Arts & Culture

Jerrell Gibbs’ Meteoric Rise in the Art World

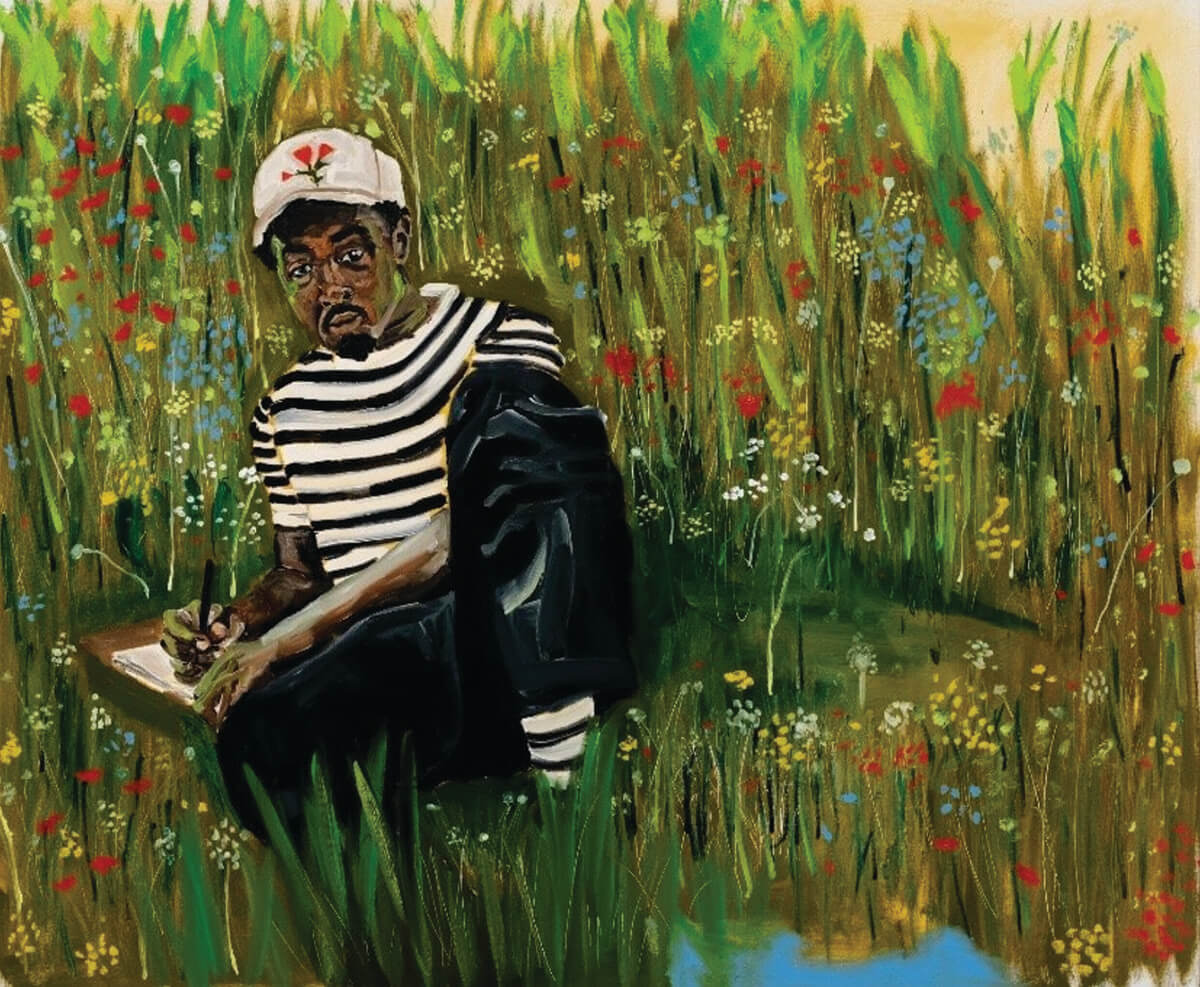

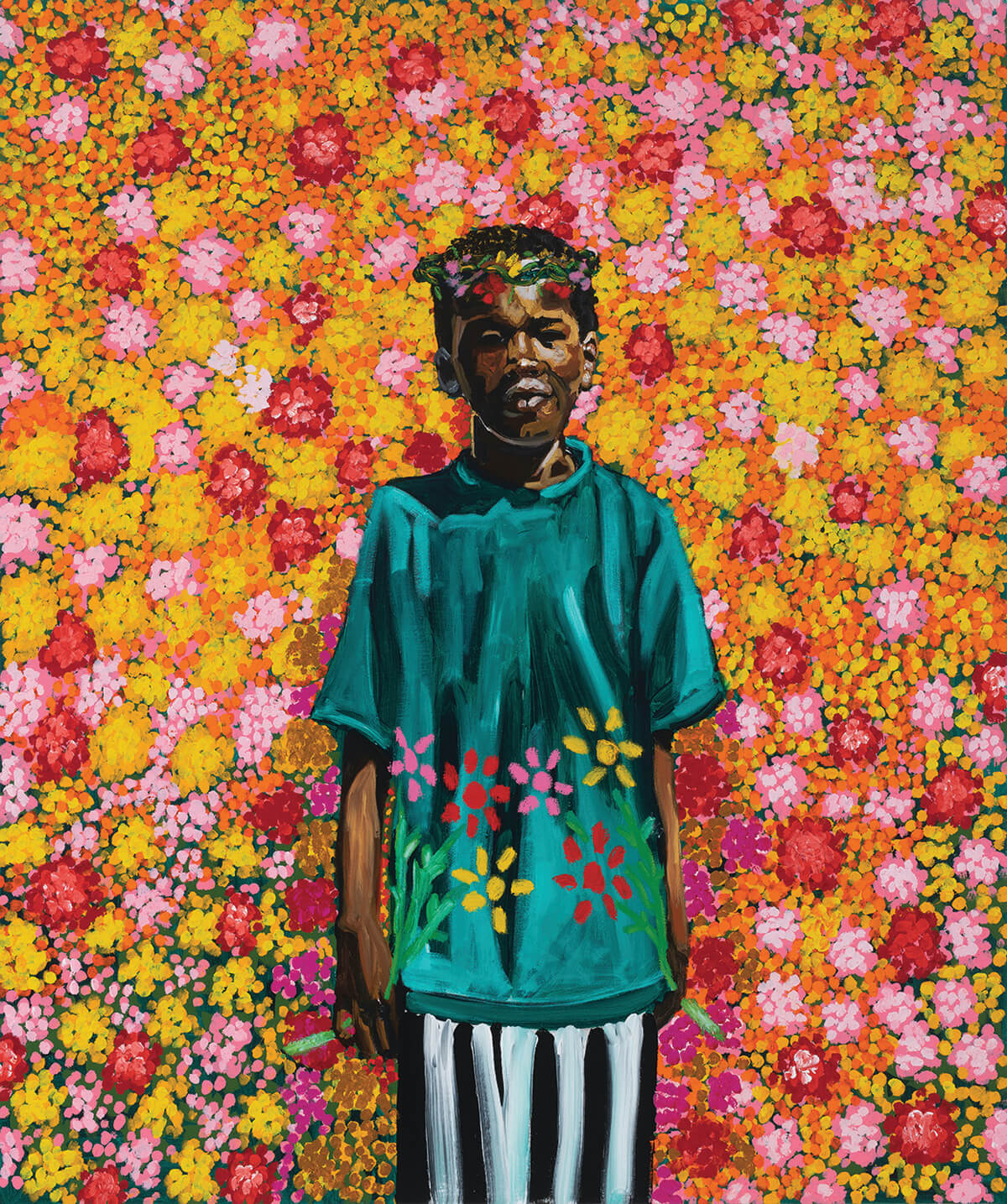

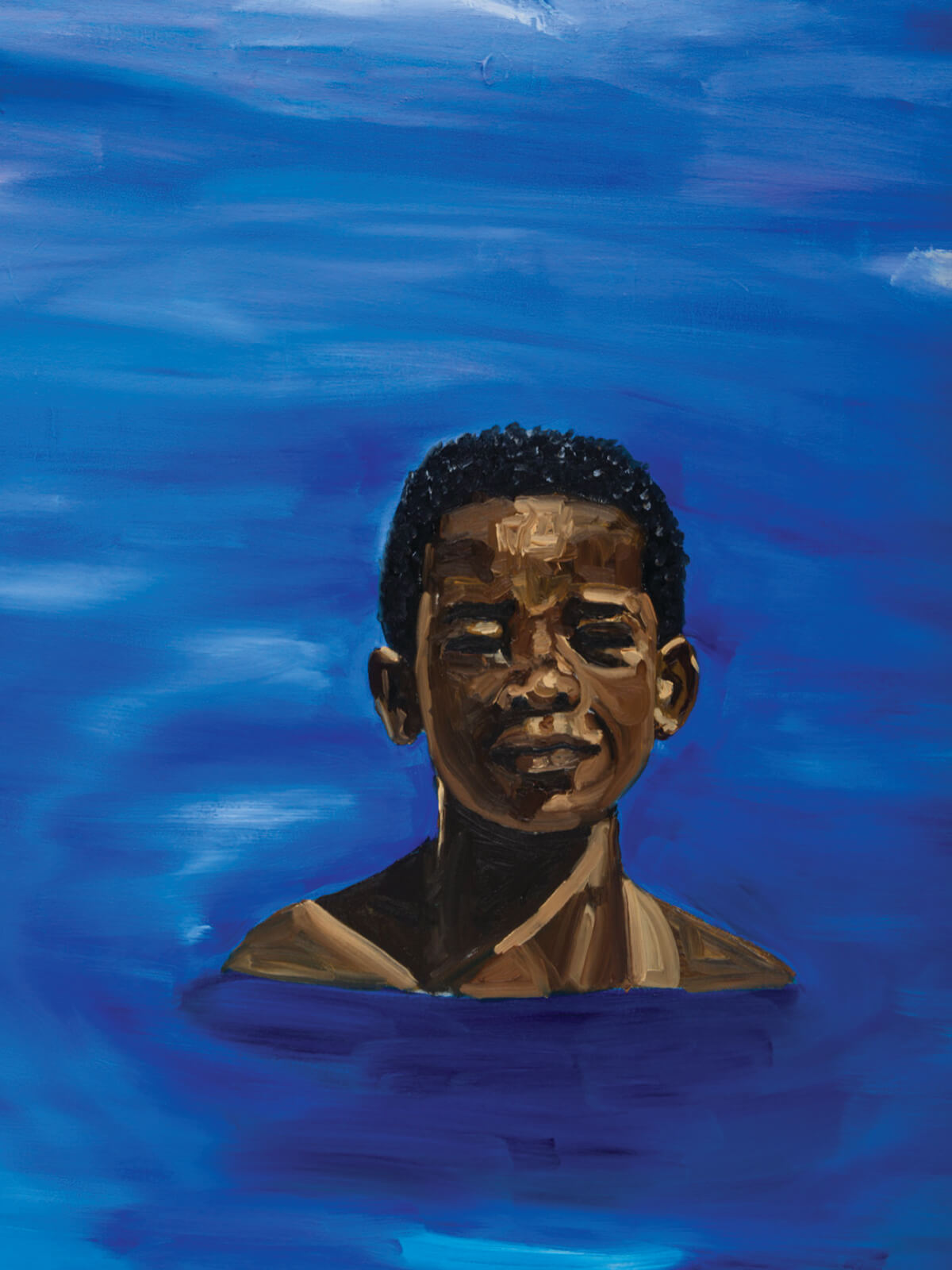

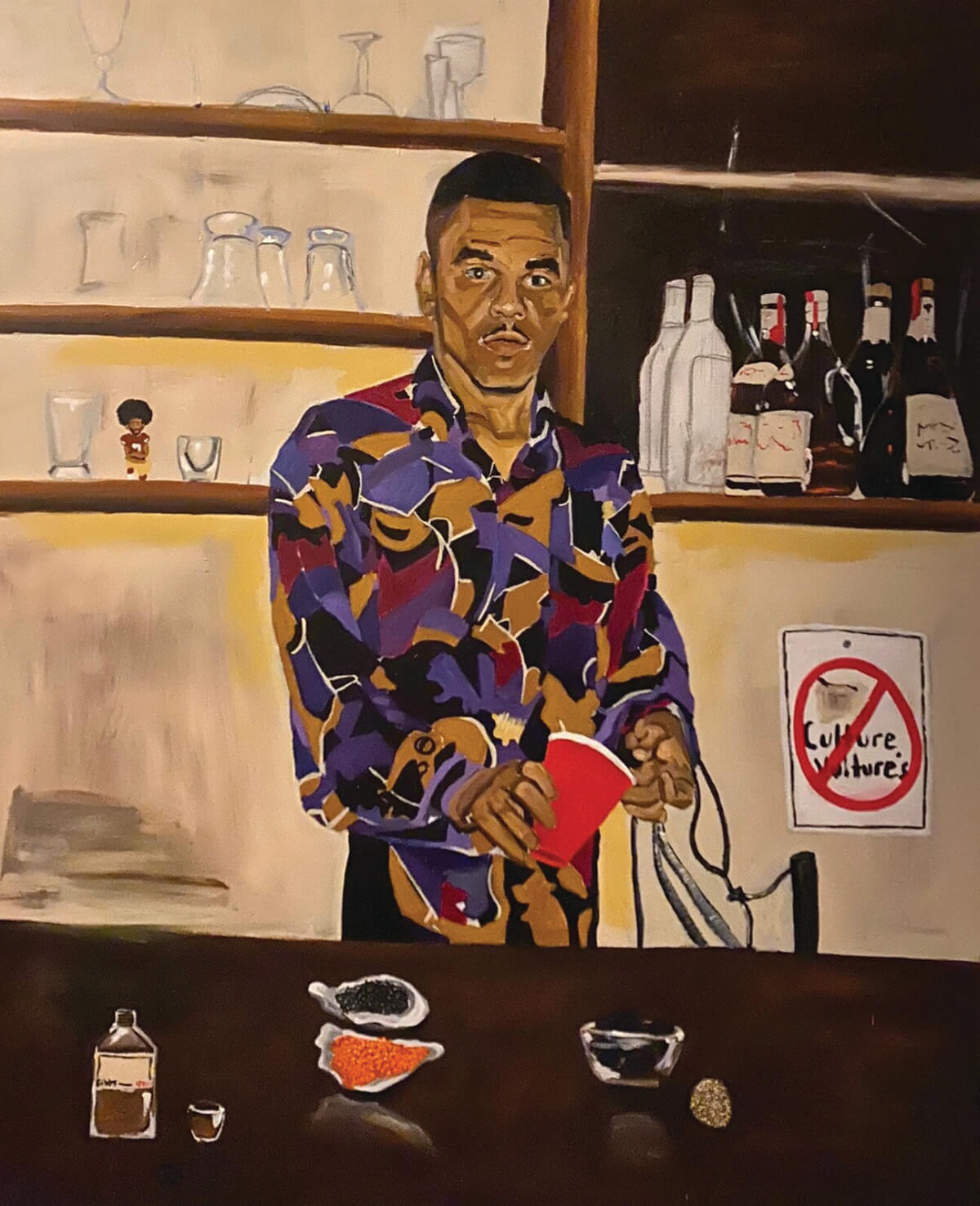

Painting the world he knows, Gibbs has earned an MFA, acquired representation through the Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, and solidified a reputation for his soulful portraiture that captures Black American life.

After dropping out of college (twice), Jerrell Gibbs worked as a home health aide while he and his wife raised their daughter in Baltimore County. For a while, he worked a day shift and a night shift simultaneously to provide for his family. During one of those night shifts, he found himself looking at a picture in his phone of his wife and daughter, and, on a whim, started sketching it—something he hadn’t done since he was a kid. Then he sent the finished drawing to his wife.

“I got it and was like, ‘Who drew this?’” Sheila Gibbs remembers, laughing. “It came to me by surprise. I was impressed. I was like, okay this could be a little something. Because we were newly married and struggling financially, I was like, ‘Why don’t you start tattooing or something, make us some more money?’”

Gibbs took his wife’s advice to heart and delved more deeply into sketching and also began designing tattoos. Noticing her husband’s growing interest, Sheila bought him an easel and art supplies the following year for Father’s Day, which furthered his new “hobby.” Not only did he begin experimenting with the practice of painting, he devoured books and other materials to learn as much as he could on the subject.

“I really started to get excited about being passionate about something other than football,” Gibbs recalls. “I just kept doing it, day in and day out, spending as much time and money as I could on painting. I just fell in love with it.”

Fast-forward seven years and Gibbs, now 34, has refined his craft through formal and informal mentorship, earned an MFA, acquired representation through the Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, and solidified a reputation for his soulful portraiture that captures Black American life. Most recently, he was selected to paint a portrait of Elijah Cummings, which hung at the Baltimore Museum of Art before moving to its permanent location inside the Capitol building. It’s likely just one of what will be many milestones in Gibbs’ career.

Gibbs has a distinct style, a penchant for conveying deep emotion and the various expressions of Black culture and experience through loose, fluid brushstrokes. But he didn’t start there.

When asked if he was exposed to art growing up in West Baltimore, Gibbs laughs. There were no artists in his family and little to no access to the art world that he’s now a part of. But in retrospect, he noticed from an early age that his doodles weren’t like those by other kids.

“What I was creating didn’t look anything like other people’s creations,” he says from his home in Baltimore County. “I always knew there was something there, but I didn’t have the community or the means to nurture that.”

When he dove back into art in his twenties, he would, piece by piece, find that community, as he connected with other artists and began showing work, initially at small venues like CCBC Essex, Howard University, and Dovecote Café.

When Jeffrey Kent, something of a Baltimore icon and mentor for emerging artists, first met Gibbs, he was still working as a medical aide and, as Kent remembers, painting “Peanuts” characters—specifically Franklin, the Black character in the comic strip. Gibbs reached out to Kent several times over the course of months, until the older artist finally agreed to meet with him

“Jerrell is very persistent and very goal-driven. And I guess at the time, his goal was to meet with me,” Kent says with a laugh. “We met at Red Emma’s, and he told me, quite frankly, he wanted me to be his mentor.”

Kent was renting out studios for a low rate and invited Gibbs to utilize a space in his building, which would become Gibbs’ first studio. Kent also gave him some pointers—how to conduct himself as an artist, how to navigate the art world. Soon after, Gibbs quit his day job and began studying at Maryland Institute College of Art.

“Here’s a Black man in Baltimore, married at 26 with a daughter, and his wife is 100 percent in support of him quitting and becoming an artist,” Kent recalls in amazement. “I’m like, and you’re painting ‘Peanuts’ characters? [His family] deserves every bit of success they’re getting because of the sacrifices they have made for him to be where he is.”

Despite never completing a bachelor’s degree, Gibbs was accepted into MICA’s master’s program at the LeRoy E. Hoffberger School of Painting and started in the fall of 2018.

“It was immediately obvious that Jerrell was very focused and disciplined, very together, always working hard, and very artistically ambitious,” says MICA painting professor Stephen Ellis. Ellis remembers taking Gibbs and the rest of his class to see the Henri Matisse paintings at the BMA and watching the young man’s work evolve almost overnight. “He just absorbed the lesson in those paintings and applied it to his own work in literally a matter of days. It was amazing,” he says.

Gibbs, who had mostly been working with acrylics, began using, then mastering, oil paint and “never looked back.” Also while still a student, four of his paintings were selected for inclusion in the 2019 show “Blackface: A Reclamation of Beauty, Power, and Narrative” at Galerie Myrtis, which proved to be pivotal for his career.

Jessica Stafford Davis, who co-curated the exhibit with gallery owner Myrtis Bedolla, had met Gibbs years prior and suggested him as an artist to include. “As we did studio visits and he shared the narrative behind his work and these wonderful images of Black life, I was like, ‘Oh my God, this kid is genius,’” Bedolla says.

The first piece in the show to sell was his—an oil painting titled “Git It” that depicted a grandmother dancing. His remaining three paintings sold immediately, too, and people began asking for more.

“I really admire his conscious effort to depict Black families at leisure,” says Bedolla. “A lot of what’s addressed in Black art is about our fight against oppression and racism. Jerrell brings another important conversation but one that reminds us of our humanity, our leisure, our play, and that’s a part of our culture that also needs to be shared. His work is a reflection of humanity, and my hope is that people of all races and cultures and belief systems will see themselves in it.”

Stafford Davis echoes that sentiment and notes that his collectors cross generational and geographical lines. “I think it’s because the subject of the work is universal,” she says.

Gibbs’ online bio alludes to this universality, stating, “Gibbs invigorates banal representations of Black identity by depicting empathy, inviting the possibility for a spiritual connection.”

When talking about his process for painting portraits, Gibbs describes something akin to an actor getting into character—and perhaps it’s through this personal process that he’s able to capture something transcendent.

“It’s about me,” he says, simply. “That’s why there’s so much emotion within the figures in the paintings, because I’m placing myself into their space. I’m thinking about myself and whatever I’m going through and allowing the figure to be the avatar for me, whether it’s male or female. . . . It’s almost like becoming the thing, becoming the person, in order to relay the message.”

After Gibbs was commissioned by the BMA to paint the portrait of Elijah Cummings, he read articles online about the congressman, as well as Cummings’ 2020 book We’re Better Than This in preparation. He had long conversations with Cummings’ widow, Maya Rockeymoore Cummings. He watched YouTube videos of Cummings speaking and paid close attention to his disposition, even if it was a clip of him sitting in an audience.

“Becoming the person,” Gibbs repeats. “I wanted to see, hear, and find out who this person was to the best of my ability. I wanted to become Elijah Cummings so I could portray his true essence.”

Certainly, Gibbs’ demonstration of skill and technique in portraiture caught the attention of the BMA selection committee, but it was more than that.

“I thought about his trajectory,” says Kent, a committee member. “The other artists were just as talented, but Jerrell was the only one represented by a gallerist, he was already being collected by museums, and these things were moving him into the world stage, as we’re seeing now. And also his work ethic. It’s unmatched.”

Gibbs says his successes have come through routine, which keeps him grounded and focused. He wasn’t always so structured. Around 2016, something the motivational speaker Eric Thomas said caught his attention.

“He was talking about taking advantage of the opportunities that you have in the time that you have, and I realized that a lot of my losses were coming from the fact that I wasn’t intentional about the hours in my day,” Gibbs recalls. “Right then in that moment, I made an intentional shift about the time I was spending with my craft, with my family, with my friends, with myself. I just got really specific about not wasting a lot of time.”

On weekdays, for instance, he takes his daughter to school, works out, then spends four to five hours painting in his current space at Parkdale Studios. He also makes time every other day to be tutored in French—a practice he began after gaining representation from Mariane Ibrahim Gallery, which has locations in Chicago and Paris. He wanted to learn the language so he’d be able to conduct a basic conversation, especially when, in September, his work will be featured in a solo exhibition at the gallery’s Paris location.

In April, Gibbs went to Paris for the first time, along with his wife and daughter. As he immersed himself in the culture, something funny happened.

“What really struck me while I was in Paris was that I started to love Baltimore that much more,” he says. “I saw what makes Paris special—the architecture, the cuisine, the artwork, the Louvre, everybody walking around smoking cigarettes, people eating outside. It was beautiful. They even display the macarons in a way that was creative. This is why people love to go there. Why do people like going to Baltimore?”

He thought about that a lot. And after reminiscing and waxing nostalgic about his favorite pastimes back home—visits with his grandma, getting crabs from Lexington Market—he thought, what better way to express his love for his home city than to share his Baltimore with Paris.

Gibbs was preparing to return to Paris and work on his exhibit for a full month in June (our interview was conducted in May). Among croissants and macarons, he planned to make paintings of blue crabs. With the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre as his backdrop, he would capture West Baltimore and folks sitting on stoops and enjoying backyard barbecues.

“I was thinking about what I really appreciate about an artist and realized the artists that I gravitate to always tell me about their experiences and where they’re from,” Gibbs says. “I’m thinking about Kanye West. His first album, The College Dropout, he was talking about Chicago and his upbringing and experiences. Jay-Z, same thing. Kendrick Lamar talking about L.A., talking about Compton. J. Cole talking about North Carolina. I fell in love with them because of that. So why wouldn’t I bring Baltimore to Paris and talk about all the beauty that is here?”