Thomas Broadus Jr. never knew his namesake father. He was two years old—the first-born twin of two sets of twins born to Thomas and Estelle Broadus—when his father, a U.S. Army private from Pittsburgh was shot in the back by a white Baltimore police officer in 1942.

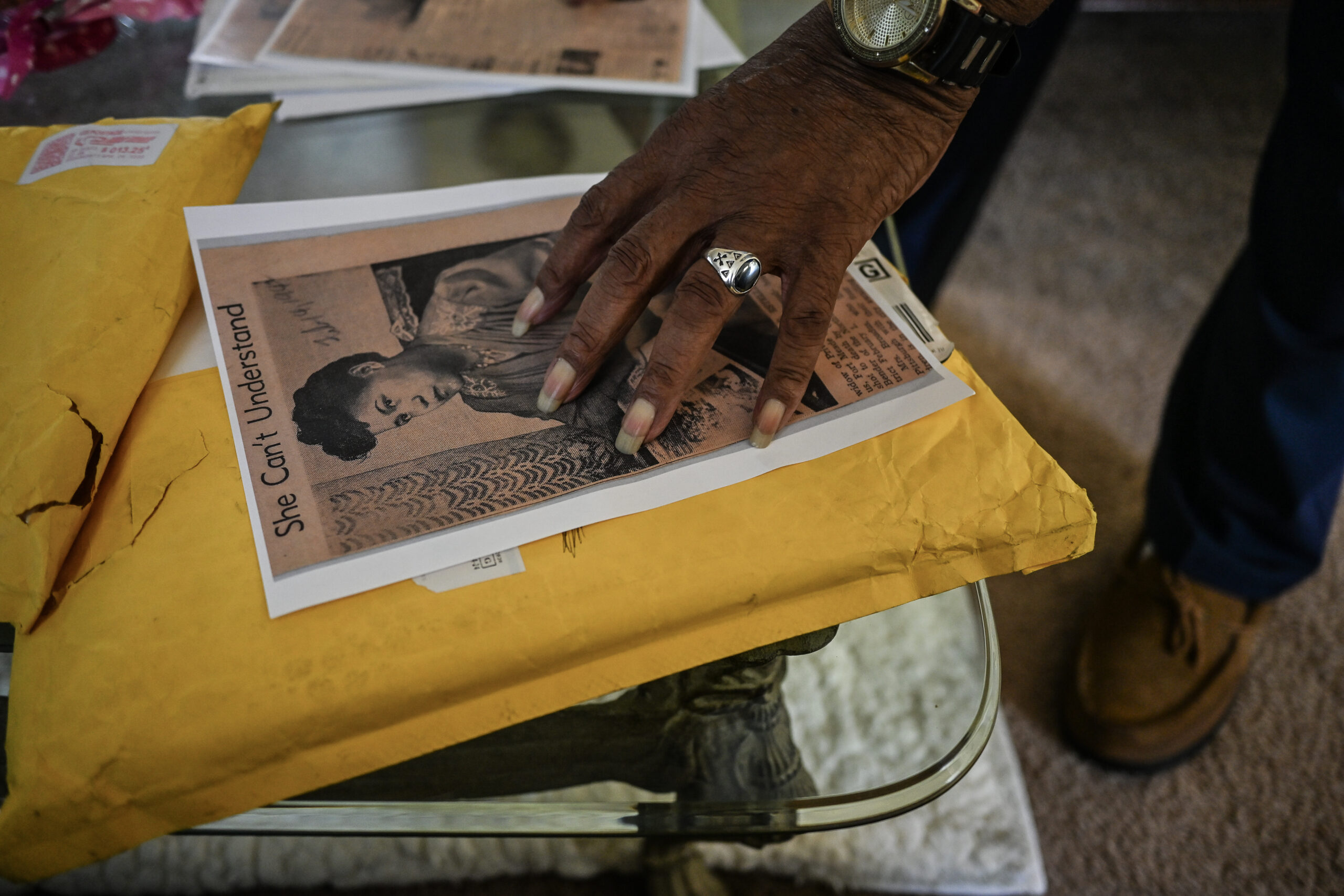

His mother, distraught by the slaying her entire life, never remarried. She rarely spoke of her husband, who had been stationed in a segregated unit at nearby Fort Meade, Maryland, when he was killed. She did not keep photographs of him in their home and never told her four children—even after they matured into adults—about the circumstances surrounding his wrongful death.

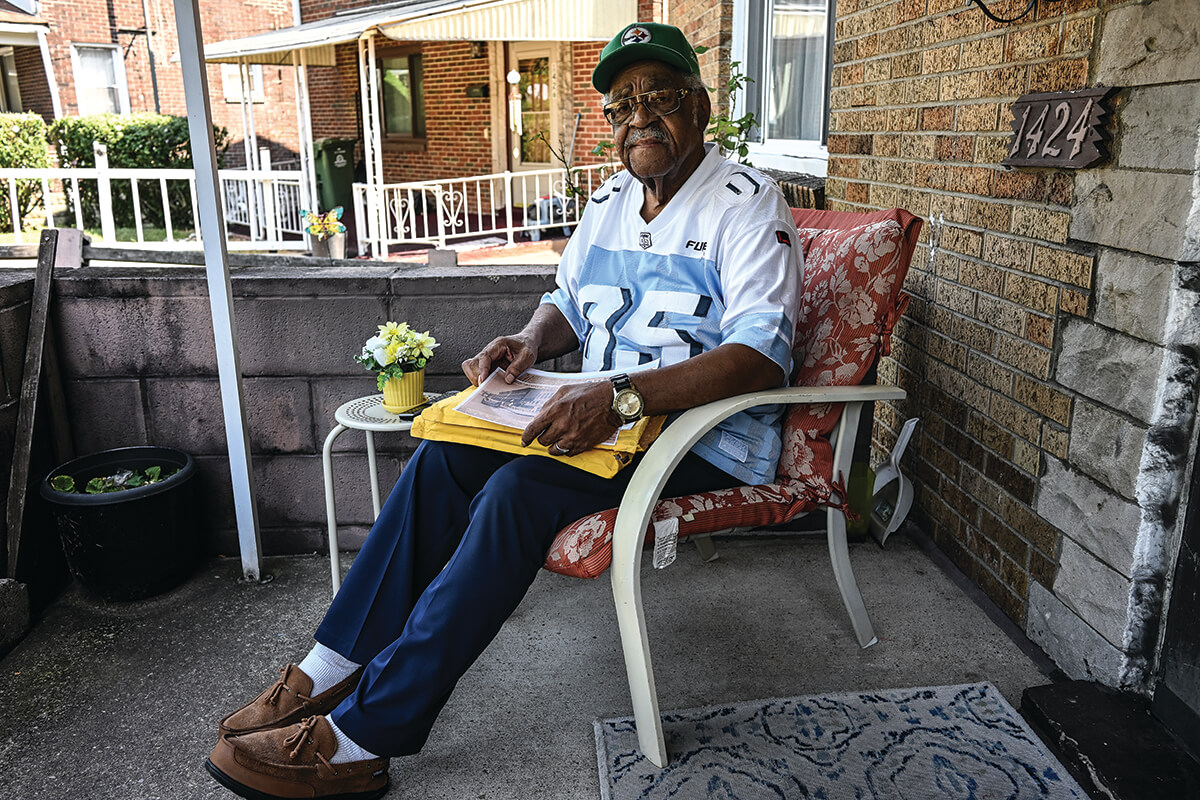

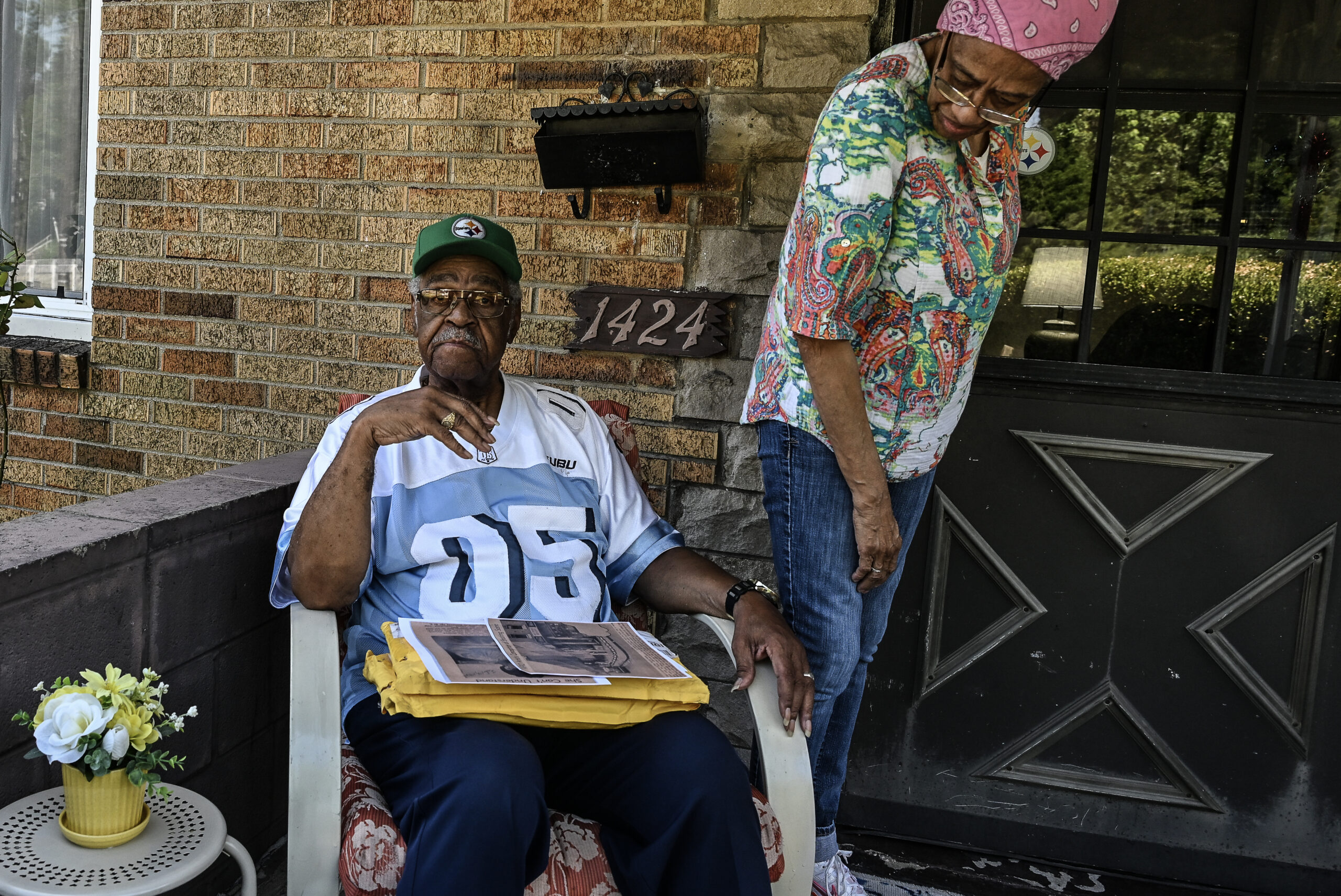

“You knew not to ask my mother questions about my father and, if you did, she would not answer them,” says the 85-year-old Broadus, who still lives in Pittsburgh and has one living sibling, a younger sister. “My grandad, who died when I was about 17, was real close to my dad. He didn’t talk about how he died, either.”

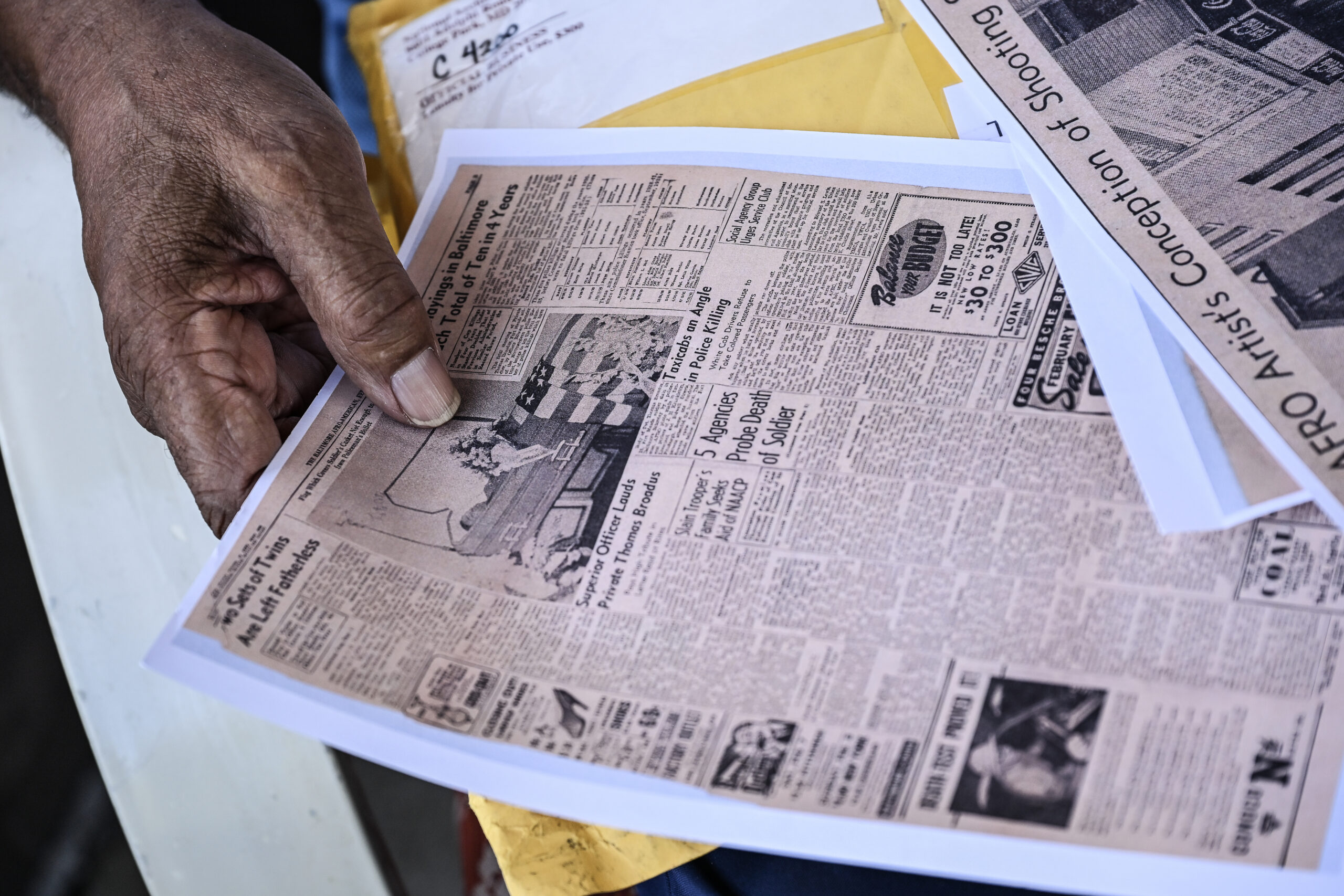

But three weeks ago, some 83 years after his father’s death, the retired Pittsburgh bus driver received a letter from the National Archives and Records Administration and a note from the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board of the United States government. They had recently voted to release more than 300 pages of federal investigative files related to the homicide, including documents from the Department of Justice, the Office of the U.S. Attorney General, the War Department, the U.S. Attorney for Maryland, and the Baltimore Police Department, including eyewitness statements, as well as real-time press clippings from The Afro-American and The Baltimore Sun.

Per standard practice, the Review Board mailed hard copies to Broadus before the file was made public—one of 15 such civil rights “cold cases” made public since this past December.

Established by Congress with the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act of 2018, but languishing for years for political reasons, the Review Board’s growing number of releases includes other Black servicemen, as well. As in the incident involving Thomas Broadus, Black soldiers from northern cities stationed in the American South during World War II all too often had to deal with hostile local law enforcement and a biased legal system.

After no one was held to account for the 1944 killing of a Black U.S. Army private from New York in Louisiana, Baltimore native Thurgood Marshall, then special counsel to the NAACP, told U.S. Attorney General Francis Biddle that attacks against Black servicemen were on the rise.

“These attacks are continuing to destroy the morale of our soldiers and sailors,” wrote Marshall, who would come close to his own lynching at the hands of a vigilante mob two years later in Columbia, Tennessee. At the time, in its response to inquiries from both Marshall and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who also pressed the U.S. Attorney General, the Department of Justice determined it could not pursue federal charges in the homicides of Black servicemembers—because there was no federal statute against killing service members.

Overall, there could be 5,000 to 10,000 investigative files from various unresolved civil rights-era cold cases. No one is certain. Not even the Review Board. The records that have been released—like the fatal police beating of a 46-year-old Alabama mother-of-eight in 1945, and the shootings of a New York Army private who, like Broadus, was unarmed—are, of course, painful for the surviving family members and their descendants to absorb.

“My father’s records, they are very thick files,” says Broadus, reached by phone recently at the home he shares with his wife, and just back from an errand with his great-granddaughter. “That cop shot him in the back as he was trying to run and get away from him. Then he kicked my father when he fell between the curb and a car.”

“And you know what I can’t understand?” he continues, his voice rising with emotion. “How can it be that my mom wasn’t never, never compensated for this? She had four kids with a man in the U.S. Army. She worked day and night to buy us food, to buy us clothes, to pay the rent all those years. I went to work when I was 14 or 15 years old to help out, but how much money can you make at that age? My mom did that, and she kept all this inside her all those years.”

Late Saturday night on Jan. 31, 1942, several cabs refused to pick up U.S. Army Pvt. Thomas Broadus and his companions, two fellow servicemen and two local women, along the West Baltimore entertainment district known as “The Avenue.”

Louis Armstrong was in town for the weekend, and it should have been a memorable night. After a couple of drinks at a club known as “The Spot,” the soldiers eventually hailed a lift from an unlicensed “jitney.” But before they could get in, a white police officer across the street intervened. He ordered them to wait for one of the city’s white-owned, Sun Company taxis.

The group walked away, but Broadus—described as neither drunk nor quarrelsome later by his fellow soldiers—lagged behind. He got into an argument with Ofc. Edward Bender, after Broadus, according to one of his fellow servicemen, said licensed taxi drivers “acted like they didn’t want to ride colored people.” Another witness overheard Broadus also tell the officer that he “wanted a colored cab and had a right to spend his money with whomever he chose.”

Accounts vary on how the physical altercation between the Army private and city cop began. Several witnesses reported Bender hit Broadus with his baton while Broadus still had his hands in his pockets. It was the last day of January. Others, including Bender, said Broadus seized hold of the officer first.

Though there is little dispute about what unfolded next.

A brawl ensued as the men took each other to the ground multiple times. According to a later military report, Broadus managed to “[get] possession of the policeman’s nightstick” during the struggle, landing blows about Bender’s head and arms before a crowd intervened and attempted to break up the fight. As Broadus pulled away and tried to flee, Bender grabbed his service revolver and fired, striking the 26-year-old in the back.

Witnesses said a wounded Broadus attempted to take cover beneath a parked car, but Bender approached and shot him again. When a bystander sought permission to take Broadus for medical attention, Bender arrested him for interfering. A Provident Hospital medical report backed up the witnesses who said Bender fired two rounds at Broadus. It found two gunshot wounds, both entering through Broadus’ back, with one bullet still lodged on the right side of his chest. He was formally pronounced dead at 1:30 a.m.

Twelve days afterward, the Baltimore City State’s Attorney filed an unlawful homicide charge against Bender, who had killed another unarmed Black man under questionable circumstances less than two years earlier. On February 25, a grand jury, which had heard several, but not all eyewitness statements, indicted Bender and referred the case to criminal court. Bail was set at $2,500 and he was released on his own recognizance.

However, without disclosing its reasons, the grand jury reversed its decision and rescinded the charges several days later. Bender, who had been treated for injuries at the city’s downtown, white-only Maryland General Hospital, was off the hook and reinstated. (Now known as the University of Maryland Medical Center, the hospital remained segregated until 1963, a year prior to the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibited race-based discrimination in public accommodations and federally funded programs.)

The shooting of the soldier galvanized the Black Baltimore community’s struggle around segregation and racial justice. Far from an isolated incident, Broadus’ death—in the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue on a Saturday night, one of the centers of Black culture in the U.S. at the time—marked the 10th killing of a Black citizen by white city officers over the preceding three years. The Afro newspaper described West Baltimore as “a tinderbox.”

That April, as the Maryland General Assembly wound down, NAACP chapter founder Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson and Afro publisher Carl Murphy organized a Citizen’s Committee for Justice protest, and more than 2,000 demonstrators marched in Annapolis in response to what was described as the city’s “wave of police brutality.” Some protesters said they had walked the entire 25 miles from Baltimore to the state capitol. Among other demands, protestors called for the dismissal of Police Commissioner Robert Stanton and the hiring of Black officers in the city. (The Broadus shooting took place mere blocks from where Freddie Gray was killed by police in 2015, and the center of that subsequent uprising some 70-plus years later.)

Governor Herbert O’Conor responded by establishing the “Commission to Study Problems Affecting the Negro Population.” In its report the following spring, the commission concluded Bender “was in no danger when he fired the fatal shot, for the soldier was then in full flight; and even if we accept the officer’s account of the episode, the soldier’s only offense was an assault upon an officer and for this grade of offense the killing of a fugitive to prevent his escape was not justified in law.”

The commission also wrote that the City State’s Attorney could not explain the rationale behind the grand jury’s sudden change of heart—nor why his office failed to bring the Broadus case to another grand jury.

Nonetheless, efforts to convince the City State’s Attorney to reopen the case were not successful. As revealed in a letter contained in the newly released files, the U.S. Department of Justice subsequently decided not to take up the case in 1943, stating that too much time had passed, and that pursuit of the case was unlikely to result in a successful prosecution. The U.S. Attorney for Maryland, in another letter contained in the files, said they concurred with the DOJ’s conclusion. In December 1943, less than two years after the shooting, the file was closed.

Bender, who was transferred to another beat, would eventually be promoted to sergeant.

The Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board work is currently mandated to sunset no later than January 2027, as set out in the original legislation. Given that its four board members were not nominated until 2021 and approved until 2022, recently, bills were introduced in Congress by Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-NJ) and Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) to extend that sunset date to 2031.

“Family members appreciate the public release of the records, which often provide answers to longstanding questions,” says Margaret Burnham, co-chair of the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Review Board and the founder of Northeastern University’s Civil Rights & Restorative Justice Project. “Many also ask, given the passage of time, what else might be done to acknowledge the harms they endured.”

As the Review Board has noted, six months before the United States joined the allies in World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt recognized that discrimination and segregation would hinder the coming war effort. Issued in June of 1941—just seven months before Broadus’ death—Executive Order 8802 banned federal government and defense industry discrimination “because of race, creed, color, or national origin.”

The order created an investigative agency to field complaints, commonly known as the Fair Employment Practices Committee. But, particularly in the South, historians generally regarded it as a toothless and ineffectual body. The order did little to protect Black enlisted men, who were typically relegated to segregated units, with limited opportunity for advancement. The National Archives states: “When assigned to bases in the South, these troops had to navigate segregation laws dictating their behavior off-base, as well.”

Northeastern’s Burnham, who is 80 and began her renowned civil rights career with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, points out that Broadus’ case is significant for several reasons—which is why the Review Board prioritized his files’ release.

“First, it’s a soldier, who is trying to make his way around town, off duty, but nevertheless battling the Jim Crow transportation system that African-American soldiers all over the country had to contend with,” she says. “This is not a bus or a train, but it reflects the same segregated transportation systems that we had in major cities, including Baltimore. While not a Deep South city, it is certainly still in the South, and for that reason I think it’s reflective of the challenges that soldiers faced navigating Jim Crow. Secondly, it’s particularly significant because it spurred a historic protest movement. That makes it clear that the killing of Broadus resonated with African Americans in Baltimore as a major civil rights issue.”

Burnham adds that many of the cold cases—not all involve homicides, some include assault, kidnapping, or other acts of violence—were not broadly known at the time by the American public. But there was often at least some coverage in the African-American newspapers of the period, she notes. Not only the Afro in Baltimore, which followed the Broadus case closely, but the Chicago Defender and Amsterdam News in New York, which also had national audiences informing the larger Black community.

“Even though in some of these Deep South cases, where there were no local reporters or local newspapers [covering a case],” she says, “the information about these cases would often get out through the national African-American newspapers.”

Following the Broadus shooting, for example, a Pittsburgh woman wrote to President Roosevelt—her thoughtful, handwritten letter is part of his War Department investigation file—highlighting the plight of Black servicemen. In addition to the Broadus case, she mentioned an incident earlier that month on Jan. 10, 1942, later referred to as the Lee Street Massacre, when at least 10, possibly up to 15, Black servicemen were killed by civilian and military law enforcement in Louisiana.

“Yes, our men are full of patriotism, American negroe [sic] soldiers, only to meet death because they are negroes before they reach the battlefields. And what do they get? Nothing,” wrote Estella Washington. “There are offices in the Army that the negroe can never hold. In defending America, if there is a hero his name is never called.”

She signed the last page, “A true and loyal American citizen,” and asked for a response.

The reply to her letter, as with most, was a perfunctory note that their concerns had been received. The War Department’s letter to Estella Washington, however, included a denial that any Black soldiers had been killed in the Louisiana event and an assurance that the officer who shot Broadus was being prosecuted by the civilian criminal court in Baltimore.

Eight decades later, the U.S. Army private’s son says that “it is never too late to do the right thing” and that getting some formal recognition and justice for his father’s wrongful death is “very important.”

“When I learned about all that happened to my dad, I thought about my mother, who was in her 20s,” Broadus says. “She didn’t know who to go to. She didn’t know what lawyer to contact, or anything like that.”

He adds that he would like someone, anyone, to contact him—a representative from the City of Baltimore, the Baltimore City Police Department, the United States Army. Or a lawyer.

“Somebody should call here and tell me something,” he says.

[Editor’s Note 9/2025: Since we originally ran this story in May, a local civil rights attorney has reached out to Mr. Broadus.]