History & Politics

The Hardscrabble Orioles Were the First Great Team in Modern Baseball

Many of the original O's are buried together at West Baltimore’s New Cathedral Cemetery.

“For the life of me, I could not run to get it,” future Hall of Famer John McGraw recalled of his first fielding chance as a minor leaguer. “It seemed like an age before I could get the ball in my hands and then, as I looked over to first, it seemed like the longest throw I ever had to make. The first baseman was the tallest in the league, but I threw the ball far over his head.” Errors ensued in seven of his next nine chances that afternoon.

Released six games after that debacle, the young McGraw could not face returning home to his Irish immigrant father, a railroad worker and Civil War veteran who’d told him to take up a regular job. Instead, the scrappy McGraw resolved to catch on with another club and make it as a professional ballplayer by any means necessary, which is exactly how he did it. The profane, pugnacious, undeterrable, break-all-the-rules third baseman—all of 5-feet-7 and 155 pounds—became the backbone of the first great team in modern baseball history, the equally uncompromising and hardscrabble 1890s Baltimore Orioles.

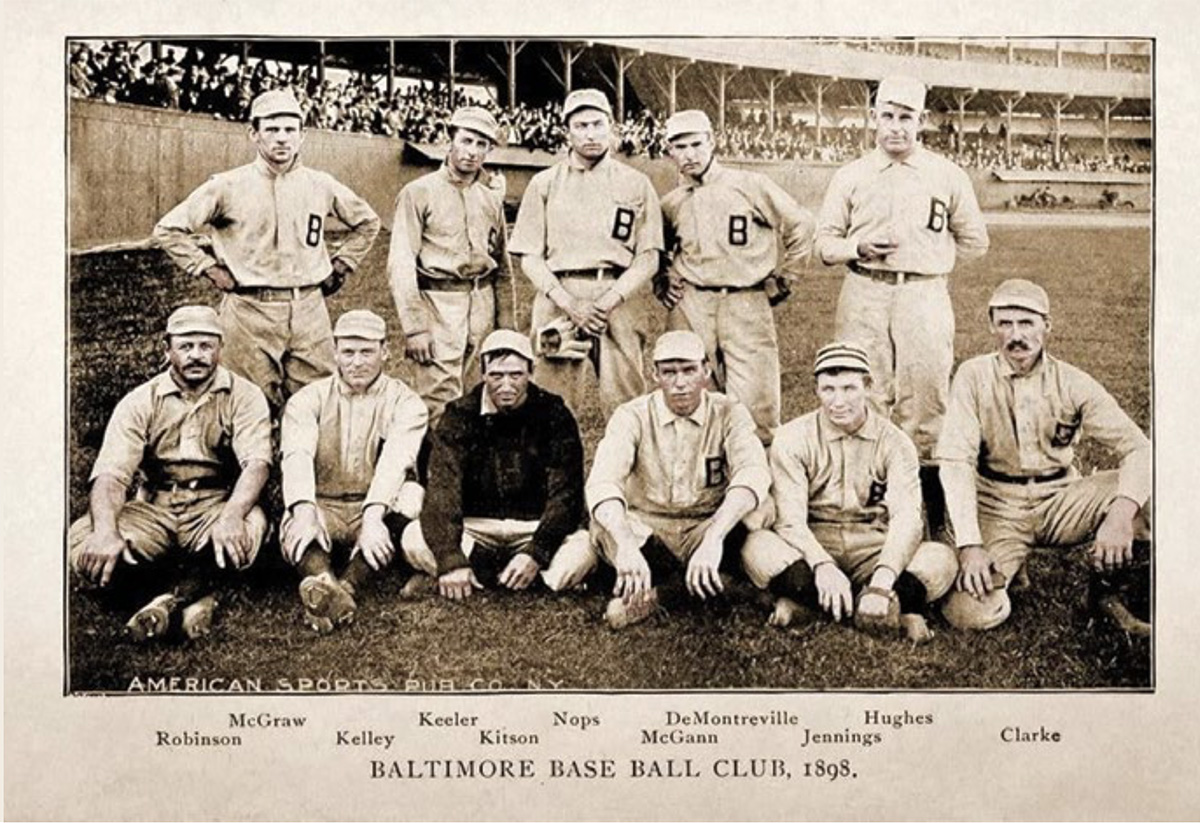

One of the most storied teams in the history of the game, the original O’s were a collection of motley characters, whose lineup reads more like a gang of Boston Irish mafia than a ball club, with “Dirty” Jack Doyle at first and the aforementioned “Mugsy” McGraw at third. “Boileryard” Clarke and Wilbert “Robbie” Robinson divvied up the catching duties. “Handsome” Joe Kelley, said to have kept a comb and small mirror in the back pocket of his uniform pants, and “Wee” Willie Keeler, the skilled batsman whose motto was “hit ’em where they ain’t,” manned the outfield. “Duke” Esper, “Kid” Gleason, “Doc” Pond, and “Sadie” McMahon, who actually did run with an Irish gang as a youth and was once tried for murder, worked on the mound, with the entire crew managed by “Foxy” Ned Hanlon.

These feisty O’s literally invented “small” ball—the sacrifice bunt, the hit-and-run, the double-steal, and the “Baltimore Chop,” the practice of bashing a pitch into the dirt in front of home plate so hard that it caroms too high for the fielder to throw out a quick runner sprinting toward first.

They threw body blocks on the base paths and slid into baseball lore with sharpened cleats while Ty Cobb was still a schoolboy. “We hear much of the glories and durability of the old Orioles, but the truth about this team seldom has been told,” 1890s umpire John Heydler recounted decades later in the 1950 book, The Baseball Story. “They were mean, vicious, ready at any time to maim a rival player or an umpire, if it helped their cause. The things they would say to an umpire were unbelievably vile, and they broke the spirits of some fine men. I feel the lot of the umpire never was worse than in the years when the Orioles were flying high.”

At least not until Earl Weaver came along.

Robinson, Kelley, Hanlon, and McGraw, who went on to a legendary managing career with the New York Giants, are all enshrined in Cooperstown. They are also buried together at West Baltimore’s New Cathedral Cemetery, which holds the distinction of being the final resting place of more Hall of Famers than any other funeral grounds, and has become something of a pilgrimage site for fans of old-time baseball. During their playing days, McGraw and Robinson put their earnings into a popular Howard Street saloon and pool hall, known as The Diamond, where, best as anyone can tell, they also invented duckpin bowling over cigars and beer.

McGraw, whose wife was from Baltimore, died from kidney failure two years after he retired from managing at 60. Robinson, meanwhile, had become manager and president of the minor-league Atlanta Crackers. Toward the end of the 1934 season, he slipped in his hotel room, breaking his arm and hitting his head on the bathtub.

Although he didn’t realize it, Robinson had also suffered a brain hemorrhage. He died a few days later, on August 8, 1934, with his wife at his bedside. It was less than six months after the death of McGraw. The two former teammates are buried not far from each other.

At the hotel, while being administered to after his fall, Robinson uttered his most enduring line. “Don’t worry about it, fellas,” he told those attending him. “I’m an old Oriole. I’m too tough to die.”