Damian Mosley and Linwood Dame

Two local chefs talk about cooking, food trends, and biscuits.

By Jane Marion

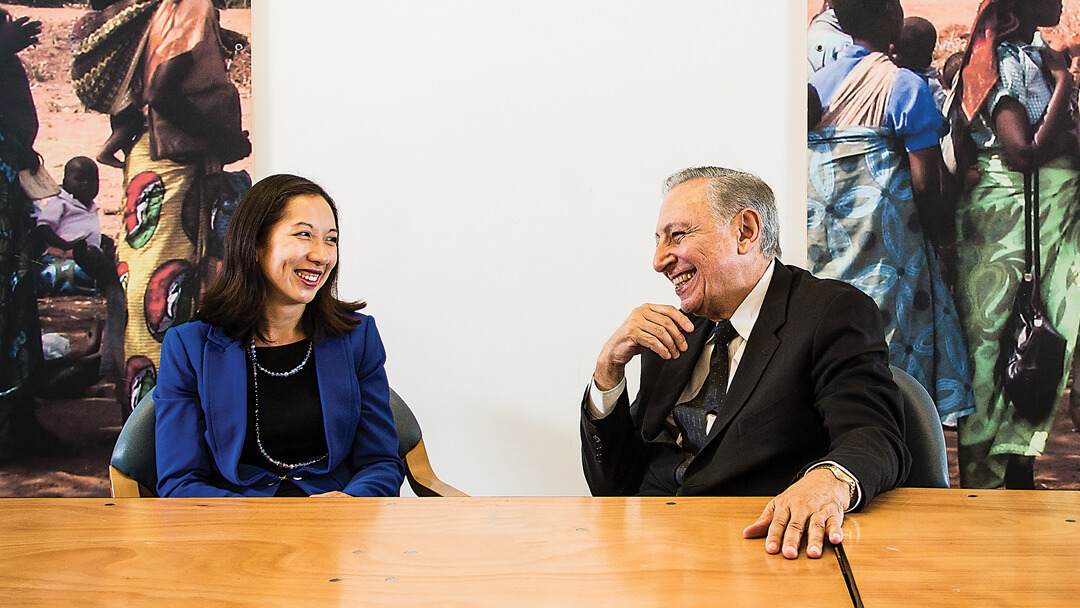

Mosley, left, and Dame talk biscuits at Linwoods in May. —Photography by Justin Tsucalas

Linwood Dame, owner/chef of Linwoods is a fine-dining fixture in Owings Mills, while Damian Mosley, owner/chef of Blacksauce Kitchen, is making a name for himself with catering work and handmade biscuit sandwiches sold at the Baltimore Farmers’ Market and local festivals. Though they’d never met, the duo hit it off at a May 18 dinner over a bowl of shrimp and grits (for Damian) and goat-cheese ravioli in brown butter with asparagus (for Linwood) at Linwoods.

Linwood Dame: Were you out there under the bridge [at the Baltimore Farmers’ Market] yesterday?

Damian Mosley: We were.

LD: We were going to try to get down there under I-83 to eat some biscuits. I didn’t realize that you’re out there so early in the morning. How many people come down there at a time?

DM: On a normal Sunday, we probably serve four to five hundred. We probably make about 600 biscuits every Sunday. We start at two in the morning.

LD: You start baking biscuits at two in the morning? Being in the restaurant business, you don’t realize that a business like that does those kinds of numbers on a Sunday morning at the farmers’ market.

DM: The toughest thing for a small squad like us is that we catered an event on Saturday night.

LD: So you turn around and you’re back at it again after a few hours of sleep. You do that all the way through October?

DM: All the way through December.

LD: Are you from Baltimore?

DM: I grew up in Virginia.

LD: I grew up in the South, but I’ve lived in New Jersey, Tallahassee, Atlanta, North Carolina, Virginia, and Chicago.

DM: How long have you been in Baltimore?

LD: We’ve been here 27 years. I had a restaurant and catering business in Richmond. That’s how [my wife] Ellen and I met. We were thinking about going to D.C., but it was ’86 or ’87 at the time and we realized that Baltimore didn’t have anything. There was Tio Pepe, The Prime Rib, Danny’s, and a lot of old-school restaurants, but that was a period when things were starting to change in this country. At the same time, open kitchens were very, very new.

DM: What made you decide you wanted an open kitchen then?

LD: They were very popular and they were opening them in California. I got the idea from there. It was all about French food back then. In the late ’70s, things really started to change. American cuisine really started to take over.

“Food has gotten so much better in this country, We’re better educated; we care more.”

DM: The momentum changes so much in terms of a particular kind of cuisine or style of cooking. To have one establishment stay open for that long seems incredible to me.

LD: One of the challenges is having to go along with the changes. Food has gotten so much better in this country. We’re better educated; we care more. The people who work for me today are so different than the people who worked for me 20 years ago. When I got into this business, there wasn’t a lot of respect for servers, there wasn’t a lot of respect for chefs, and it’s really changed. So, how did you get into this?

DM: My parents are from Mississippi. My maternal grandmother lived on a farm and baked cakes for a couple of local businesses. In 1969, my father started working for the USDA. He was inspecting meat for food-stamp programs. My mom was working for the McDonald’s Corporation. She worked at Hamburger University in Chicago and then, when we moved to Virginia, she worked in their franchising department. I don’t think I realized how closely connected my parents were to food when I was growing up. My first summer in college, I went to work for a law firm in D.C. I went back to school and started working in a restaurant in North Carolina. I did a little bit of cooking and prep.

LD: So that was it?

DM: I just remember how much it felt like a family to work there. When I came out of school and did a couple of stints in law firms, it didn’t seem like I was doing anything unique or valuable. I always loved writing, so I moved to Philadelphia to try freelance writing, but I also enrolled at cooking school. My very first semester, it was like magic.

LD: Why biscuits?

DM: I ended up going to grad school at New York University to study what then was a one-of-a-kind food studies program where we talked about food history, food systems, food and culture, food and race. I started teaching a class at a community college in Brooklyn—those students had different needs. Many had worked the previous night. If what I was talking about wasn’t interesting, they weren’t going to stay awake. I would bake biscuits for the class. I had students from Poland and Russia and Jamaica, but they all loved to eat biscuits. Years later, in Baltimore, I realized that biscuits were an everyman’s food. If I was going to make one thing, it was going to be biscuits, so I took them to the farmers’ markets and people loved them. I also think I chose them as a little bit of a nod to Mississippi—my mom made biscuits in my house when I was growing up, and when she was growing up, she made biscuits every day.

LD: When I was growing up, our family never went out to dinner—there were just too many kids. We had dinner at home, and most times we had someone else at the table—friends of our brothers and sisters. Food would be lined up—roasted chickens, mashed potatoes, green beans. We were always around a lot of food. . . . How do you create?

DM: I don’t always think about the process, because it feels very natural to me.

LD: Every Friday we have a chef’s meeting and it’s also a tasting meeting. Is it sweet? Is it salty? Is it crunchy? It is sour? I’m driving to work in the morning and that’s what I’m thinking about. It’s a very emotional business in that regard. If you have a passion for it, it’s not just a job.

-

Kwame Kwei-Armah & Lawrence Gilliard Jr.

-

Reverend Donté L. Hickman Sr. & David Warnock

-

David Simon & Laura Lippman

-

Dr. Leana Wen & Dr. Robert C. Gallo

-

Denise Koch & Stan Stovall

-

Josh Charles & Derek Waters

-

José Antonio Bowen & Shanaysha Sauls

-

Laurie DeYoung & Konan

-

D. Watkins & Clarence M. Mitchell IV

-

Gaia & Doreen Bolger

-

Deb Tillett & John Davis

-

A Conversation with Dan Deacon

-

The Burning Question

-