The Oscars used to be but one day, Hollywood’s grandest and most singular moment to shine. Now we have this thing called the Oscar “season” (although even that term is a bit of a misnomer, as it goes on all year long). Oscar season goes into overdrive right about now, with various pundits speculating about which films are Oscar contenders (ranking the films much the way we rank teams in college sports) and various pre-Oscar award shows and critics’ Top 10 lists rolling in—all providing clues as to how a film might stack up on that big day. Early award shows, like the Critics’ Choice (of which I am a voting member) like to boast that they are the greatest prognosticator of the Oscars. The mysterious Hollywood Film Awards—which aired on network TV and was well-attended by celebs, despite the fact that no one was quite sure what it was—proudly trumpeted that they were the first awards show of the “season.”

It’s a bizarre intersection of art and competition, and everyone who does it feels slightly sullied by the whole endeavor, including myself. (Every time I write in a review, “It’s an Oscar-worthy” performance, I’m playing the game. I just can’t help myself.)

But here’s the real problem: Oscar pundits aren’t applying a traditional critical standard to their rankings. They’re not necessarily looking for the best films. What they’re looking to do is make a correct prediction (the more correctly they predict, the more valuable their sites become). So they focus on “Oscar bait”: i.e., a film with a big enough studio, a big enough budget, big enough stars, and just enough of a message to make the Oscar voters feel that they’ve chosen something worthy. (I wrote about what makes the perfect Oscar film here.)

The Oscar prognosticators are predicting—but they’re also starting the conversation, creating the parameters. Oscar voters in turn read these prognosticators and are influenced by them. So you get this kind of house of mirrors, with Oscar voters being swayed by prognosticators who are trying to second guess the voters.

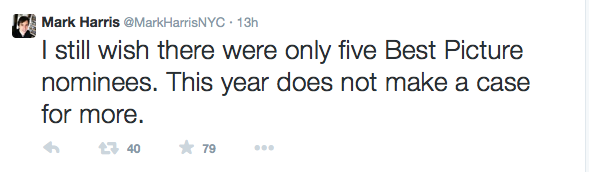

Then, last night, Mark Harris, a cultural critic and Oscar expert that I happen to admire a lot, tweeted this:

It definitely made me scratch my head. I’m in the middle of cramming in as many awards screeners as possible in preparation for my own voting and end of the year list. I already have a working “Best of the Year” list that includes 20 titles—and there are several reportedly great films I have yet to see (including The Imitation Game, Selma, and Mr. Turner).

So what exactly is Mark talking about here?

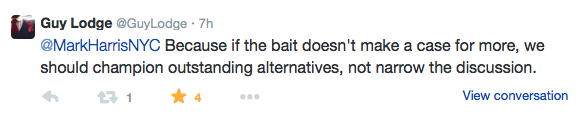

I think Guy Lodge, the film critic for Variety and The Guardian, perfectly expressed my befuddlement with his follow up tweets to Mark:

The truth is, all critics and industry observers are guilty of liking a film, but giving up on it, seeing it as a lost Oscar cause. But why? Why must we cleave to this idea that certain kinds of films are Oscar worthy, while others are not?

As I look over my list of the best films of the year, there are already several titles that I love, but I assume aren’t “Oscar bait”:

Force Majeure – Swedish, too grim

Nightcrawler – too darkly satiric and violent

The Babadook – a horror film, which makes it almost impossible to get nominated; plus made on a shoe-string budget in Australia

We are the Best – again, a Swedish film, this one dealing with two young girls who start a punk band—not a grand enough subject for Oscar

Love is Strange – a wise and wonderfully observed film about an aging gay couple who gets married—probably considered too slight for Oscar

Beyond the Lights – wildly entertaining, but it’s a backstage melodrama—again, not “important” enough for Oscar

Ida – stark, black and white film about a nun in post World War II Poland who discovers she’s Jewish. (Polish + black and white + nun basically make this one a non-starter)

Obvious Child– a hip and charming comedy about abortion. Enough said.

Dear White People – satire about black students at an Ivy League college. The film has no major backing and the subject, of course, is considered too incendiary for Oscar.

Snowpiercer – hella cool dystopian sci-fi about a caste system on a train. (Oscar hates science fiction.)

All of these films are wonderful. Many focus on marginalized groups—young women, gay men, African-Americans, Polish nuns (heh). And not one has a real shot at being nominated for Best Picture.

So what is the solution to this? I think those of us who are critics—and that includes myself— should stop getting in the Oscar prediction game, at least not until the eve of the awards, when all the votes have already been tallied. We are merely stoking the status quo. And maybe, those who are starting the conversation about Oscar—the prognosticators like Awards Daily and The Carpetbagger and Gold Derby—should expand to at least include these more marginalized films, if not as outright predictions, then as “wish lists”.

Bottom line. There were way more than five great movies this year. But I agree with Mark. There may not have been more than five great “Oscar” films.