History & Politics

Pastor Believes Transformation of P.S. 103 Can Revitalize Old West Baltimore

Rev. Dr. Alvin C. Hathaway Sr. takes us on a tour of the 1877-built property that will soon become the Justice Thurgood Marshall Center.

Politics, not the office kind, cost Alvin Hathaway his first two jobs. The first, a computer programming gig for the B&O Railroad, was done in by the 1970 Clean Air Act (think fewer coal trains). The second, as a community court liaison for Milton Allen, the city’s first Black state’s attorney, got cut after William Swisher, a white candidate running a racially charged campaign, defeated Allen in his re-election bid.

“I was in my mid-20s, feeling sorry for myself, angry, too,” Hathaway recalls. “I still had a bit of an edge then.” A mentor suggested the now 69-year-old get out of Baltimore and see more of the world.

“He told me I needed perspective, and so I bought a $39 Greyhound bus ticket,” Hathaway says with a laugh. “I took the north route to San Francisco, where I had an aunt. I saw Notre Dame, Indiana; Minneapolis; Cheyenne, Wyoming. Then I took the southern route back out of Bakersfield. Saw the tumbleweed in New Mexico and passed right through Bristol—where its Bristol, Tennessee, on one side of the highway and Bristol, Virginia, on the other. I’d crossed the Mississippi at its narrowest point and its widest. I felt like Tom Sawyer.”

Late in his eight-month journey, a bus buddy tried to convince him to look for logging jobs in Portland, but Hathaway decided to come home.

“I had an uncle who was a pastor and activist in Richmond, and he told me he had work for me,” Hathaway says. “He brought me back into community advocacy and social-justice organizing, then I returned to Baltimore.”

In 1977, he became one of the organizers behind BUILD, the still-thriving Baltimoreans United in Leadership Development, a non-partisan, interfaith, multiracial community organization grounded in the city’s neighborhoods and congregations.

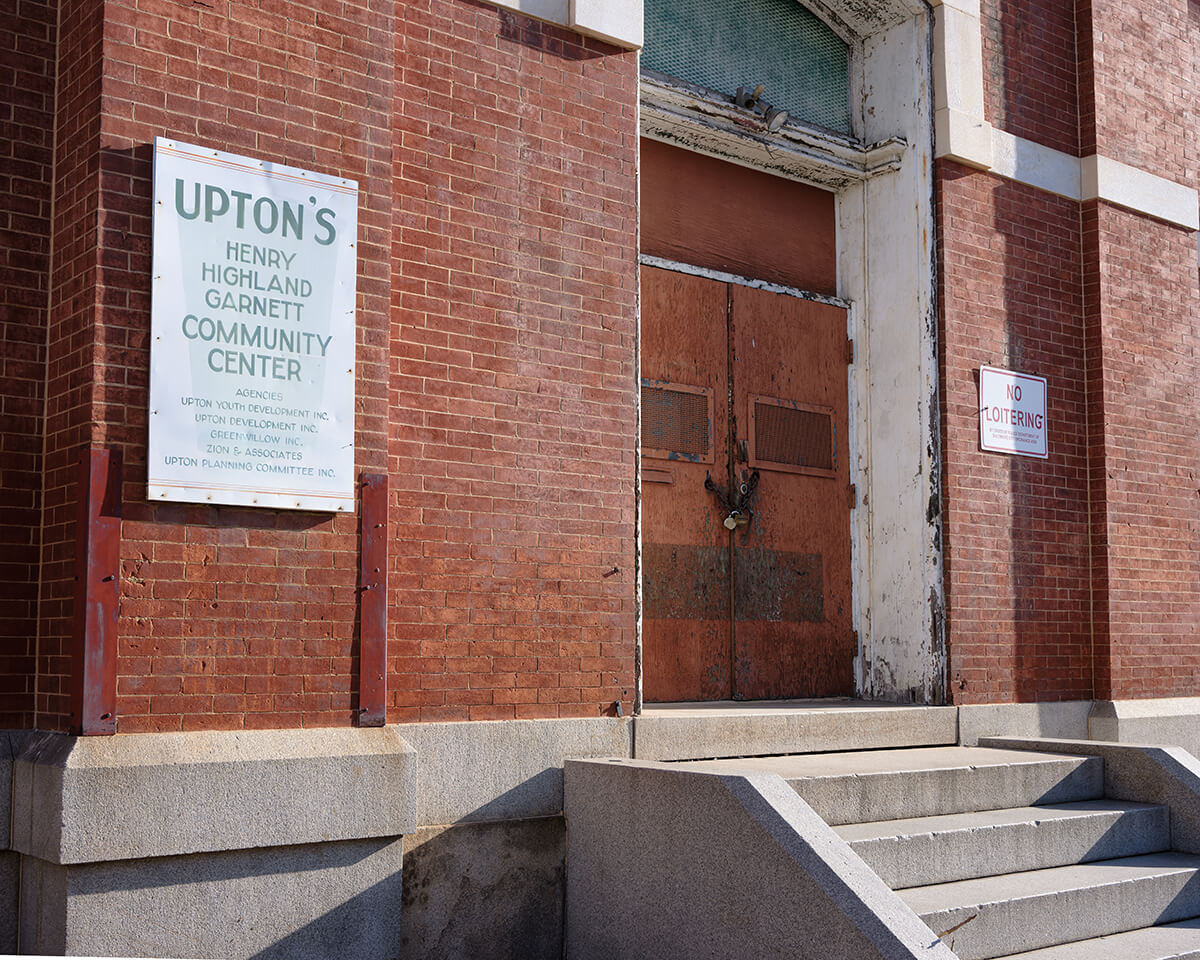

Nearly a half-century later, as he plans his retirement next month after a life of organizing and pastoring, Rev. Dr. Alvin C. Hathaway Sr. is now putting the finishing touches on an $8-million funding package for the preservation of the historic Henry Highland Garnet School. (A radical abolitionist, Garnet was born into slavery in Kent County, escaped, and later became the first Black preacher to give a sermon in the House of Representatives.)

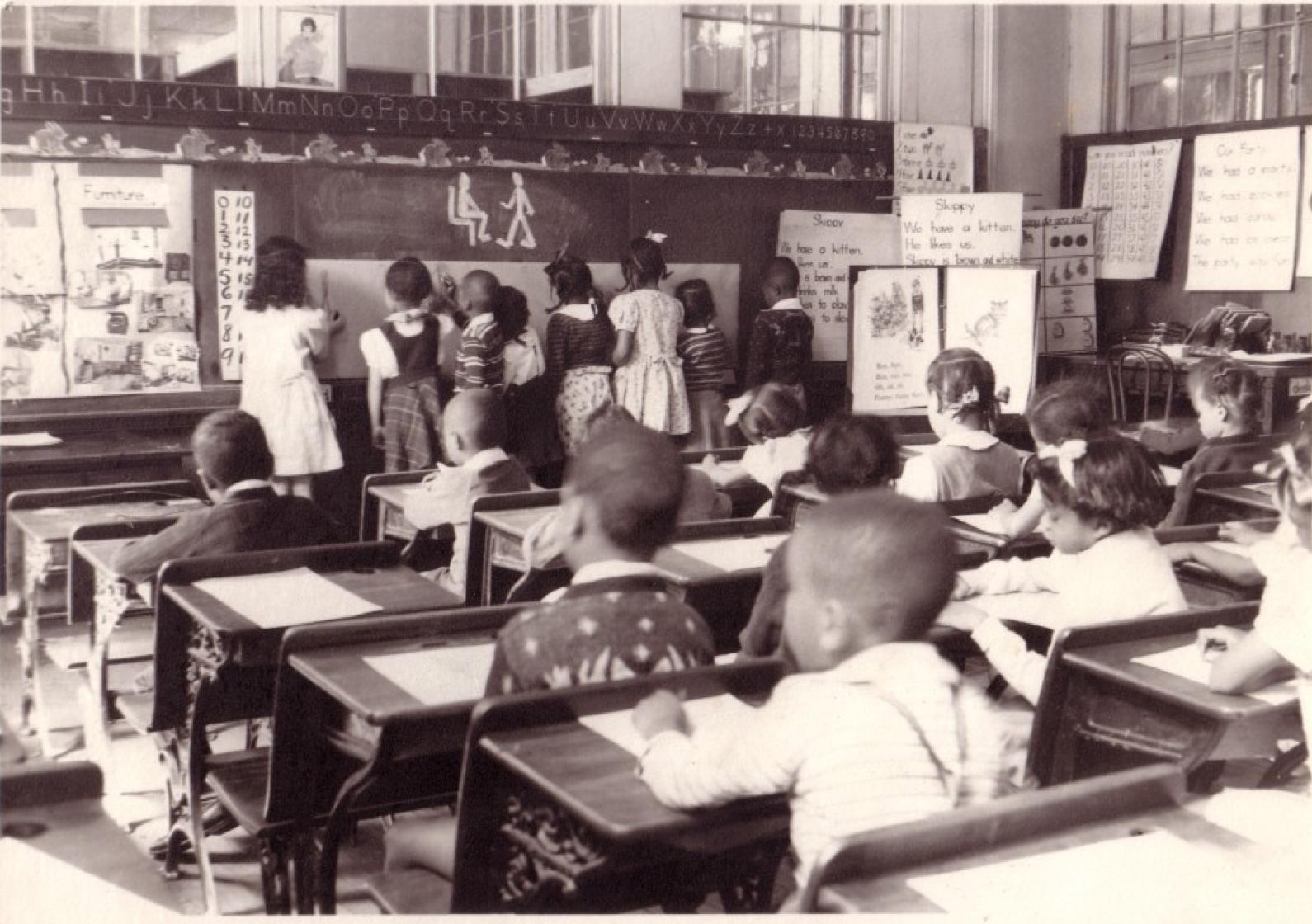

Located in Old West Baltimore, the 1877-built P.S. No. 103 was the segregated K-6 school attended by Thurgood Marshall, who grew up on the same street. Hathaway, whose religious calling came later in life—he earned his doctorate from Union Theological Seminary in 2006—also grew up here.

The landmark two-story building has been vacant since the ’90s, barely surviving a fire a few years ago. Hathaway hopes the transformation of P.S. 103 into the Justice Thurgood Marshall Center will mean even more to the surrounding Upton neighborhood than the saving of one of the city’s most historic schools. He envisions the project evolving into a community hub, linking to Union Baptist Church, where Hathaway serves, and sparking interest in preserving the former home and law offices of Juanita Jackson Mitchell, the first Black woman to practice law in Maryland, and Clarence Mitchell Jr., the NAACP’s chief lobbyist for 30 years.

By coincidence, as Hathaway opened the door to the building on a recent morning, a 1957 graduate of the school who was driving by stopped and offered to guide an impromtu tour. “My older brother and I went here,” said Randolph Long, walking up the steps with a smile. “The classrooms had interior glass windows and the principal’s office was just inside on the left. You couldn’t enter and miss it.”

Once the renovation is complete, the former school will host a University of Maryland-based center for education, justice, and ethics. While it will honor Marshall’s colossal contributions to the country, it will also pay homage to other trailblazers, including Walter Sondheim, the school board head who led the desegregation of city schools, and Hathaway’s former junior high and City College high school classmate, Elijah Cummings. Hathaway has been given all of Rep. Cummings’ campaign literature and plans to recreate his campaign office.

“Elijah was the smartest student in every class,” Hathaway says. “He was a nerd; we were focused on sports. One time in eighth grade, I got caught using a four-letter word and to avoid having my parents called, the teacher made me do a paper on its etymology. I asked Elijah for help. He did a great job of research and argued the word had Norwegian roots, was not profane at its origin, and I shouldn’t be found guilty at all. The teacher said we weren’t in Norway, but I still tell everyone I was Elijah’s first client.”