Arts & Culture

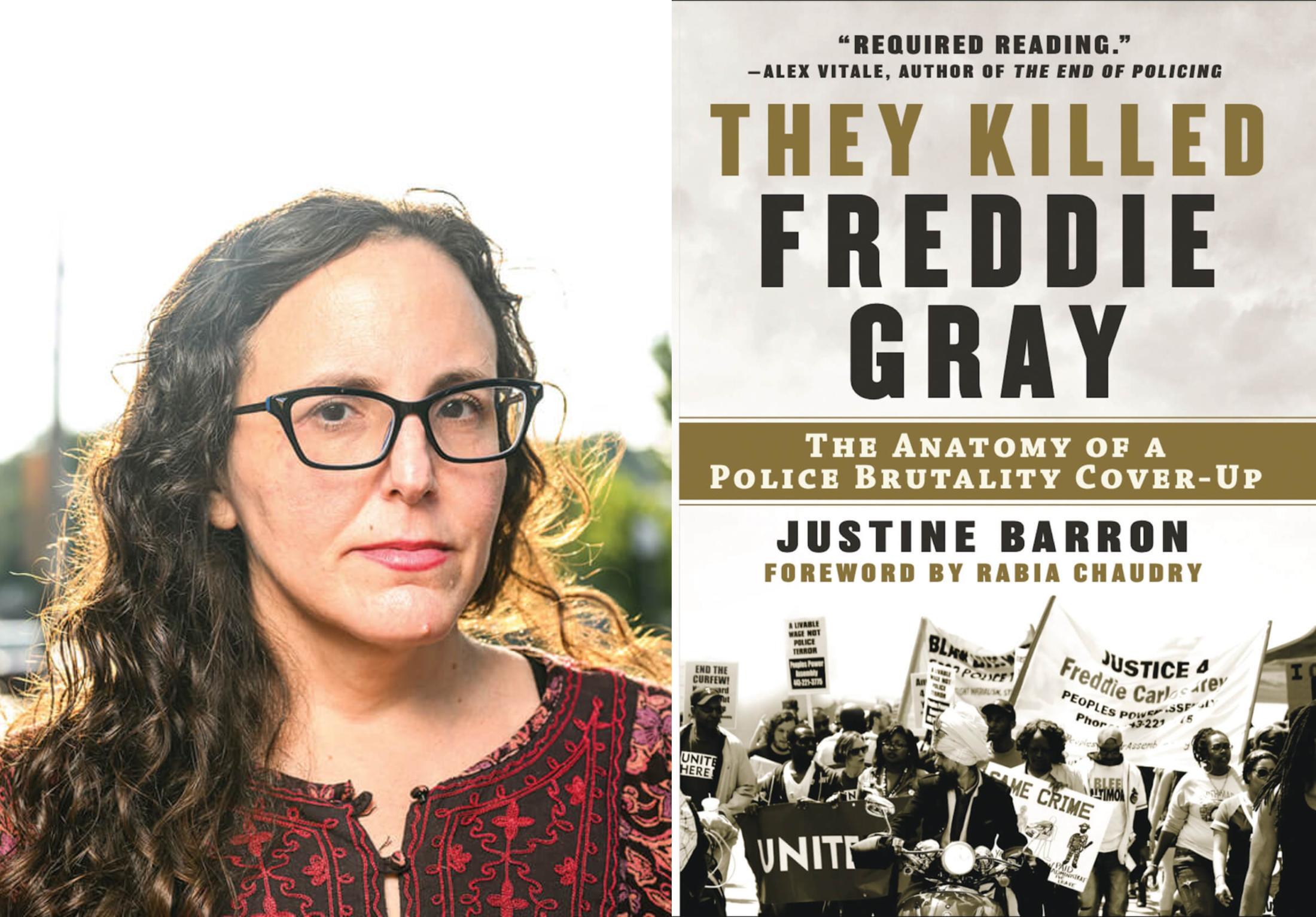

Justine Barron’s New Book Presents the Fullest Story of Freddie Gray’s Death to Date

In 'They Killed Freddie Gray: The Anatomy of a Police Brutality Cover-Up,' the independent journalist analyzes problems with the established narrative that Gray was fatally injured during a “rough ride.”

The uprising after Freddie Gray’s death put a spotlight on the racialized history and lack of accountability around police brutality in Baltimore. The scrutiny only intensified when Gray’s death was ruled a homicide and now-former City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby responded by indicting six police officers on charges, including one for second-degree murder, related to Gray’s broken neck. Ultimately, of course, prosecutors failed to win a single conviction.

Afterward, Mosby blamed the police department, alleging a cover-up. But what if that were true and the narrative Mosby and her prosecutors laid out was flawed from the start? What if Gray wasn’t fatally injured during a “rough ride,” as we were told? The speculative cause by the medical examiner was partially based on information brought forward by the defendants themselves. What if a shackled Gray was thrown into the police van headfirst, as eyewitnesses attest, breaking his neck?

In They Killed Freddie Gray: The Anatomy of a Police Brutality Cover-Up, independent journalist Justine Barron analyzes, with new information, problems with the established narrative. In over 300 meticulously reported pages, Barron presents the fullest story to date of Gray’s death and the failure to hold the BPD accountable.

Your reexamination of Gray’s death comes after widespread documented corruption and the Gun Trace Task Force scandal. Maybe people are willing to take a second look at the story we were told about how he died?

I think that’s partly true. I also think something about the Freddie Gray case has remained fixed in people’s minds. For many, it was about cops, and in their minds, the very worst thing they could have possibly done is not call for a medic on time. But they definitely didn’t kill him with their hands.

Hospital records state Gray’s neck injury was a jumped facet and there’s only one mechanism that could’ve caused it, which is going headfirst into a hard surface. Why did the medical examiner and then prosecutors discount the testimony of eyewitnesses?

Within days of Gray’s death, they do an autopsy and confirm what the hospital records show. But medical examiner Dr. Carol Allan is not told by police, or anyone, that he was thrown in the van. She’s told that he was handled fine. She is even asked in one meeting, “Could it happen from Freddie Gray being shoved in the van?” She says, yes—she just didn’t know [that]. So, she comes to this conclusion that it likely happened while the van was moving and that’s really good for the police department and the prosecutors went along with that, too.

Years earlier, Jeffrey Alston suffered a broken neck while shackled in a police van in Baltimore. As with Gray, the police tried to claim he’d injured himself. Alston, however, survived—as a paraplegic—and said he was injured getting tossed into the van. Yet, without direct evidence, the “rough ride” narrative becomes gospel.

I think the big thing was Marilyn Mosby prosecuting these cops with such serious charges. Her stance, her statements about the police and on policing, and the level of charges were in some ways unprecedented. What happened was that even the witnesses thought, “Well, maybe he was killed in a rough ride.” Why? Because people thought if Marilyn Mosby is taking on the police and she’s saying this, she must know something we don’t know. After [the first trial] was such a dud, the eyewitnesses started to feel like, “Wait, I should go back to what I originally felt.”

It takes someone on a mission to do this amount of investigative work. What drove you?

A few missions, I guess. Certainly one was to correct the historical record. It’s enormously aggravating to see Wikipedia have it wrong, and then also see people tweet about [Gray’s death] every year on the anniversary and have it wrong. It’s also frustrating to see certain people held up as heroes that actually were helping lead the cover-up. I don’t know what you call that motivation, but it feels like gaslighting.

You also reflect on systemic problems highlighted by the Gray case—the relationships between police, prosecutors, crime labs, and medical examiners—and the media’s approach to reporting on crime and criminal justice issues.

There are potential conflicts of interest that I didn’t see being discussed, including the enormous protection racket around police brutality. We’re also still talking about autopsy reports as if these are scientific documents. But it’s also the way that the media and the public takes things at face value—video evidence, autopsy reports, statements from officials, and who they’re told are the heroes and the villains. The need to deconstruct and undo these myths comes from a deep place for me.