Food & Drink

A Rolling Revolution

Food trucks adapt to a changing world during the pandemic.

Willy Dely, a hospitality consultant who organizes the annual Maryland Food Truck Week, was worried as he watched mobile vendors struggle during the early days of the coronavirus pandemic, when all their revenue sources disappeared—from the lucrative lunch trade in a city on lockdown to area festivals and catering gigs. Then, he had a light-bulb moment. Why not bring the food trucks to the Baltimore County neighborhood where he lives?

Starting last May, trucks like Chesapeake Food Works, Jimmy’s Famous Seafood, and Gypsy Queen began parking their kitchens on wheels in the 9000 block of Seven Courts Drive in Perry Hall. Now, trucks are scheduled there an average of four times a week.

“It’s a good thing for everyone,” says Dely, owner of Au Jus Solutions. “The customers benefit. It gets people out of their houses. And it’s a good opportunity for the food trucks. It grows their followings.”

The response was so enthusiastic in Perry Hall that, in December, Dely set up another location for food trucks in Dundalk. He works with Dough Boy Fresh Pretzel Co., which hosts the trucks on its 7458 German Hill Road property, and also sells its stuffed pretzel bites and other nibbles alongside the vendors. But Perry Hall and Dundalk aren’t the only communities hosting food trucks. They can be found in several counties and many locations on a rotating basis.

Ericka Weber was excited when one of her neighbors brought a Baltimore Crab Cake Company food truck to her Loch Raven Village neighborhood in Towson.

“I really liked that truck,” Weber says. “I thought, ‘Can we do other trucks?’”

She soon became the de-facto organizer for inviting food trucks like B’More Greek Grill, Wanna Pizza This, and Stony Man Coffee & Donuts to the Village. She arranged to use the parking lot at Babcock Presbyterian Church on Loch Raven Boulevard.

“I reach out to the trucks, and they contact me as well,” says Weber, a social worker and mother of two who lines up food trucks several times a week. “They’re really nice people. Everyone has been so gracious.”

She plans her family’s meals around the food trucks’ visits. “I went to all of them originally,” she says. “Now, I decide which ones togo to and how many we can afford.”

Dely is relieved that the food trucks are finding a way to keep busy. “We could have used more food trucks this year. What if this is the new normal?” he asks. “The trend is strong for some neighborhoods.”

If you want a food truck to come to your neighborhood, you can reach out to them. Most have a Facebook or website presence with contact information. Here, five local food trucks share their experiences.

→ Kooper’s Chowhound Burger Wagon

Kooper’s Chowhound Burger Wagon is the granddaddy of Baltimore’s food-truck brigade. Founded in 2009 by Patrick Russell and his wife, Katie, it’s an offshoot of the Russells’ Kooper’s Tavern in Fells Point.

The first mustard-and-cocoa-colored truck was an immediate hit with its plump, gourmet burgers nestled in soft brioche buns. Soon, there were two trucks roaming the streets, feeding business communities at midday and turning out mounds of beef patties at festivals and corporate events.

The trucks took a detour last March as COVID-19 shuttered restaurants, and people were cloistered in their homes. “The pandemic had an interesting effect,” Patrick Russell says. “We noticed that people wanted food trucks to come to the neighborhoods where they live.”

Early on, one of the trucks was parked at Kooper’s North in Timonium, drawing hungry customers and “did really well,” says Samantha Hofherr, director of operations for the three Kooper’s restaurants (another one is in Jacksonville) and the Russells’ other eateries, Woody’s Cantina and Slainte Irish Pub and Restaurant in Fells Point.

Before long, the two trucks were branching out to other areas, including Hunt Valley, Catonsville, and Howard County. “We’re going places we’ve never gone before,” says Hofherr. “People wanted to support the trucks.”

Harry Sheesley and his wife, Kathleen, are fans. The retired couple discovered Kooper’s Chowhound at Babcock Presbyterian Church in Towson. “It’s the best burger we’ve ever had,” says Harry, who favors Chowhound’s Elvis Got the Blues burger, a pileup of juicy beef, applewood smoked bacon, and blue cheese. “It really helped. We were tired of eating indoors.”

While the Elvis may be Sheesley’s go-to burger, Hofherr says other top patties include the MacGuinness, similar to the Elvis but with cheddar cheese; the Baja, with slaw and Jack and cheddar cheeses wrapped in a flour tortilla; and a lamb burger with feta on a rosemary focaccia. The food trucks “have really kept the business afloat,” Hofherr says.

Owner Patrick Russell also found another way to keep his staff working—feeding the homeless. Through donations, the trucks have been able to serve food to people at Baltimore’s tent communities, including the one under the JFX bridge near East Centre Street. On one visit, the truck dished out chili and cheeseburgers to 50 people.

“You wouldn’t believe the kindness people show,” Russell said of the contributions he’s received. “I’ve been able to keep people employed and feed the poor. I’m just the vehicle. This is how we’re making it work.”

→ Craving Potato Factory

In the beginning of the pandemic, Courtney “C.J.” Jacobs and his wife, Monique “Mo” Jacobs, had six catering gigs canceled, leaving them and their food truck Craving Potato Factory with nowhere to go. But the setback didn’t stall the mobile business, open since 2014, that sells all manner of stuffed potatoes. “We had to create our own events,” Mo says.

Today, the couple—who have three children, ages 17, 13, and 10, who help out on the sleek, black kitchen on wheels—has found a market for their spuds in neighborhoods like Towson and the White Marsh-Middle River area. “It’s been great,” says C.J., who grills aromatic toppings like onions, red peppers, and steak on the truck’s stove.

And while everything is cooked to order, Mo and C.J., who both have full-time jobs with the federal government—she as a management analyst and he as a customer representative—are often up at 4 a.m. to prep foods in Share Kitchen, a communal space in Baltimore. They go through about 250 potatoes a week.

“It took time to perfect the potato,” C.J. says. “We use the best ingredients we can.” Even winter’s cold weather wasn’t a deterrent to their community outreach. “I’m find- ing food trucks can occur in all seasons,” says Mo, who, on a chilly, icy evening, had her children deliver food from the truck to customers snuggled in their warm cars.

The food truck started as a nugget of an idea between C.J. and his brother, Shawn Hill. First, they thought about featuring fried chicken and then empanadas before deciding on gourmet potatoes.

“You have to have a concept, something different that no one else is doing,” C.J. says. Mo was involved in the decision-making, too. When Hill returned to his hometown, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands, C.J. and Mo, who are also from the Caribbean territory, forged on together.

They introduced four loaded potatoes: chicken bacon ranch, broccoli and cheese, steak with grilled onions and peppers, and Old Bay lump crab. They now offer a vegan one with tofu and have expanded the menu to include a “dirty bird” potato with two meats.

Picture plate-sized, creamy baked potatoes split open and smothered with melted cheeses and savory additions. You’re guaranteed to have leftovers for the next day’s lunch.

“We want to give people what they want,” says C.J., whose goal is to eventually open brick-and-mortar restaurants. “We want the whole world to get a taste of our potatoes.”

→ Stony Man Coffee & Donuts

After working as a bartender in pubs like The Hideaway in Odenton and The Brass Tap in Annapolis, Brooks Parce was ready to do something different in the culinary field. “I worked in restaurants my whole life,” he says. “It’s all I know.”

So he and his wife, Shanell, started Stony Man Coffee & Donuts food truck, brewing their first cup of coffee in 2019 with beans from Open Seas Coffee Roaster in Stevensville. “We love working together,” he says. “We wanted to do our own thing.”

The couple, who have been married for eight years and have two children, ages 6 and 2, are hopping on a national trend showing a demand for breakfast food trucks. The morning hours suit the life-work balance they are trying to achieve, Parce says.

When the pandemic hit, “we didn’t know what direction to go in,” he says. Then, they discovered an interest for their coffee shop on wheels in suburban communities. You’ll now find the roving Stony Man in Perry Hall, Towson, Pasadena, Severna Park, and other places.

“We love the neighborhoods,” Parce says. “Meeting people at the [food-truck] window is fun for me.”

Parce was a latecomer to coffee drinking. He didn’t take a sip of the brew until he was in his 30s, urged by his coffee-loving wife. He was hooked. “I have an obsessive personality,” he says with a laugh. “I read everything I could about coffee.”

When the time came, he was ready to share his new passion with customers in a bright-orange truck that also sells boxes of 15 gussied-up doughnut holes to complement the coffee. These are not your plain-Jane doughnuts.

Flavors include Boston cream, bananas Foster, Old Bay caramel, hot honey, and two of the most popular offerings: chocolate madness, topped with Oreo bites, chocolate pudding, chocolate sauce, and chocolate sprinkles; and French toast, glistening with a maple vanilla glaze. They are served hot and fresh. “Who doesn’t love the combo?” Parce says. “You can’t beat it.”

If you’re not a coffee drinker, the Parces have you covered with beverages such as hot chocolate, cold and hot teas, hot apple cider, and flavored lemonade. The menu also includes cold coffee brews.

As new business owners, Brooks and Shanell Parce are still figuring out what their customers want. “We’re looking to learn,” Brooks says. “We’ll keep expanding.”

→ The Smoking Swine

Like many of his food-truck compatriots, L. Drew Pumphrey hit the brakes on his mobile kitchen, The Smoking Swine, when the pandemic hit last spring. His downtown Baltimore lunch business disappeared as people worked from home and festivals folded. He also wasn’t able to open his restaurant on Hanover Street in the Brooklyn section of the city that was scheduled for April 2020. But it will happen, he promises, maybe as soon as 25 percent dining-room capacity is allowed.

Still, Pumphrey has managed to hang on for now. “We are limping along,” he says, thanks to area communities asking him to bring his traditional American barbecue to them. Now, he’s on the road four to six days a week to serve up his smoked ribs, chicken, and delectable “Slap Yo’ Mama” mac and cheese throughout Baltimore, Howard, and Anne Arundel counties. “We are going to where the money is,” he says. “We’re out a lot more, but we also have less business.”

Ironically, Pumphrey made the decision to add a second food truck last year and is glad he did. He needs it for the increased travel, he says.

Pumphrey still gets a lot of attention from his appearance on Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives in 2016, especially when the Food Network episode is rerun. “It changed the way I did business,” he says, noting he had to adjust to more customers and media attention. “It was the first time I’ve been in the national spotlight.”

Not bad for the former appliance repairman who hated his job but loved smoking meats and spent a year and a half planning the food truck he introduced in 2012.

Pumphrey predicts that food-truck operations will change after COVID, though he’s not exactly sure what will happen. “I don’t see how it could be the way it used to be,” he says. “The industry will be fundamentally different.”

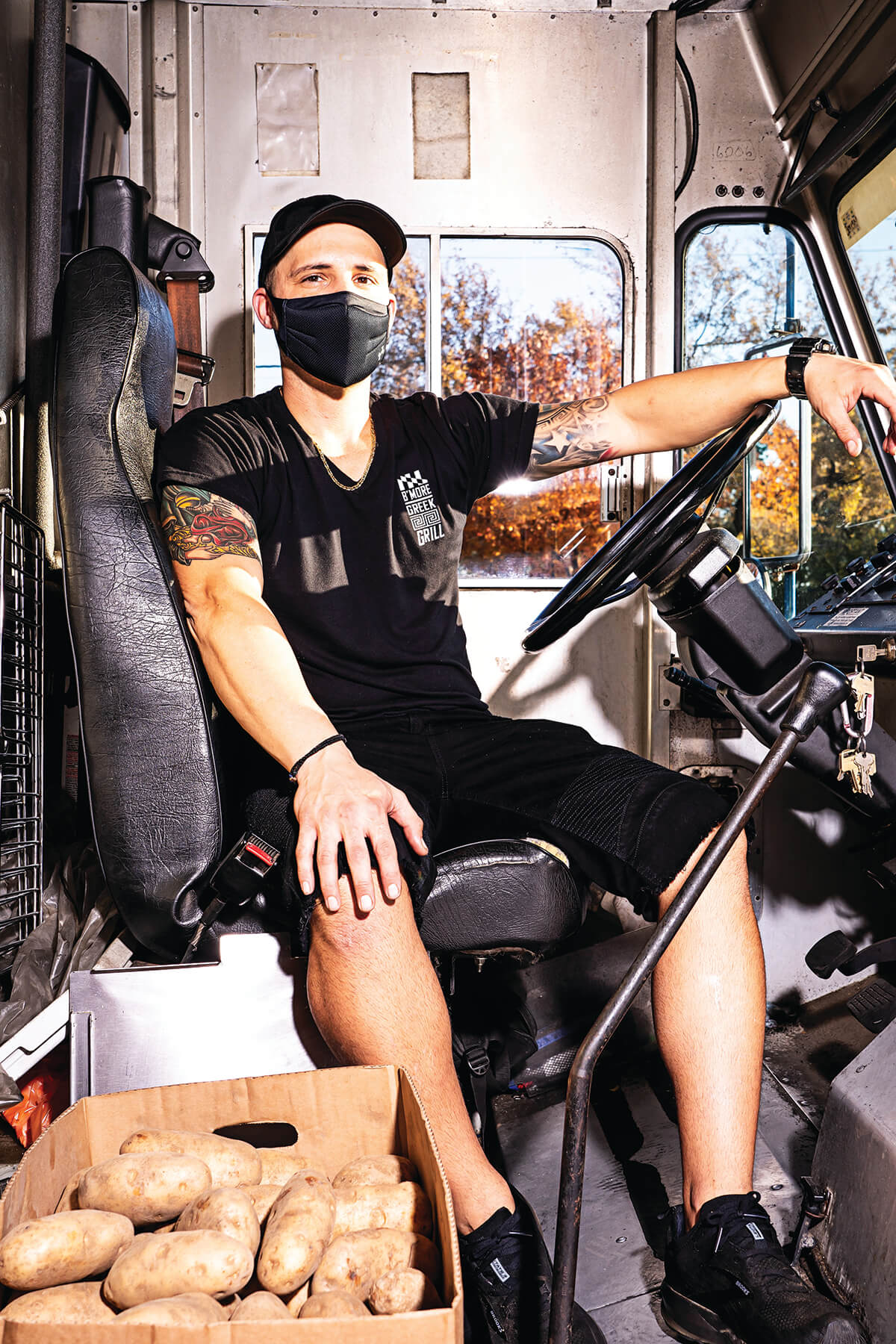

→ B’More Greek Grill

Pantelis “Pete” Bakoulas, who oversees the three B’More Greek Grill food trucks, is proud of his roots.

“We’re just a little Greek family from Greektown,” he says. “We wanted to open a carryout restaurant but didn’t have a lot of resources. We started a food truck as a steppingstone.”

That was in 2015. Bakoulas focuses on his family’s treasured recipes. His parents, Andreas and Anthia Bakoulas, emigrated from Greece almost 40 years ago, but continued to make the dishes that nurtured them in their homeland.

The B’More trucks, painted as deep blue as the Aegean Sea, are turning out authentic Greek food with some twists, like their popular cheesesteak pita wrap and French fries with feta cheese, Bakoulas says.

Think traditional gyros with tender lamb, soft pita bread, platters bursting with grilled meats and rice topped with “Mama’s sauce,” a secret creamy blend, according to Bakoulas, and Greek salads with the family’s homemade dressing, a lush olive-oil mix with a hint of sweetness. “It’s a huge hit for us,” Bakoulas says of the condiment. “We’re looking to bottle it.”

Then, the pandemic dealt a blow to their growing business. Seemingly overnight, the corporate accounts with companies like Exelon Corp. and business from universities like Loyola and Johns Hopkins dried up and outdoor festivals were scrapped. “It’s been difficult,” Bakoulas says. “We had to restructure.”

The mobile kitchens pivoted to serving the staffs of hospitals like Johns Hopkins and MedStar Franklin Square Medical Center, and then the neighborhoods came calling.

“Most of the residents didn’t have a lot of food options,” says Bakoulas, referring to restaurants’ closures and limited capacities during COVID. “It’s a good thing we’ve been able to visit different areas.”

On various days, you’ll find the trucks in Perry Hall, White Marsh, and Hunt Valley, among other locations. “It feels like they’re family,” says Ericka Weber, who arranges for B’More Greek Grill to come to Babcock Presbyterian Church in Towson on a regular basis. Even on a recent bitter winter evening, a crowd showed up.

Bakoulas looks back to earlier last year when he almost settled on a permanent spot in Federal Hill. “With the coronavirus, it’s a blessing we didn’t open,” he says. “Fortunately, we stuck with the trucks.”

He’s not sure what the future holds for his business. “I wish we had a crystal ball,” he says. “My family didn’t want to give up. We’re going to do what we’re doing as long as we can.”