Arts & Culture

Role Models

We profile some of our city's most beloved icons.

In the 1960s, New York had counterculture artist Andy Warhol with his “Factory,” where beautiful people of all stripes came together to party, do drugs, have sex, and make art. In the ’70s, Baltimore had John Waters and his “Dreamlanders,” a ragtag group of outsiders, weirdos, and misfits who comprised the cast and crew of his subversive films. (And perhaps had sex and did drugs—hey, that’s their business.)

It feels fitting to compare the two (and Waters has acknowledged that Warhol was a huge influence), especially when it comes to their respective cities. While both worked in the realm of camp, Warhol wanted to explore, deconstruct, and exploit beauty. Conversely, Waters wanted to create a new version of beauty. His glamour was anti-glamour; his aesthetic was, essentially, so-ugly-it’s-beautiful.

You could make the case that he has been the perfect Baltimore filmmaker—an artist who embraced the city’s underdog qualities, its rough edges, its working-class bona fides, and—most importantly—its sense of humor about itself.

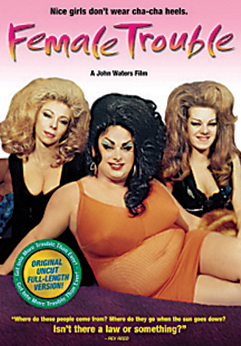

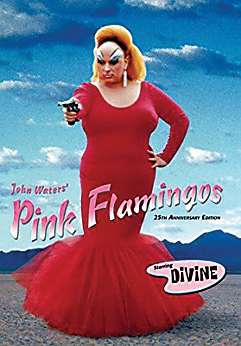

After all these years, it’s important to remember what a rebel Waters was in the early days. His films were designed to discomfit and shock; he wanted to eat the rich and take down the bourgeoisie. He famously scuffled with Maryland’s draconian censor board, and his movies were banned in several countries. In Baltimore, he was initially embraced only by arthouse fanatics and punks, but eventually—first with Pink Flamingos, then Polyester, and ultimately with his breakthrough hit, Hairspray—he was embraced by the mainstream.

Hairspray has become something of a cottage industry, but the original film shouldn’t be confused with the more mild-mannered (if still delightful) versions that followed. Waters’ Hairspray was a wonderful celebration of diversity and a takedown of racism, but it also had a scuzziness around the edges that the subsequent iterations lacked. (It also featured a touching and widely acclaimed performance by Waters’ dear friend the drag queen Divine, who tragically died shortly after the film debuted.)

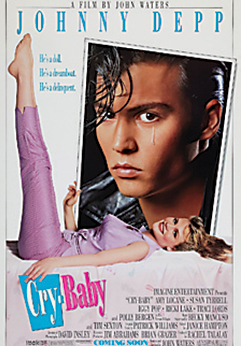

By the time Cry Baby came around, Baltimore had already begun to commodify the kitsch of his films—selling pink flamingo lawn figurines and hairspray cans in his honor. Somehow, the notion of the “Hon”—so integral to Baltimore’s Charm City concept—became wrapped up in the Waters iconography. But in a 2008 article in USA Today, Waters swore off the word and even the Honfest. “To me, it’s used up,” he said. “The people that celebrate it are not from it. I feel that in some weird way they’re looking slightly down on it. I only celebrate something I can look up to.”

This is the most crucial aspect of Waters’ art. If you think he’s making fun of the Edie the Egg Lady, you’re missing the point. He loves these people, and he respects them, too. The world of John Waters is all-inclusive. The only people he judges are those who judge others. What could be more Baltimore than that?

WONDER WOMEN

If Baltimore were on the big screen, it would star a cast of leading ladies.

DIVINE

This pop culture icon—real name Harris Glenn Milstead—was more than just outlandish makeup, over-the-top wigs, and that one famous doo-doo scene. The late performer broke every rule and, in turn, as his dear friend John Waters put it, “made all drag queens cool.”

JOYCE J. SCOTT

With spunky humor and a godmotherly grace, this MacArthur Genius has used her intricate artworks to confront our country’s shadowy past while also shining a light on her hometown, where she still resides in Sandtown.

BLAZE STARR

Combining comedy with corsets, this iconic redhead showed the world how funny and fearless Baltimore could be, making the city’s 400 block of East Baltimore Street (aka The Block) the gilded epicenter of burlesque throughout the mid-century.

BARBARA MIKULSKI

At 4’11”, this Highlandtown native might be small, but she will go down in history as a mighty defender of the underdog, from her early fight to save Fells Point through her final days as Maryland’s first female senator.

REBECCA HOFFBERGER

Through the creation of the American Visionary Art Museum, this imaginative director has established a sanctuary for outsiders and cemented the city as an open-armed place full of whimsy and wonder.

Throughout history, few names have been more synonymous with this city than H.L. Mencken, the influential and irreverent writer famously dubbed both “the Sage” and “the Bard” of Baltimore. Over the years, we’ve idolized the cigar-smoking, middle-part-sporting Sun columnist as one of America’s most iconic voices, celebrating his sardonic wit, cocksure persona, and stubborn love for Baltimore. “Here,” he once wrote, “I can stretch my legs and feel at ease”—and he spent most of his life in the same house on Hollins Street.

There is much to admire about Mencken, but he was also a man of many flaws, some of which—namely his racism and anti-Semitism, which came to light posthumously—are harder to swallow. But as he was a critic quick to shoot from the hip—on politics, religion, the press—we like to think that, were he alive today, he would use his robust voice and gimlet-eyed perspective to critique, lightly ridicule, and offer solutions for the country, especially Baltimore. After all, he recognized this city’s ripe potential, just as many were about to abandon it. “This town is anything but perfection,” he wrote, “but I know of no other more charming.”