Sports

Regardless of His Last Name, Wes Unseld Jr. Had to Pay His Dues in the NBA

It took 24 years for the Catonsville native to land a head coaching job. Now, he's following in his late father’s Hall of Fame size 16+ footsteps.

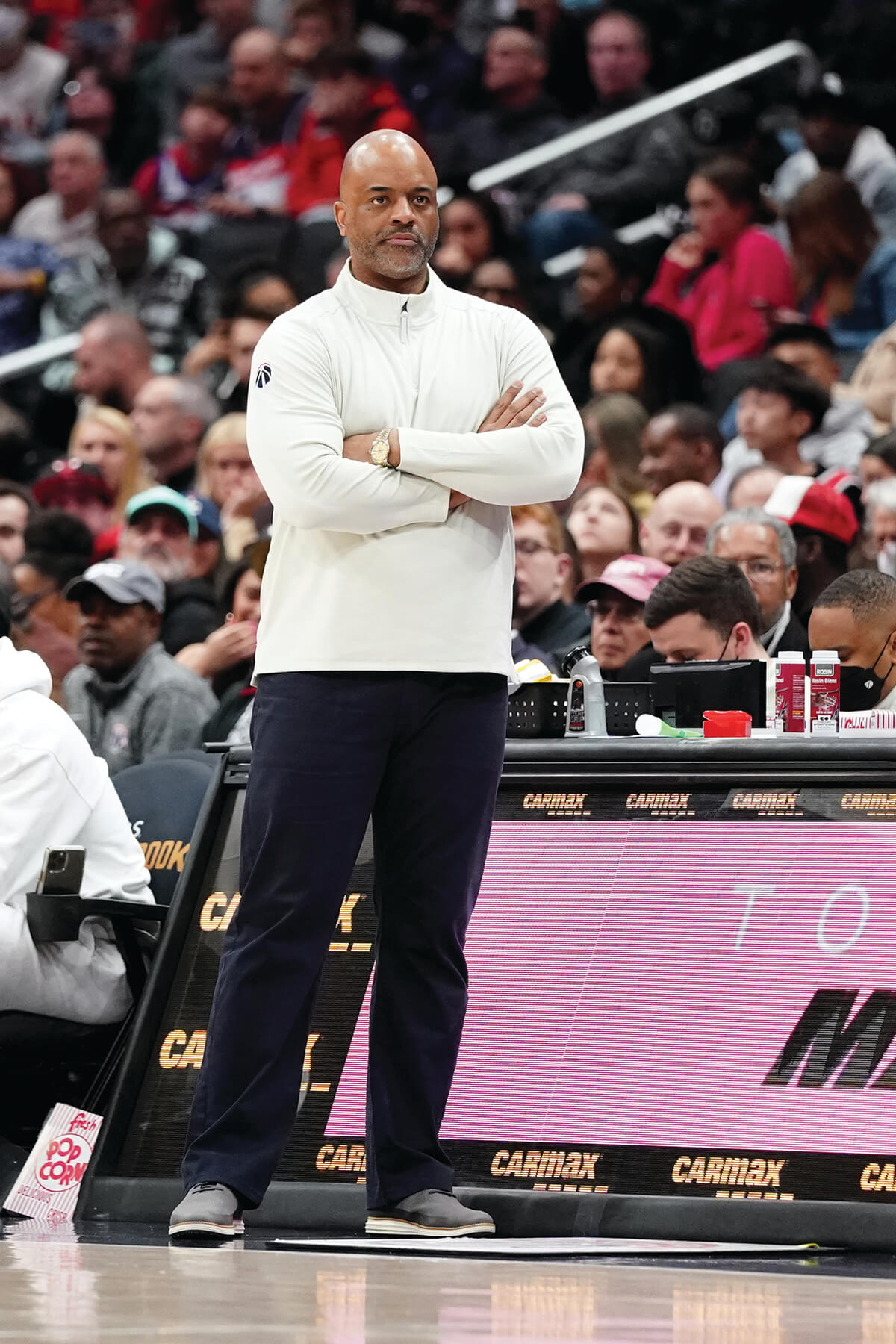

A few trinkets and mementos line the shelves behind Wes Unseld Jr.’s desk in his office at the Washington Wizards’ practice facility in Southeast D.C. One is a basketball, still in a protective plastic bag, commemorating his first win as an NBA head coach, a victory over Toronto in his debut last season. There are also two family photos, along with a posted paper copy of the team’s schedule.

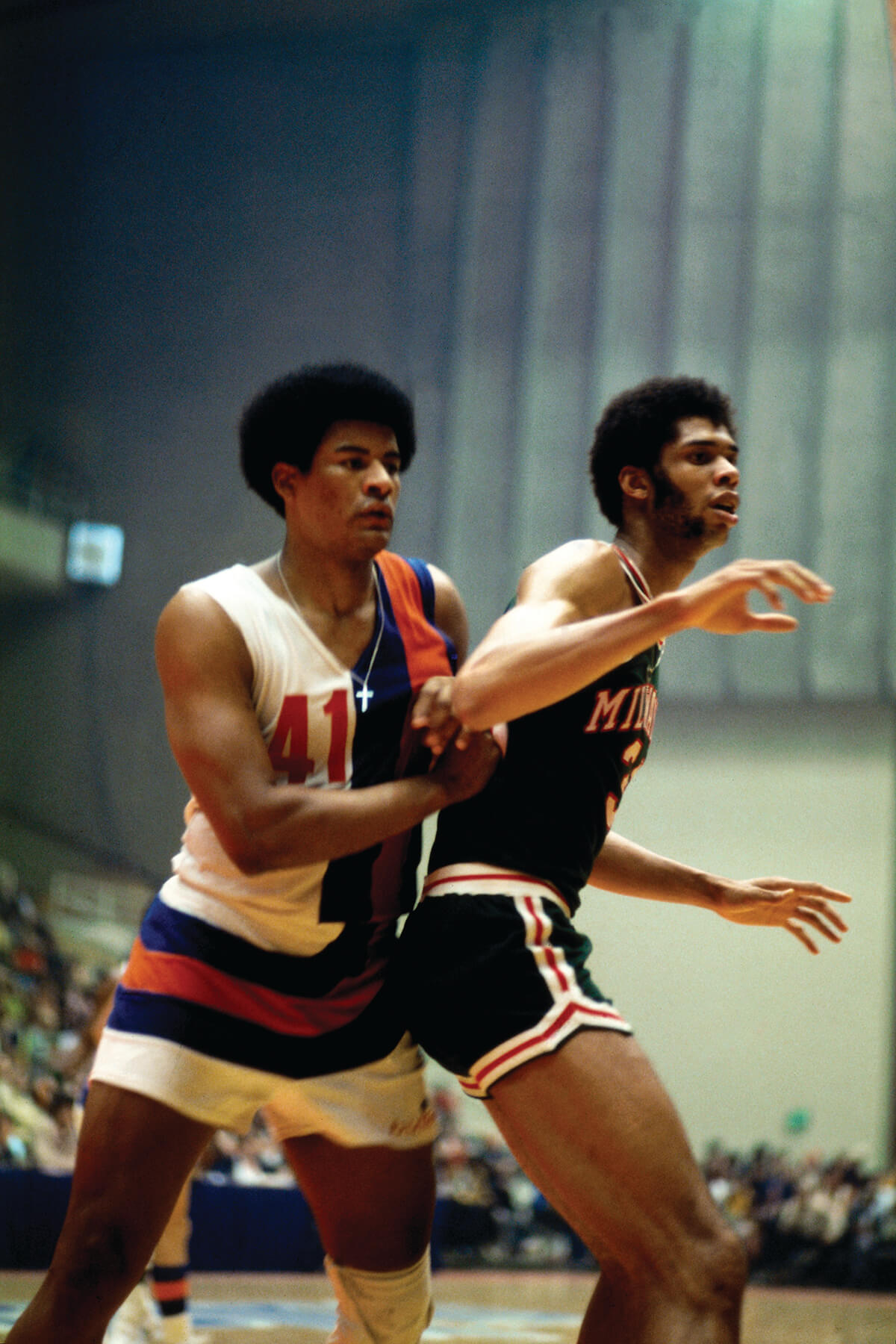

On top of a cabinet sit three bobbleheads, still in their boxes. Next to Natasha Cloud, of the WNBA’s Washington Mystics, and Manute Bol, tied for the tallest player in NBA history, is one of a broad shouldered, extremely intense-looking man squeezing a ball with two hands held high over his head. For basketball fans of a certain age, No. 41 in the red, white, and blue uniform is as an unmistakable sight.

Years after the late Wes Unseld Sr. retired from the Baltimore/Washington franchise he took to new heights, first to an NBA finals here, and then to an NBA championship after it moved south down I-95, his presence still looms large over the organization that his son was tapped to revive last year.

Following in his father’s Hall of Fame size 16+ footsteps—Wes Unseld Sr. also coached and served as general manager for the team following his retirement as player—would be no easy task for any coach, let alone one who shares his name. But perhaps there’s no one better suited temperamentally to take on that challenge—after three straight losing seasons and 44 years since the rugged, elder Unseld led them to their last title—than the cerebral, understated Unseld Jr.

“All this is surreal,” says Unseld Jr., 46, who answers questions with the thoughtfulness of a man with an economics degree from Johns Hopkins University, which he is. “I can’t believe I’m a head coach in general, but certainly not here. To know this organization inside out, growing up, and then having the opportunity to be where I’m at, back where it all started, it’s pretty cool.”

Technically, it all started 38 miles northeast from D.C.’s Capital One Arena, in Catonsville, where Wes Sr. and his wife, Connie, made their home. Unseld had come to Baltimore as the second overall pick in the 1968 draft by the NBA’s Bullets, which then played in the Civic Center downtown. A big, bruising low-post player from the University of Louisville, it didn’t take Unseld long to establish himself in the league. That year, he became only the second player in NBA history to win both the Most Valuable Player and Rookie of the Year awards in the same season. Despite their success on the court (the team made it to the 1971 NBA Finals), the Bullets left town in 1973 for a shiny new arena in Prince George’s County. The Unselds, however, decided to stay put.

“My neighbors were very warm and nurturing,” Connie says. “There was no one here in Baltimore from our family so our neighbors were a support system. They were like a second family to me. We liked Baltimore.”

It was in that same Catonsville house that they raised their daughter, Kim, and her little brother, Wes Jr.

“We had a ball,” Unseld Jr. says of growing up in Baltimore County. “It was family-friendly, lots of kids in the neighborhood. It was a pretty normal childhood of the ’80s, when you got on your bike, you tooled around. Pretty much you had the run of the neighborhood. We spent a lot of time outside, playing all kinds of sports.”

His parents never pushed their children into any particular sport or activity, Unseld Jr. says. Academics were their priority, as well as an understanding that if you started something, you could bet that you were going to finish it. Wes Jr. played the piano, sang in the choir, and liked to read. Baseball, tennis, swimming, and track and field were among his athletic pursuits, but the Unselds were a basketball family, and Wes Jr. caught the bug. From a young age he was a keen observer of the game, and often went to his father’s games at Capital Centre in Landover.

At home, the humble Unseld was cognizant of staying out of his son’s way. After retiring as a player in 1981, he went on to coach the Bullets from 1988 to 1994, but his career on the sideline had a rather inauspicious beginning, a little closer to home.

“When [Wes Jr.] was in elementary school, Wes was the coach [one] year,” Connie says. “And they lost. A lot. Wes said, ‘You played in the NBA, daddy. Why are we losing?’ I just laughed.”

Still, as Wes Jr. grew and developed as a player, his father would work with him on their court in the backyard of the family’s home.

“It was almost like watching the maestro working on mini-me,” Kim says. “My daddy never played dirty, but he would tell him it’s not a foul until the whistle blows. He’d put his body on him, and he wouldn’t let my brother anywhere near the paint.”

Unseld Jr. attended high school at Loyola Blakefield in Towson, where he developed into a solid, if not dominant player. The knock on him, as described in a 1993 story in The Sun, was that he was too unselfish.

“In a sport where one-on-one ability draws most of the attention and headlines, Loyola High’s Wes Unseld Jr. is a throwback—a basketball player who thinks team first,” it reads.

Unseld Jr., a team captain of whom his coach said, “I’ve never coached anyone who has been as much of a gentleman,” was a lowpost player who stood just 6-feet-3-inches and weighed 190 pounds, much smaller than his father. Thus, offers from big time colleges did not come flowing. Not that he cared.

“I was a very good student in high school, and I knew at an early age that I wasn’t playing in the NBA, so it was like, ‘Okay, I can still have an opportunity to play at a higher level,’” he says. “But the bigger priority was to go where you could get the best education.”

He didn’t have to go far. Unseld enrolled at Johns Hopkins, where he became a key player for the Blue Jays. A two-time captain, he helped lead JHU to 57 wins and the 1997 ECAC Championship. When he graduated in 1997, he ranked 15th in program history in scoring, and he still ranks 11th in career field goal percentage (.551) and 15th in blocks (60).

“He was smooth,” recalls his teammate and friend Evan Ellis, who’s now the Portland Trail Blazers’ orthopedic surgeon. “We called him The Classy Vet. He just moved well. I remember the first time we were playing pickup, they fed me the ball in the post, and all of a sudden he had taken it from me. I looked at him and thought, ‘Wait a minute.’ That had never happened to me before.”

At that point, coaching wasn’t on Unseld Jr.’s radar. He planned to apply to graduate schools, with an eye toward working on Wall Street. But his father convinced him to take an internship with the franchise, which had switched its name to the Wizards. A few months in, grad school didn’t stand a chance.

The nexus of the Unseld family’s universe was, and still is, Unselds’ School, a private K through 8th grade school in West Baltimore. Connie got the idea to open it after seeing the way children were educated on kibbutzes during a trip to Israel the late Washington owner Abe Pollin took her and Wes Sr. on following the Bullets’ 1978 NBA Finals’ win.

Both Connie, a kindergarten teacher, and Wes Sr., who had a degree in education, took hands-on roles at the school once it opened in 1978. Wes Sr. was much more active after his career as a player, coach, and basketball executive ended. Always a diligent worker, he cooked lunch in the cafeteria, drove a bus—whatever was necessary. Wes Jr. was the school’s first fifth-grade graduate.

“My sister and I would always laugh, [the school] was like our third sibling,” he says. “We were there all the time. Every day after school we would go there. I would go back in the library and do homework. We’d be in there cleaning up, mopping floors, taking trash out. It was a family business.”

The school took an emotional hit in 2020, when Wes Sr. died of complications from pneumonia. Unseld Jr. has been using the backing of the NBA to help with renovations. He returned to the school, one of the few fully accredited, non church-affiliated, Black-owned schools in Maryland, in April when the Wizards and Heart of America teamed up to help renovate it as part of the NBA’s 75th anniversary celebration.

“He’s very encouraging to all students who graduate,” says Connie, who remains the school’s director. (Kim is its principal.) “It’s so cool that he graduated from Unselds’ School and the most outstanding alumni is Wes Unseld. They relate to him. That’s Coach Unseld, they say, he went to my school.”

One day, when they hear about his career path, those kids will learn a valuable lesson: Regardless of his last name, Unseld Jr. had to pay his dues in the NBA. He started out scouting personnel and college games before then-Wizards assistant coach Mike Brown (now head coach of the Sacramento Kings), Unseld Jr.’s neighbor in Crofton at the time, recommended that he start scouting pro games.

“I started doing it, and I’m sure I was awful, but he was very encouraging,” says Unseld Jr., who now lives in Montgomery County with his wife, Evelyn, and their two young kids. “We watched film together. It piqued my interest. All of a sudden I was drawn into this. I fell in love with the competitive piece. Not being able to play anymore, you don’t lose that competitive spirit.”

He became an assistant coach with the Wizards in 2005, and followed that with stops in Golden State, Orlando, and Denver, where he helped develop the Nuggets’ defense and the overall game of their superstar, Nikola Jokic.

“Oh my god, I talk to Wes about anything,” the two-time MVP told The Denver Post. “He does deserve some credit. Not just defensively…He had some impact on my basketball career and my basketball growth. He’s such a great guy, he’s never gonna take credit.”

Over the past few years, Unseld Jr. interviewed for four head coaching vacancies. After each failed interview, he essentially self-scouted, asking executives how he could improve and plotting ways to better prepare. When the Wizards opportunity came up last year, he was ready. So was the rest of the NBA world. Reportedly, Jokic and Denver head coach Michael Malone called Washington executives to lobby on Unseld Jr.’s behalf.

“Extremely bright. Great communicator. No ego. Hard worker.” That’s how Malone described Unseld Jr. to The Washington Post. “Shaking hands, kissing babies, trying to get ahead, that’s one thing he’s not,” he said. “Unfortunately, I feel that’s part of the reason it took so long for him to get a head job, because he wasn’t doing those things. He was more worried about the task at hand.”

Unseld Jr. was at his mother’s house in Westminster when he got the call. Immediately, both of their minds imagined how Wes Sr., who had died 13 months earlier, would have taken the news.

“He would probably chuckle at it,” Unseld Jr. says. “He got wrapped into coaching begrudgingly. He didn’t necessarily want to coach. I think it frustrated him at times. I always knew it’s not as easy as it looks. Being around a lot of coaches, picking their brains, there’s no handbook for it. Every season’s going to be different.”

Nothing demonstrated that more than last year, Unseld Jr.’s first. After getting that victory in Toronto, the Wizards won nine of their next 12. They were the talk of the league.

Then, reality set in. Injuries, COVID-19, and reported locker room squabbling led to a slide that resulted in a major mid-season trade. Fans in Washington and Baltimore, a basketball-loving city where for many the Wizards remain the next best thing to a hometown team, were resigned to another season of mediocrity. That 1978 title, the one anchored by Wes Sr., is the franchise’s one and only. Still, there’s no doubt that the son knows what the father always preached: Nothing comes easy. That’s why many believe his even-keeled, analytical approach seems well fit for this challenging, semi-rebuilding coaching job.

“Wes is very consistent and dependable—that’s the feel that you get from him,” says Cleveland Cavaliers head coach J.B. Bickerstaff, a lifelong friend. “You always know if you [look] over your shoulder where Wes is going to be. I think that helps build a lot of trust. Because our game can be so emotional, a head coach having the poise that he does translates to his players. Now his players don’t get rattled because they know Wes is over there under control. He gets people to buy in because he is so dependable.”

Twelve-hour days in the office are the norm for him in the so-called off-season. He’s mapping out plans for players and staff, preparing for the NBA Draft and summer league, and starting to think about training camp and a preseason trip to Tokyo later this month.

There’s not much time for vacations, although he is looking forward to a coming dinner date with his mother in Little Italy. The plan is to eat at Sabatino’s, a restaurant the family has loved since Wes Sr. first came to the city. While it won’t be a home-cooked meal, it will be the next best thing: a great meal in his hometown.