Arts & Culture

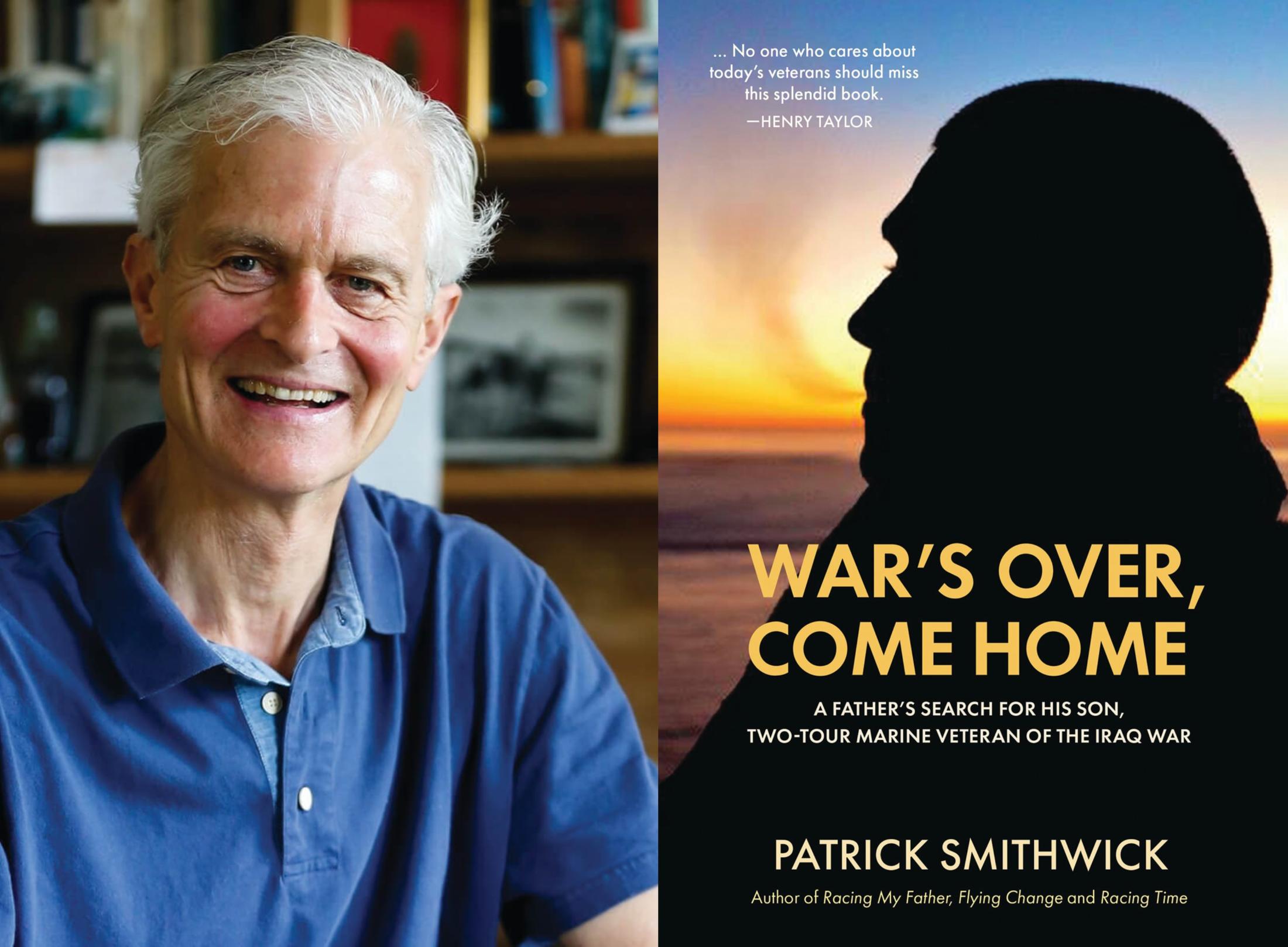

Patrick Smithwick’s Latest Book is His Most Heart-Wrenching

The Monkton author's new book, 'War’s Over, Come Home', chronicles his family’s struggle to help their oldest son as he suffers through PTSD after two tours in Iraq.

Patrick Smithwick has written three previous memoirs, all connected to horse racing, family, and loss. His father, A.P. Smithwick, one of the greatest steeplechase jockeys ever, died at 46 from cancer. Readers are likely to find his latest work, however, his most heart-wrenching.

In War’s Over, Come Home: A Father’s Search for his Son, Two-Tour Marine Veteran of the Iraq War, the Monkton author, longtime teacher, horse trainer, and former competitive rider chronicles his family’s struggle to help their oldest son as he suffers through PTSD after two tours in Iraq.

The “search” in this case is literal. Andrew Smithwick eventually became homeless after returning to civilian life, using his U.S. Marine training to survive in far-flung corners of the country as his family desperately sought to track him down and get him mental health assistance.

Although he also has a newspaper and magazine background, including a brief stint at this magazine, Smithwick has not set out to objectively report on veteran PTSD or homelessness. Instead, he keeps the focus on his son’s struggles and the loving, frustrated efforts of his family—which in turn brings PTSD and the tragedy of veteran homelessness into extraordinarily sharp relief.

As a parent, one of my first thoughts was around what must be Andrew’s profound loneliness as he spends day after day simply walking and camping by himself.

Yes, definitely. He was our most social child. You can tell from one of my favorite pictures in the book, where my wife is reading to him and he’s looking up at her. He loved being with the family. When he was in the Upper School at Boys’ Latin, his friends would come over [a lot]—he was sort of the leader of the pack. It really hurts thinking of him alone.

For the most part, the book was written in real time, between 2017 and 2019, as you and your family search for Andrew in several states. How hard was writing during that process?

Sort of painful. But I just got up and did it, because I knew from my writing experience that things would drift away and become foggy. I was making notes and I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do [with it] initially, but I knew if I didn’t get it down immediately that I wouldn’t be able to do it.

Why did you write the book?

I knew when we started on these searches this was a microcosm of experiences other people were going through. I met so many people who had similar experiences. I met parents who had lost children, relatives, or friends to PTSD and homelessness. And I met homeless people themselves. Every time I’d talk to someone, I would learn more about it and realize maybe one out of every four or five people would have some relationship to this story. I’m writing this for all of them, too.

The book ends with a late-2022 update on Andrew. He seems to be doing okay physically even as he continues to live “off the grid.”

Working on the book and getting a publisher, more time had passed. So, I put an update in the postscript and it kind of ends in an upbeat way, with some positive information about my daughter getting married on our farm and hearing that someone had seen Andrew.

One of things you point out is that you, like most of us, during periods of great personal difficulty tend to compartmentalize as a means of coping. At the same time, beneath that, a part of you remains hopeful that someday Andrew will either tire from—or heal enough from—the outdoors, the hiking and camping, that he connects back to some type of services or returns to the family fold.

Yes, either one of those two things. The main thing that I notice from talking to so many people that work with the homeless is the main ingredient for them to have a successful recuperation is to have a place, a little place, where they can live and it can be their home. A small apartment or whatever to keep their stuff and get cleaned up and go out. There are 67,000 homeless vets the last time I checked. I’m hoping they can start getting more help. And Andrew is one of them.

What do you hope people take away?

Well, if you see a homeless vet on the sidewalk or in a city or somewhere, you don’t have to just be afraid, walk away, and lower your eyes. You can say, “Hi.” You can look them in the eye, talk to them, and ask how they’re doing, realizing it’s an individual. Maybe there’s something you can do to help, like get them a sandwich or a cup of coffee.

Anything else?

Just to keep an eye on these young men and women when they come back. If you know one, maybe you can help them with their transition into normal life, because normal life is just so, so incredibly different and hard after what they have been through.