genetics and the good Lord above gave him. What we’re trying to do is establish a consistency of the mechanics when the pocket is clean and when you can drop back and throw it on time. That’s what we’re chasing.” Well, that and, you know . . . a Lombardi Trophy.

Lamar

with his friend and

teammate, wide

receiver Marquise

“Hollywood” Brown,

during practice in

2020

ack in Florida last month, over a weekend at the

public park where he grew up playing, Jackson

hosted a “Fun Day With LJ.” It was actually two

days, and featured a 7-on-7 youth tournament,

moon bounces, free snacks, music, and a chance

to see a local hero. Hundreds of kids showed up

for the grassroots event. Despite county police

protection, Jackson was mobbed near his car

when he was spotted the first day. During part of the second day,

Jackson threw footballs to kids, ran pass routes, and covered others

as a defensive back, the type of genuine, down-to-earth thing Jackson

has become known for.

ack in Florida last month, over a weekend at the

public park where he grew up playing, Jackson

hosted a “Fun Day With LJ.” It was actually two

days, and featured a 7-on-7 youth tournament,

moon bounces, free snacks, music, and a chance

to see a local hero. Hundreds of kids showed up

for the grassroots event. Despite county police

protection, Jackson was mobbed near his car

when he was spotted the first day. During part of the second day,

Jackson threw footballs to kids, ran pass routes, and covered others

as a defensive back, the type of genuine, down-to-earth thing Jackson

has become known for.

Jackson makes time to sign autographs for fans after the Ravens defeated the Pittsburgh Steelers at Heinz Field, 2019.

It was fun, but the critics were quick to pounce when videos hit social media. Most notably, Mike Florio of news site Pro Football Talk wrote, “As he closes in on a contract worth upwards of $40M per year, Lamar Jackson probably shouldn’t be doing DB/WR drills on an asphalt basketball court.” Former Ravens tight end Shannon Sharpe piled on during his Fox Sports morning show a few days later. “Why Lamar?” Sharpe said. “It’s not worth it. Don’t mess your money up being dumb. You’re better than this, brother.” To which Jackson replied on Twitter, you’re missing the point: “Itz better to have them kidz out there having fun than playing with gunz and [a poop emoji] so next year we running it back with even more fun.” And to the 2.8 million who follow him on Instagram @new_era8, Jackson wrote in purple font on a black background: “I need that Super Bowl like tomorrow cause I’m sicka these peoplez.”

Not that he necessarily needed extra motivation. Losses, in football or life, don’t go away easy, but the painful experiences can also often enhance great pleasures when they come. Before all the silly fun-day business, Jackson said he already had good reasons for wanting to win an NFL championship. Bragging rights, sure, but more importantly, he said, what he seeks is a certain long-term peace of mind, so years from now when he’s maybe a bit slower and gray he can revel in the glory days. “So I can feel accomplished and be like, ‘We did what we were supposed to do,’” Jackson says. “Then I can sit back when I have grandkids and talk my trash like old heads do. Talk my trash to the younger generation. Then my legacy . . . then we can talk about my legacy.”

A Lamarvelous Era

April 2018

The Ravens take Jackson with the 32nd overall pick in the NFL Draft. “They’re going to get a Super Bowl out of me, believe that,” Jackson, the 2016 Heisman Trophy winner from the University of Louisville, says on stage to interviewer Deion Sanders.

August 2018

Jackson dazzles in his first preseason game at M&T Bank Stadium, with an ankle-breaking touchdown run and 119 passing yards. “He does seem poised for a rookie,” coach John Harbaugh says.

November/December 2018

Incumbent starting quarterback and Super Bowl XLVII MVP Joe Flacco suffers a hip injury against the Steelers, and Jackson goes 6-1 as a starter in Flacco’s place, leading the Ravens to the playoffs for the first time in four seasons.

January 2019

A few days shy of his 22nd birthday, Jackson becomes the youngest QB to ever start an NFL playoff game. The Ravens lose, 23-17, at home to the Los Angeles Chargers. At one point in the third quarter, Jackson had 25 passing yards.

September 2019

It’s Jackson’s team—Flacco was traded in the offseason—and the second-year QB throws five TD passes in a 59-10 season-opening win at the Miami Dolphins. “Not bad for a running back,” he says after, to his critics who say he can’t throw.

October 2019

An in-stride spin-move against the Cincinnati Bengals goes viral, just the start of the highlights and headlines to come en route to winning league MVP, the first offensive player in Ravens history to do it.

January 2020

After a first-round playoff bye, the Ravens lose to the Tennessee Titans, 28-12, at home. Jackson accounted for 500 yards of offense, but also three costly turnovers.

November/December 2020

Jackson is placed on the COVID-19 list. A few weeks later, in a thrilling 47-42 win over the Cleveland Browns, he missed part of the game with leg cramps. The Ravens finish the regular season 11-5.

January 2021

Jackson gets his cathartic first playoff victory, throwing for 179 yards and running for 136 in a 20-13 win over the Titans in a rematch of the previous year’s postseason game. The following week, the Ravens fall to the Buffalo Bills 17-2 in the AFC Divisional Round, two wins short of a Super Bowl appearance.

July 2021

As training camp begins, Jackson tests positive for COVID-19 for the second time in eight months. He misses 10 days of practices, per NFL rules, indicating he hasn't been vaccinated. After returning, he's noncommittal about doing so. "We'll see," he says.