News & Community

but there is a lull in the slim hours between its late last call and sunrise. In that quiet, at 5:34 a.m. on Dec. 4, 2024, surveillance cameras captured Luigi Mangione leaving the Hi New York City Hostel on an e-bike, according to the indictment brought by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office. The route from Central Park’s Upper West Side to the midtown Hilton where he allegedy headed would’ve been eerie in the predawn chill. Surreal, even, taking him past The Dakota, where John Lennon was killed 44 years earlier, and Strawberry Fields, the 2.5-acre memorial to the musician, peace activist, and most famous person ever murdered in New York.

By 5:52 a.m., prosecutors say, Mangione had arrived at the 46-floor hotel at 54th Street and the Avenue of the Americas, where UnitedHealthcare was holding its annual Investor Day conference. He paced outside the Hilton for 20 minutes before ducking into a Starbucks, where he bought a bottle of water and granola bars. Cameras there recorded what appears to be Mangione’s partially covered face and hooded head at 6:15 a.m.

Between 6:38 a.m. and 6:44 a.m., he stood against a wall on the north side of West 54th, adjacent from the Hilton. At 6:45 a.m., 50-year-old UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson strode toward the entrance to the Hilton where the conference was set to begin in a little more than an hour. Armed with a 9-millimeter, 3D-printed ghost gun and silencer, according to charging documents and now infamous CCTV footage, Mangione recrossed the street and followed Thompson for several yards, then shot him in the back and leg.

Two discharged shell casings had “DENY” and “DEPOSE” scrawled on them. “DELAY” was scratched onto a third unspent bullet recovered at the scene. They referenced what has been derided as the three “Ds” of the health insurance industry and the title of a 2010 book, Delay, Deny, Defend: Why Insurance Companies Don’t Pay Claims and What You Can Do About It.

Those words became a rallying cry for those who cheered the targeted killing of the head of the insurance division of United-Healthcare Group, a company whose revenues top Apple’s. Instead of sparking outrage at the brazen assassination and sympathy for Thompson’s teenaged sons and wife, the slaying unleashed a torrent of morbid glee, with comments like “thoughts and deductibles” posted on social media. Customers of UnitedHealthcare and other insurance companies expressed their anger and frustration in trying to get medical bills paid during some of the most difficult times of their lives and the lives of their loved ones.

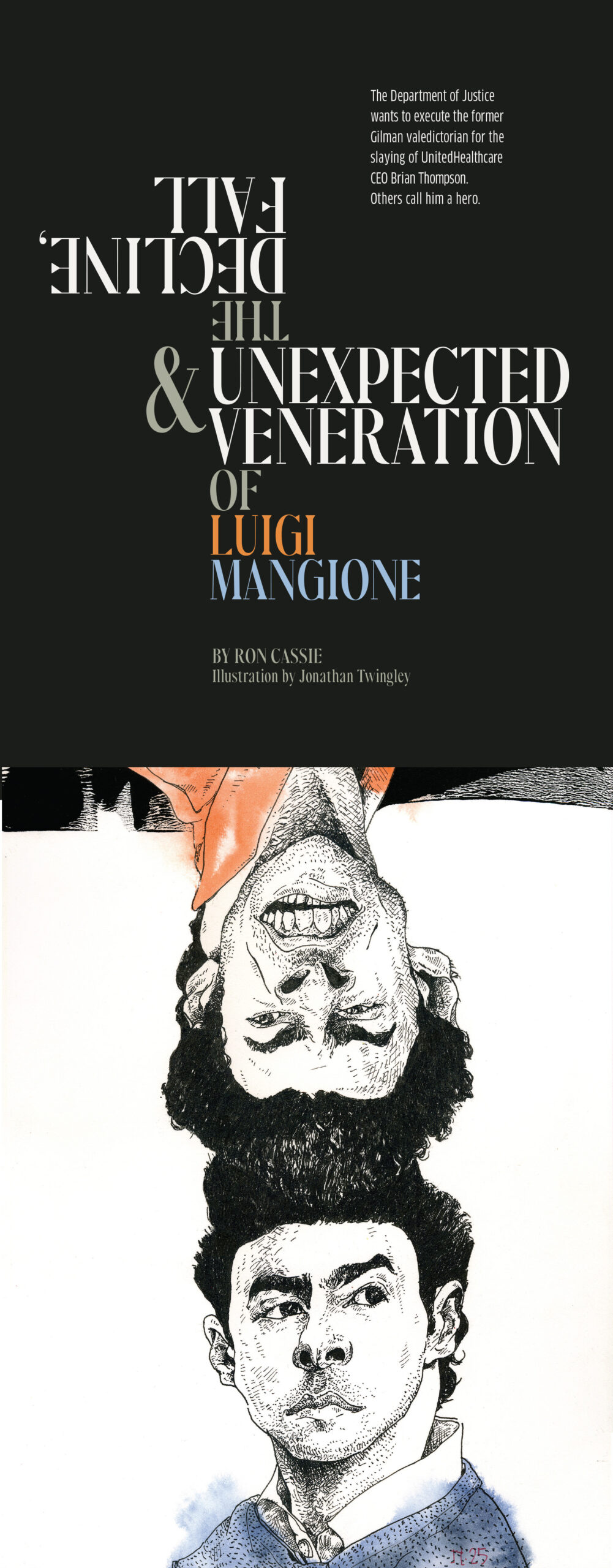

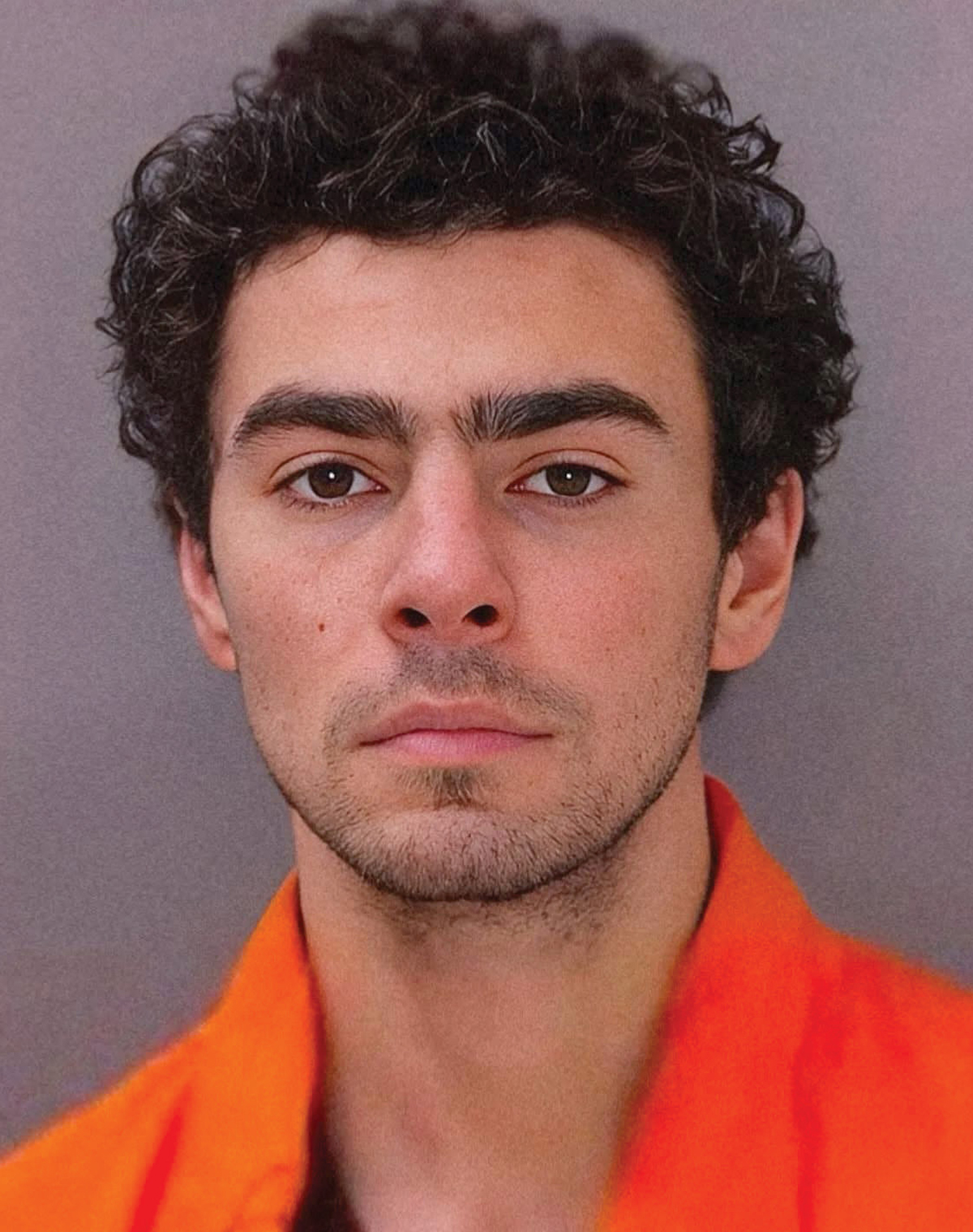

Even before Mangione was arrested in a Pennsylvania McDonald’s five days later, fans had nicknamed the mysterious assassin “the Adjuster,” hailing him a hero. After media identified him and released his mugshot, Mangione’s legion of defenders got tattoos of his CCTV visage, tweeted memes, and graffitied messages in solidarity with the former Gilman School valedictorian. Suddenly, there were images everywhere of “Saint Luigi,” a photoshopped portrait of Mangione in emerald robes with a golden halo circling his dark locks.

Within a week, a poster-sized version of “Saint Luigi” hung in Vito’s Pizza, just inside the Baltimore City line near Towson—an homage to Mangione, a frequent visitor as a teenager—and a Rorschach Test for customers. Some accused owner Guiseppe Mantova, whose 32-year-old daughter printed up the image, of supporting a criminal.

Others called in, claiming to be friends of Mangione’s and offering to pay for pizzas that Vito’s could hand out for free.

SAINT

LUIGI AT A SEATTLE LIGHT

INSTALLATION. —ALAMY IMAGES

year after Brian Thompson died on the sidewalk outside the Hilton shortly before the sun rose that December morning in Manhattan, the case against Mangione has only recently begun to move forward. The most significant news is that the two terrorism charges against Mangione brought by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office were dismissed as an overreach by Judge Gregory Carro at a September 16 hearing.

The other indictments brought by New York State, including a second-degree murder charge, were in the middle of their first substantial hearing the first week of December—with his defense arguing that he was not properly read his Miranda rights and that the backpack found when he was apprehended was illegally searched. (If the search of that backpack, which contained a gun and his “manifesto” is thrown out, it would be another significant defense win. However, the state of New York still has video and DNA evidence allegedly linking Mangione to the shooting.)

The other major indictments—the interstate stalking and related murder charge brought by the U.S. Department of Justice—have yet to get their first real hearing. That said, U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi, in line with President Trump’s wishes, announced that her office intended to pursue the death penalty even before the federal charges had been formally filed. That trial is expected to start later next year. The stakes could not be higher.

Meanwhile, Mangione’s enigmatic personal saga continues to play out in pop culture unlike anything in the modern media age. It’s not just the passionate support he’s received—thousands of letters of groupie fan mail in jail—or that we’ve seen more photos of his six-pack abs than stories about Thompson’s grieving family and the impact of the assassination on the insurance industry.

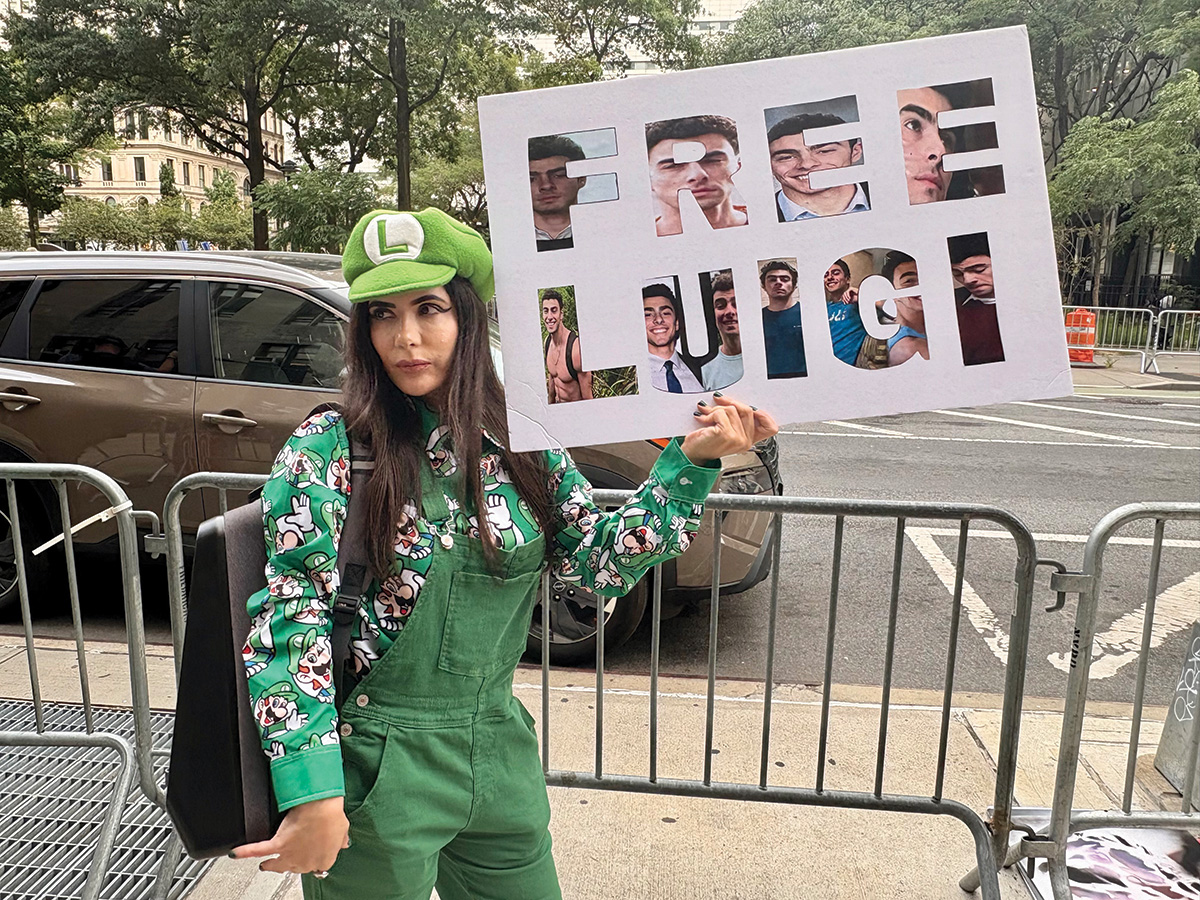

It’s the tragicomic response: SNL’s “Crime Stories with Nancy Grace” cold opening; Luigi: The Musical, centered around the fictional experiences of Mangione and fellow Metropolitan Detention Center inmates Sean “Diddy” Combs and crypto fraudster Sam Bankman-Fried, whose run at the San Francisco Fringe Festival sold out; fast-fashion giant Shein employing his AI-generated likeness to model shirts; the ubiquitous Luigi Halloween costumes; an online defense fund that’s received nearly $1.4 million in donations; and his legal team’s website, which explains how to send photos to Mangione. Not to mention, the appropriation of the kind-hearted, green-hatted “Luigi” character from the video game Super Mario Brothers, who has become an unexpected protest symbol for health-care reform.

And still, profound questions linger. Is the Ivy League-educated data engineer’s fall from grace best understood as a mental breakdown—or something else? A spiral of isolation, the internet, and ideology? Or was it what Mangione said he intended in his journals—the first blow in an anti-corporate, anti-health-insurance-for-profit revolution? (More on his vexing “Gray Tribe” politics later.)

The other side of this coin is the revelation that a swath of Americans, in particular, 41 percent of Mangione’s 18-29-year-old, Gen Z cohort, believe the health-insurance system is so corrupt, so overwhelmingly exploited by wealthy interests, that the murder of a CEO can be rationalized. That Thompson, who received $10 million in annual compensation for driving down claims and driving up profits, deserved what he got. Or, as it was put in a note police say they found on Mangione’s person: “Frankly, these parasites had it coming.”

“I can see how some people would link Luigi together with the man who shot Charlie Kirk [six days before Mangione’s mid-September hearing], both were young men. But to me, the two are not comparable,” says Breigh Marquisette, a 45-year-old paralegal who drove from Philadelphia to Lower Manhattan for the hearing with a life-size cutout of Mangione she’d purchased on eBay.

“One is a purely political assault,” she continued amid a chaotic scene outside the courthouse after the terrorism charges had been dropped. “The other is about placing profits over people’s lives. Luigi Mangione is innocent until proven guilty, but at the same time, to his credit, what we do know is that he was fed up with corporate greed.”

LUIGI MANGIONE ARRIVES IN NEW YORK BY HELICOPTER ON DEC. 19, 2024 TO FACE MURDER CHARGES AFTER HE DROPPED HIS OPPOSITION TO EXTRADICTION FROM PENNSYLVANIA.—GETTY IMAGES/MICHAEL NAGLE/BLOOMBERG

t’s not often the targeted killing of a CEO gets caught on grainy security video and then is followed by a drip-drip-drip of surveillance photos of the alleged suspect while the ensuing manhunt is underway. That said, the disturbing episode was beginning to fade from the news cycle until Mangione’s choreographed perp walk from a Pier Six heliport to a New York police van backfired. That spectacle, two-dozen heavily armed police, Mayor Eric Adams, and Police Commissioner Jessica Tisch marching the orange-jump-suited Mangione, went viral. Across social platforms, photographs of the handsome suspect were juxtaposed against the strikingly similar perp march of Superman in the 2013 movie Man of Steel, which of course only cemented his cult status.

Mangione has pleaded not guilty to all charges—and for a variety of reasons, not the least of which is his matinee idol looks—he has become the most dissected defendant to emerge from a series of headline-grabbing shootings. In a culture obsessed with true crime podcasts, his descent from private school kid to alleged vigilante assassin is the stuff of fascination.

Two documentaries have already been made about Mangione, who turned 27 while incarcerated this summer, with a Simon & Schuster book and feature docs by award-winning directors Alex Gibney and Stephen Robert Morse in the queue. A month ago, four New York Times reporters shared a byline on a front-page story that read like a travel piece, “exploring” Mangione’s time in Japan months prior to his arrest. Days later, People magazine ran an “exclusive” about their former cover boy, headlined, “Why Inmates Are Calling Luigi Mangione the ‘Ambassador’ at His Brooklyn Jail.”

However, in Baltimore’s close-knit Italian-American community, the response to the arrest was not fascination but disbelief—and concern for him and his family. That has not changed.

“My reaction, when I learned he had been arrested, was shock. My first thought was I felt for his parents. I mean, my God, it had to be the heaviest night of their lives,” says Giovanna Blatterman, following a busy lunch at Cafe Gia Ristorante in Little Italy, which is owned by her daughter and son-in-law. “It would be a knife through the heart of any mother. I can’t imagine the pain that they are going through. It’s like a living death. It’s terrible. It’s your beautiful child.”

Blatterman runs two Stiles Street bocce leagues and is acquainted with the Mangione clan, who have participated in the Italian pastime over the years. She adds family members visit the neighborhood for events at St. Leo’s and fundraising dinners and the like and always supported the local Italian-American community.

The family patriarch, Luigi’s grandfather Nick Mangione Sr., grew up in Little Italy. He was the son of an illiterate Italian immigrant, raised on a since-demolished block of Low Street. A hard-charging, complex, often combative businessman, he rose from bricklayer to influential developer and liked to compete whether it was at the negotiating table, at gin rummy, or on his golf course.

After serving in World War II, Mangione Sr. made his fortune in contracting, commercial real estate, nursing homes, golf resorts, and conservative talk radio—the family-owned WCBM. Six of his children attended Loyola University, the private Jesuit school on North Charles Street. All 10 of them, including Luigi’s father, Louis, eventually went to work in the family’s sprawling enterprise. Mangione Sr. shared his grandson’s Italian good looks, noted one female former reporter. He also possessed a temper and occasional vengeful streak when he believed his businesses or children had been treated unfairly. When Nick Jr., Luigi’s uncle and a former All-America midfielder at Loyola, was cut by the Baltimore Blast after four seasons, Mangione Sr. returned his 36 season tickets and vowed then-team manager Kenny Cooper would never be invited back to the family’s Turf Valley golf resort.

At the same time, Luigi’s grandfather’s quintessential American Dream funded, and continues to fund, major philanthropic efforts, with millions donated to area hospitals and the Archdiocese of Baltimore, among other causes. Loyola’s swimming complex bears the family name: the Mangione Aquatic Center. Luigi’s paternal grandmother, Mary Mangione, who passed away two years ago at 92, served on the boards of The Walters Art Museum and the Baltimore Opera Company.

But in fact, Luigi Mangione is not the product of one prominent Italian American family, but two. His mother Kathleen’s family, the Zanninos, have operated a successful funeral parlor business in the historically Italian section of Highlandtown for decades. Luigi’s 38-year-old cousin, Nino Mangione, a Republican state delegate, released a statement that the family was “shocked” and “devastated” by the arrest. They have not commented publicly since.

“These are families everyone in the Baltimore Italian-American community knows,” says Joe DiPasquale, the third-generation owner of his family’s namesake restaurant and Italian market. “I knew both sets of Luigi’s grandparents. We were neighbors and business associates, and unfortunately, customers, too [of the Zannino funeral parlor],” he says.

“When the news and first photos hit, someone sent me a text message, and I thought it was a joke. Then, there was a barrage of messages, and I still thought it was a joke. Because, you know, the initial images looked like him, but, obviously, it can’t be him. We were all so proud when he was named valedictorian at Gilman. What an achievement. I was in total disbelief like everyone else. Where is this coming from? Where did it come from?”

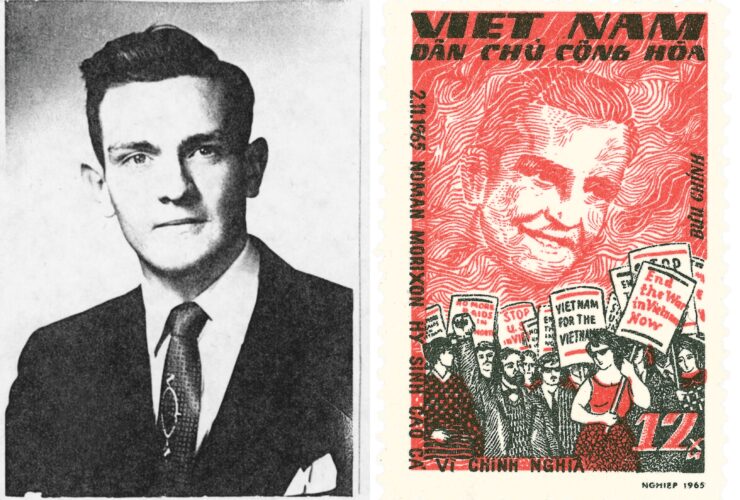

MANGIONE’S GILMAN SCHOOL

PORTRAIT; MUG SHOT.—ALAMY IMAGES

he rowhouse enclaves of Little Italy and Highlandtown, and the northeastern Baltimore area around St. Anthony of Padua, where his aunts and uncles attended grammar school, was not Luigi Mangione’s world. He grew up with two older sisters in a four-bedroom, five-bathroom home in a suburban Baltimore County cul-de-sac. (His sister MariaSanta, a physician at the University of Texas Southwestern, posted, “Praying for you,” after the arrest. His other sister, Luciana, shared a photo of herself and her brother smiling at the beach.) By middle school, his universe was built around Gilman, the elite, all-boys, K-12 prep school, where everyone knows everyone.

Classmates have characterized Mangione as likeable, athletic, and bright, with an interest in gaming, tech, and coding. No one perceived a hint of anything dark or dangerous about him while he was a student and certainly no one imagined him capable of anything resembling the crime of which he has been accused.

“He was someone who got along with everyone,” former schoolmate Hari Menon told ABC News after his arrest. “He was always funny, carefree, and smart as well. When we were in robotics [club], there was nothing that he couldn’t help out with. He was a person who I looked up to quite a bit.”

Freddie Leatherbury, from Mangione’s graduating class, described him as “one of the nicest kids” he knew at the school.

Retired Gilman teacher Chris Legg recalls Mangione from his valedictorian speech. “My reaction was sorrow for his family and just thinking that it was somewhat symptomatic of how challenging it is to grow up in this country,” Legg says. “A small percentage of people are going to go off the rails, but I can’t think of anything less characteristic of a Gilman kid, who obviously had plenty of talent. To a certain extent, it’s a search for identity, for purpose, that has gone horribly wrong.”

That Mangione rose to the top of his class is no small feat. Tuition for the Upper School is $40,000 and the alumni include former congressmen, governors, ambassadors, and U.S. senators. One graduate and former instructor described the culture as “insular” and “intense.” “A hothouse.” However, they said, it’s also a place from which its best students derive a sense of self-worth and identity.

“The kids are mostly amazing, but it’s largely people with money, whose lives revolve around the school, country clubs, and school sports, and the parents are mostly concerned with getting their kid into a college that they can brag about at cocktail parties,” the alumnus said. That may be harsh, but Mangione, who participated in several sports and clubs, thrived, as do many young men in the structure of the 128-year-old institution.

At the University of Pennsylvania, Mangione continued to excel. He graduated cum laude in 2020 with dual bachelor’s and master’s degrees in computer science.

That fall, Mangione began remote work as a data engineer at TrueCar, a website that enables users to compare prices of dealer-owned vehicles. He lasted a little more than two years, sharing with a Gilman classmate that “Data engineering paid super well but was mind-numbingly boring.” He said he wanted to “spend more time reading and doing yoga.”

That an Ivy League honor society member would find 27 months of remote data work underwhelming, lacking in meaning as well as connection—no office buddies, no happy hours, no dating opportunities—is not surprising. He never took another job, and no long-term romantic relationship has ever been reported. (One anonymous classmate remembered him as “very shy” with girls.)

Untethered to school, family, or job, he continued to drift. Gurwinder Bhogal, a British- Indian writer and cultural commentor with a computer-science background, was one of the last people known to have had a lengthy conversation with Mangione, who subscribed to his Substack. “I did get the sense he felt alienated,” Bhogal later wrote of their May 2024 video call. “He often decried the lack of social connection in the modern world.”

This is not a new phenomenon. However, the identity challenges facing those in their 20s and early 30s—20th-century psychologist Erik Erikson called it the “intimacy vs. isolation” stage of development—is increasingly fraught. The rise of remote work and the collapse of “third spaces” in the smartphone age has only exacerbated the isolation. The number of young adults eating all their meals alone has grown by 80 percent over the past two decades; 28 percent of men under 30 report having no close social connections—more than a double-digit increase since 2013.

As many know by now, Mangione exacerbated a chronic back problem in a 2022 surfing accident in Hawaii, where he had lived in a group housing co-op. (He had also complained of brain fog, possibly linked to Lyme disease.) After a debilitating and ineffectual period of therapy, he left Hawaii and underwent spine surgery in July 2023. Initially, some observers saw the X-ray image of four screws inserted into his spine, which he had posted to X, and assumed he was a UnitedHealthcare client who continued to suffer chronic pain, and believed it was behind his motivation for the murder. Not the case. In his own words, he had benefited tremendously from surgery—getting off pain meds within a week and praising the procedure repeatedly on social media.

Months later, Mangione departed on a backpacking trip to Asia, physically healthier but nonetheless increasingly distant from friends and family. He cut ties with acquaintances from Hawaii, as well.

“Luigi was a thoughtful and considerate friend and good to everyone,” says R.J. Martin, who founded the co-living space where Mangione resided while on O‘ahu. “He always volunterered to help out and left everyone and everything better than he found them.” But, as Martin has recounted, he also texted Mangione several times after his surgery and never heard from him.

Other clues to his state of mind have since appeared, indicating it had begun to deteriorate. Mangione was still active online in January 2024, when he posted a four-star, Goodreads review of “Unabomber” Ted Kaczynski’s 35,000-word manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. After returning from the trip to Asia in June, Mangione fell off the map.

Shortly before Thanksgiving in 2024, when his family normally would’ve been expecting him to make holiday plans, his mother filed a missing persons report in San Francisco. One friend said the family had also reached out to former Gilman classmates to find Mangione. Law enforcement officials said a photo from that report helped identify him during their search. When New York police contacted his mother during the manhunt, she told them she was not certain the individual in their surveillance images was her son, but “it was something she could see him doing.”

UNITEDHEALTHCARE CEO BRIAN

THOMPSON. —COURTESY OF UNITEDHEALTHCARE

he young man accused of killing UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson followed a mix of political, tech, and cultural influencers that defies easy categorization. On X (@PepMangione), they included Joe Rogan; Edward Snowden; Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez; New York Times columnist Ezra Klein; psychologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness; OpenAI CEO Sam Altman; Tesla; and vaccine denier RFK Jr.

Some accounts he followed focused on self-improvement, neurobiology, and psychedelic mushrooms. Others philosophized on the role of technology in society, preaching entrepreneurship and libertarianism. Mangione tweeted about agronomics, masculinity, Japanese birth rates—the solution “isn’t immigration,” but “culture”—and reposted messages about how to think logically.

He listened to manosphere commentator Jordan Peterson, debates on AI, and discussions of decision theory amid a constellation of tech-bro-adjacent subjects. He was anti-smartphone, however, and skeptical of traditional parameters of success. His posts were generally optimistic, secular, and scientific, seeking explanations and solutions. He shared atheist Richard Dawkins’ praise for religion on cultural principles—i.e. Christianity may be a fiction, but its decline has given way to something worse, leading to the worship of “intolerant new gods.”

In other words, like his alleged slaying, his digital footprint provides grist for everyone. Conservatives see a far-left, anti-capitalist thug; progressives, a spoiled “anti-woke” kid aligned with right-wing futurists. Supporters dot the spectrum from one end to the next.

So how do the pieces fit together? Most people would probably not be familiar with Mangione’s worldview. It is not common among politically animated killers. Those he engaged with online and his social-media history place him in a certain internet circle.

“Increasingly looks like we’ve got our first ‘gray tribe’ shooter, and boy howdy is the media not ready for that,” posted journalist, author, and extremism expert Robert Evans, after analyzing Mangione’s social media engagement on his Substack, Shatter Zone.

MANGIONE SUPPORTER BREIGH MARQUISETTE OUTSIDE HIS SEPTEMBER HEARING IN NEW YORK.—Ron Cassie

There is no official name for this hyper online, predominantly male subculture of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, coders, bloggers, and anonymous posters, who view themselves as beyond the mainstream definitions of “red” or “blue.” But “The Gray Tribe,” coined by psychiatrist and blogger Scott Alexander Siskind in 2014, is one term. Another is the Rationalist movement, sometimes described as Silicon Valley’s techno religion, and whose adherents share with Mangione an advanced academic background, a tech industry resumé, and an obsession with the societal issues AI has brought to the foreground. It preaches the use of logic, probability, and the avoidance of cognitive biases in decision-making—no matter how off-the-wall the result—as well as so-called effective altruism and mitigating the existential risk from artificial intelligence. The Rationalist community attracted early backing from Elon Musk and Peter Thiel.

But this movement doesn’t advocate violence. Millions follow the same individuals as Mangione and never resort to identifying a target, 3-D printing a gun, and pulling the trigger.

In the 262-word handwritten note found in his backpack when he was arrested in Altoona, Pennsylvania, Mangione took ownership of his actions:

“To the Feds, I’ll keep this short, because I do respect what you do for our country. To save you a lengthy investigation, I state plainly that I wasn’t working with anyone . . . many have illuminated the corruption and greed . . . and the problems simply remain. Evidently I am the first to face it with such brutal honesty.”

A DEMONSTRATOR OUTSIDE MANGIONE'S MID-SEPTEMBER HEARING IN LOWER MANHATTAN.—RON CASSIE

r. Naftali Berrill, a New York-based forensic psychologist who interned at Sheppard Pratt Hospital in Towson, says there are two hypotheses to explain Mangione’s seemingly inexplicable actions—distinguishing his motive from his psychological state. One, he suffered from an undiagnosed mental illness like schizophrenia, which can develop in the late teens or 20s, or a paranoid personality disorder.

Those are unlikely, however. If one or the other were the case, his defense counsel would have involved a forensic psychologist or psychiatrist by now, Berrill says. Without current evidence of either condition, and since it has been a year since his arrest, he believes Mangione falls into a second category, which is that “he’s terribly personality disordered and has a combination of highly narcissistic and antisocial qualities.” He adds the qualification that he has never met with Mangione. “He felt, or in his case, it might be more accurate to say, reasoned, his way into thinking that it was his job to execute this victim, and make a large social, political statement.

“Those with narcissistic and grandiose personality disorders become so full of themselves and entitled,” Berrill continues. “They feel that they can commit a terrible crime. They believe they’re special, unique, and can outfox law enforcement.”

Mangione, as his manifesto puts forth, was extremely angered by individuals like Thompson, who made millions while many customers couldn’t afford their premiums or medical bills. He also despised corporate greed more broadly. The exact details of any mental health issues, and how they might have interfused with his deep-seated anger, may never become completely clear.

Notwithstanding, criminal lawyers, like former WCBM talk-show host Tom Maronick, who had a longtime professional relationship with the family, still believe an “NCR” defense, meaning not criminally responsible based on insanity at the time of the shooting, remains most likely. Before she took his case, Mangione attorney Karen Friedman Agnifilo suggested it herself.

It may be perverse, but at this moment, Mangione could feel he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. The shooting brought renewed attention to the practices and profits of the health-insurance industry (if no real policy discussion among elected officials). And he’s held up by millions as a dashing Robin Hood-type figure (albeit, an allegedly violent one). Still, even if he avoids the death penalty, legal experts say he’s likely to spend the rest of his life, long after he’s gone gray or bald or gotten paunchy, in prison.

“Is he then a folk hero? Or is he then a victim of his own hubris? That becomes the question,” Berrill asks rhetorically. “He’s now locked away in MDC in Brooklyn and the chances of him ever seeing the light of day are slim to none. Someday, he’s going to ask himself, what exactly did he win?”