Arts & Culture

The ’80s and ’90s were a golden era of filmmaking in Baltimore. Can it happen again?

BY MAX WEISS

EDITED BY RON CASSIE

Illustration by Ryan Olbrysh

January 2026

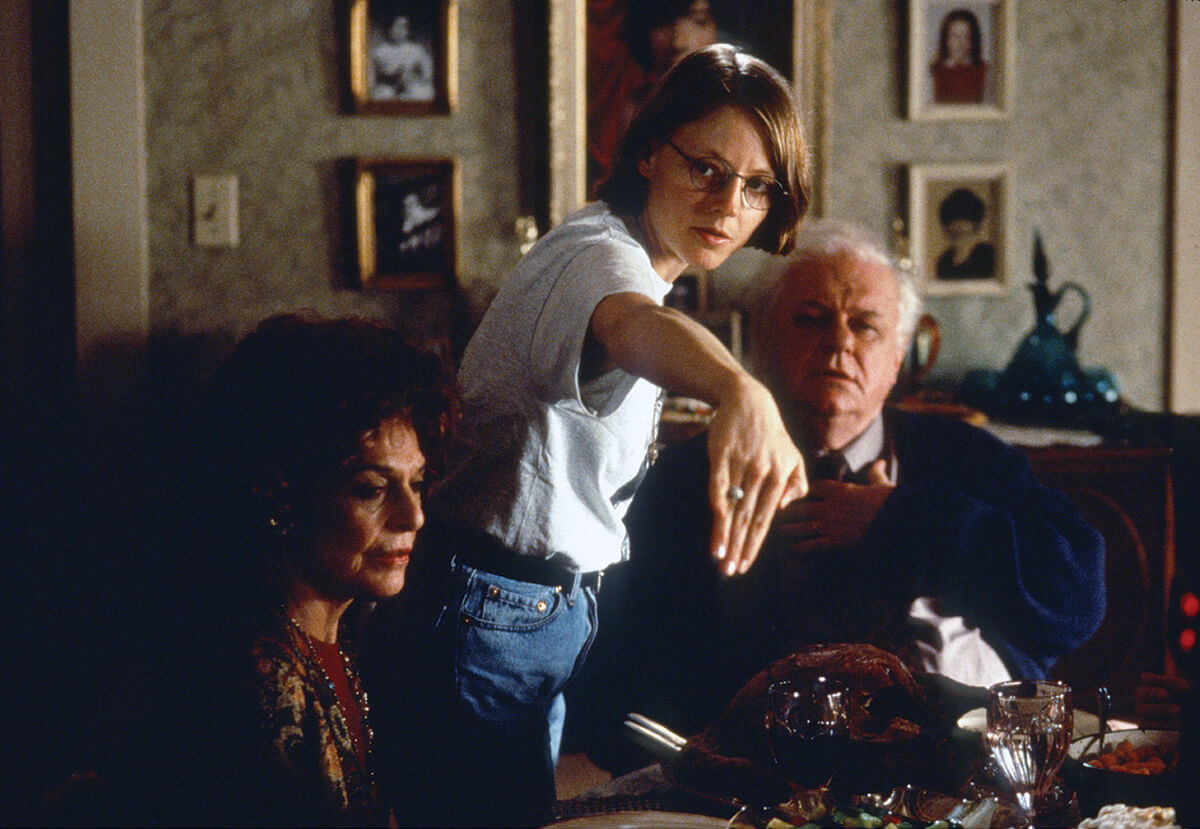

JACK GERBES, then the location and project manager of the Maryland Film Office, was driving in a van with Jodie Foster. The Academy Award-winning actress was in her director mode that day, scouting locations for her upcoming film, Home for the Holidays, that would be filmed in Baltimore and star Holly Hunter and Robert Downey Jr.

She admired the classic, American-style homes in north Baltimore and knew she wanted to use one of the exteriors for her movie.

She landed on a house with a big porch that she really liked in Homeland and sent Gerbes to inquire about its availability. He knocked on the door and an elderly man answered.

“Hi, I’m Jack Gerbes and I . . .”

“Not interested,” the man said, gruffly.

“No, I’m not selling anything,” Gerbes demurred, quickly. “I’m from the Maryland Film Office and . . .”

“We don’t want it,” the man said.

Sensing that things were going south, Gerbes motioned for Foster, who emerged from the car and joined Gerbes on the porch.

The man looked at her, blinked, then turned back toward the house:

“Honey, Jodie Foster is here.”

Such was life in the ’80s and ’90s—all the way through the early aughts—in Baltimore. Hollywood films and network television shows were shot here regularly. It wasn’t all that unusual to see film sets, with trailers and a busy crew. You might see Julia Roberts in Hampden or Al Pacino or Eddie Murphy at City Hall. Maybe you’d spot Meg Ryan in Fells Point or Kevin Bacon downtown on Charles Street. You were liable to catch mop-topped actor Steve Guttenberg literally anywhere—he appeared in no less than three Baltimoremade films (Diner, Bedroom Window, and Home for the Holidays).

Friends took the day off from work to be extras—or maybe you did—and came back with tales of how excruciatingly boring film work can be. TV stars became regulars at local coffee houses and restaurants.

Sometimes Baltimore played itself. More often, it was used as a stand-in for other cities.

“We were Paris in Washington Square,” says Debbie Dorsey, former head of the Baltimore Film Office and chair of the Maryland Film Industry Coalition (MFIC), referring to the 1997 film starring Jennifer Jason Leigh and based on the Henry James novel. “We used the Peabody library. And we were a lot of places for My One and Only, a road trip film starring Renée Zellweger. We had to be St. Louis, Boston, and several other cities for that one. We were also London in Washington Square—we filmed on Bethel Street in Fells Point—Fells Point’s a perfect London.”

That “America in Miniature” nickname proved to be prescient. Maryland really did have any terrain you needed—mountains, beaches, urban, rural—and an incredibly wide variety of architecture.

And, of course, countless times Baltimore has stood in for Washington, D.C., largely because it was cheaper and more convenient than D.C.—and way easier to get permits—and our townhouses could mimic theirs.

It was Mayor—and later Governor—William Donald Schaefer who fell for the idea of turning Baltimore into “Hollywood East” (a lofty designation that John Waters gently mocked in Cecil B. Demented). A natural showman himself, Schaefer liked the idea of mingling with stars, of making Baltimore a glamorous destination.

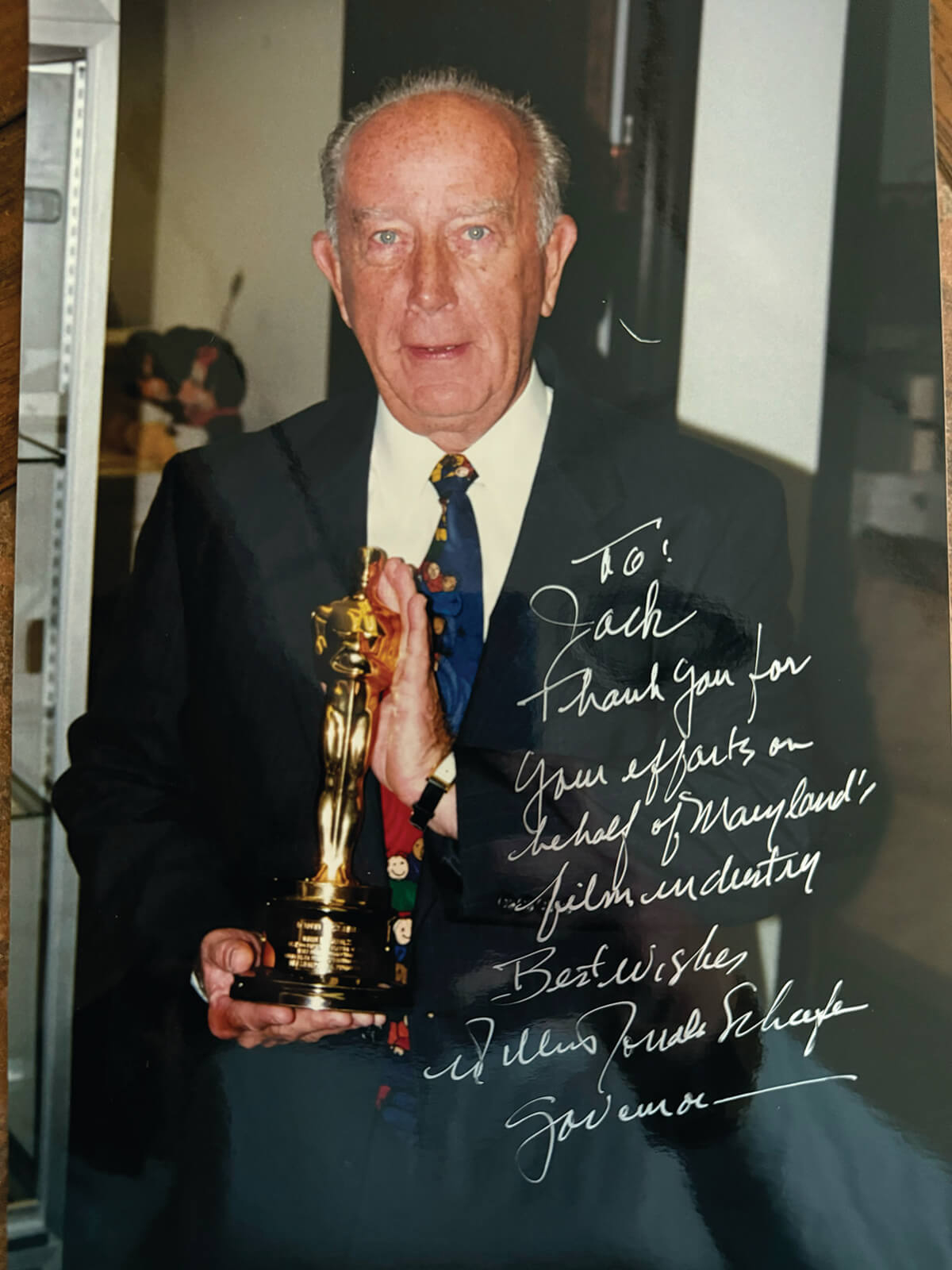

For decades, the Maryland Film Office would host an annual schmoozefest in L.A., an attempt to woo filmmakers and studios to produce their movies in Baltimore. Schaefer loved those. Jack Gerbes, who would go on to become the director of the Maryland Film Office until retiring last year, has a signed picture of Schaefer posing with an Academy Award in his office. Jed Dietz, the former director of the Maryland Film Festival, remembers Schaefer chatting up Jodie Foster at one of those parties.

“He had no idea who she was at first,” says Dietz with a chuckle. “He kept calling her ‘young lady.’” Once Schaefer found out she was looking to make a film, he laid on the charm: “If you come to Baltimore, we’ll get you whatever you need,” he said. “If you need a mountain, we’ll get you a mountain.”

ABOVE: JODIE

FOSTER DIRECTING

ANNE BANCROFT

AND CHARLES

DURNING IN 'HOME

FOR THE HOLIDAYS'; EDDIE MURPHY,

THE STAR OF THE

1992 FILM, 'THE

DISTINGUISHED

GENTLEMAN'.—FOSTER:

PARAMOUNT PICTURES/PHOTOFEST; MURPHY:BUENA VISTA PICTURES/PHOTOFEST.

ONE OF THE FIRST MAJOR FILMS to come to town was 1979’s ...And Justice for All, starring Al Pacino as a renegade lawyer fighting corruption. The film is particularly famous for Pacino’s quotable catch phrase: “You’re out of order! You’re out of order! The whole trial is out of order!” Much of it was filmed at the Baltimore courthouse. Al Pacino stayed at the Belvedere Hotel during the shoot.

Artist Harper Burke was a 17-year-old aspiring actress and a student at Bryn Mawr when ...And Justice for All came to town. She was particularly interested in the acting “method” and knew that Lee Strasberg, considered to be the father of method acting in America, was in the film. She decided to check it out for herself.

'THE DISTINGUISHED GENTLEMAN.'—EVERETT COLLECTION, INC./ALAMY

“They were filming in an assisted living center in Mt. Washington,” says Burke, now 64.

She mustered up all of her own method chops and moseyed onto the set like she belonged there.

Strasberg and Al Pacino were both in the scene, which was set in a hospital room. Strasberg’s wife, Anna, also an acting coach, was observing. Burke stood behind the camera, looking thoughtful.

Nobody stopped her.

“I was out of my mind nervous,” she laughs. But she didn’t show it. “I guess the method worked.”

She was able to chat up Anna Strasberg and ask for advice. “I’m an actress who wants to move to New York,” she said. “What should I do?” “Read. Read everything you can,” Anna replied. After the scene, Burke followed Al Pacino to his trailer, peppering him with questions about his relaxation techniques before a scene. “I saw you do a neck roll,” she said. He laughed: “There’s a lot more to it than that.” He even put his arm around her (in a paternal sort of way). Of course, like every other 17-year-old at the time, she had a major crush on him. But she did notice one disappointing thing: “He was short.”

Longtime O’s broadcaster Tom Davis also had a brush with cinematic fame on the ...And Justice for All set. He signed up to be an extra for a house party scene shot in Ruxton and was surprised when the director, Norman Jewison, asked him to stand behind the bar, directly in the frame. “I had blond hair then,” he says. “It’s white now.” His job during the scene was to eavesdrop on a conversation between Al Pacino and Jeffrey Tambor while popping a maraschino cherry in his mouth. He knew there was a chance that his scene would be cut from the film, so he was thrilled when he went to a theater and saw his own face staring back at him.

“There were 18 takes,” he says, adding he never liked the candied fruit, but was willing to suffer for his art, such as it was. “So that’s 18 maraschino cherries.”

ABOVE: AL PACINO ON THE

COURTHOUSE STEPS

IN BALTIMORE;

MICKEY ROURKE,

ELLEN BARKIN,

AND BARRY LEVINSON

BEHIND THE

SCENES OF 'DINER'. —PACINO: ©COLUMBIA PICTURES/PHOTOFEST; LEVINSON: ©MGM/PHOTOFEST.

Arts & Culture

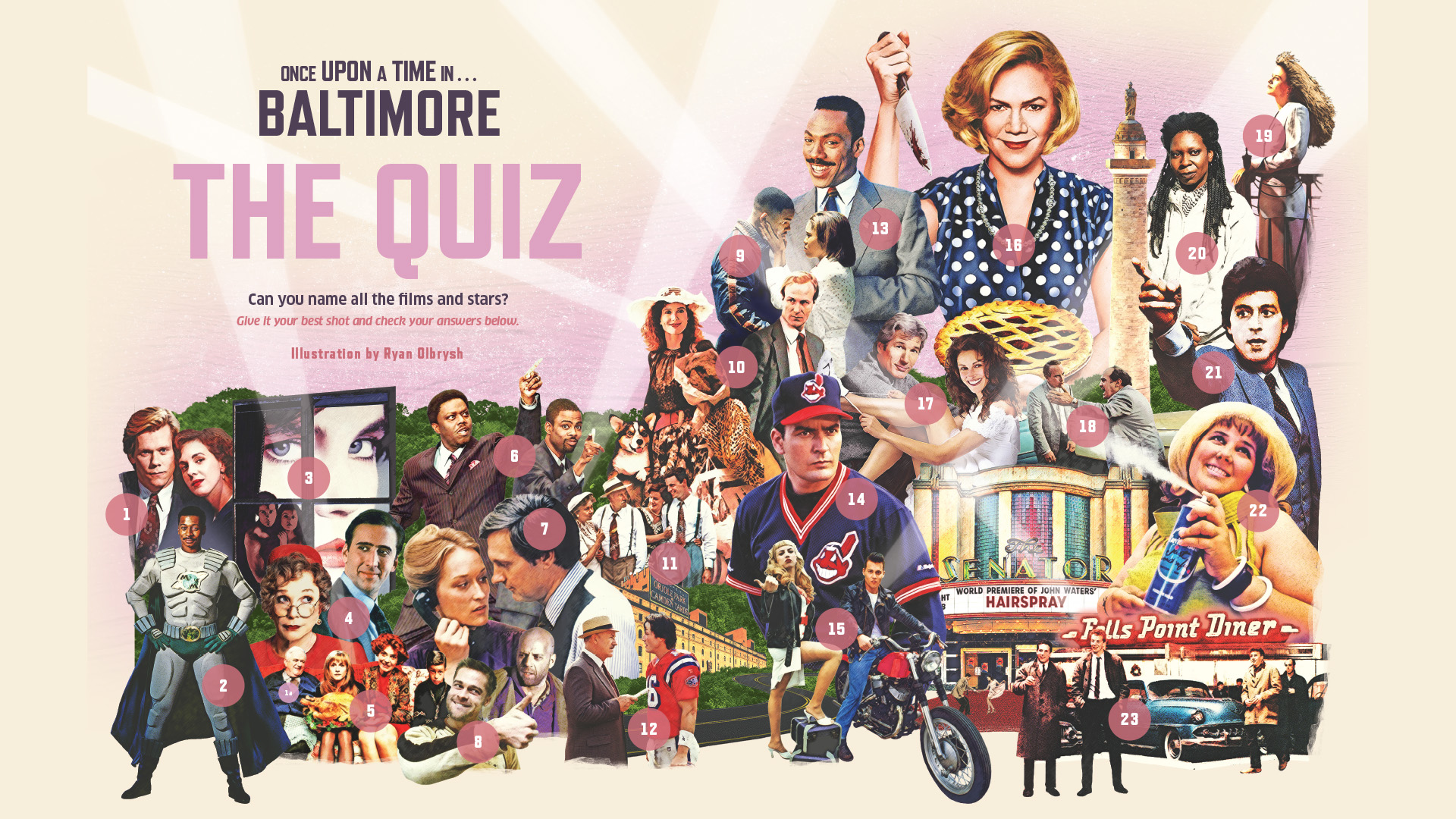

Once Upon a Time in Baltimore: The Quiz

Think you can name all the films and stars on our cover and opening spread? Give it your best shot, here.

OF COURSE, ANY DISCUSSION of Baltimore film has to begin and end with Barry Levinson and John Waters, the yin and yang of local moviemaking.

Levinson, the mensch auteur, grew up in the middle-class Jewish neighborhood Forest Park. He had an interest in comedy writing and acting so he moved to L.A. after graduating from American University in Washington, D.C.

'...AND JUSTICE FOR ALL.' —EVERETT COLLECTION, INC./ALAMY.

And he experienced success, especially as a writer, working with comedy legends—first writing for TV variety shows like The Carol Burnett Show and eventually working with Mel Brooks on the screenplays for Silent Movie and High Anxiety.

It was ...And Justice for All, which Levinson co-wrote with his then-wife Valerie Curtin, that brought him back to Baltimore. He says the concept came from discussions he had with friends here, who had become lawyers and told him, “The legal system is much more chaotic than it’s portrayed in film and television,” he recalls.

In Levinson’s mind, it just made sense to film it in Baltimore, since that’s what he knew. He asked director Jewison to scout the area, and he agreed that the city had the right stuff.

“And that’s how it happened,” Levinson says.

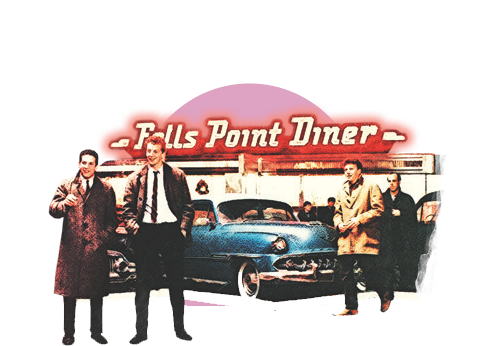

Next, of course, was the film that would change Levinson’s life, and the course of Baltimore film: Diner, about a bunch of male friends on the cusp of adulthood, who would hang out at a local diner and yap about women, the Colts, the relative talents of Frank Sinatra vs. Johnny Mathis—anything but their fears and hopes for an uncertain future. (The film used a real, albeit out-of-service diner for the shoot, which later became something of a landmark when it was relocated to Holliday and Saratoga streets and renamed the Hollywood Diner.)

A PROMOTION

FROM THE MARYLAND FILM OFFICE.—COURTESY OF JACK GERBES

Again, Levinson didn’t see himself as some sort of savior who heroically brought film production to his hometown.

“Originally MGM wanted to film it in Chicago,” he says. “And I said, no, no. That’s not right. It takes place in Baltimore. Everything I wrote about is from Baltimore. Chicago doesn’t feel like the city I know.”

So the studio caved.

The film went on to launch the careers of several young actors, including Mickey Rourke and Kevin Bacon, and earned Levinson an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay. In 2012, Vanity Fair named it the most influential film of the last 30 years.

It was the first of Levinson’s critically acclaimed Baltimore series, which focused on Baltimore life from an historical, often autobiographical lens. The others were Tin Men (1987), about dueling aluminum siding salesmen played by Richard Dreyfuss and Danny DeVito (fun fact: they were initially supposed to be Formstone salesmen but the studio thought no one outside of Baltimore would get the reference); Avalon (1990), about the Baltimore Jewish immigrant experience; and Liberty Heights (1999), another coming-of-age film set in the 1950s, focusing on race relations.

Beyond that, Levinson worked out of Hollywood, where he’d been living since graduation. His incredible run in the ’80s and ’90s as a director included The Natural, Bugsy, Wag the Dog, and Rain Man, which earned him his first Oscar.

FORMER MAYOR

WILLIAM DONALD

SCHAEFER.—COURTESY OF JACK GERBES

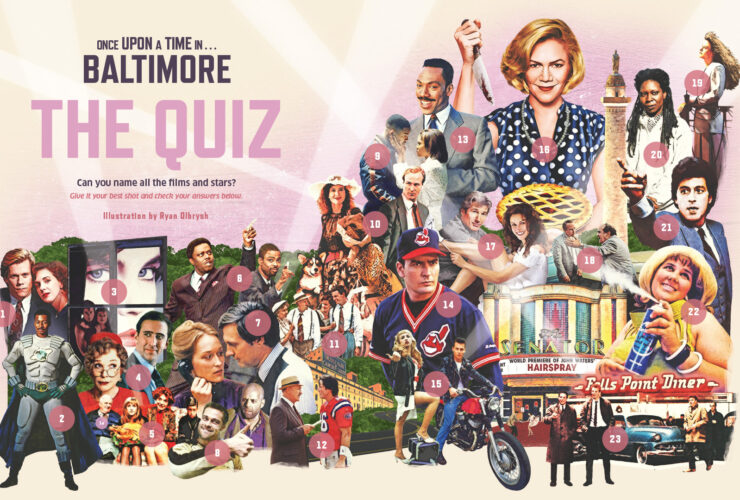

Not long after Levinson had made his way to Hollywood, a young punk named John Waters, raised Catholic and the product of, it turned out, preternaturally patient parents, started making films with a group of misfit friends, nicknamed The Dreamlanders. The films, like Multiple Maniacs, Pink Flamingos, and Female Trouble, were low-budget and intentionally outrageous, even profane—but they always had a core of sweetness because, well, Waters himself was sweet. Now that Waters has become something of a treasured elder statesman, it’s hard to remember that he once was considered a pariah to some of Baltimore’s most decorous people, an example of everything wrong with kids these days. (Waters, true to form, relished the characterization.) For years, his films were scruffy, DIY affairs—sometimes filmed at his parents’ Lutherville house, turning their backyard into his backlot. But the budgets kept getting bigger and bigger—and eventually he was filming on soundstages and locations with large crews. He finally broke through to a mainstream audience with Hairspray, now considered a family classic. (Sorry, John.)

DIVINE

(GLENN MILSTEAD)

AND JERRY STILLER

ON THE SET OF

'HAIRSPRAY'. —PICTURELUX/THE HOLLYWOOD ARCHIVE/ALAMY.

BY THE EARLY ’80S, Baltimore had acquired a reputation for being accommodating to film crews—helping with permits and location scouting and with plenty of experienced and willing crew members in town. More movies were filmed or partially filmed here—Accidental Tourist (based on Anne Tyler’s acclaimed novel), Her Alibi, Men Don’t Leave, Bedroom Window, Major League II, Runaway Bride, and the list goes on. Movie website IMDb lists 69 films that were at least partially shot in Baltimore between the years 1979 and 2000.

'THE BEDROOM WINDOW.' —ALBUM/ALAMY.

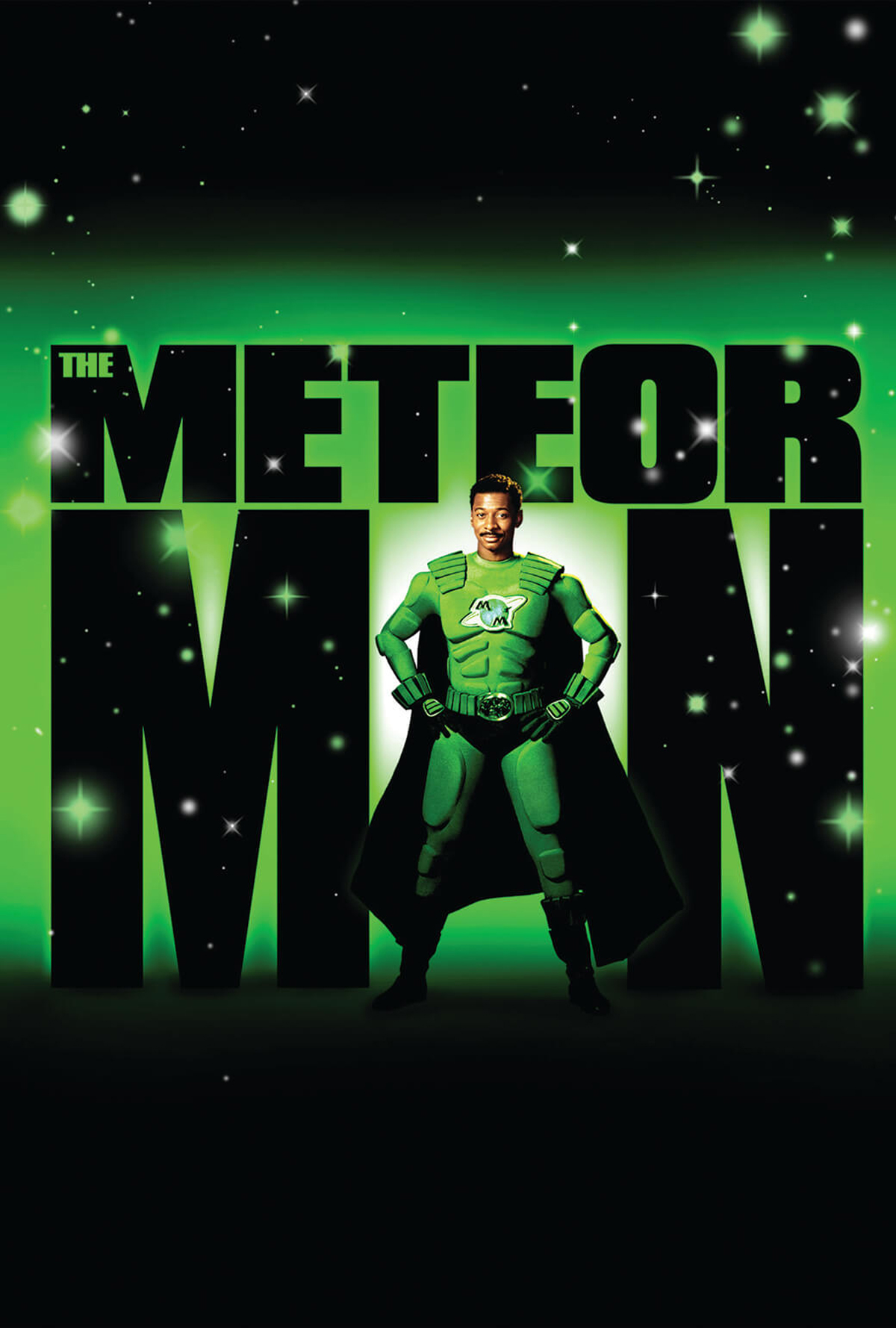

Emmy-nominated Baltimore makeup artist Debi Young, who has worked on films such as Shirley, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, Fences, and Jackie, got her start in film on the 1993 superhero comedy The Meteor Man, whose ensemble cast included writer-director-actor Robert Townsend, James Earl Jones, Bill Cosby, Luther Vandross, Sinbad, Marla Gibbs, and Robert Guillaume.

“My friends Janice Kinigopoulos and Lydia Benaim worked in the hair department, and we just talked about this recently, it was six days a week,” says Young with a laugh. “Six nights week, I should say, because the entire movie was shot at night, except for maybe three days shooting. But we were so excited to be there, we didn’t even want to go home. We loved it so much.”

Townsend, she continues, wanted to shoot in Black neighborhoods and among other locations, filmed in Reservoir Hill, making sure even the extras were taken care of, receiving hot meals each day. Naturally, the whole community came out to see the stars.

“I remember one local little girl whose birthday fell during the shooting,” recalls Young, whose Baltimore-associated credits include The Wire, Homicide, and Serial Mom, among many others. “She lived in the neighborhood and Robert [Towsend] found out it was her birthday and he gave her $50. I remember that child running over saying, ‘Mr. Robert is rich! He just gave me $50 for my birthday!’”

Not quite everything went as planned, notes Lashelle Bynum, a Baltimore Heritage board member who interviewed Lenny Clay, the former owner of Lenny’s House of Naturals, about The Meteor Man shoot.

“They had started to film in his shop, which was famous for cutting the hair of Earl ‘the Pearl’ Monroe, all kinds of politicians and TV personalities of the day,” Bynum says, shaking her head and smiling. “And then they broke his ceiling with their equipment and he put them right out. That was the end of that. Oh, Lenny was a character himself. Later, Homicide wanted to use his shop as a location and he told them, ‘Hell no.’”

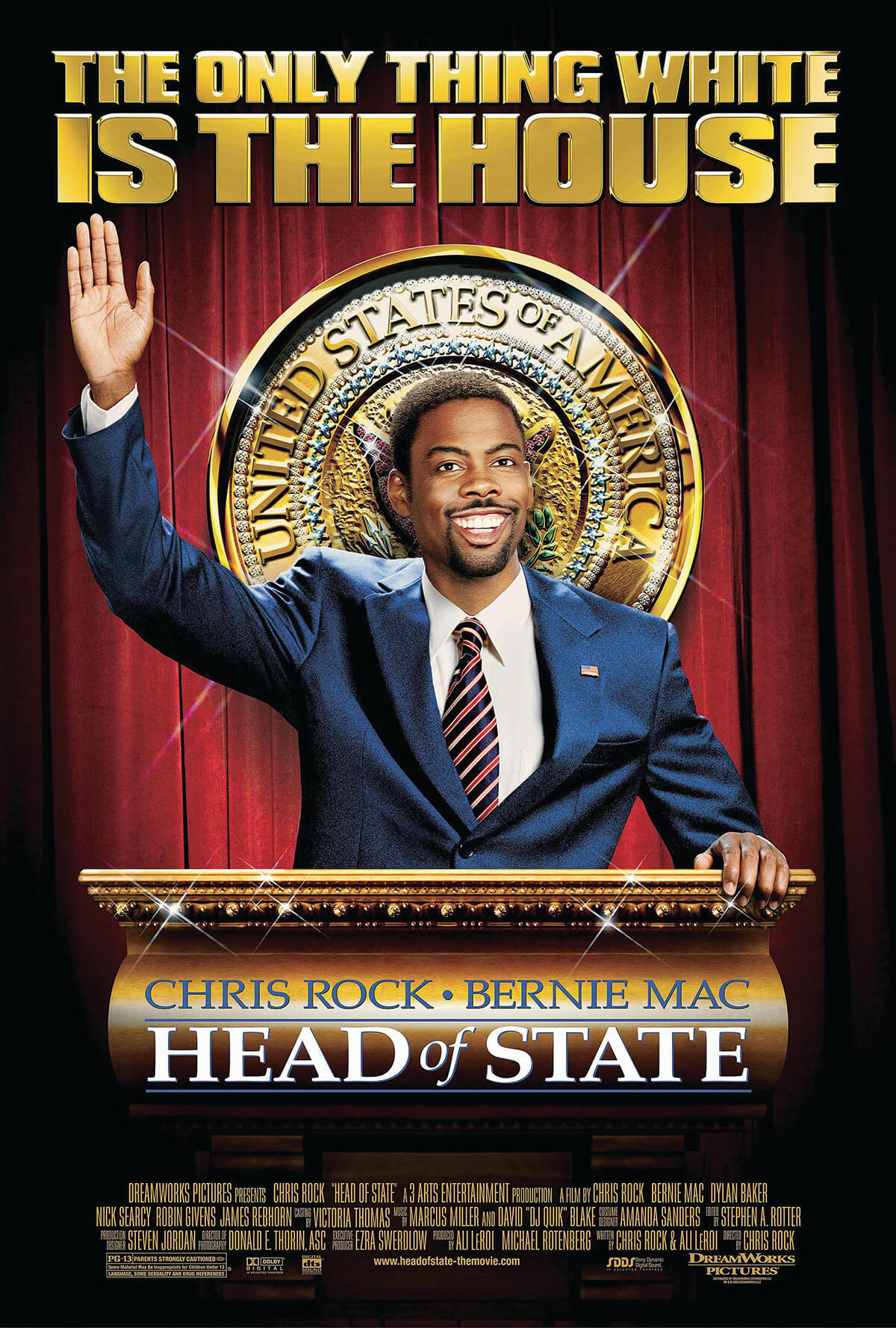

Young also has fond memories of working on the Chris Rock/Bernie Mac 2003 film, Head of State, shot in Baltimore.

“Chris Rock played his younger brother, and they were so funny together,” Young says. “Tracy Morgan was in that, too. People loved it when we were shooting on the street or at Penn Station, especially. Fans would want to walk up and ask for autographs, and if they weren’t busy right at that moment, if it didn’t affect their work, they were gracious.”

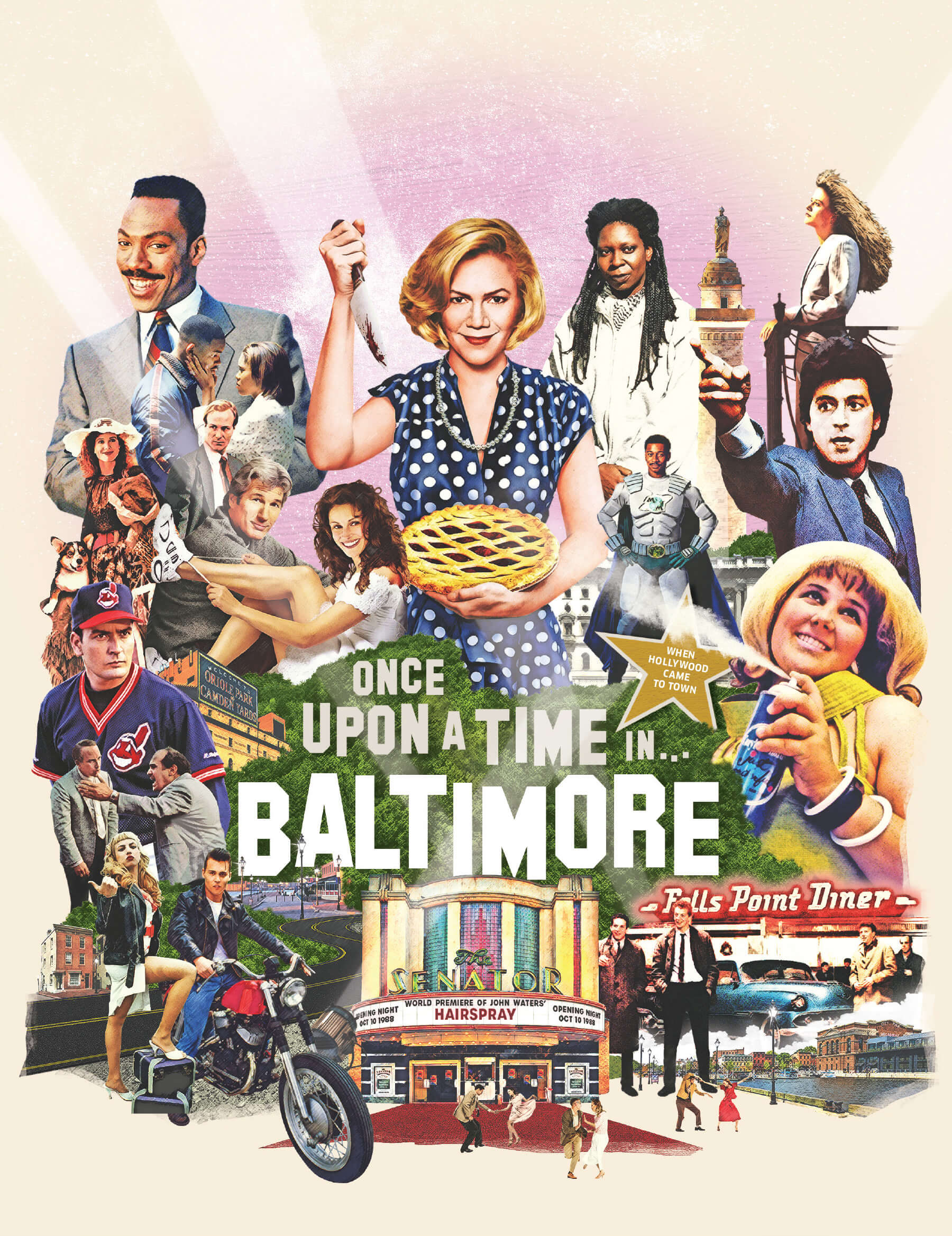

But by 2005 or so that film work had largely dried up. Specialized crew members who had been able to make a living in town—gaffers, grips, camera operators, and the like—were forced to chase jobs out of state. The phones rang a lot less often at the Maryland and Baltimore film offices. A few productions still came, but it was more of a drip-drip-drip than a steady flow.

So, what caused this? There were many factors—a shifting film landscape, for one, as studios produced fewer movies, moving away from mid-budget films to megabudget Marvel and DC Comics tentpoles; the introduction and rise of streaming television; a declining audience for theatrical film—but mostly it had to do with money.

“A lot of films were going to Canada and other countries because the exchange rate was better and the labor was cheaper,” says Debbie Dorsey, who stepped down from her role as director of the Baltimore Film Office after BOPA temporarily lost its contract with the city. (BOPA has since rebranded as Create Baltimore.)

And those films that were made in the U.S.? Increasingly, they went to cities that offered better “incentives,” like Georgia, Illinois, and Massachusetts, which have no cap on the amount of tax credits a film can receive. (There’s a reason why that “Made in Georgia” jingle is probably stuck in your head.) By comparison, Maryland has a $12-million annual cap.

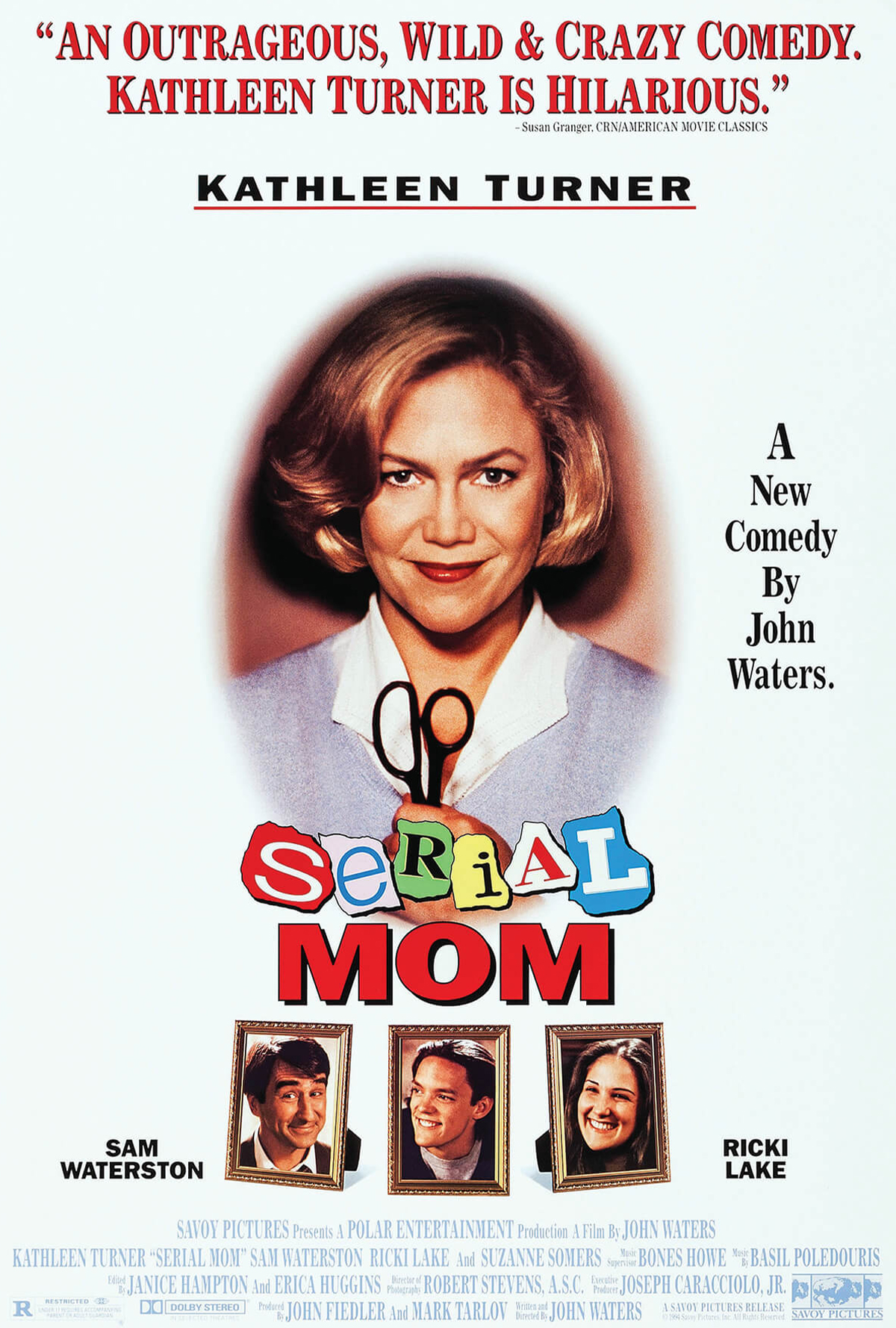

'SERIAL MOM.' —EVERETT COLLECTION, INC./ALAMY

Levinson, for his part, remained steadfast, long championing more film production in Baltimore—which he says can be an economic boom. In 2009, he even went to Annapolis to advocate for an updated film incentive program.

“I’ll never forget an article I read in the 1980s. The premise was that Hollywood studios are picking the pockets of people in Maryland,” says Levinson, still bristling at the memory. “The writer got it all wrong, because, in fact, the economics are very beneficial to the state. You have a whole crew coming in; that’s a lot of people. We’re hiring local people, too. We’re spending money on things like food, gasoline, hotels. Often, we’re renting properties. Georgia right now is making not thousands but millions.”

DIRECTOR

JOHN WATERS,

SEATED BETWEEN

SAM WATERSTON

AND KATHLEEN

TURNER, ON THE

SET OF HIS 1994

BLACK COMEDY,

'SERIAL MOM.' —©SAVOY PICTURES/PHOTOFEST

And, of course, when the right film hits, it can drive tourism to the region, not to mention boost civic pride. Which leads us to The Wire.

Baltimore has had an uneasy relationship with the David Simon oeuvre set and filmed here—including Homicide: Life on the Street (which Levinson produced), The Corner, The Wire, and We Own This City. All were excellent works of art—indeed, in many a critical circle The Wire is considered to be the best television series of all time. But they painted a dark picture of a city that was riddled with crime and drug abuse. The other big shows filmed in Baltimore— House of Cards and Veep—weren’t set in Baltimore, so they had no reputational value (and Veep’s production moved to Los Angeles for its final three seasons when they received better tax credits from California). To this day, Baltimore is mostly known by out-of-towners as the city of The Wire. (Levinson, for his part, was a fan of The Wire, thought it was “good for Baltimore,” and doesn’t understand why anyone would think otherwise.)

'THE METEOR MAN.' —©MGM/PHOTOFEST

Then came a series of unfortunate events: the pandemic and the writer’s strike, the retiring of Gerbes, the dissolution of the Baltimore Film Office—none of which improved Maryland’s already anemic filmmaking landscape.

But in 2025, there was one particularly bright light: Jay Duplass’ The Baltimorons, a love letter to Baltimore co-written by and starring Michael Strassner, a Baltimore native with deep ties to his hometown.

The film was made on a shoestring budget and greatly aided by the connections that Strassner and producer David Bonnett, also from Baltimore, were able to tap into.

“It was a lot of, who has a house we can use? Whose car would look good in this scene?” recalls Bonnett. When they needed a dentist’s office for the film, they went to Strassner’s real childhood dentist, who leaped at the chance. (Never before has a dentist’s office received such a raucous round of applause at a screening—the dentist and his staff were invited to the film’s local premiere at The Senator Theatre.)

ABOVE:ROBERT

TOWNSEND, WRITER,

DIRECTOR, AND

STAR OF THE 1993

FILM, 'THE METEOR

MAN', SHOOTING

ON LOCATION IN

WEST BALTIMORE; CHRIS ROCK

AND BERNIE MAC,

WHO CO-STARRED

AS BROTHERS IN

THE 2003 POLITICAL

COMEDY 'HEAD OF

STATE', WHICH WAS

SHOT ON LOCATION

IN BALTIMORE. —THE METEOR MAN:©MGM/PHOTOFEST & CINEMATIC/ALAMY;ROCK/MAC: PHOTOFEST.

As Strassner told Baltimore in August: “The city is filled with so many people who are willing to help. I had so many extras that were my family and friends. People just took time out to help and it was the most beautiful thing. Places like Rocket to Venus and Dylan’s [Oyster Cellar]. We were like, ‘Can we use these locations?’ And they were like, ‘Of course!’”

'HEAD OF STATE'. —AJ PICS/ALAMY.

Bonnett and his friend Jonathan Bregel, another Baltimore native who was the cinematographer for The Baltimorons, recently went to a networking event thrown by Baltimore Homecoming, an organization devoted to reconnecting notable Baltimore alumni with their hometown. They made their pitch about making films in Baltimore to a well-heeled crowd who received them with unexpected enthusiasm.

“People just wanted to give us money,” Bregel says with a chuckle.

“I hadn’t had that many people come up to me in a while,” says Bonnett. “I’ve been booked with meetings and Zoom calls since. But it’s still in the conversation stage.”

Nonetheless, Bregel remains optimistic. “The next golden age [of local cinema] won’t necessarily be about a few breakout names. It’s more about building an ecosystem where more [film] voices can thrive.”

Albert Birney, the micro-budget director of such indie darlings as Sylvio, Strawberry Mansion, and his latest, OBEX, says it’s possible to make a film for $11 grand, which was his budget for OBEX.

“People are shocked when you tell them that,” says Birney. “They have it in their heads that you need a lot of money to make a movie. And sure, that’s true of some types of movies, but there’s always other ways, you know.”

Small, largely self-funded indie films, like Matt Porterfield’s Putty Hill and Hamilton or Angel Kristi Williams’ Really Love, are not going away and are very much in keeping with Baltimore’s resilient, do-it-yourself DNA.

And if someone handed Birney $5 million to make a film?

“Honestly, if someone gave me that check with no strings attached, I think I would talk to my friends and see how much they needed to do films cheaply this way, too,” he says. “It would be like, how many movies can we get out of this? And maybe I would take one million of it myself, because that would be more than I’ve ever had.”

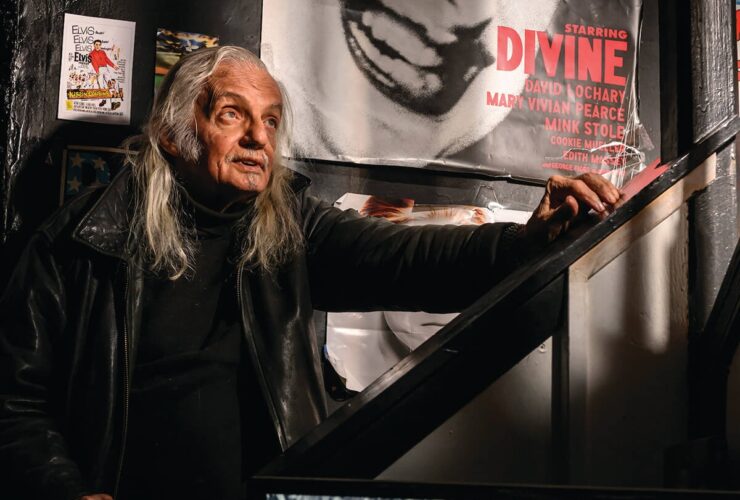

TWENTY OF MANY

A few years after Baltimore’s original 1974 Charm City marketing campaign, Mayor William Donald Schaefer pivoted to Hollywood to rebrand Baltimore as a cultural hub. Why not? It’s a glamorous business and movies can be delightful. And the careers of native sons Johns Waters and Barry Levinson were taking off. During an era spanning the 1980s and 1990s (with spillover), the big studios shot a lot of movies here and, believe it or not, spotting a Richard Gere and Julia Roberts in Hampden, while always fun, wasn’t all that unusual. Here are some of the better-known films shot here. —Ron Cassie

...And Justice for All

1979

Starring Al Pacino, Jack Warden, John Forsythe. Co-written by Valerie Curtin and Barry Levinson. Plot: A passionate Baltimore defense attorney is forced to represent a corrupt judge, while also battling the legal system to defend the innocent.

Critics’ Rating:

Diner

1982

Written and directed by Barry Levinson. Starring Steve Guttenberg, Daniel Stern, Mickey Rourke, Kevin Bacon, Timothy Daly, Ellen Barkin. Plot: A group of buddies in late 1950s Baltimore struggle with the transition into the responsibilities of adulthood.

Critics’ Rating:

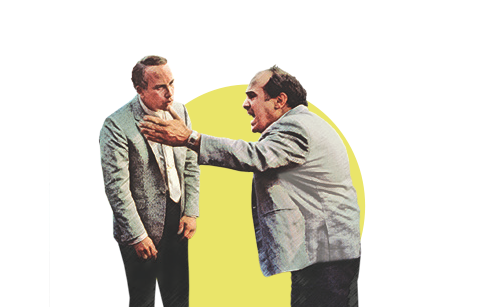

Tin Men

1987

Written and directed by Barry Levinson. Starring Richard Dreyfuss, Danny DeVito, Barbara Hershey. Plot: Rival, door-to-door aluminumsiding salesmen battle life, themselves, and each other in early 1960s Baltimore.

Critics’ Rating:

The Accidental Tourist

1988

Based on Baltimore author Anne Tyler’s novel by the same name. Starring William Hurt, Kathleen Turner, Geena Davis. Plot: A grieving Baltimore travel guide writer struggles to move forward after his son is killed and the tragedy causes his marriage to crumble.

Critics’ Rating:

Clara’s Heart

1988

Starring Whoopi Goldberg, Michael Ontkean, Kathleen Quinlan, Neil Patrick Harris. Plot: A well-to-do Baltimore family, suffering the loss of a child, hires a grounded housekeeper they’d met in Jamaica.

Critics’ Rating:

Hairspray

1988

Written and directed by John Waters. Starring Ricki Lake, Sonny Bono, Ruth Brown, Divine, Jerry Stiller, Debbie Harry, Mink Stole. Plot: A teenager lands on a local TV dance show and advocates for integration.

Critics’ Rating:

Avalon

1990

Written and directed by Barry Levinson. Starring Armin Mueller-Stahl, Elizabeth Perkins, Joan Plowright, Aidan Quinn. Plot: A Polish-Jewish family builds a new life in Baltimore in the early and mid-20th century.

Critics’ Rating:

Cry-Baby

1990

Written and directed by John Waters. Starring Johnny Deep, Amy Locane, Susan Tyrrell, Ricki Lake, Traci Lords, Polly Bergen. Plot: A teenage rebel with a heart of gold wins the love of a good girl, causing a scandal.

Critics’ Rating:

He Said, She Said

1991

Starring Kevin Bacon, Elizabeth Perkins, Sharon Stone. Plot: Two rival Baltimore Sun journalists become co-hosts of a morning news show and a romanticcomedy drama ensues from their different perspectives.

Critics’ Rating:

The Distinguished Gentleman

1992

Starring Eddie Murphy, Lane Smith, Sheryl Lee Ralph, Joe Don Baker, Victoria Rowell, Charles Dutton. Plot: A con man believes becoming a U.S. congressman is a ticket to fast money, but then he develops a conscience.

Critics’ Rating:

The Meteor Man

1993

Starring Robert Townsend, Marla Gibbs, Eddie Griffin, Robert Guillaume, James Earl Jones, Bill Cosby, Luther Vandross. Plot: A teacher working in an urban environment discovers, after being hit by a falling meteor, that he has new superpowers.

Critics’ Rating:

Sleepless in Seattle

1993

Starring Meg Ryan, Tom Hanks. Plot: A recently widowed Seattle man’s son calls a syndicated radio talk show to help find his dad find a new companion. A Baltimore Sun reporter, who is engaged, believes she might be his soulmate.

Critics’ Rating:

Serial Mom

1994

Written and directed by John Waters; Starring Kathleen Turner, Sam Waterston, Ricki Lake, Suzanne Somers. Plot: A picture-perfect suburban mother and homemaker will literally commit murder over the slightest offenses to keep her children content.

Critics’ Rating:

Guarding Tess

1994

Starring Shirley MacLaine, Nicolas Cage, Richard Griffiths. Plot: A dedicated Secret Service agent gets assigned to protect an eccentric former first lady, but he thinks the job is beneath him until she and her driver are kidnapped.

Critics’ Rating:

Major League II

1994

Starring Charlie Sheen, Tom Berenger, Corbin Bernsen, Omar Epps, Dennis Haysbert, Bob Uecker. Plot: After winning the division title the previous season, success appears to have ruined the infighting Cleveland Indians, who get off to a slow start before a late-season rally.

Critics’ Rating:

12 Monkeys

1995

Starring Bruce Willis, Madeleine Stowe, Brad Pitt, Christopher Plummer. Plot: In a future where most of humanity has been wiped out by disease, a convict living in an underground compound is sent back in time to learn about the man-made killer virus.

Critics’ Rating:

Enemy of the State

1998

Starring Will Smith, Gene Hackman, Jon Voight, Lisa Bonet, Regina King. Plot: A U.S. congressman is assassinated after opposing a counter-terrorism bill in a financially motivated crime that eventually entangles an honest labor lawyer.

Critics’ Rating:

Runaway Bride

1999

Starring Julie Roberts, Richard Gere, Joan Cusack, Héctor Elizondo, Rita Wilson. Plot: A New York columnist writes about a woman who has left three fiancés standing at the altar. However, he gets the details wrong and goes to meet the woman himself.

Critics’ Rating:

The Replacements

2000

Starring Keanu Reeves, Gene Hackman, Orlando Jones, Jon Favreau. Plot: During a pro football strike with four games left in the season, team owners hire substitute players, including a washed-up former college quarterback who lives on a houseboat.

Critics’ Rating:

Head of State

2003

Starring Chris Rock, Bernie Mac, Dylan Baker, Robin Givens, Lynn Whitfield. Plot: After the Democratic Party presidential and vicepresidential nominees die in a plane crash, a likable D.C. alderman is picked as the replacement.