News & Community

Road to Ruin

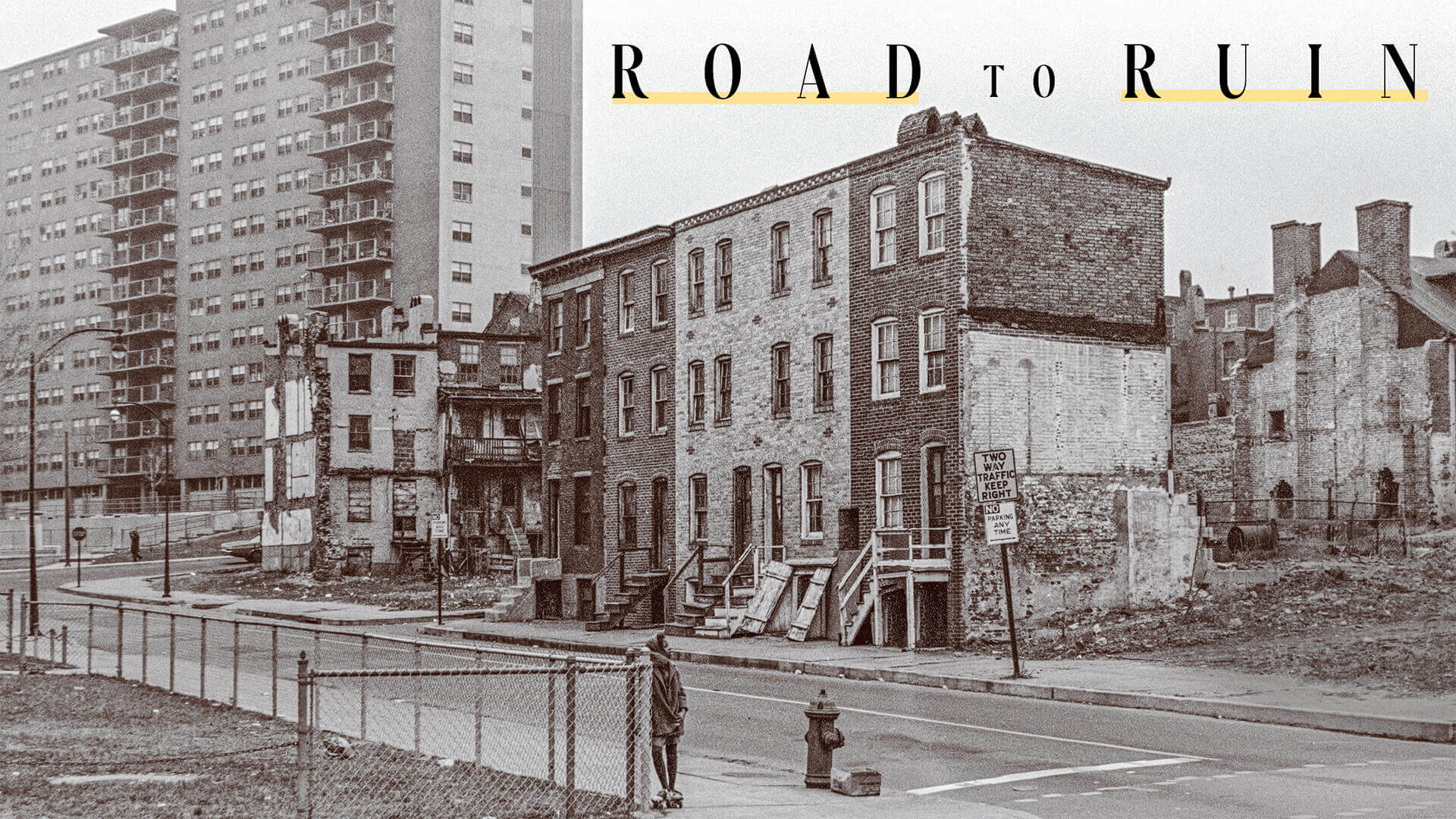

In the late 1960s, Baltimore began demolishing Black neighborhoods to make room for an ill-fated expressway. Will the harm from the Highway to Nowhere ever be repaired?

By Ron Cassie

Photography by Isaiah Winters

Historical images by John Van Horn and I. Henry Phillips

Opening Spread

The image of the forlorn girl on the

outskirts of the Highway to Nowhere was shot by John Van Horn

in the fall of 1968 (see sidebar at the end of the piece). JOHN VAN HORN

CLOSED THE CAR DOOR and stepped onto the sidewalk in front of his childhood home when he recognized an old friend coming toward him. “Chubb!” Smith called out with a big smile. It was right before Christmas and the two men, both in their mid-70s, began reminiscing about growing up in the Rosemont neighborhood, specifically the Lauretta Avenue blocks around the Smith family’s corner rowhouse.

“‘Fort Lauretta,’ that was the Smith house,” says Laneaue Burch, explaining that everything and everyone had a nickname in the close-knit West Baltimore community. (“I got ‘Chubb’ because I was skinny.”) “This is where we gathered and played football. I caught a lot of passes in this street and that empty lot,” he continues, gesturing across the intersection. “This time of the year, we’d be pulling out our new footballs and roller skates—those metal skates you snapped over your shoes. Skating in the streets was big. Oh man, we had fun.”

Ironically, a sign on the corner now reads: “No Ballplaying in the Street,” though few kids appear to live or play here anymore.

Their neighborhood had everything a family needed in the 1950s and 1960s, says Smith, one of eight children raised by his father, grandmother, and a half-dozen “block moms” after his mother died. “This wasn’t the food desert it became. There were corner stores and grocery stores, clothing, furniture, and hardware stores, bakeries, pharmacies—mostly Black- or Jewish-owned—and movie houses, like the Harlem Theater at Edmondson and Harlem, the Bridge Theater at Edmondson and Pulaski,” he says, ticking off two favorite Saturday hangouts. “I tell people it was a Norman Rockwell existence.”

Then, in 1969, two years after Smith graduated from Edmondson High, the city informed his family that their home stood in the path of a planned expressway, and they intended to demolish it. Originally named I-170 (later re-designated Route 40), it was supposed to connect the booming white suburbs to Baltimore’s downtown business district. It certainly wasn’t conceived to assist Black commuters. The Franklin and Mulberry streets corridor had first been identified in 1944 by consultant and notorious New York highway builder Robert Moses as the path of least resistance—in other words, low income and Black. Neither Smith’s father, a crane operator, nor Burch’s father, who cooked at a white country club, owned a car. Before the expressway, the city had a dependable transit system: streetcars, and then buses, that reached Black neighborhoods.

Glenn Smith sits on the steps of his childhood home on Lauretta Avenue in Rosemont.

“What choice did he have? My father took the money offered and moved to Windsor Hills,” recalls Smith, glancing down the hill to the near-empty east-west expressway, or rather the 1.39-mile stub, since known as the Highway to Nowhere because it never got connected to I-70, I-95, I-83, or any other major road. “Then, he had to get a car. My youngest siblings moved with him. I joined the Marines and the rest went on their own. I don’t think my father, who’d come to Baltimore from North Carolina after he got out of the Navy, ever adjusted.”

The dismantling of corridor neighborhoods had begun shortly before the 1968 riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.—and ramped up after them. Ultimately, 971 homes, 62 businesses, and one school were leveled, and more than 2,800 people were displaced. On Lauretta Avenue and elsewhere, almost everyone Smith and Burch knew—whether homeowners, tenants, or “rent-to-own” families—were forced out. It is a cruel twist that Fort Lauretta was spared and resold by the city after construction began in 1974. (Burch’s aunt was one person who did not sell, however, and her Lauretta Avenue home was spared as well. Burch eventually took over her home after she passed.)

For decades, Smith and Burch will tell you, their beloved neighborhood has been a literal shell of what it was. Despite knocking down 130 vacant homes and buildings in recent years, the city still has 373 vacant building notices posted in the community. Next door in Harlem Park, which took the brunt of the expressway’s wrecking ball, there are 570. Long stretches on the Franklin Square and Poppleton side of the Highway to Nowhere—less than a half mile from the Edgar Allan Poe House Museum—have also been shuttered for decades, although a driver coming in from Baltimore County can’t really see the boarded-up neighborhood from the expressway’s voluminous concrete valley, also referred to as “the Ditch.” Planners intended to provide commuters with a “pleasant view” of the city skyline on their approach into town.

“You know a funny thing that I notice when I come back to our old house?” Smith says, pointing to the side of the Lauretta Avenue rowhome. “The Formstone. I remember when my father had that put up. Not a mark on it. Still perfectly intact.”

The Highway to Nowhere, taken from a drone in October. —Video by Isaiah Winters

From top, women on Palm Sunday in the late 1950s in Lafayette Square, a few blocks from the Highway to Nowhere; a young girl in Lafayette Park, also in the late 1950s. I. HENRY PHILLIPS

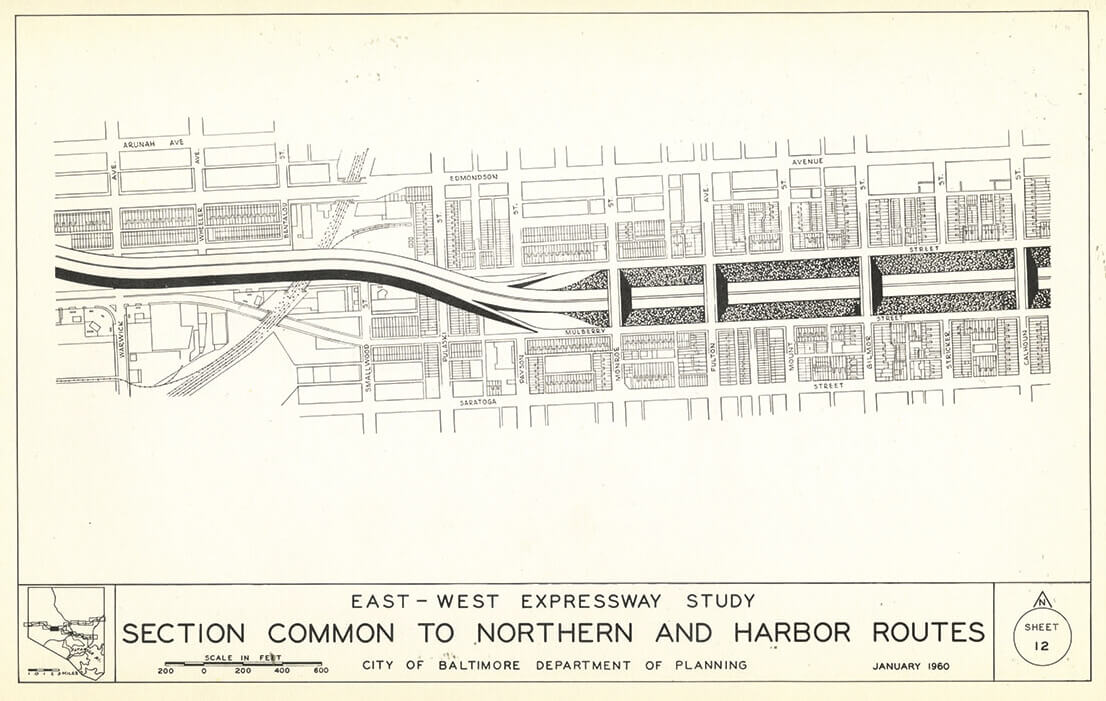

A 1960 rendering of the planned expressway through West Baltimore.

I n his acclaimed book on blockbusting and the redlining of Black communities, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City, former Baltimore Sun reporter Antero Pietila estimates that roughly 94,000 people—mostly Black residents—were dislocated between 1965 and 1980 by various expressway building, “slum clearance,” and “urban renewal” efforts. Many affected families had come to Baltimore looking for jobs after World War II, as part of the Great Migration, and now they were uprooted again. Payouts offered to homeowners in the Franklin-Mulberry corridor—based on declining “fair market” values in the area—were rarely enough to purchase a comparable house in one of the few neighborhoods open to Black homebuyers. (Future Hall of Famer Frank Robinson and his family struggled mightily to find a home after he was traded to Baltimore in 1966; his wife Barbara was so disgusted by the race-based real-estate market she threatened to move back to California with the couple’s two children.)

“Monuments to segregation,” ACLU lawyer Barbara Samuels called the high-rises, all since imploded as failed housing policy experiments.

Meanwhile, the destruction in the neighborhoods split by the Highway to Nowhere metastasized. The east-west expressway plans had cast a pall over the Franklin-Mulberry corridor for two decades, and when the condemnations began in 1966, and then the demolitions a few years later, things quickly took a bad turn. By the time the highway opened on Feb. 5, 1979, the surrounding blocks—and their communities—had been gutted for a decade.

Today, residents in the Black neighborhoods divided by Route 40 have the longest average commute times in Baltimore, almost three times greater than in the city’s well-to-do white neighborhoods.

“The effects of that little underpass didn’t just go into the 300 or 500 block [of a street in its corridor],” Alton West, who later organized annual reunions among those displaced, told an interviewer back in 2009. “It just spread its wings either way. Call it the ‘domino effect’ or whatever you want...[things] just fell and kept going. If the 400 block was affected, now the 3 and the 5 are . . . and after a while the 600 or the 100 [block]. I would say by the mid-’70s to the late ’70s, it was like the spread of cancer. It was just inoperable.”

As far as strategies to rehabilitate the community after the fact, added West, a retired Baltimore housing inspector, “I say ‘we’ as a city government—we just probably didn’t have a clue.”

The 1870-built Sarah Ann Street rowhomes formerly scheduled for demolition by the city.

N ow, a half century after it consumed 52 acres of residential Black neighborhoods—and eight years after the Red Line light rail was abruptly canceled by a governor intent on building more highways—there are hopes that the Highway to Nowhere may finally be razed.

Passed in August, the Inflation Reduction Act, which allocates $370 billion to address climate change, includes $3 billion in Neighborhood Access and Equity Grants that can be used to reduce the effects of urban heat islands, for example, but also to remove harmful infrastructure, such as urban expressways.

The side-by-side Carrollton Avenue rowhomes owned by Sonia and Curtis Eaddy, who successfully fought the city’s eminent domain plans for 18 years.

That funding comes a year after the federal government set aside $1 billion in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act for the Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program, which was modeled off legislation co-sponsored by Maryland senators Ben Cardin and Chris Van Hollen—with the Highway to Nowhere in mind. In October, the city applied for a $2-million grant through the program to study tearing up the ill-fated highway. Recipients should be announced this spring.

“Baltimore is the poster child for this program, which is designed to right a historic injustice the federal government helped facilitate,” says Van Hollen, who, along with West Baltimore-raised Congressman Kweisi Mfume, drafted a letter on behalf of the state’s Democratic congressional delegation to U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, urging consideration of the city’s bid. “I bring this up to Secretary Buttigieg every time I see him,” says Van Hollen. “He probably wants to turn in the other direction when he sees me.”

At the same time, the state has a newly elected governor from Baltimore. Wes Moore, the first Black governor since the 1632 founding of the Maryland colony and just the third-ever elected in the U.S., has vowed to jump-start the 14-mile, 19-stop Red Line light rail initiative. As previously designed, it would have passed directly through the long under-resourced Highway to Nowhere corridor.

With proposed stops at the West Baltimore MARC station—in Rosemont, Harlem Park, and Poppleton, neighborhoods where up to 60 percent of households don’t own a car—the anticipated light rail promised reliable access to employment, the Social Security office complex in Baltimore County, the University of Maryland, the downtown business district and the Inner Harbor, as well as the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center. It meant access to schools, grocery stores, healthcare, recreation, and entertainment.

The construction of the Red Line—pitched to help repair a half-century- and-counting of damage from the Highway to Nowhere—was six months from putting out bids when former Governor Larry Hogan canceled it without a single formal review in 2015. The building of the project alone was expected to create 15,000 direct and indirect jobs. The Maryland Transit Administration was already working with the state’s Department of Labor to create a training program tailored for engineering, construction, and maintenance positions at Glenn Smith’s old high school.

Today, any attempt to bring the now dust-covered Red Line plans back to life faces enormous hurdles. The original price tag of $2.9 billion, which included $900 million in attached federal funding, has climbed significantly with inflation. Federal transit funding remains hyper-competitive, and winning back approval any time soon is hard to imagine. (When Hogan sent that nearly $1 billion back to the feds, he also flushed away a dozen years and $290 million in local and state planning.)

Federal dollars also require a commitment from the state, which will likely have to foot at least two-thirds of the project again. Former Governor Martin O’Malley increased the gas tax to generate revenue for the Red Line, but that money is gone. How Moore intends to raise funding remains to be seen. Not to mention, recent residential and commercial developments in Canton and Greektown will require new engineering work-arounds. Environmental studies will have to be repeated. Community outreach, always a contentious process to some degree, will have to begin again.

While both Moore and Mayor Brandon Scott are committed to bringing down the Highway to Nowhere—by no means a sure thing given the funding necessary—the bigger question is: What should, or will, come in its place?

Will Moore and Scott fight for a full light rail plan like the one Hogan canceled and has the potential to create the greatest economic impact? Or will they settle for a less expensive—but more doable—rapid bus version of the Red Line? In an interview, Scott said he’s committed to an east-west light rail system while acknowledging a rapid bus line may ultimately play a role. The removal of the Highway to Nowhere and the once shovelready light rail—linked by purpose and overlapping geography—remain separate initiatives until Moore and Scott decide on a common vision.

Former Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John Porcari was on the ground floor when the ironically named Red Line (“redlining” traditionally referred to mortgage discrimination against Black home buyers) was first conceived 20 years ago, in large part to address systemic racism in transportion exacerbated by the focus on building highways to accommodate automobile drivers. He says that even with equity and environmental justice as a priority at the DOT under Buttigieg, funding for transit and expressway removal remains exponentially harder to win than highway-building dollars. That said, the availability of Biden infrastructure money and Reconnecting Community grants, according to Porcari, “presents a unique opportunity that is not going to last forever. The city and state need to get their plans together and act quickly.”

To Red Line advocates such as Samuel Jordan, a longtime community- based organizer, the stakes could not be higher.

Mayor Brandon Scott, with the Highway to Nowhere behind him, and elected officials, including U.S. Senator Chris Van Hollen and Congressman Kweisi Mfume on his right.

Jordan co-founded the Baltimore Transit Equity Coalition with Glenn Smith after the project was canceled by Hogan. In December, the organization commemorated the 66th anniversary of the end of the Montgomery bus boycott with a webinar update on its Red Line and transit equity efforts.

“Frankly, this is a social justice and civil rights struggle,” says Jordan, 74. With Smith and two others, Jordan filed a federal civil rights suit against the Hogan administration, as did the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. A transportation economist using the state’s own models, “found that whites will receive 228 percent of the net benefit from [Hogan’s] decision, while African Americans will receive -124 percent.” (The Obama Administration decided the NAACP case merited an investigation, but that inquiry was dropped by former President Trump’s Department of Justice without comment.) Jordan emphasizes that at the same time Rosa Parks, Claudette Colvin, and others were refusing to surrender their seats in Alabama, Baltimore’s politicians and business community were planning to demolish Black neighborhoods for an expressway to serve white automobile drivers.

“The racial equity struggle is more than just being able to sit wherever you want on the bus,” he says. “What about the quality of the service itself? What about the racial disparity of transportation and transit spending? That’s what our coalition seeks to eliminate. We want to put a halt to, and address, the structural racism that has always been central in public transit policy and that got us here.”

A view of the Highway to Nowhere from a bridge above the 1.39-mile expressway.

R emarkably, Baltimore’s urban expressway system, which also includes I-395 and crash-prone I-83, could’ve been much worse. The concept of a cross-town expressway was first studied by local engineers hired in 1942. Baltimore passed the baton two years later to the aforementioned Moses, and the New York highway builder’s subsequent report originally called for displacing not the 2,800 residents eventually resettled, but an estimated 19,000 people. The sprawling plan, tweaked a dozen times over the ensuing decades, was initially intended to link an east-west expressway to Route 1 and Route 40, roads leading to Philadelphia and Washington. Bulldozing Black neighborhoods was not the most controversial part at the outset; it was plowing just south of The Walters Art Museum and the Washington Monument in Mount Vernon to connect to the Orleans Street viaduct and Route 40.

In fact, the bulldozing of low-income, minority neighborhoods to alleviate congestion for white automobile drivers was sold as a feature, not a bug. Moses, who interestingly never learned to drive, did not understand that neighborhoods in older cities like New York and Baltimore were like small towns or villages onto themselves. Ambitious, arrogant, and particularly unconcerned with Black and brown communities, he anticipated and dismissed citizen opposition in Baltimore as he did in New York.

“Some of the slum areas through which the Franklin Avenue Expressway passes are a disgrace to the community and the more of them that are wiped out, the healthier Baltimore will be in the long run,” Moses wrote in his Baltimore Arterial Report, the basis of which laid the foundation for the Highway to Nowhere route. “Nothing which we propose to remove will constitute any loss to Baltimore.”

Robert Caro, who covered Moses as a young reporter and then profiled him in the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography, The Power Broker, characterized Moses as “one of the most racist men” he’d ever encountered.

Citizen outrage against the Moses plan was immediate, with some 1,500 people filling an auditorium for a city council hearing on the proposal in early 1945. Sun columnist H.L. Mencken called the Moses plan “a completely idiotic undertaking.” And a member of the traffic committee that hired Moses said the plan “poses a mountain of human misery.” Yet, Baltimore’s civic and business elite pushed ahead.

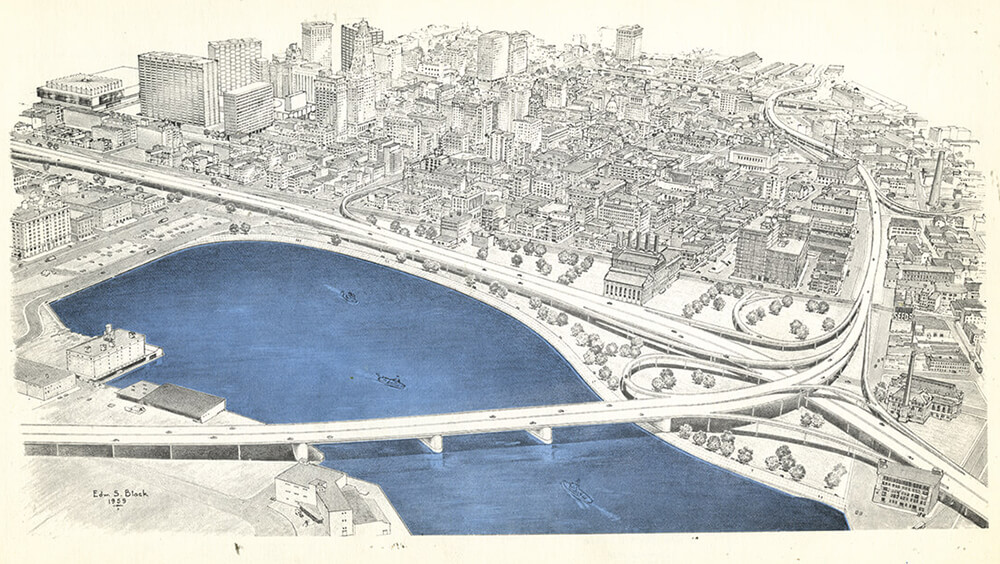

A well-orchestrated protest by a bohemian collection of artists, artisans, and LGBTQ community members on a single, colorful block of Tyson Street rowhouses—described as Baltimore’s mini-version of Greenwich Village—helped quash the Mount Vernon thruway. In its place, however, city planners in 1959 came up with an equally crazy scheme. The new plans called for taking the Franklin-Mulberry expressway south to intersect with I-95 and I-83, which were in the works, along with the Baltimore Beltway. Everything was to culminate (see rendering) in an overpass 40 feet above the Inner Harbor and a 14-lane interchange where Harbor East now sits. That expressway proposal would have ripped through Gwynns Falls-Leakin Park, the middle-class Black neighborhood of Rosemont, the Franklin-Mulberry corridor, Sharp-Leadenhall in South Baltimore—a one-time abolitionist hub established by freed slaves—before lopping of the top of Federal Hill and crossing over the Inner Harbor.

A great deal of Fells Point, written off by many as a white working-class slum, was marked for the scrap heap, which famously launched a then-social worker from the area named Barbara Mikulski into action. And if you now reside in Federal Hill, Fells Point, Canton, or Harbor East—or simply enjoy the Inner Harbor, Rash Field, and the bars and restaurants along the city’s unique sevenmile waterfront promenade—you have Mikulski and a scrappy group of activists to thank. Born from the democratic idealism of the 1960s, highway protestors formed grassroots organizations with feisty names like M.A.D. (Movement Against Destruction), a cross-city, biracial coalition of 35 neighborhood groups; R.A.M. (Relocation Action Movement); and S.C.A.R. (Southeast Council Against the Road).

“They would rather run the expressway through Black folks’ bedrooms than a white folks cemetery,” was a popular R.A.M. slogan aimed at a plan to knock down homes in Rosemont to avoid Western Cemetery. Together, they organized one of the most successful, though not perfect, highway revolts in the country. “We had maybe eight people when we started,” recalls the 86-year-old Mikulski, referring to S.C.A.R. “We met almost every night of the week in some bar or church basement to make it look like we had a lot of support.”

In 1967, the inaugural Fells Point Fun Festival was organized to raise funds for anti-highway legal efforts. Two years later at the annual street party, which continues to this day, a then-33- year-old Mikulski shouted her opposition as then-Council President William Donald Schaefer, a big expressway proponent, tried to speak. “The British couldn’t take Fells Point, the termites couldn’t take Fells Point,” railed Mikulski, who would soon win her own seat on the City Council. “And we don’t think the State Roads Commission can take Fells Point either.”

Paradoxically, as the federal government was doling out billions for expressway expansion—funding 90 cents on the dollar for highway projects—it eventually passed legislation that would also prove a boon to local anti-highway activists.

The Federal Aid to Highways Act and The National Historic Preservation Act, both passed in 1966, had provisions to protect natural habitat, park and recreation land, and historic buildings. Those laws became vehicles for activists to delay the Leakin Park, Federal Hill, and Fells Point sections of the broader expressway system plans in court. Preservationists got Fells Point placed on the National Register of Historic Places in early 1969. Federal Hill won the designation a year later. Both neighborhoods, then and now majority-white, would ultimately be saved.

“The national highway system was truly a great American achievement, that was Eisenhower’s plan,” Mikulski says. “However, the Robert Moses approach, his vision destroyed neighborhoods so he could create other neighborhoods.”

Several cities Mikulski is referencing—New York, Boston, San Francisco, Oakland, Milwaukee, Chattanooga, Providence—have already converted urban expressways to more neighborhood-friendly boulevards. Others are in process.

The tragedy is the city’s long effort to link the east-west expressway to I-70, I-95, and I-83 was all but dead by 1974, when then-Mayor Schaefer gave the final go-ahead to build the now pointless 1.39-mile spur. Relatedly, Schaefer’s and city leaders’ obsession with building highways through the city is the reason Baltimore doesn’t have a full Metro system like Washington, D.C., which did not have a thriving downtown like today when planning began for that project in 1967.

“It was well beyond the time when a reasonable person would have said, ‘Wait, it’s time to reevaluate,’” says Evans Paull, a former city planner and author of Stop the Road: Stories from the Trenches of Baltimore’s Road War. (See our full interview with Paull, here.) “[He] was also a very strong pro-business guy, and the Greater Baltimore Committee was the No. 1 cheerleader behind the highway plan. . . . The irony is that if the city business interests advocating for highways had been successful, it would’ve been economically disastrous for the city. The later redevelopment of all those [Inner Harbor] neighborhoods might not have happened if the highways been built.

“I also don’t think the city would have ever entertained an expressway through a comfortable middle-class white neighborhood, the way it did Rosemont, for example,” continues Paull. “I think it’s just characteristic of the city’s low regard for African- American neighborhoods that it was the only section that got built in the end.”

To his point, just this summer, after an 18-year battle with the city, Sonia and Curtis Eaddy saved their rowhome, which sits a block south of the Highway to Nowhere, from demolition. The city first sent a condemnation notice to the Eaddys back in 2004, along with more than 100 of their Poppleton neighbors, including dozens of homeowners. Baltimore officials had decided to clear out the neighborhood for a University of Maryland expansion and a New York-based company’s proposed development.

The Eaddys’ struggle was part of a broader successful community campaign to preserve a small block of distinct 19th-century rowhouses around the corner from their home on Sarah Ann Street. Unfortunately, those residents were all forced to leave before the homes were finally designated offlimits and safe from development. Only a few, if any, are likely able to return.

“My dad grew up in this block,” says the 57-yearold Sonia Eaddy. “He was at 329 Carrollton Avenue and I’m 319. He bought his house in 1969 or 1970, and that’s where I grew up. ‘The Highway’ was up the corner. My grandmother and grandfather moved to the 1200 block of Mulberry, across the street, so as a kid, I remember when the city demolished their property. I remember the gravel, the metal poles with the wire surrounding the blocks that were demolished. We used to play on those lots and throw rocks. Then when they started to dig, you had to take what we called ‘the bridge’ across to see friends, go to school or church, or go to Edmondson Avenue, which had a lot of shops.

“I was young, I can’t speak directly to how people felt about the city condemning their property at the time,” she continues, “but with our home and the Sarah Ann Street homes, it was basically like, ‘You don’t count. You don’t matter.’”

There are also historical echoes between the building of the Highway to Nowhere and the cancellation of the Red Line.

Just two months before King’s assassination and the riots in Baltimore, Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III—in an address to the American Road Builders Association, no less—acknowledged the dark truth that the planned expressway, “will displace thousands of families, will dismember neighborhoods and communities, will disrupt industry and commerce, and will destroy parks and historical landmarks.” The Little Italy native, whose father had been mayor when the east-west expressway plans were first hatched, added that “the problem of dislocation of people is particularly critical.” He even forewarned the dislocations would become “a major cause of unrest.”

Nonetheless, as Paull highlights in his book, only two weeks after the riots, D’Alesandro decided to stick with the final expressway design that would devastate the Franklin-Mulberry corridor.

In an analogous gut-punch to a reeling West Baltimore, Governor Hogan announced his decision to defund the Red Line two months after the uprising following Freddie Gray’s death. At the same time, he said he would increase infrastructure spending on roads and bridges by $1.35 billion—“from Western Maryland to the Eastern Shore.”

At a 2015 news conference, Hogan defended, at least in part, his decision this way: “We just spent $14 million extra money on the riots in Baltimore City a few weeks ago.”

Thirty years earlier, in the mid-1980s, Schaefer, on the cusp of running for governor, approved a deal that sent $261 million of the last of the unused city-expressway funding back to the state. Part of that money was used for an I-68 project in Western Maryland. History, as they say, may not repeat, but it often rhymes.

Rowhouses in the Franklin-Mulberry streets corridor, which the city had acquired, being demolished in 1968 to make room for the Highway to Nowhere. John Van Horn

I n hindsight, it is amazing how quickly the automobile transformed American culture and transportation planning. From 1945 to 1965, car ownership doubled in the U.S., outpacing vehicle ownership rates in Europe by a sometimes 4-to-1 margin. Americans still drive twice as many per capita miles as Europeans.

A 1959 rendering of the planned 14-lane interchange that was designed to connect the future east-west expressway with I-95 and I-83.

In Baltimore and elsewhere, the automobile age was not just driven by the Federal-Aid Highway act of 1956, which funded 41,000 miles of new highways over the next decade—then the largest public works project in American history. It had been hastened a decade earlier by the orchestrated collapse of streetcar and trolley systems.

Baltimore, where the first commercially operated electric streetcar had been put into use in 1895, boasted one of the densest networks. Routes ran all through downtown and to the Catonsville, Towson, and Dundalk suburbs, among others, knitting the metro region together. It was the invention of the streetcar that first led to the development of the suburbs.

Gas and tires had been rationed during World War II, a period when reliance on transit use peaked in Baltimore. After the war, National City Lines took over the privately owned and operated Baltimore Transit Company in 1945, and purposely began tipping the scales—in favor of cars and the combustible engine. It sounds like a conspiracy theory, but National City Lines was in fact a holding company owned by General Motors, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California, and Phillips Petroleum. It acquired streetcar operations across the country, then began systematically replacing the Baltimore streetcars with GM-built buses and Firestone tires, which of course also ran on Standard Oil and Phillips Petroleum. They disinvested in maintenance, cut back service, and started dismantling streetcars, which often carried more than 100 people. Ridership dropped dramatically year over year. You can see where this is going.

The major east-west line streetcar line, the No. 15, ran along Edmondson Avenue, through the heart of West Baltimore, and almost parallel to what replaced it, the Highway to Nowhere.

National City Lines wasn’t only to blame, however. City officials and business leaders wanted the streetcars gone to make room downtown for cars, especially after work began on the modernist Charles Center. Expressways and automobiles, they were convinced, were the future. Unfortunately, so was the air pollution that disportionately affected Black communities and the public health consequences of leaded gasoline, particularly for children living near highways. The last two electric streetcar routes, the No. 15 and No. 8, which ran to Towson, were converted into bus lines in November 1963.

In other words, the concept behind the east-west Red Line light rail is not new. In 2015, projections estimated the project would stimulate $4.6 billion in development along the route, with particular hopes of sparking transit-oriented development around the Poppleton, Harlem Park, Rosemont, and West Baltimore MARC stations.

“Public transportation, good or bad, is the connective tissue between everything else, whether that’s climate change, or employment, economic development, and education—issues we know that also underlie poverty and crime,” says Baltimore City state delegate Robbyn Lewis, who, in 2011, as a community organizer founded the grassroots Red Line Now PAC to lobby for the project. “I won’t forget a Johns Hopkins study a couple of years ago that linked [the Maryland Transit Administration] bus system waiting times for Baltimore students to absenteeism, which is chronic in the city. After a certain age, kids in the city can go to any school they want to, if they get accepted. But the bus system, which is run by the state, is underfunded and unreliable. So, kids are late to school. I met a mother in Brooklyn whose child had been accepted at City College high school, a tremendous opportunity. She just didn’t know how they were going to get there.”

Or to put it more plainly: “There is just no separating housing and transportation policy from white supremacy and structural racism,” says Lewis, acknowledging pushback from some residents in white-majority Canton against the Red Line when it was initially planned.

Given its density, the width of Boston Street, and the fact it has the highest rate of automobile commuters in the city, Canton would seem like an ideal location for public transit. More recently, a “Save Suburbia” campaign has begun in Baltimore County amid discussions to build a city/county light rail in the York Road corridor. Sixty years ago, white residents in Anne Arundel County blocked a planned extension of the Baltimore Metro subway, deriding it as the “loot rail.” “We need a light rail system, and we need more buses, and more bus drivers,” Lewis says. “We need it all.”

One of many stretches along the Highway to Nowhere that suffered in its aftermath.

L ike Glenn Smith, who ministers with a local faith community and now lives in a senior apartment building a dozen blocks away from his childhood rowhouse, Denise Griffin Johnson grew up in the Franklin-Mulberry corridor.

Her parents separated when she was young, but her father rented a home within walking distance to remain close to the children. He lived on Franklin Street, the one-way parallel to Mulberry Street, until he was forced to relocate for the Highway to Nowhere.

Community advocate Denise Griffin Johnson, who grew up next to the Highway to Nowhere, in front of the Arch Social Club, whose previous location was demolished for the expressway.

Johnson’s parents had migrated from Mississippi to Baltimore after her father returned home from World War II and heard about jobs at Bethlehem Steel open to Black workers. (One Black veteran spoke up in a City Council hearing related to condemnation of the neighborhood, saying that he’d fought in the war to save his country, only to have to fight his country to save his home.)

“We used to go to Lexington Market together,” recalls Johnson, now 64. “One of the things I remember is when he had to move after condemnation, he couldn’t take his dog to his new house. It really bothered him. He asked my mom to take it, but she had seven of us to take care of.”

A family counselor by profession and community volunteer by practice, Johnson co-founded Culture-Works in 2007 with artist Ashley Milburn, whose graduate Community Arts thesis at the Maryland Institute College of Art focused on the Highway to Nowhere. Four years later, they brought an annual “Roots Fest” conference and arts festival to the same neighborhood.

“There had never been a public discussion by the former residents who were displaced about what happened,” Milburn told the City Paper at the time. “I attended a meeting during my first internship at Bon Secours, and this one woman in her 80s stood up and was talking about rampant crime and all this stuff, and then she got on to the Highway to Nowhere, because she said, ‘It used to be different.’ I turned around and looked at her and she was crying. And I looked at other people’s faces and they had this empathy, there was something here.” Baltimore artist and performer Sheila Gaskins later wrote and directed a well-received play, Last House Standing, based on Milburn’s research.

That sadness still exists for many of the older community members, says Johnson. “The fact that this story continues to be told and written about, you’d like to think there is the possibility at some point, to tell a different story about what is occurring in the space to benefit West Baltimore.”

She notes the walking paths, trees, benches, and exercise equipment that have been added to the grassy knolls alongside the Highway to Nowhere in recent years. But also that decades of promises have failed to transform the 1.39-mile concrete desert.

In 1997, former Mayor Kurt Schmoke and his housing chief pitched the idea of tearing up the road, filling in “the Ditch,” and creating affordable homes that would once again connect Poppleton and Franklin Square on one side with Harlem Park and Rosemont on the other. “[The expressway spur] was a great mistake, and we were thinking of ways to correct it—the money just wasn’t there,” says Schmoke today. “When it was built, the federal government was funding 90 percent of the cost. By the time I became mayor, it was more like a 50-50 split, and let’s just say removal projects were not the priority.”

In 2010, Governor O’Malley and then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake touted a $2.5-million project to remove a small, elevated piece of the Highway to Nowhere as a gamechanger. Headlines hyped it, too. One read “Highway to Nowhere heads to the dump,” but it merely replaced a short section with two additional MARC parking lots. No subsequent development ensued.

For his part, Smith won’t be satisfied with any plan that isn’t light rail. Even well-intentioned proposals like the razing of the Highway to Nowhere, a rapid-bus version of the Red Line, more green space, or the possibility of affordable homes in the corridor, would still be a wasted opportunity, he says. They won't do enough.

In terms of frequency, on-time dependability, and the ability to move lots of people quickly, he doesn’t believe light rail can be matched by rapid bus service. Transit-oriented development traditionally follows rail, he notes, which when built attracts investment because of its permanence. New bus lines, according to standard planning thinking, don’t spur economic development; they follow it.

“No other project than the light rail will bring relief and healing to the devastation we’ve been through,” he says. “The impact must be equal to the destruction.”

Destruction of a Neighborhood: Baltimore's Highway to Nowhere

The black and white photographs of the demolition of the Franklin-Mulberry corridor that accompany this story were captured by then-college student John Van Horn. Now 72, Van Horn recently self-published a collection of those photos. This is his memory of the images:

“In the fall of 1968, I was a freshman at Western Maryland College, now McDaniel College. I was a history major, but my passion was photography. As I was driven into Baltimore on Route 40 by my college friend Larry Sanders to go to a photography store, we went through this neighborhood being demolished. I returned on my own via a bus ride and a second time with Larry to photograph the area.

I recall most vividly the series I took on my own when I took the bus into Baltimore one early Saturday morning. I was from a small town in New Jersey, photographing a poor inner-city neighborhood. This was 1968, a year of political and racial violence and unrest, with the Vietnam War always in the background. However, the deserted neighborhood was just that, deserted. I only saw a couple of children at play, which I photographed, but don’t recall any interaction with them or any of the few adults I encountered beyond perhaps a ‘good morning.’

The initial reaction, that this destruction would be interesting to photograph, soon turned into thinking of what a waste this was. I was looking at rows of iconic Baltimore rowhouses being destroyed . . . probably a large part of some people’s identity. I saw the destruction of a neighborhood, the homes, and the businesses. The photos looked like images of a war zone, like those of Europe during WWII and today from Ukraine. The big difference is, war damage can be rebuilt and residents return; here, it was final. These photos still bring up deep feelings about injustices brought upon people who had little or no voice in their destinies. Every time I look at them, I have strong emotions. It is still hard to decompress those emotions after 50 years."