Arts & Culture

On With The Story: Remembering Iconic Maryland Novelist John Barth

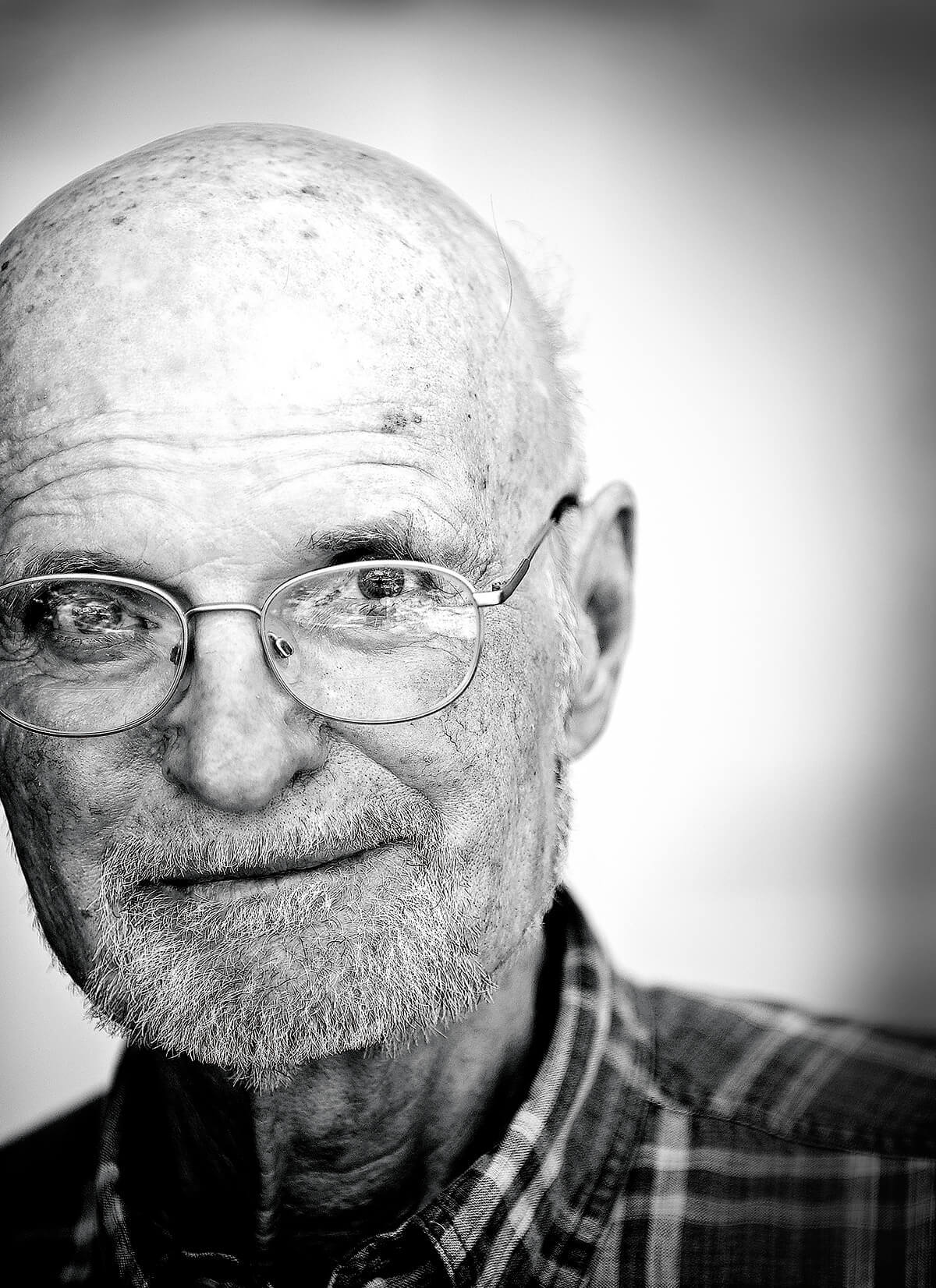

Take a look back at our November 2008 profile of the celebrated Cambridge-born author, who passed away this week at 93.

[Editor’s Note: Iconic postmodernist writer John Barth, who called Maryland’s Eastern Shore home, passed away on April 2, 2024 at the age of 93. Below is our 2008 profile of Barth, for which former arts and culture editor John Lewis spent time with him in Chestertown, in the autumn of his years.]

John Barth still gets a charge out of being mentioned in a pull quote. Even after decades of circulating in the upper echelons of literary fiction, that sort of acknowledgment hasn’t lost its visceral appeal.

In fact, if you perused The New York Times Book Review a few weeks back, you may have noticed an ad on the inside cover comparing Hannah Tinti’s The Good Thief to Barth’s “picaresque classic, The Sot-Weed Factor.”

A certain iconic author noticed it.

“I did see that,” says Barth, between bites of mahi-mahi and sips of pinot grigio at The Imperial Hotel in his hometown of Chestertown. “It’s very pleasant. If you’re a novelist, you hope that your stuff stays in print and that someone still remembers you.”

Actually, neither seems to be much of a problem for Barth. A stroll to The Compleat Bookseller down the street confirms that his work remains in print; the shop stocks no less than four Barth novels. And at this point, Barth has attained that rare pinnacle of respect for a contemporary author: adjective status. In lit circles, to be “Barthian” is to be post-modern, meta-fictive, and engaged in the sort of intellectual gamesmanship that gives rise to honorary degrees and graduate seminars.

Barth gets mentioned regularly in the same breath as Pynchon, Nabokov, Vonnegut, and even Joyce. He’s been called “one of the greatest novelists of our time” (The Washington Post), “a master of language” (Chicago Sun-Times), “a genius” (Playboy), “perhaps the most prodigally gifted comic novelist writing in English today” (Newsweek), and “a comic genius of the highest order” (The New York Times).

He’s swooped in and out of the mainstream, sparked lively debates, inspired a younger generation of innovative scribes, and even infiltrated the Axis of Evil. (Barth recently learned that he’d won a literary prize in Iran and four of his books have been translated into Russian.) Throw in a National Book Award (for Chimera in 1973), grants from the Rockefeller Foundation and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and election to the American Academy of Arts and Letters and you have more than a distinguished career: You have a legacy to consider.

So why the self-deprecating talk about being remembered? It can’t be the pinot grigio talking—he’s still on his first glass. The ruminations of a reluctant genius? No, Barth fully embraces his prodigious gifts as a writer and doesn’t shy from his status as a man of letters. He’s refreshingly old school that way, thinking of such things as badges of honor earned during a half century working at this craft.

No, it’s more likely attributable to another presence at the table: Father Time. Barth, who turns 79 next May, appears to be remarkably fit and says he’s in good health—he’d seen three doctors the previous day and gotten a thumbs-up from each of them. Still, he feels “the law of averages hanging over me like the Sword of Damocles.”

Barth gets mentioned regularly in the same breath as Pynchon, Nabokov, Vonnegut, and even Joyce. He’s been called “one of the greatest novelists of our time.”

He’s well aware that he hasn’t published a full-length novel since 2001’s Coming Soon!!!, despite being, by his own account, “a novelist by temperament and not a short story writer—a marathoner and not a sprinter.”

His last few books have nonetheless been comprised of short stories or novellas. A new book, The Development, continues along those lines by stringing together nine related stories, all of them set in a gated community on the Eastern Shore.

“I guess I’m getting older,” says Barth, “but I’ve always been fascinated by short forms. And it doesn’t matter to me if critics find that the things I’ve written recently don’t measure up to some earlier book. Now, I’m writing for my own pleasure, and, I hope, the pleasure of some readers. I’m just happy to be in print, with a publisher. Never mind that the advances go down, and the print runs get smaller.”

That may be so, but one thing hasn’t changed: Barth relishes being a storyteller, (not so) plain and (not so) simple.

In conversation, Barth can sound downright annotated, like the meta-fiction guru he is. As practiced by disciples such as recently deceased David Foster Wallace, it’s a style that allows commentary on not just the plot, but also the devices being used to tell the story. Much like his novels, he diverts to contexts and definitions that move the discussion laterally.

When speaking of novellas, for instance, Barth notes, “The market for them is gone.” He adds commentary (“the novella is an interesting form that was popular from the time it was invented”), along with when (the 18th-century), where (Germany), and who popularized it (Goethe). He opines that novellas embody “a lovely narrative space.” He then playfully defines a novella as “a work of fiction too long to sell to a magazine and too short to sell to a book publisher.” And finally, he offers advice from one who knows: “When you perpetrate one, you usually need to add on a few short stories [in order to sell it].”

He comes across as cerebral and urbane, a refined academic. His table manners are impeccable, and he refers to the waiter as “chap.” If you guessed he was from Cambridge, you’d be correct. But that wouldn’t be England’s renowned university town. And it’s not Cambridge, Massachusetts, home to Harvard. Rather, it’s Cambridge, Maryland, known primarily for its crabs and oysters, mosquitoes, and racial unrest in the 1960’s.

Barth lived on Aurora Street in East Cambridge, a neighborhood full of maple trees and modest homes. He had two siblings: an older brother, Bill, and a twin sister, Jill. After family and friends took to calling him Jack, Barth reckons he heard every imaginable variation on the nursery rhyme.

His father had a shop, Whitey’s Candyland—which Barth describes as a “Norman Rockwell-ish small town soda fountain”—on Race Street, between Carton’s clothing store and the old Opera House. The irony of having a store called Whitey’s, on Race Street, during the racial upheavals of the 1960’s is not lost on Barth.

“Can you imagine?” he asks, shaking his head. He then lauds the fact that his hometown recently elected an African-American woman as mayor.

In Cambridge though, there’s scant public recognition of Barth: no markers in front of the Aurora Street house or at Whitey’s old location, and the house on Water Street where Barth wrote his first novel, The Floating Opera, remains similarly unadorned.

But at the mention of the name Barth, the current owner of the Water Street house, out sweeping his sidewalk, lights up. “He was a natural storyteller, the best you ever heard,” says Wayne Warner. “He was extremely erudite.”

But Warner isn’t talking about Jack; he’s talking about Whitey. “If Jack could write as well as his father talked, he’d really be doing something,” he says. “It seems like Jack takes 10 pages to tell something that could be told in one.”

Warner knows his house merits a footnote in literary history, but he’d still rather discuss Whitey’s skills as an after-dinner speaker. “He was genuinely funny,” he says, smiling and nodding his head.

Barth, himself, addressed the subject in the Spring 2007 issue of The American Scholar. “Whitey came into his own as an entertainer, in demand year after year,” he wrote. “Never a clown, he was a humorist locally renowned for his joke-telling from at least the early 1940’s until his death in February 1980.”

Besides passing along the comic storytelling and longevity genes, Whitey, who dropped out of high school, helped expose his son to popular and modernist fiction. Barth devoured the paperbacks his father stocked at the shop, and it was there that he first encountered books by Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, and H.P. Lovecraft, along with William Faulkner’s Sanctuary and John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer. That was better than he got at school, even though he was on an academic track—as opposed to the agricultural and commercial tracks.

He graduated from high school largely unschooled. In fact, Barth has said, “Nothing since kindergarten prepared me for [college]” and noted that, at his high school, career counseling amounted to a 10-minute talk with the phys-ed teacher.

As a teen, he’d developed a love of jazz, so he figured he’d try his hand at music. He was a competent drummer, but imagined becoming an arranger like Billy Strayhorn or Pete Rugolo. He enrolled in a summer session at Juilliard, where he was placed in elementary theory and advanced orchestration classes, which indicated something of a gap in his musical knowledge. He soaked up New York’s jazz scene, listening to the likes of Illinois Jacquet in Harlem clubs, and applied himself in class. But by summer’s end, he left Juilliard convinced he had little more than “an amateur flair” for music.

He returned to Cambridge and learned he’d won an academic scholarship to Johns Hopkins University. Barth arrived in Baltimore in the fall of 1947. He declared a journalism major and quickly learned it wasn’t his forte. But as part of the major, he was required to take a fiction or poetry class. He opted for fiction.

“It was the opposite of what happened at Juilliard, where I thought I had some talent,” he told Baltimore in 2004. “When I stumbled into fiction, I had the unequivocal feeling that this was my true calling: All I had to do was learn it from scratch!”

He augmented his rigorous coursework with plenty of outside reading, some of it done while working at the campus library or the Chevrolet plant on Broening Highway. At the library, he shelved rare editions and pored over the likes of a classic, multivolume edition of One Thousand and One Nights. At the auto plant, he worked the night shift as a floor checker, making sure all the assembly line workers were present and accounted for. It was a job that left him plenty of time to read.

“I plowed through The Harvard Classics, one after the other,” he says. “I started with volume one and proceeded to volume two and three and went through the entire shelf from left to right.”

It was a sign of his “anal-compulsive ness,” says Barth, before adding that he often “resists being taught by others.”

“It was the opposite of what happened at Juilliard, where I thought I had some talent. When I stumbled into fiction, I had the unequivocal feeling that this was my true calling: All I had to do was learn it from scratch!”

Still, university life agreed with him, and he pretty much spent the next 50 years at college. He graduated from Hopkins, enrolled in the university’s doctoral program, dropped out, and landed a teaching job at Penn State. It was an entry-level position, one that required him to either get a Ph.D. or publish a book within three years. Barth wrote The Floating Opera, about an eccentric Cambridge attorney’s existential hijinks, the summer after his first year at Penn State and began circulating the manuscript to various publishing houses. Six of them turned it down.

By that time, he was married with three children, and the pressure was enormous. To his great relief, the seventh publisher bought the manuscript, thereby solidifying his standing at Penn State and launching his career in academia. He got another boost when The Floating Opera was nominated for a National Book Award in 1956.

He remained at State College for 12 years, moved to SUNY/Buffalo for the next eight, and landed back at Hopkins in 1973, all the while penning increasingly dense, shape-shifting works such as The Sot-Weed Factor, Chimera, Lost in the Funhouse, and The Tidewater Tales.

Such books made Barth’s literary reputation, but they also baffled some readers. The same New York Times that dubbed Barth a “comic genius” also referred to some of his books as “tomes that only an English professor, and not all of them, would take down and spend time with.”

Undeterred, Barth consistently upped the ante by challenging his readers and himself, and teaching helped him reinvent and reconsider his methods. At Hopkins, he chaired the Writing Seminars and mentored hotshot writers.

“He took it all very seriously,” says Tristan Davies, a former student of Barth’s who is currently a Senior Lecturer at the Writing Seminars. “He ran a very disciplined workshop and wasn’t an oppressive presence at all, in part, because he was able to take genius-level material and distill it into thoughtful observation. Maybe he got that from Whitey.”

Barth also insisted on teaching an introductory fiction class for undergraduates. “I deliberately called it ‘Rudiments of Fiction,’” he says. “It was fiction writing 101, although it was actually below that level. Teaching that class gave me a chance to think about first principles: What is a story? What is fiction? It may be a postmod approach, but I liked thinking about those sort of things at least once a week.”

He did that for 22 years, until retiring from Hopkins in 1995.

Back at The Imperial Hotel, a woman on her way to an adjacent dining room spots Barth, does a double take, and interrupts. “John Barth?” she asks. “The famous John Barth?” She approaches his table and introduces herself. “Do I know you?” he asks, a bit sheepishly, as if this might be a senior moment. “I’ve heard you speak at Washington College several times,” she says, “and I

used to deliver your mail.”

Recognition flashes across Barth’s face, as she continues: “I was always interested in the postcards you wrote. I practically drove off the road trying to read them.”

Barth ignores the invasion of privacy issues raised by such a comment and, instead, praises her performance. “I don’t want to besmirch your successor,” he says, “but our mail delivery used to be much more punctual than it is these days. You did an excellent job.”

She thanks him and departs, looking pleased.

“That’s life in Chestertown,” says Barth, looking pleased himself.

Since his retirement, Barth and his second wife, Shelly, split their time be tween a house on Langford Creek, near Chestertown, and a second home in Bonita Springs, Florida. They visit Barth’s three children, who are scattered across the country, when they’re able. These

days, the couple only comes to Baltimore for what Barth calls the five D’s: doctors, dentists, department stores, delicatessens, and dining out.

No matter the locale, Barth still writes every day. After breakfast, he does stretching exercises to warm up “body and spirit,” he says. Then, he goes to his desk and puts in wax earplugs, a habit from when his children were little. He reviews a printout of the previous day’s effort, usually two to four pages, uncaps his Parker 51 pen—purchased at an English stationery store that advertised itself as the original site of “Mr. Pumblechook’s Premises” from Dickens’s Great Expectations—and begins to write.

His first draft is always composed on loose-leaf paper in a binder purchased during freshman orientation in 1947. Every one of Barth’s books has been written in this binder, with (since 1964) the same Parker pen.

“That’s the kind of anal-retentive I am,” he notes. “But it’s a happy routine.”

Barth wrote aspects of living in both Chestertown and Bonita Springs into the new book, which is his wittiest and most accessible work in years. The Development takes place in a gated community, not unlike where the Barths live in Florida, but it’s set on the Shore. Both the real Bonita Springs and Barth’s imagined Heron Bay Estates include a mix of condos, duplexes, coach homes, and detached houses. Both are beautifully maintained and handsomely landscaped. Both are prone to intense storms. Both are populated mostly by wealthy conservatives, with a few stock liberals in the mix. You might guess who the real life liberals are.

“When Shelly and I bought the house, we had properly mixed feelings about the whole gated community thing,” says Barth. “It’s that whole us and them thing.” (A story in The Development, “Us/Them,” deals with the same issue.)

The book also includes “a failed old fart fictionist” named George Newett. With the middle initial “I” who turns out to be the writer of these stories. “By George I. Newett” would be his byline. You can practically hear Whitey chuckling at that one.

As always, it’s dedicated to Shelly. In fact, all of Barth’s books have been dedicated to her since 1970, the year they married. “She is my editor of first resort, my best friend, and my severest critic,” says Barth. She’s also a former student. They met when Shelly was a Penn State undergrad and reconnected a few years later at a reading in Boston. Shelly declined to be interviewed for this story, but Barth doesn’t shy from talking about her. He lauds her as an educator, now retired from teaching English at St. Timothy’s prep school in Baltimore County.

Every one of Barth’s books has been written in the same binder, with (since 1964) the same Parker pen. “That’s the kind of anal-retentive I am.”

He exudes not only a genuine love and respect, but also a profound sense of gratitude. And considering the fate of some of his peers, he feels especially fortunate. He recalls a gathering in New York City that also included Donald Barthelme, John Hawkes, and Kurt Vonnegut.

“I remember looking around at the group, and Donald whispered to me that it seemed a terminal sadness had come upon Vonnegut,” says Barth. “This was quite awhile ago, 15 or 20 years before his death. And I’ve seen it come over others, since then.” He pauses a moment, before getting to the real point of this story: “Even though there’s a fair amount of autumnality in my fiction these days, I don’t

feel like that so much—in part, because my physical health is good. But it’s largely because my personal and domestic life has been a real source of bliss, support, and satisfaction.”

So when Barth goes to his writing room, it isn’t as some tormented genius full of postmodern angst. Rather, it’s as a happily married man with a story to tell, a story he’ll no doubt infuse with structural twists and turns of phrase, and, ultimately, dedicate to his wife. That’s the way it’s been, for nearly 40 years.

He has no intention of it changing any time soon.

In fact, he’s written 100 pages of what may turn out to be his next novel. “I’m cheered by the fact that there are plenty of cases where writers did some of their best work very late in the day,” he says. “I used to remind my writing students to, as they get older, keep in mind that Sophocles, as legend has it, wrote Oedipus at Colonus when he was 90.”

He leans forward: “Jack Hawkes used to tell me 30 years ago, ‘I can’t help feeling that I’ve reached my peak.’ “And I’d tell him, ‘Jack, I intend to reach my peak at about age 80.’”

He flashes a smile and lowers his voice: “Then, I’ll go into a very slow decline.