Arts & Culture

The Walters Unveils Landmark Reinstallation of its Asian and Islamic Collection

The exhibition brings together diverse regions and religious and artistic practices in a sweeping show that highlights their interaction and influence upon one another.

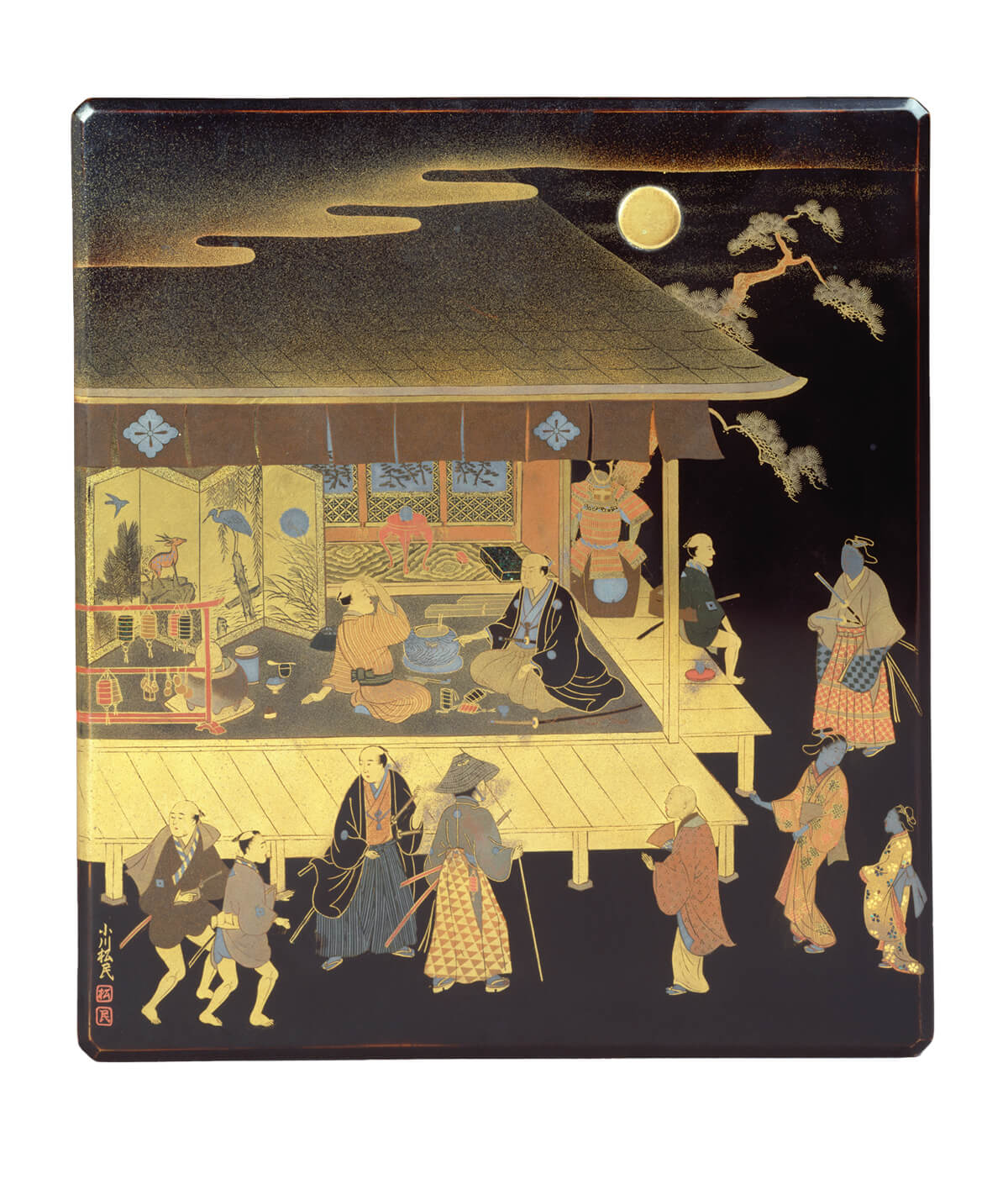

The Walters Art Museum’s stunning collection of Asian art spans some 5,000 years and 900 works, stretching across Japan, Korea, and China to India, Nepal, Tibet, Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia. The Walters is also home to one of the richest collections of Islamic art in the U.S., comprising 1,200 objects mostly from Persian, Turkish, and Mediterranean cultures, as well as Islamic South Asia.

With an opportunity presented by a restoration of the Hackerman House, the previous home to much of its Asian and Islamic collection, along with a reexamination of the museum’s longtime centering of its European work, the Walters recently unveiled a landmark reinstallation of its Asian and Islamic collection that encompasses the museum’s entire fourth floor.

Led by Adriana Proser, the Walter’s chief curator of Asian Art, Dany Chan, the museum’s associate curator of Asian Art, and guest curator Ashley Dimmig, a former postdoctoral curatorial fellow in Islamic Art, the exhibition brings together diverse regions and religious and artistic practices in a sweeping show that highlights their interaction and influence upon one another.

Notably, visitors will also encounter a Japanese digital animation of nature and a mixed media meditation piece from MICA graduate Lingling Lu, pointing to the ongoing influence of Asian art in the West.

We recently caught up with Proser to discuss the reimagining process, curation of the exhibit, and some of her favorite works.

I went to see the new exhibition late one afternoon and was so enthralled by it that the guards eventually said, “We’re getting ready to close, you’re welcome to come back tomorrow. We open at 10 a.m.” And I did. I came back the next day.

Well, that’s great. You know that warms a curator’s heart.

This new installation of the Asian and Islamic collections was years in the making. Can you describe the reimagining process a bit?

When I came for my interview [three-plus years ago, from New York’s Asian Society], they were already talking about the project and about this idea of movement of artworks across cultures and between Asian countries and Islamic countries, and also, beyond that, with places in Europe and Africa.

That’s it. It’s that the movement within the installation across geography and eras that is enlightening and rewarding. It also feels natural and seamless. Not at all like you’re just moving from one object, painting, or sculpture to the next.

I think what made this project unique and successful was that. From the get-go, we were trying to make sure that, as much as possible, we were looking at the various components of the project as a whole.

The inclusion of local voices from the Muslim community and the Asian community was also an inspired idea. It adds a dimension to the exhibition and fits in seamlessly as well.

I want to put together narratives that make sense and don’t feel awkward. I also think that we were able to find members of the community, like the head monk from the Silver Spring Thai Buddhist temple and Aisha Imam from Reed Society for the Sacred Arts, who helped us do that.

This installation also feels like part of the museum’s reexamination of its collection, how it’s presented, and general effort to be more inclusive.

Definitely, and I think it’s going to feel even stronger when the new Ancient Americas gallery is open in a couple of years. We’re deliberately trying to make the non-Western cultures not seem like they’re add-ons or afterthoughts, but really have a museum that is presenting its collections on equal footing because they also reflect the heritage and cultures of so many different Americans. And again, it’s by putting these things from many cultures in proximity to each other that we can recognize and highlight how long all of our cultures have been engaging with, interacting with, and sometimes even influencing each other.

I realize this may be an impossible question. Do you have a favorite work?

Oh, my goodness. You know, all my geese are swans, right? The thing that really seems to make the installation special is the thammat [the Buddhist pulpit from Thailand]. It was clearly made for a temple with royal sponsorship. It’s very, very elaborate and it also kind of encapsulates what we’re trying to do it. It’s this combination of a 19th-century object that has elements that show ties to China, like the wood carving in it. Probably a lot of the craftsmen who worked on it originated in China and then emigrated to Thailand. But it has very unique qualities of Thai art, too. It’s such a striking, glittering presence and yet it also gives us an opportunity to tie its architecture to other objects in the collection in a way that we never could before.