Travel & Outdoors

Fair Hill is a Hidden-Gem State Park Brimming with Pastoral Beauty

An hour from Baltimore, the landscape is an evocative quilt of forest and field—part Andrew Wyeth painting, part medieval fox hunt, a sort of travel back in time.

A few days after Christmas in 2022, my husband and I went hiking in one of our new favorite places. We’d found the state-run, fittingly named Fair Hill Natural Resources Management Area, aka NRMA, after burning a trail through our local parks throughout the pandemic. After a 45-minute trip from our home, we got out, geared up, and walked directly into a fairy tale, located just outside Elkton, Maryland, in Cecil County.

Dreamlike rolling hills of deep hardwood forests were bisected by a babbling creek and peppered with tumbledown ruins. We were totally spellbound and knew we’d be coming back again and again to explore.

On that first visit, making our way up a trail between huge beech trees, my husband saw a small object poking out of the soil. He ambled over and dug it out. Using a twig to scrape away the mud, we discovered it was a heavy brass bell—a sleigh bell, to be exact, likely dropped from a horse on a snowy day long ago. Once rinsed, it rang again. A shockingly old, rich sound. That experience and our little discovery is just so very…Fair Hill.

An hour from Baltimore, located just north of the Chesapeake Bay headwaters, south of the Pennsylvania line, and a stone’s throw from Delaware, the landscape is an evocative quilt of forest and field—part Andrew Wyeth painting, part medieval fox hunt, a sort of travel back in time.

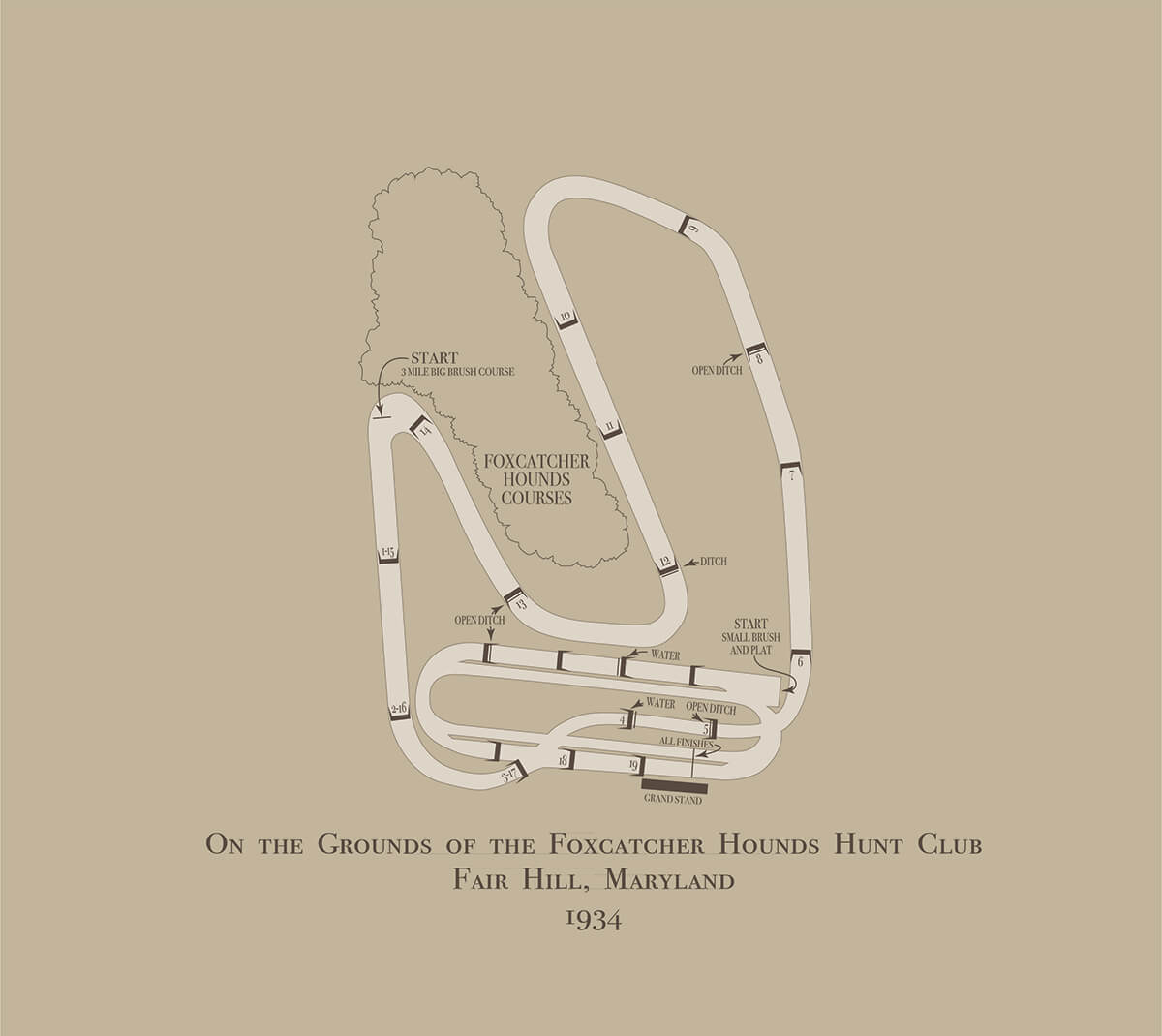

Stitched together out of hundreds of small farms during the Great Depression by prominent businessman William du Pont Jr. in the 1920s, Fair Hill was created in his vision of horse-riding splendor. Du Pont’s improvements were on a godlike scale—he completely transformed the property (more on that later)—yet the overall effect does not feel heavy-handed.

It is charming. It is accessible, now more than ever. And though Fair Hill reflects just one man’s fantasy, it manages to be enchanting for all.

From Farm to Fable

Today, Fair Hill is a vast expanse of public land—more than 5,600 acres with trails for horseback riding, biking, and hiking.

Equestrian courses abound for everything from steeplechases to dressage to cross-country events, as well as a full fairground that accommodates almost 80,000 visitors each year during events like the Maryland 5 Star horse show in October and the Cecil County Fair in July.

An old stone lodge is now home to an environmental center, where the nonprofit Fair Hill Nature Center provides immersive educational experiences for children and adults. And almost none of this—beyond the stream, of course—existed before du Pont began purchasing farm after farm to create his own utopia, with many relics from his heyday still operational today.

William du Pont Jr. was born in 1896 into one of America’s richest and most prominent families. Delaware bluebloods as savvy in business as they were in marriage, their vast holdings and estates stretched across the Mid-Atlantic. The du Ponts had a taste for 18th-century architecture and horticulture, and they used their enormous wealth to transform historic sites and landscapes—like nearby Winterthur and Longwood Gardens—into palaces of personal pleasure.

For William, a lifelong equestrian born in England and raised at James Madison’s Montpelier estate, those same tendencies ran strong. Where his relatives had poured their resources into buying up priceless antiques or cultivating entire stream valleys with rare plant specimens, his world-building was focused on his true calling—horses.

He ate and breathed thoroughbred riding, racing, and breeding, and with the help of his immense wealth, he established cutting-edge stables at his amenity-strewn estates while the rest of America was mired in the Great Depression.

Du Pont’s racing acumen was legendary in his time, and in 1937, he added a most impressive feather to his cap—his horse, Rosemont, beat the famed Seabiscuit—and then a year later, another, Dauber, won the Preakness Stakes.

At Fair Hill, du Pont’s aim was to create a personal equestrian paradise, largely for fox-hunting, a hobby he enjoyed several times a week. To achieve that goal, he needed land, and plenty of it. In the 1920s, he began buying up properties in northern Cecil County and Chester County, PA. These were not vacant lots but family farms, many settled long before the Revolutionary War, located in the heart of a once-thriving agrarian community. (After purchase, he hired some of these same folks.)

Other plots were former industrial grounds, including the sites of several water-powered flour, lumber, and textile mills along Big Elk Creek—a natural tributary of the Chesapeake that flows into the northeast Elk River.

Du Pont greatly altered this existing landscape to create a naturalistic effect. Farm fields became pastoral meadows. He bought up county roads that crossed the property—some just wagon tracks, others well-traversed byways—and either closed or improved them.

To keep deer out and fox in, he enclosed much of the property with a massive, 8,000-acre “fox-proof” perimeter fence—its concrete remnants remain today. An historic covered bridge over the clear, cold, creek waters was restored as a lovely landmark. A tumbledown stone mill was preserved as a folly.

And this work continued throughout du Pont’s lifetime, slowly tailoring the grounds to suit his needs and whims. When he could no longer ride, he widened gravel paths in order to drive a vehicle behind the hunt, and at one point, constructed a hunting lodge out of stone sourced from an on-site 18th-century farmhouse.

When du Pont got into raising and showing cattle that would even- tually be sold in Baltimore, he erected an entire fairground and built bridges to move the cows across the property. Over time, he created one of the single largest tracts of land in Maryland—then and now.

And almost everything became accessible to the public in 1975, a decade after du Pont’s death, when the state of Maryland purchased Fair Hill.

Fair Hill Today

Today, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources runs the Fair Hill NRMA, but it isn’t like any state park you’ve visited. There is no regular on-site camping, no public beaches, hardly any flushing toilets, and certainly not a shower in sight. But those amenities feel almost frivolous when du Pont’s artfully crafted natural playground is up for exploration.

In addition to those gravel paths, over 80 miles of well-maintained trails have been added throughout the vast acreage under the state’s management. With multiple entry points on either side of the sprawling grounds and a spectrum of natural environments to explore, visitors can make every visit a choose-your-own adventure.

A series of blazed trail routes—several of which intersect—allow the mix-and-match of custom routes. They follow sunny fields and hedgerows full of birdsong. They dip through wooded valleys. They tuck into rocky creek bends where mysterious ruins suggest the park’s 19th- and 20th-century history, and anglers stop for stocked put-and-take trout fishing.

And it’s not just for outdoor recreationalists—students, teachers, history buffs, and a fair share of birdwatchers visit Fair Hill year-round, from sunrise to sunset, with the sounds of cicadas providing a soundtrack in summer and snowfall creating scenic vistas in winter.

Seasons aside, you’ll likely come across solo travelers, families, folks of all ages, and a few dogs. Better yet, the trails are so extensive you might not encounter another soul.

When taking a trek, my favorite hike begins at the Appleton Road parking lot and follows the moderately strenuous green trail through stands of beeches and oaks down to Big Elk Creek, where it follows the banks before crossing the iconic red covered bridge in the heart of the park. There, I loop back north, following the difficult but short orange trail on the opposite shore, crossing again on a pedestrian-car bridge—a common spot for casting a fly rod come spring—before ultimately heading back into the woods toward the car.

Looking to throw your own line? The 60-year-old Herb’s Tackle Shop in nearby North East sells fishing licenses, rods, reels, bait, and more.

Behind the wheel, cyclists get to experience Fair Hill as du Pont intended—and the unfolding expanse of crafted environments makes sense when experienced at a swift pace.

Novice and intermediate mountain bikers will enjoy the challenging terrain and mix of paths. The red trail, which follows an old logging route, offers less technical terrain for newbies, while the yellow and green trails provide stunning scenery and a bit of a workout.

Bikers arriving from Baltimore can rent a pair of wheels with Bay Venture Outfitters in North East, with delivery and pickup available.

Meanwhile, for those who know their way around a saddle, horses are always at the heart of the Fair Hill story, and this place remains an equestrian mecca. Whatever the month, visitors can expect to share the trails with horses and riders, and on the weekends, there are almost as many horse trailers as Subarus and SUVs in the parking lots.

Visitors planning to trail ride will enjoy the blue trail, which uses a special du Pont-constructed tunnel under Appleton Road designed for the sport that follows Christina Creek. The nearby Fair Winds Farm and Stables offers trail or carriage rides in the park for those without their own Mr. Ed.

Also, plan ahead for this year’s 62nd annual Fair Hill Scottish Games, held at the fairgrounds on May 18. Games will be combined with a parade of clan tartans, Highland-style dancing, piping and drumming, and sheepdog demonstrations—need we say more?

Extend the Trip

Part of the beauty of Fair Hill is that it’s such a straight shot up I-95 from Baltimore. It’s easy to do in an afternoon, but also worth making a day or even night of it.

I love to pair a day hike with a pit stop at Valhalla Brewing Co. just down the road in Elkton for a cold beer, some nature journaling, and an array of pub food, from street tacos and wings to a personal favorite—scrapple fries. Just north across the Pennsylvania border into Lewisville, Old Stone Cider is also home to a sprawling apple orchard that uses heirloom varietals to make beautifully dry, English-style hard ciders.

For those looking to prolong their stay, the brand-new Elkton Music Hall brings a dose of energy to otherwise sleepy Elkton, drawing an impressive lineup that ranges from Baltimore talents like Cris Jacobs to national acts like Shovels & Rope. (At the end of the month, Mid-Atlantic bluegrass veterans The Seldom Scene will be taking to the stage.)

Lodging is limited mostly to bed-and-breakfasts and chain hotels, but a half hour up the bucolic backroads into Kennett Square, PA, the new Bookhouse Hotel is an adorable four-bedroom boutique inn with chic digs and, you guessed it, books in every nook.

This addition to your trip also affords the opportunity to visit Talula’s Table for scratch-made breakfast pastries and savory mushroom-strewn lunches from the region’s renowned mushroom-growing community. Not to mention the Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford with its impressive Wyeth collection, an absolute must before heading back home.

Leave No Trace

Every visit to Fair Hill offers environmental splendor on a majestic scale. Sometimes when I can’t sleep, I lie in bed and try to think of the feeling of hiking past that first line of trees and being absorbed into the woods. There is the bright red of a covered bridge or the flash of a fly fisherman casting an arc reflected in the broken currents of Big Elk Creek. The time-traveling sounds of hooves and creaking saddles add to the timeless feel.

Nowadays, my family’s Fair Hill entourage has grown by one small human, who has no choice but to love the place like his father and I do. He will grow up there, playing in the creek’s shallows, running though the long grass of the meadows, and getting a little lost along the trails through the woods. If he’s lucky, he’ll discover the small surprises that the park offers up—a man-made amphitheater of rough stone high up on a rocky creek overlook, witchy stone foundations, the shadows of paw paw trees—and his imagination will be off to the races. Just as du Pont intended, I think.

We’re often reminded as visitors to our public lands to leave no trace. But I find that with Fair Hill, the traces have been left in me instead. I hold my sleigh bell, heavy with time, and think of the hounds coursing through the woods to that ringing sound on an almost-spring day.