Diebenkorn first saw Matisse’s work at the Palo Alto, California, home of collector Sarah Stein, who was also Gertrude Stein’s sister-in-law. He was stunned by Matisse’s color and technique, and how the master’s canvasses displayed his process.

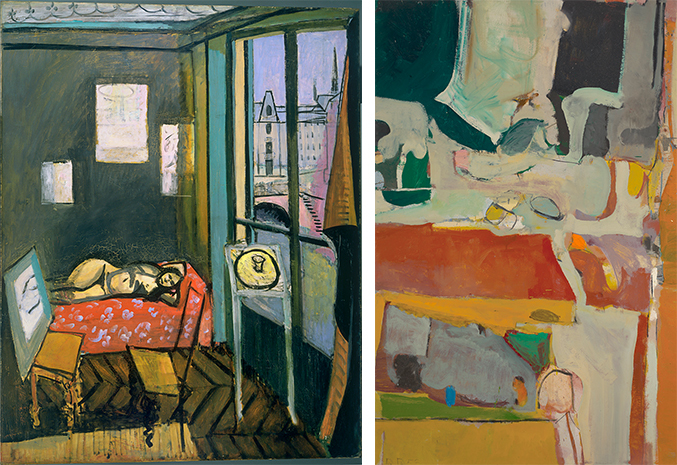

Matisse “shows you how he painted his works,” says Rothkopf, like in the 1916 work Studio, Quai Saint-Michel, which Diebenkorn would have seen when he visited what is now The Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. The bold lines that define the room shows the viewer how Matisse structured his canvas and balanced the scene inside the room from the imagery outside the window and door.

Diebenkorn would use a similar color palette and canvas structure in his 1953 work Urbana #4, which showcases the more Abstract Expressionist style he’d adopted at that point. At the time, he’d taken a teaching position in Urbana, Illinois, and found the landscape so bleak that he blacked out all his windows so he could revel in the lush paints on his canvas.

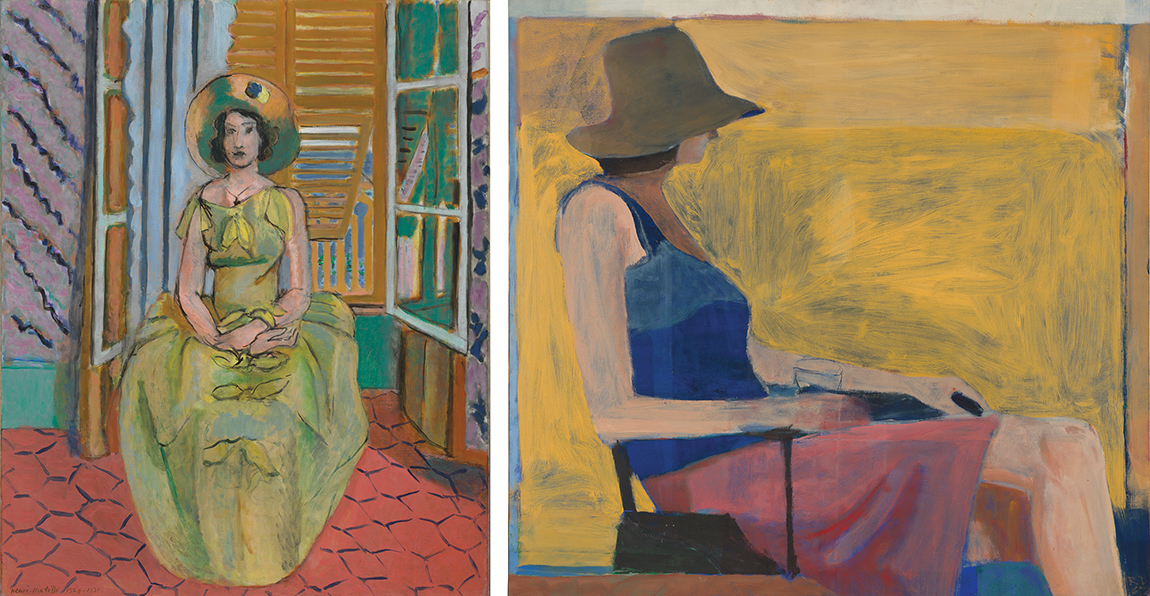

In 1966, Diebenkorn attended a major Matisse retrospective, which included more than 300 works by the artist, who had died 12 years before. Among the paintings displayed was this work, The Yellow Dress, which is a part of the Cone collection at the BMA.

A year later, Diebenkorn produced Seated Figure With Hat, which in a way is his own version of Matisse’s own seated woman. He uses a similar color palette, with vibrant yellows and orangey reds, but puts his own twist on his model, who happens to be his wife, Phyllis, as he angled her away from the viewer. Unlike Matisse, “Diebenkorn wasn’t as interested in facial features,” Rothkopf says, instead choosing to focus on more of the feeling the figure’s placement gave to the painting.

This would be one of the last of Diebenkorn’s figurative paintings. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, his work again began to change.

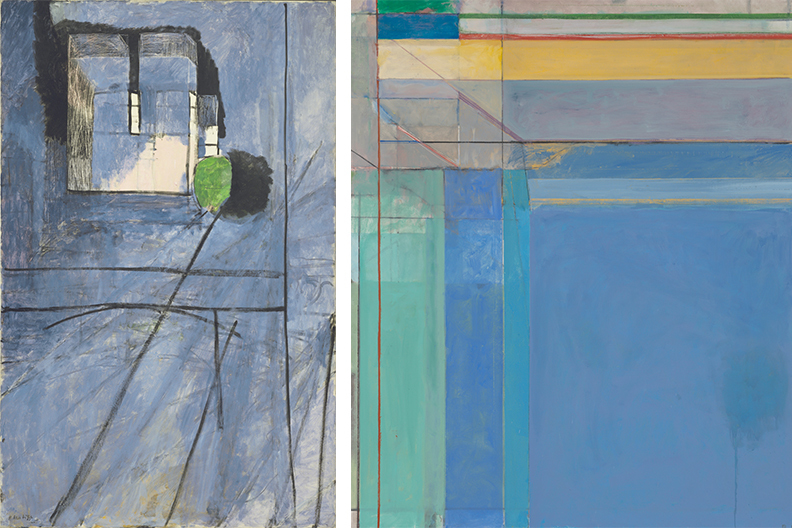

Diebenkorn is perhaps most celebrated for his Ocean Park series, a group of paintings named for his studio locations in southern California. Ocean Park #79 from 1975 shows how much his work has reverted back to abstraction. But instead of the heavy, textured brush strokes of his early career, these paintings are geometric and serene, with lines that give the work an altar or window-like structure.

Matisse’s View of Notre Dame has a similar linear composition, and the less-detailed form of Notre Dame seemingly appears through a window. This 1914 work came at a time when Matisse was the most experimental. “Diebenkorn thought this was his most interesting period,” Rothkopf says.

Diebenkorn would continue in this direction until his death in 1993, and this painting by Matisse continued to serve as inspiration. “There are three paintings that come up repeatedly for Diebenkorn—this is one of them.”

This Sunday, the BMA is holding an opening celebration for Matisse/Diebenkorn, with reduced adult admission, free admission for those 18 and under, as well as a host of activities, including gallery tours and a talk by Diebenkorn’s daughter. Click here for more information.