For the diehard baseball fan, the one who starts counting down the day after the World Series ends, Opening Day is more than just the start of another season. It’s a second New Year’s Day, when spring is eternal, every team is in first place, and all’s right with the world, if only for 24 hours.

Almost everyone has a special Opening Day memory, often centered around their first trip to what is always a big game. In my case, it’s the afternoon I attended the Orioles’ very first home game April 15, 1954—to this day the biggest baseball thrill of my life.

But it was 60 years ago, April 8, 1963, that I had my most unusual, and unforgettable, Opening Day experience.

As part of the Baltimore News American coverage team for the first time, along with sports editor John Steadman and lead baseball writer Neal Eskridge, it would be my first “road game” assignment, a milestone of sorts on its own.

In addition, it would be John F. Kennedy’s third Opening Day as president, only the second in the relatively new District of Columbia Stadium, which had replaced Griffith Stadium as home for the expansion Washington Senators after the 1961 season.

So, with an anxiety level already off the charts, imagine the feeling when a funny thing happened on the way to the press box and my trip took a detour to the Orioles’ dugout—where my assignment changed from sportswriter to batboy.

To WHAT?

No one, certainly not me, seemed to know why, but the visiting team did not have a batboy for the most important game of the year. It quickly became a topic of conversation during a pre-game chat with players around the Orioles’ dugout, a normal activity then but rare today. It certainly wasn’t the most important item on his agenda, but eventually the discussion got around to O’s manager Billy Hitchcock relaying that, for whatever reason, the Orioles didn’t have a batboy.

One version had it that the batboy was part of the union which also represented, among others, hot dog vendors, and had threatened a picket line to make things uncomfortable for the President. But that sounded like a lot of baloney. Another said the batboy had to be 21, but that hadn’t been a deterrent for the home team, so the best guess is the most logical explanation of all: somebody simply forgot.

Not a situation like thundershowers that could threaten the start of the contest, but when is the last time you saw a game when a team didn’t have a batboy? When was the last time you saw players picking up their own bats after making an out, or tidying up the on-deck circle? The situation needed to be rectified, and since I probably had more experience in that job than my original assignment for the day, and therefore I was on a short list of candidates, I did what any self-serving sportswriter would do—volunteered.

“I can do that, and have done it before,” I said, matter-of-factly. It was a reference to my three-plus teenage years as a “clubbie” during Orioles’ International League days, when I would occasionally substitute for Elmer Medley on the visitor’s side or the home team’s Eddie Weidner, Jr., the son of the Orioles’ trainer and the man who was still in charge of the clubhouse.

Even in that more subdued era, I probably didn’t expect anything to come of it, but I underestimated Steadman, who never met a unique story angle he didn’t want to pursue. He was on the case in a matter of minutes and got me clearance from Weidner, Sr.—“Doc,” as he was affectionately known in the O’s organization—and okayed it with manager Hitchcock, who had more important things on his mind.

And just like that, “Batboy For A Day” became my first Opening Day sports writing assignment.

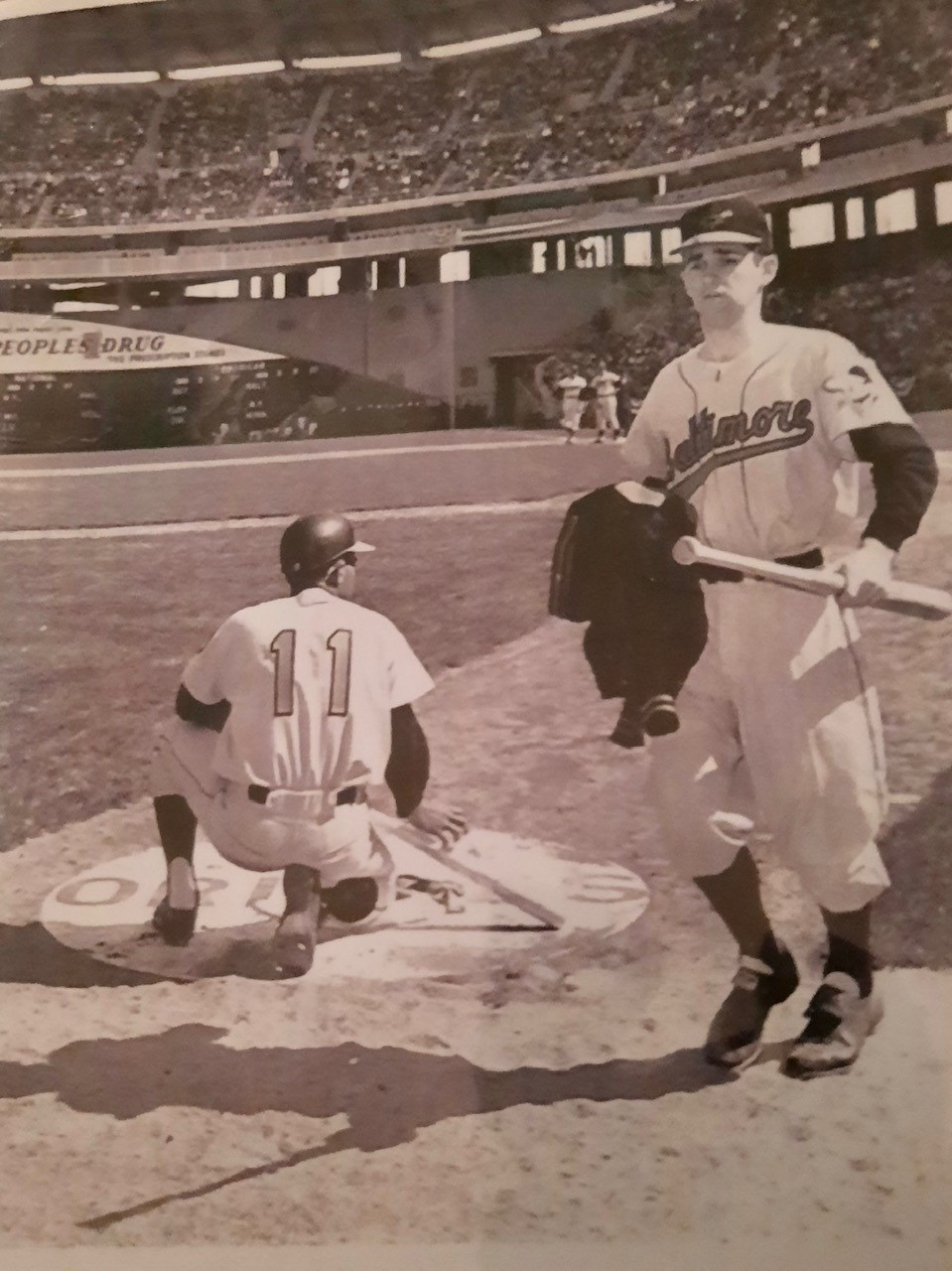

Before I could find a place to hide my typewriter (anyone remember them?) I was being fitted for a uniform. The Orioles’ rising, 25-year-old, soon-to-be-star third baseman contributed a sweatshirt and pair of size 10 spikes to complete the outfit. So, while it can be said that nobody will ever fill Brooks Robinson’s shoes, I did once walk in his spikes for a couple of hours. Not a bad memory.

Once dressed for my Major League debut, I got the standard pieces of advice from Weidner, the trainer—“Shake yourself young ‘feller.’” And the same message he’d given me more than a few times years before, “Stay out of the way and don’t leave any equipment laying around.”

That was a big thing with “Doc.” Nothing upset him more than having shin guards, gloves, weighted bats, resin bags, and/or donut rings scattered around the on-deck circle. Or a batboy angling for a photo op. No worries there.

“Hey you,” Orioles starting pitcher Steve Barber, a Maryland native whom I’d known long before either of us wore a big league uniform, shouted toward me before things got underway. “Anything you hear out there is off the record.”

“Great,” I thought. “The first quote of the day is about keeping stuff off the record.”

Some literary license, however, was allowed for comments about President Kennedy’s first pitch, which was caught by Senators’ catcher Ken Retzer. “He must’ve pitched last night, didn’t have much on that one,” O’s pitcher Robin Roberts, a future Hall of Famer quipped. “Even he throws a slider,” offered O’s coach/manager in waiting Hank Bauer. I also recall that there was a bit of a scrum as players scrambled to be the one to catch JFK’s ceremonial first pitch.

This was the fourth time Kennedy had thrown out a first pitch, and the second that I had witnessed—both from a distance. My remembrance is that JFK always seemed to have fun at the ballpark, which was especially true when he had duties for the 1962 All-Star game, also played in Washington.

I got to witness that one from the press box, but later was close enough to hear St. Louis Cardinal great Stan Musial utter the best quote I’ve ever heard in a clubhouse. “They said you were too young to be President, and I was too old to play ball,” Musial said while playfully poking JFK in the chest. “I guess we fooled them.”

Boog Powell told me recently that he didn’t actually recall seeing JFK’s ceremonial toss (he also didn’t remember who the batboy was that day), but he hasn’t forgotten shaking President Kennedy’s hand after the game all these years later. “He said something like ‘nice homer,’ which was kind of cool.”

In lieu of the tragic event seven months later, the comment that resonated the most was an overheard remark from a player that I couldn’t identify: “It’s amazing how close we were to him.”

Sixty years later, those words have become more poignant than they were in that moment.

A big thing for me that day was the fact that so many players, unlike Barber, were wearing an Orioles’ uniform for the first time. Included in that group were future Hall of Fame shortstop Luis Aparicio, whose bat would be the very first I would handle that day; right fielder Al Smith, one of the first Black players in the Major Leagues when he broke in with the Indians in 1949; and relief pitcher Stu Miller, a key component of the O’s 1966 World Series team three years later. They had no idea, and I’m sure cared less, that the batboy was a sportswriter in disguise.

Another lasting insight was hearing what ballplayers say in the dugout during the game. Turns out, it’s not much different than what you hear on the sandlots. They say “attaboy” a lot when good things happen…and unprintable stuff when things don’t go right.

But there was one term that I probably heard a half-dozen times before figuring it out. It happened whenever the Senators got a runner on first with less than two outs. “Let’s turn him over,” Hitchcock said without fail. To my uneducated ears that sounded suspiciously like instruction to disrupt the hitter with what they called a “dust off” pitch. It wasn’t until the eighth inning that I figured it out. That’s when Aparicio and second baseman Jerry Adair made a routine 6-4-3 double play. My “turn him over, was actually ‘turn ‘em over,’ short for “turn them over,” which, of course, meant to turn a double play—which even a novice like me should have known.

Another realization was that the game at the Major League level was a lot more difficult than perceived from the comfort of the press box. There was no better way to understand why Barber’s signature pitch, the sinker, was called “heavy”—it dropped hard into the catcher’s mitt—or why Stu Miller’s deceptive changeup was more than just another slow pitch. It’s still not like having a bat in your hand, but you definitely got a better feel from the on-deck circle. The game appears so fast from that vantage, you wonder how batters ever hit the ball—or fielders catch it. Put it this way: There’s a reason why ballplayers transition from dugout to press box and not the other way around.

There was a self-invoked “no fraternization” rule in place for me throughout the experience. Do not speak unless spoken to, find a place to hide in the dugout when the team is on the field, and, most importantly, don’t get in the way as noted. Even when Jim Gentile and Boog Powell both hit home runs in the second inning, there was no bat boy waiting to greet them at home plate. I stayed out of the photo opp.

The day proved eventful in several ways. Barber recorded his first win the year—the O’s won 3-1 behind those early home runs—on his way to becoming the first pitcher in club history to win 20 games. Miller got his first save as an Oriole and Aparicio was flawless in the field, including starting an eighth-inning double play to get Barber out of a jam. The still up-and-coming Birds would eventually finish 88-76—fourth-best in the then-10-team American League, won of course by the New York Yankees.

All in all. a pretty good day at “work.”

Many years later while serving as an official scorer for Major League Baseball for more than a quarter of a century, I was able to put my name on a lot of official box scores, which is pretty cool when I think about it.

As was wearing an official Orioles’ uniform once, even if it was just a funny thing happened on the way to the press box.

Jim Henneman is a past president of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America and is now in his eighth decade covering and writing about the Orioles. He began his career with the Baltimore News American before joining the Baltimore Sun and has been a longtime PressBox columnist and contributor.