Food & Drink

Living Proof

America’s first whiskey was born in Maryland. Centuries later, it strives for a historic comeback in Baltimore.

By Lydia Woolever

Photography by J.M. Giordano

and tin awnings of the post-war houses along Sollers Point Road—a lone, brick smokestack, rising above the electric lines along the overgrown railroad tracks, towering over the last, long-vacant factories left standing in Dundalk, a stone’s throw from the Port of Baltimore and Francis Scott Key Bridge.

From a closer distance, perhaps along Distillery Avenue in the newly developed Foundry Station, where construction is underway on future townhomes, it emerges in full scale, its size signifying what must have once stood here, and from the tippy top of the rust-red chimney—still almost perfectly intact—three words come into focus: Baltimore Pure Rye.

It’s hard to envision now, as decay plumes across its neighboring water tower, but there was a time, not that long ago, when an entire state-of-the-art factory town once stretched out beneath its shadow, and back then, a series of large brick buildings bustled with dozens if not hundreds of workers, producing a form of whiskey that had put Baltimore, and Maryland, on the national map.

“Born with a future,” hailed one nearly full-page advertisement for the Baltimore Pure Rye Distilling Company in a 1938 Sun, heralding their first, four-year-old, straight rye whiskey, released almost half a decade after the end of Prohibition, when the city’s centuries-old spirits industry came to a sudden and shattering halt. Now, finally—as the short, square, one-quart bottle seemed to declare—whiskey makers would capture that lost momentum, with companies like this one sprouting up out of the embers to sate the thirsty throngs once again.

Even in the midst of the Great Depression, B.P.R., as would later appear on its labels, was no modest distillery. At the time, it was touted as the largest independent rye whiskey operation in the entire United States, with bushels and bushels of its namesake grain arriving by the truckload to this 12-acre property, prized for its proximity to “artesian water” along the Patapsco River.

Here, under master distiller William E. Kricker, some 9,000 gallons of rye whiskey were meticulously produced across two shifts each day, then aged in white-oak barrels inside a six-story, temperature-controlled warehouse, before being bottled and sold to high-end establishments—to be remembered fondly by tony tipplers for decades to come. “Some people around the country are making so-called whiskey with a quick process,” Kricker told The Sun in ’38. “Here in Baltimore, we follow the proven old-time way, and so far, we are having good luck with it.” Of course, that wouldn’t last forever either.

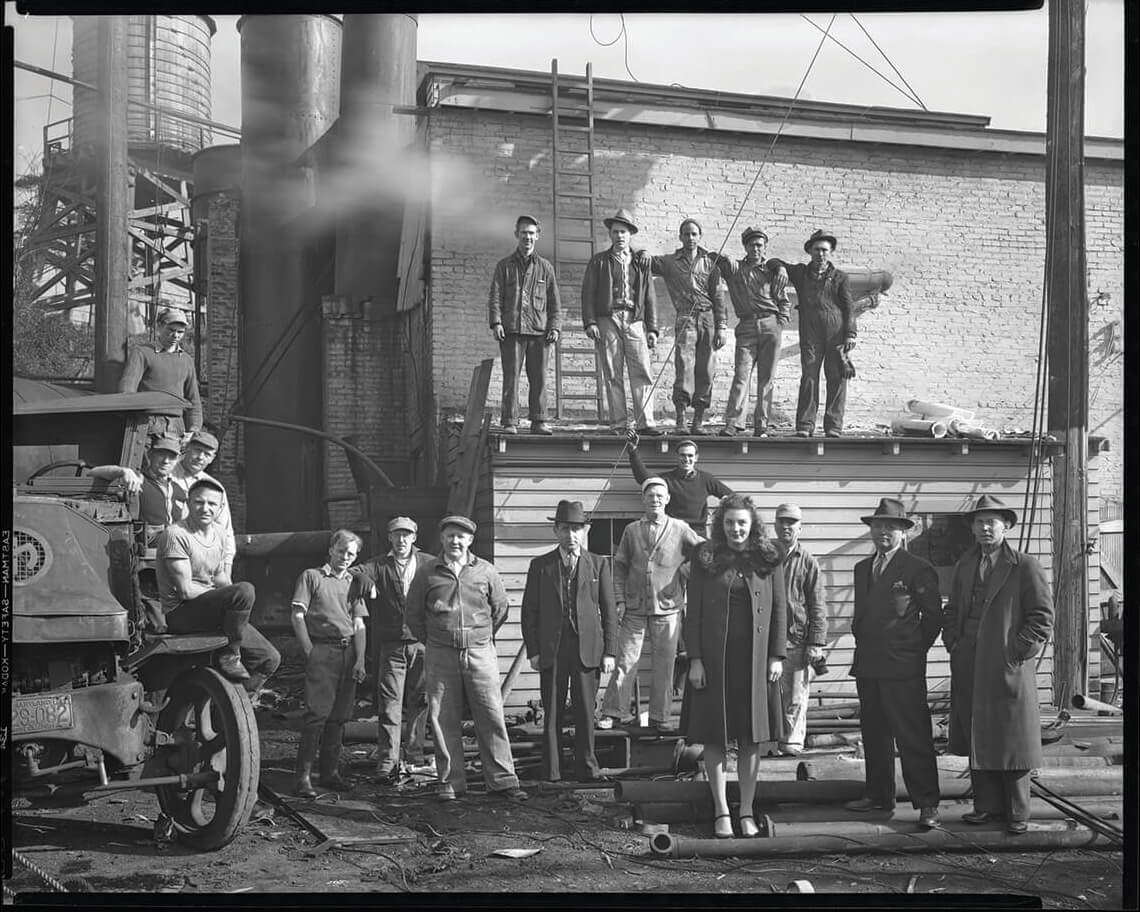

Workers and management at Monumental Distillery in 1942. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE, LARGE PRINT COLLECTION

Toward the end of World War II—another post-Prohibition blow—B.P.R. was gobbled up by the behemoth National Distillers Products Corporation, eventually being bought by Seagram’s, whose Canadian whiskey had become the new rage. By the time they closed the Dundalk doors in 1988—along with another sprawling location, known for producing Four Roses bourbon, which still sits abandoned on Willow Spring Road—the plant had been demoted to a storage facility, only manufacturing flavors for the likes of mere wine coolers. All 12 employees were let go and, after sitting empty for decades, the buildings were deemed a safety hazard and torn down to community applause in 2017.

But by the time of demolition, the county had already designated the old brick smokestack and its deteriorating water tower as landmarks for historic preservation, with both still standing to tell their story today:

That this town, this city, this state has an intoxicating past, dating back to a time not that long ago, before anyone had even heard of a little old place called Kentucky. And that we almost left it all on the barroom floor.

Though a growing community here in Baltimore—and beyond—has asked for one last call.

The Baltimore

Pure Rye smokestack.

hen considering the national spirit of the United States in this day and age, one clear winner quickly emerges. By all accounts, whiskey—and not just any whiskey, but bourbon whiskey, from the rolling hills of the aforementioned Kentucky—is to America what tequila is to Mexico and vodka is to Russia. It is the stuff of blues music, of John F. Kennedy, of Casablanca, of the streets of New Orleans—as patriotic as baseball or Budweiser, its less potent little cousin.

But long before the Bluegrass State came to define our liquor cabinets, bar wells, and bottle-shop shelves, it was another whiskey—rye whiskey, distilled from a base of rye grain, compared to bourbon’s corn—that dominated the nation’s drinking scene, and for nearly two centuries at that. Even George Washington made the stuff (and quite a lot of it). And for a long time, the Mid-Atlantic was the epicenter.

“Rye was the first American whiskey,” says James Beard Award-winning cocktail historian and drinks-world icon David Wondrich, who grew up near Pittsburgh, one of the spirit’s primary hubs. “The bourbon industry has been in charge by default, but the true roots go through Pennsylvania and Maryland. That’s the heartland.”

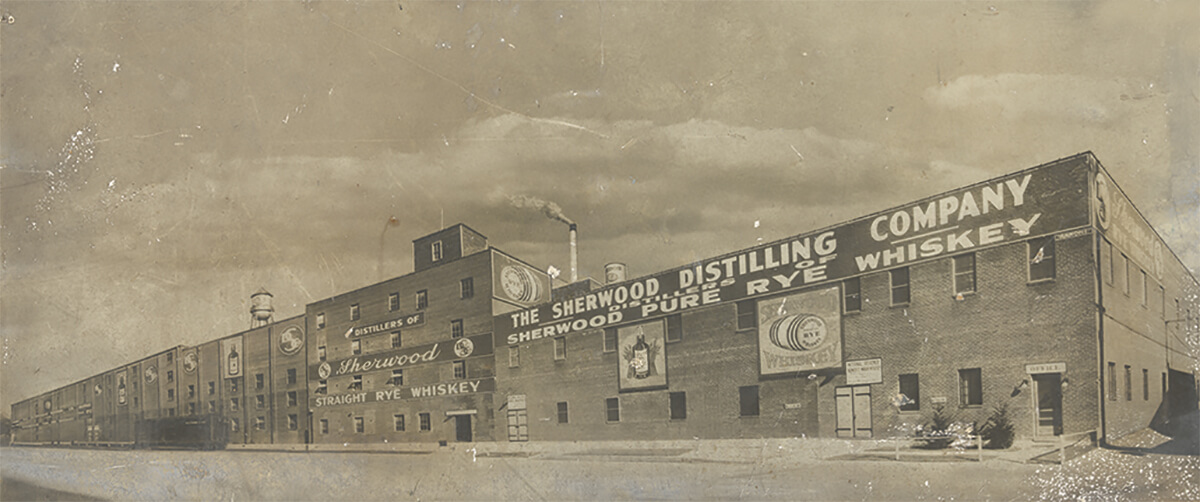

In the Old Line State alone, dozens of distilleries once produced millions of gallons of rye whiskey annually, with factories lining the streets of Baltimore and revered brands—Hunter, Mount Vernon, Monticello, Melrose, Sherwood—helping to raise the spirit from its rustic countryside origins to the finest white-tablecloth clubs, five-star hotels, and caviar-studded dining cars from New York to California, earning a reputation the world over along the way. In fact, at some point, our signature “Maryland rye” was so well-known, it became the only whiskey of its kind cited as a geographical style in the federal code of the U.S. Treasury.

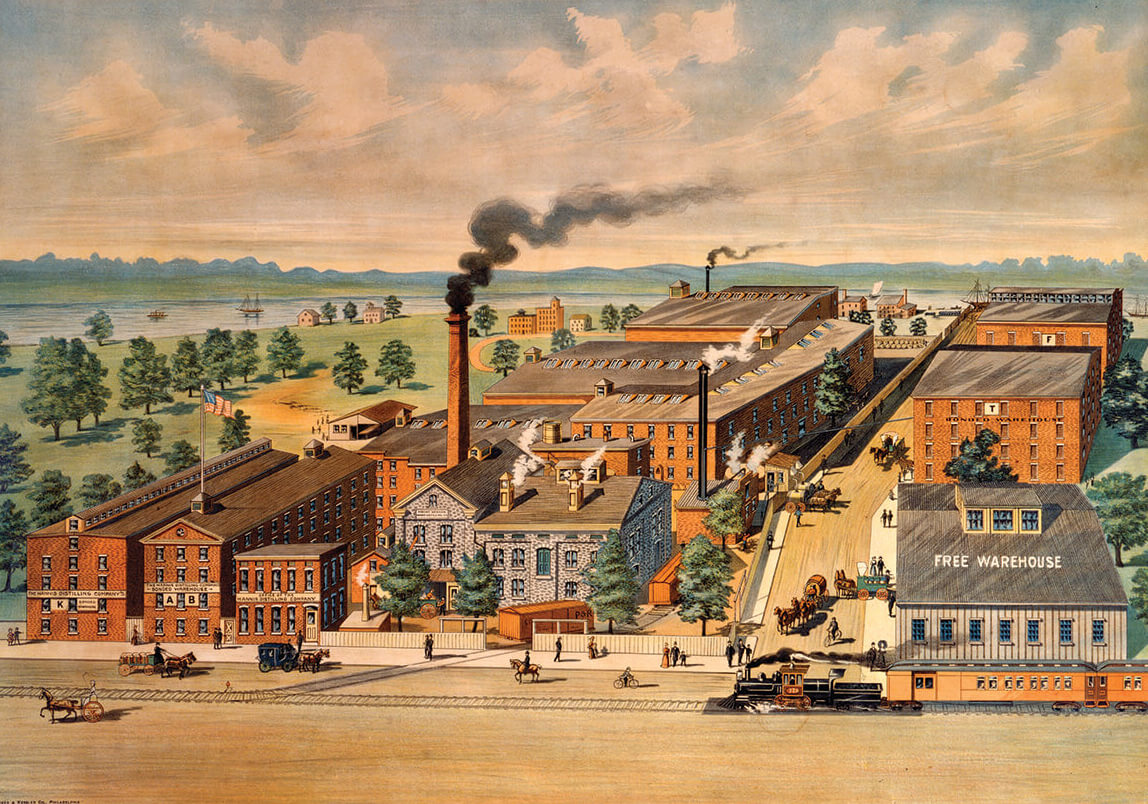

A view of the Mount Vernon Distillery in 1891, located just south of today’s M&T Bank Stadium. COURTESY OF THE MARYLAND CENTER FOR HISTORY AND CULTURE, LARGE PRINT COLLECTION

Not for the faint of heart, mind you, it was a spicy, strong, full-bodied drink compared to the soft, sweet sips of Kentucky bourbon—B.P.R. was even affectionately ordered as “Baltimore Paint Remover.” But think of white bread versus rye, for instance. Or better yet, envision it as The Sun once did, with “the ruggedness of the frontiersman and the self-reliant spirit that gave Maryland the name of the Free State.” After all, this was the spirit of proud, tough, Rust Belt cities like Baltimore (which got its “Wet City” nickname for defying Prohibition).

And luckily, it’s no longer ancient history. In the early 2000s, decades after brown liquor had fallen out of fashion in favor of gin, then vodka, then tequila and Bacardi rum, the craft cocktail emerged as the drink du jour. And as bartenders began to research the classics—Manhattans, Sazeracs, Old-Fashioneds—they revealed that rye whiskey was often enough their concoction’s base.

Suddenly, the spirit was cool again, and over the years that followed, a wave of distilleries would rise up to revive its storied birthright, including a handful right here in Maryland. Call it a comeback—one that might restore a great American legacy along the way.

“People want that tradition,” says Wondrich. “Showing them ‘this is what we drink here’ says ‘this is who we are.’”

Bottles are filled

with rye whiskey at the Sagamore Spirit Distillery.

n all honesty, at first, we were rum drinkers in this country. Though Native Americans might have lightly dabbled for ceremonial purposes, the creation and consumption of hard alcohol largely immigrated to the New World with European settlers. Soon enough, their homeland traditions became well-established, and the fruits of newfound farms and orchards were being fermented into ciders and beers, then distilled into brandies, in part to fortify their diets and fend off the impurities of drinking water.

All that changed with the British rum trade in the mid-1600s, when colonists are said to have each consumed nearly four gallons of the spirit annually. Whatever the true figure, it had its loyal following, so much so that stiff taxes on the alcohol and its ingredients of molasses and sugar would at least partially inspire the American Revolution. Afterward, its popularity significantly declined as whiskey moved in.

In those early days, Maryland was an agrarian society. To the south and east, tobacco was king, while in the northwest, Piedmont soil was better primed for growing grain. Wheat would help transform Baltimore from a sleepy backwater into a booming, mill-powered metropolis, with the ever-hardy rye being a common cover crop in between. As a matter of economics, a simple pot-style still became standard farm equipment, with any surplus harvest distilled into whiskey, and the spent rye then fed to livestock. With no real roads, rails, or canals yet, the spirit was easier to haul to market on horseback than its original grain, and brought a higher profit, too.

By the late 1700s, rye whiskey would yield a thriving industry just north and west of Baltimore City, with many dozen micro-distilleries likely existing throughout the region. That’s largely thanks to an earlier influx of immigration. In the first half of the century, Germans, as well as Scots-Irish, settled around the Mid-Atlantic, and like others before them, they brought their agricultural know-how and distilling traditions. Some among them were the Frederick-based ancestors of the one and only Jim Beam, whose great-grandfather, Jacob, would eventually make his way to Kentucky, like many other Marylanders and Pennsylvanians of the day—some monetarily incentivized to relocate to its undeveloped land by the “Corn Patch and Cabin Rights Act” of 1776; others doing so out of spite, having been incensed by further alcohol taxes enforced in the north. Ultimately, these southwestward migrations would light the spark for bourbon’s impending takeover.

Checking the barrels at Baltimore Spirit Company.

For a little while longer, though, rye whiskey remained the favorite—and on the verge of a major evolution. Throughout the 1800s, small farm distilleries found steadily increasing competition in the big cities, where entrepreneurs like William and Edwin Walters (of the art museum) and Johns Hopkins (of the university) were getting in on the booze game. Baltimore’s port, then railroads, and general crossroads of commerce were obvious boons, and before long, countless brands flooded the market. The Civil War only helped the cause, when thousands of soldiers became acquainted with the spirit on their way through the region.

While Kentucky slowly but surely grew in the west, two main “eastern” styles of rye whiskey emerged: Pennsylvania’s popular “Monongahela,” named for the state river and known for its high, if not entirely rye mashbill—aka recipe—and the slightly secondary “Maryland” version, which at times also included a small percentage of barley or corn, perhaps making it a tiny bit sweeter. While no one knows exactly what made the two distinct, or so in demand, both of their successes are undoubtedly tied to not only a fair climate and fertile terrain, but also a vast underground limestone formation stemming from the Appalachian Mountains, which yields naturally enhanced water—an essential ingredient for good distilling. On top of that, many local distilleries, like B.P.R., used three-chamber pot stills to make their spirit, giving the rye “a rich, more flavorful, herbal, cedary, almost vegetal style,” says Wondrich, “different than anything we’re used to today.”

As Baltimore’s population surpassed half-a-million toward the end of the 19th century, downtown was a hub of hooch activity. One saloon existed for every 250 people and dozens of wholesalers hawked spirits at local groceries, pharmacies, and department stores, with big hand-painted letters advertising their wares on building facades across the city skyline. Bottle and barrel makers rose to occasion, with more than half of the state’s 40-plus distilleries were scattered in and around the city, including at least two billowing smokestacks within sight of City Hall.

One was the Monticello Distilling Company on Holliday Street, beloved by the father of H.L. Mencken, whose rye the Sun columnist called “the most healthful appetizer yet discovered by man,” being that it was also prescribed as medicine by the family doctor. There was alsothe Walters family’s Orient on the Canton waterfront, too, and the four-acre Mount Vernon near M&T Bank Stadium, and Lanahan & Stewart on Light Street, whose blended Hunter brand would grace London theaters and the pages of Life magazine. Not to mention the county’s famed Sherwood and Sherbrook distilleries, whose head distiller Frank L. Wight was something of a household name.

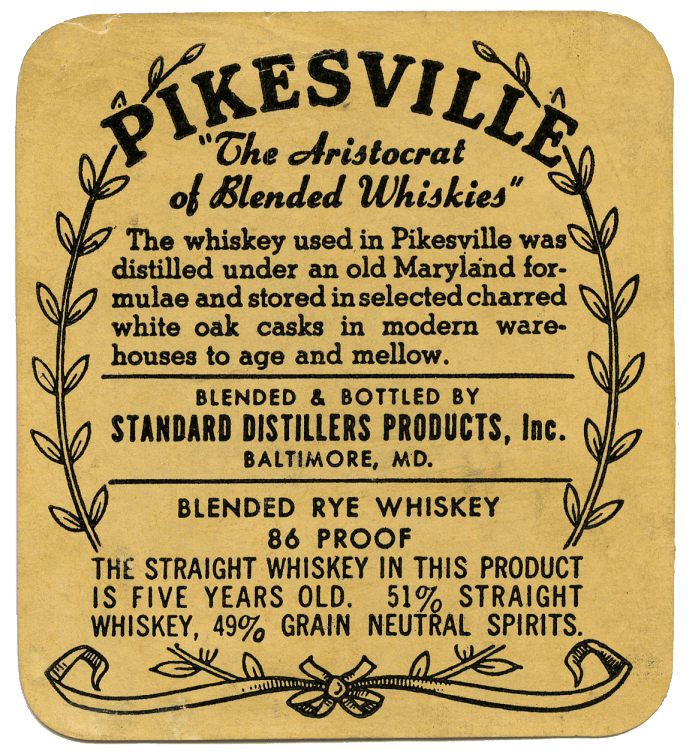

And out there, too, was Pikesville, born just outside of its namesake neighborhood in 1895, during the height of the rye whiskey industry.

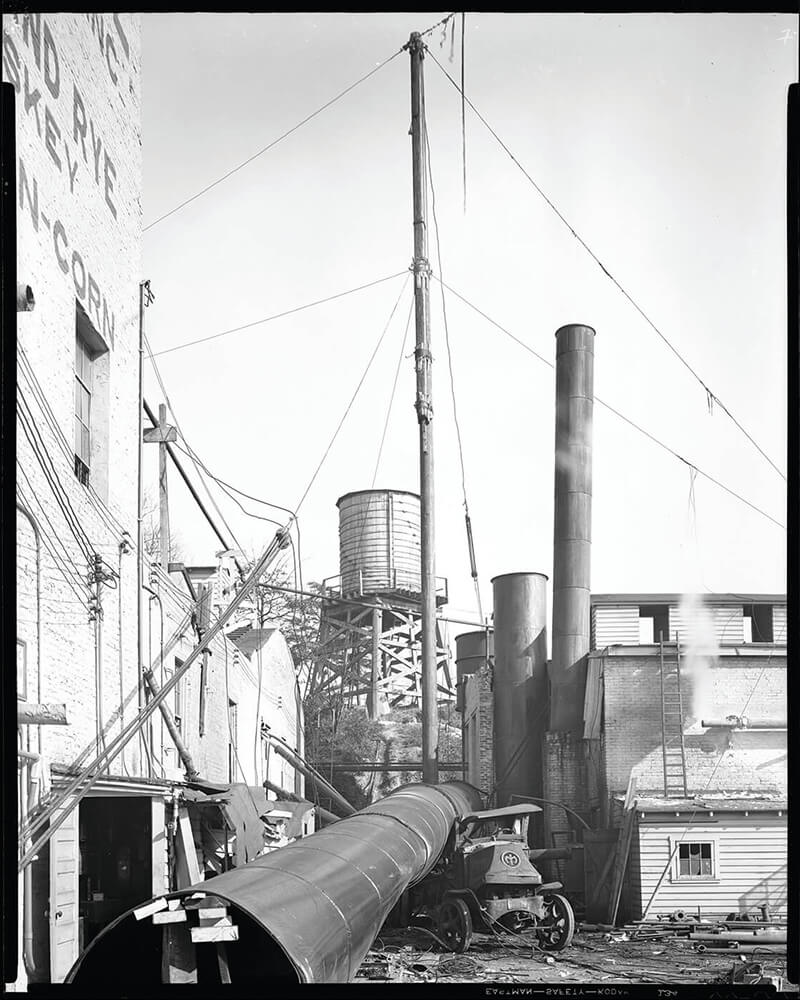

Above: The

old Pikesville distillery

in 1942. COURTESY OF HEAVEN HILL DISTILLERY; The pot

still at Baltimore Spirit

Company in Hampden; Throwback

bottles of Pikesville.COURTESY OF HEAVEN HILL DISTILLERY

alk into any Baltimore bar a decade ago, be it a neighborhood dive or a modern speakeasy, and chances are that you would find a bottle of white-labeled Pikesville Supreme. Order a shot, and you’d get Pikesville. Ask for a Manhattan, and fifty-fifty odds, it would be made with Pikesville, too. As much a fixture as cans of Natty Boh on the bartop, bags of Utz by the cash register, or Orioles on the TV, this inexpensive, surprisingly smooth, everyman’s whiskey was—and perhaps in some ways always will be—the city’s go-to rail drink.

Which was a bit of a paradox. On one hand, rye whiskey had clearly fallen from its 1800s heyday, relegated from top billing to the bottom shelf, with even Pikesville once deemed a fine pour. And on the other, despite a long slow death in the name of Smirnoff and Jose Cuervo everywhere else, here it still was. Somehow, even decades after the distilleries were gone, rye remained rooted, even subconsciously, in our sense of place.

“We took it for granted,” says Max Lents, who discovered those white-label bottles through Two-For-Tuesday drink specials at the Ottobar rock club in 2008. “So many people were drinking rye, when no one else in the country was drinking rye, that nobody thought about it, nobody talked about it, but it was there.”

Later, as a manager at the Joe Squared pizza bar, Lents couldn’t help but notice the craft-cocktail craze unfolding before him—all the fancy ice cubes, and fire-singed citrus, and mustached bartenders. He started to delve deeper, piecing together what little remained of rye whiskey’s local history. Also inspired by the rise of craft breweries, he and two friends, Ian Newtown and Eli Breitburg-Smith, all of whom were homebrewers, began moonshining in their kitchens, and before long, a wall of Sticky Notes and Sharpie turned into a business plan. What would become the Baltimore Spirits Company opened in Remington in 2015, releasing their first barrel of Epoch three years later—becoming the city’s first new rye whiskey distillery in decades.

Before that, Pikesville was the last to be made in Maryland. The distilling industry had been hammered by the first half of the 20th century. Two World Wars diverted alcohol production for the war effort and, in between, Prohibition outlawed it outright, from 1920 to 1933. Supplies ran low. Distilleries closed, sold, or transformed into other industries. And after Repeal Day, watered-down blends out of whatever was left found new favor, thanks to a generation now accustomed to the lighter Canadian whiskey that had been smuggled over the border during the ban—the beginning of a cultural shift toward lighter spirits, and the end for rye.

And all the while, Kentucky’s industry flourished, having already become the powerhouse of whiskey production by the mid-19th century, superseding even Pennsylvania, let alone Maryland, as populations and transportation expanded westward. Land was cheap, plentiful, and less desirable, allowing them to weather tough economic times. Corn grew copiously and, soon enough, the crop became federally subsidized to aid farmers through the Great Depression. To make matters worse, their corn-heavy “western” style of rye was sweeter and easier to drink, increasingly made using faster and more efficient column-style stills (though purists say this removes the nuance).

“After Prohibition, bourbon was in a better position,” says Wondrich, noting that several distilleries had been permitted to continue production for “medicinal purposes” during this time, most of them based in Kentucky. “These places kept going, and kept the knowledge alive.”

Meanwhile, into the mid-century, Maryland attempted a second act before ultimately drying up entirely. Pikesville’s local production ended in 1972, first moving to Pennsylvania, and then a decade later, the brand was bought by Kentucky’s Heaven Hill. Although it was now made outside of Louisville, in the heart of Bourbon Country, almost all of the spirit’s consumption continued to occur in Baltimore, pouring through the Mount Royal Tavern and the Maryland Club alike—even though the drink’s tweaked mashbill meant it was no longer “Maryland-style,” per se.

Then in 2016, just as rye whiskey was beginning to make a national comeback, that old white label was discontinued entirely, replaced by a small-batch, six-year-aged, 110-proof bottle of the same name that now sold for $50 a pop (compared to the bottom shelf’s 80 proof and 18 bucks). It’s “a smooth, balanced, sophisticated, small-batch rye whiskey . . . a real Goldilocks,” says Conor O’Driscoll, master distiller at Heaven Hill, whose company also purchased the former Pennsylvania brand, Rittenhouse. At the craft cocktail’s zenith, the public was demanding a more refined and robust product, giving their libations that extra punch.

And so a frenzy ensued. But not the kind one might expect from a town full of bona fide whiskey connoisseurs, known for gathering at monthly meetings, filling Facebook chats and Reddit threads, and staking out estate sales for “dusties,” aka sought-after vintage bottles, like those now carefully kept in the extensive James H. Bready Collection at the Maryland State Archives, named for the former Sun reporter who can be credited with most of what we know about the state’s rye whiskey.

Instead, drinkers of all ilks stormed their local bars and liquor stores in search of the very last of that good, cheap, old stuff, draining their stocks and snagging as many fifths as they could find, until there wasn’t a drop left. Although dozens of cases likely still live on, stashed away in the attics and basements of Baltimore City.

“I still have one and a half bottles left,” says Lents.

Above: Checking

the barrels; bottles marching through the

conveyor belt; sifting through the rye grain

at Sagamore Spirit in Port Covington.

ut now he doesn’t necessarily need it. In the back warehouse of the Union Collective in Hampden, some 600 white-oak barrels are stacked to the ceiling in the new Baltimore Spirits Company headquarters. Each is filled with about 50 gallons of what will become “straight” rye whiskey, simply meaning that the alcohol is aged for at least two years, to impart the wood’s natural color and flavor. It’s a legal designation enlisted after the Wild West of the late 1800s, when unscrupulous blenders and bootleggers used artificial additives to cut corners and create a product more akin to liqueur.

In fact, it was practices like these that muddied the waters of what made a Maryland rye “Maryland rye” at all, and spirit snobs have spent decades squabbling over the definition. Lents may make the real stuff, but he’s no purist; “Maryland rye” is really a matter of geography and quality, he insists, more than one specific formula or recipe. Besides, most of those were lost to history—either never saved in the first place, misplaced in the shuffle of a dying industry, or perhaps destroyed in the Great Baltimore Fire of 1904, when dozens of distilling company headquarters along Gay, Lombard, and Pratt streets went up in flames. One thing that can be agreed on: The vast majority of the mashbill will be rye grain, compared to the industry minimum of 51 percent, as is now the case in Kentucky’s Pikesville. B.P.R. in Dundalk used 98. Which is why the Baltimore Spirits Company only uses 100.

To make their spirit, they receive 2,000 pounds of grain from a Frederick County farmer. It gets milled on-site, then transferred to a 1,000-gallon tank known as a “mash tun,” where it is mixed with water and heat, allowing enzymes from a small portion of malted rye to break down the grain’s complex starch into simple sugars. After about an hour, the mixture, known as the mash, is cooled, then piped into one of two Douglas fir vats, where it will ferment with yeast for several days. As the yeast eats the sweet stuff, it begins to create alcohol, which, at this point, is essentially how beer is made.

But instead of stopping there, the mash is pumped into one of two old-school copper pot stills, where, like a hot pan deglazed with wine, the alcohol will be heated and vaporized, passing as steam into a condenser to be captured and cooled, ultimately turning back into a liquid, before repeating the distilling process a second time, taking about two days in total. In the end, this process will yield about two barrels—or, once water is added to dilute the spirit to its desired proof, 100 gallons of rye whiskey—equating to about 240 bottles each.

“When we released our first barrels in March 2018, we had lines out of the distillery, up the driveway, and onto the exit for I-83,” says Lents, who also released the brand’s four-year-old Reserve earlier this year. “We saved a few bottles for ourselves, to make sure that we could taste it—the first rye distilled in Baltimore in at least 50 years.”

Baltimore Spirits Company wasn’t the first to make this whiskey again in Maryland, though—that distinction goes to Lyon Rum on the Eastern Shore, back in 2014. Now, there are more than a dozen distilleries making some iteration of the spirit throughout the state. And while Lents and company took the cake in city limits, down along the edge of the Patapsco, in the shadow of the old Sun printing plant, on a quiet underpass beside the swinging cranes transforming Port Covington into the Baltimore Peninsula, Sagamore Spirit was right on their heels.

The two distilleries couldn’t be more different. For starters, Sagamore is big—really big. While the Hampden outfit leans toward “artisan,” this stately campus of stone and steel along the south waterfront harkens back to rye whiskey’s factory towns of yore, as well as the well-heeled countryside of Reisterstown, where Under Armour CEO Kevin Plank first devised the idea for this distillery after finding a natural limestone spring on his Sagamore Farm. That water is now being used to finish their own whiskeys, and grain grown on that same property, plus several other nearby farms, is added to their two mashbills—one “Maryland-style,” with 95-percent rye and malted barley, and one more a la Kentucky, made with 43-percent corn.

The goal? “To make rye famous again,” Plank told Baltimore in 2015, embracing an ambitious scale for his distillery—to serve as a neighborhood beacon, and to usher in the next notable chapter of the spirit’s long history in Maryland, which both now seem increasingly likely. This fall, Sagamore, whose products were already sold in 41 states and 15 countries, was acquired by Illva Saronno Corporation, the Italian liquor giant behind Disaronno, which will soon move its North American headquarters to Baltimore.

To help get the distillery off the ground in 2016, Sagamore’s first few runs were made with whiskey mass-produced from Indiana, but by 2021, their own house rye hit the market—an occasion that was followed by shots for the staff at Ryleigh’s Oyster in Federal Hill. Still blending the last of their Midwest inventory into a portion of the bottles, they aim to have an entirely local lineup by 2025.

Today, a 25-person team runs 10 shifts a week, each using about 10,000 pounds of grain, fermented across one of nine 6,500-gallon tanks and triple-distilled with a 40-foot-tall copper column still, named Penny, to produce about 15 barrels of rye whiskey, aka about 40,000 gallons annually—roughly 10 times that of Baltimore Spirits Company.

But even in an exceedingly competitive market, there’s still enough to go around. According to the Distilled Spirits Council, rye sales have grown from $15 million in 2009 to $356 million last year. And no longer a novelty, craft cocktails are now commonplace, with few signs of slowing down anytime soon.

“Everything comes to a saturation point, where it’s tougher to find shelf space, but as the consumer becomes more educated, they’re noticing quality,” says Ryan Norwood, COO at Sagamore. “Our hope is that high tides raise all ships.”

But before all that rye finds its way into your glass, it’s aged for at least four years in Sagamore’s two warehouses on North Point Boulevard near Dundalk, less than five miles as the crow flies from the old smokestack of B.P.R.

Above: Baltimore County's famed Sherwood Distillery, whose head distiller Frank L. Wight was something of a household name; vintage Pikesville labels. Courtesy of the Maryland State Archives

nd so it goes for our iconic booze—ebbing and flowing, with perhaps a good run now going into the future. In May, Governor Wes Moore declared rye to be Maryland’s official state spirit, which could pave the way for national recognition and cultural tourism like Kentucky’s “Bourbon Trail,” which would lead right into the heart of Baltimore.

And there, in Fells Point, on the corner of Bond and Fleet Street, you might find a seat at the turquoise bar at Southpaw, where three small frames hang on the memorabilia-strewn wall, each featuring a different vintage label of the city’s old standby, Pikesville.

A pour at Sagamore Spirit; a vintage bottle from Sherwood.

It was this same whiskey that, over a decade ago, owner Doug Atwell poured freely and helped remind the city of its celebrated past. In 2011, he co-opened Rye, a beloved watering hole just down the street on Broadway, and in fitting fashion, many a night, that white-labeled bottle, alongside Pennsylvania’s Rittenhouse, held a prominent placement throughout the menu, be it as a last-call shot, neat pour, or ingredient mixed into some of the city’s first old school-inspired cocktails. One riff on the Diamondback—once the house drink at the glitzy Lord Baltimore Hotel lounge—was made with, you guessed it, Pikesville.

As would only be right, during his new bar’s opening night last summer, Atwell was gifted a few of those long-gone, bottom-shelf bottles. But now, Baltimore Spirits Company’s Epoch sits at the ready on the bar—a torchbearer of a new era—nestled between Kentucky’s Buffalo Trace and Elijah Craig.

“Rye whiskey is woven into our identity,” says Atwell, a lifelong Marylander, who has one of those old park-bench planks, hailing Baltimore as the “Greatest City in America,” hanging above his bar. “All the folks who are making it today have such a reverence for what used to exist here,” he says. “And the fact that we can order it again feels like a secret history has come back to life.”