Sports

Rare Bird

After 50 years with the Orioles, Jim Palmer still isn't perfect. But give him time.

Outside the MASN television booth at Camden Yards, Jim Palmer is bouncing from side to side in the carpeted hallway, launching into baseball stories and bad jokes with practically everyone who walks by. One moment, he’s recalling when, as a 20-year-old phenom, he watched Moe Drabowsky strike out 11 in relief in Game 1 of the 1966 World Series. The next, he’s stopping former O’s shortstop and broadcasting colleague Mike Bordick to comment on their nearly matching blue suits. “Hey Mike, we look like we’re in a union.”

Feted this afternoon because this season marks 50 years since he broke in with the Orioles, Palmer is tossing out the first pitch before the home opener in an hour, and he’s either anxious or excited. Or he’s got ADHD. The man can’t stand still.

He chats up O’s executive vice president Dan Duquette and official scorer Jim Henneman, whose history with the club, Palmer gleefully notes, predates his own. When someone asks if he has been doing any throwing, he responds with a windmill circle of his right arm, a wisecrack about 50 Cent’s infamous ceremonial toss last year that nearly plunked a photographer, and an anecdote about Joe Namath, a Florida buddy. “Joe was throwing out the first pitch at a spring training game in Jupiter last year, and he asks for advice. I tell him, ‘Joe, whatever you do, don’t go onto the dirt [meaning the pitcher’s mound]’. Does he listen? It didn’t end well.”

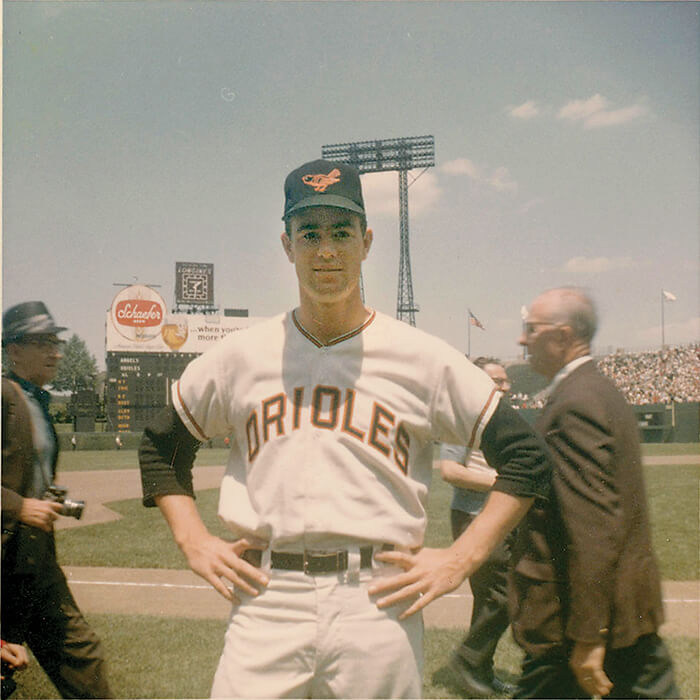

1965 rookie Jim Palmer the Orioles’ old flannel uniform and original cap. —Courtesy of Susan Palmer

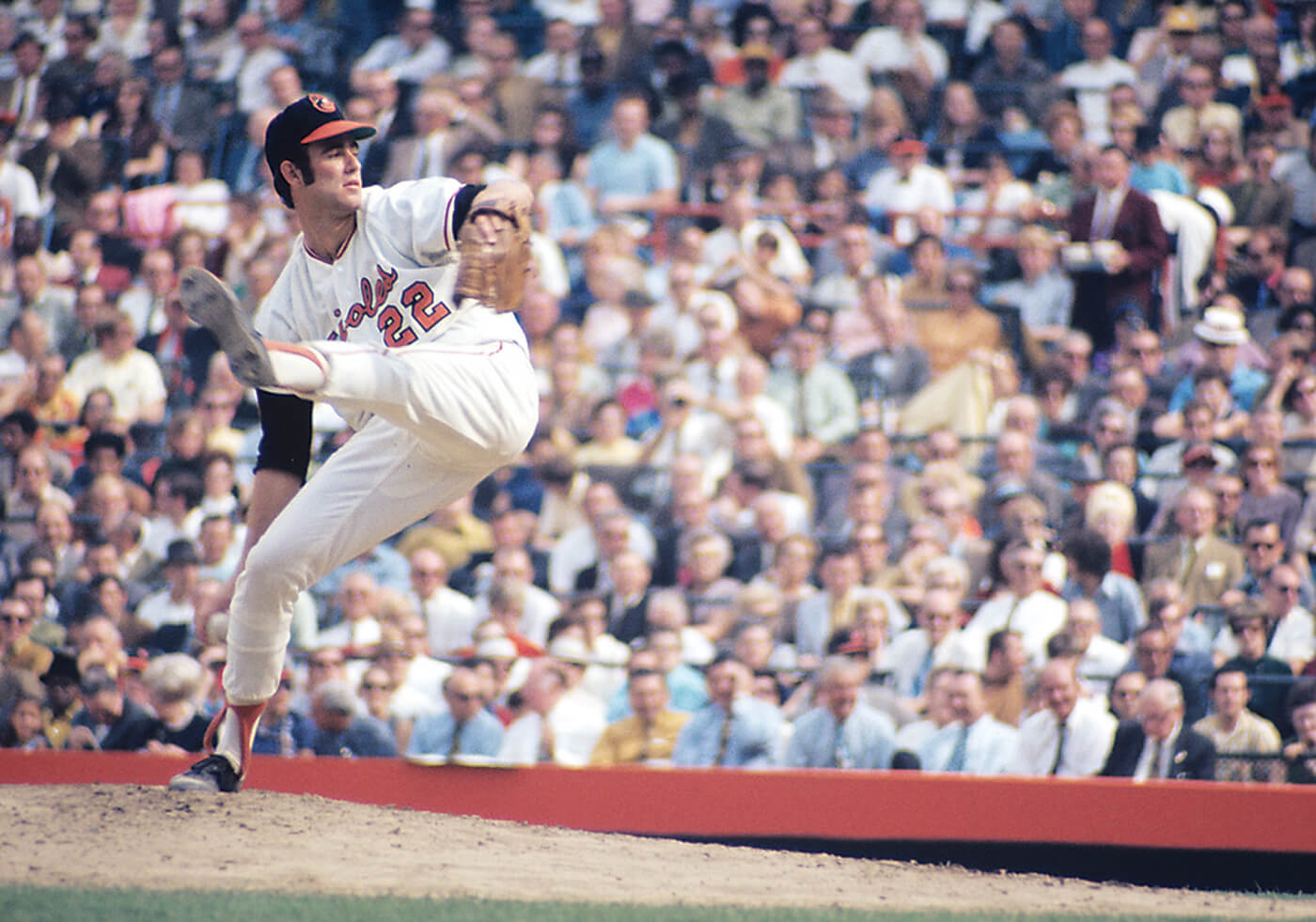

Later, he suggests to WJZ sports director Mark Viviano that he take the mound in his stead. “No one will notice,” Palmer says. It’s a funny nod to the fact that they occasionally get mistaken for each other, and then Palmer feigns his iconic high-kicking motion—the one bronzed in statue behind centerfield—raising his left foot to improbably graceful heights for someone who turns 70 this October.

It’s all constant motion and banter (it will be no surprise to O’s fans who is doing most of the talking) until Palmer takes the field. Making his way through the clubhouse, he trades jibes with longtime attendant Jim Tyler, fist bumps O’s centerfielder Adam Jones, and detours for a word with closer Zach Britton about anti-inflammatory medication. (“Purely preventive,” Palmer assures me, clocking my sudden concern for the young star’s health.) He ducks into Steve Pearce’s BP session and scoops a loose ball as former battery-mate Rick Dempsey searches for a mitt.

Finally, with a tug on the hand railing for leverage—the first evidence that the forever trim and well-coiffed Palmer isn’t completely dominating Father Time—he’s up the concrete steps behind home plate with announcer Jim Hunter introducing him to the sellout crowd.

“He won 268 games, the most ever by an Oriole . . . becoming the only pitcher to win a World Series game in three different decades.His number has been retired.

He’s in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown . . .”

Ignoring his own advice to Namath, Palmer climbs atop the hill and fires a strike on the corner because that’s how Jim Palmer rolls. It may be fine for every other creaky-kneed ex-jock or ex-President to take the easy way out and toss from the grass, but not Palmer, who is renowned as one of the game’s all-time great (and most exasperating) perfectionists.

“I thought Dempsey did a good job framing it,” O’s manager Buck Showalter chides him in the dugout afterward.

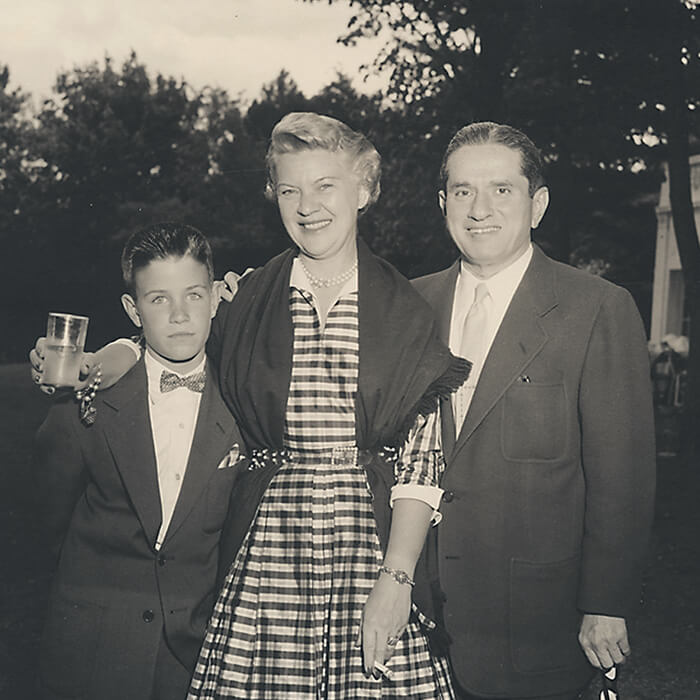

A dapper, 8-year-old Palmer with his parents. —Courtesy of Susan Palmer

The most revealing exchange on opening day, however, comes during the fourth inning, as Palmer’s anniversary cake is delivered to him in the broadcasting booth. Play-by-play man Gary Thorne asks him to reflect on his years with the organization and on the on-field ceremony, which included a $50,000 check from the team to Autism Speaks, a charity that Palmer has become involved with in recent years. Palmer’s 18-year-old stepson, Spencer, with whom he is very close, has been diagnosed with the condition. “I want to take a moment,” a clearly moved Palmer replies, collecting himself before thanking the Angelos family (who own the club) for their generous contribution and talk about his parents and the teammates who played behind him. What viewers didn’t catch—not because of anything Palmer did, but because the camera was tracking a Manny Machado fly ball to center—were his eyes welling up.

“He’s crying,” MASN’s stage manager whispers in the back of the booth.

Thirty-one years ago, at his press conference announcing that the Orioles had released him as a player, Palmer abruptly bolted from the room as his emotions rose—unable or unwilling to allow the public see him in a vulnerable light. If Palmer, who always appeared perhaps a little too poised over the years—never a hair out of place—is finally allowing us to see that life is, at times, overwhelming and emotional, well, that’s probably a good development. It doesn’t mean that he’s “average”—his biggest fear—just that he’s one of us.

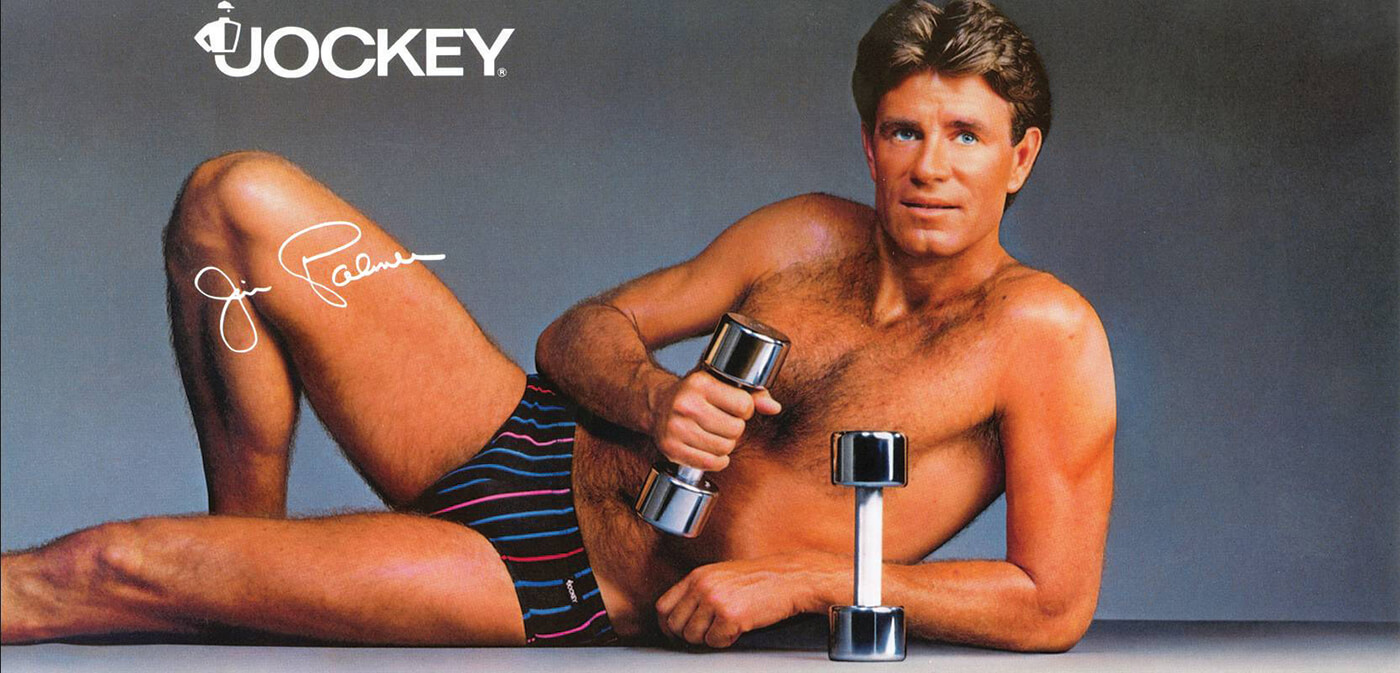

There are few, if any, public figures in Baltimore who have remained in the limelight like the Hall of Fame pitcher and former underwear superstar has for the past half-century. And like any professional athlete, entertainer, or politician, our perception of Palmer over the years is bound to reveal as much about ourselves as it does about him. He’s like a Rorschach test for longtime O’s fans. We can all agree that Palmer is one of the best pitchers ever—not only is he the only O’s player who was part of the team’s six pennant-winning and three World Series-winning squads, but he did it across three decades. But how else do you perceive him? Is your central image of him as a ballplayer in his 1970s prime? As Jockey’s blue-eyed poster hunk in the ’80s? Or is it as the broadcaster he’s become over the last 30-plus years? Is your impression that he’s arrogant? Self-absorbed? Or a class act who gives back to the community?

Palmer In his heyday as the face and body of Jockey underwear.

The answer, at least partly, depends on your age and your gender. Every female co-worker I spoke to about this piece told me: “We have to get one of his Jockey pictures included in the art.” Not one guy mentioned his underwear ads—in which he famously posed, tanned, smoldering, and hairy-chested, as was the fashion in those days, in only his briefs. It also matters whether you’re a casual baseball observer, who maybe thinks Palmer expounds too much on the air, or an inside baseball fan, who thrives on strategy, minutiae, and O’s history. And it makes a difference whether or not you lived in Baltimore when he pitched here, and thus witnessed his epic 14-year battle with Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver, his cockiness on the mound, his demands for more money, and his outspokenness off the field. In that case, maybe you still see him as another entitled ex-jock.

This description of Palmer as dichotomous and polarizing isn’t hyperbole. Once, during a Palmer salary dispute in the mid-’70s, this magazine ran a poll asking readers which player they most wanted their sons to grow up to be like. Brooks Robinson won hands down. The player readers least wanted their sons to grow up to be like? You guessed it.

For his part, Palmer says he has few regrets from his playing days, except that he wishes he occasionally had been “more tactful” in his dealings with Weaver. “Otherwise,” he says, “I’d probably do everything the same.”

Which is not to say that Palmer was ever a bad person. He donated the profits from the Jockey posters to the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. He has always given a tremendous amount of time to charity, been generous with fans—he joined Twitter this winter and responds to tweets—and remained loyal to his teammates and friends. Former O’s first baseman Boog Powell, the guy with the barbecue stand on Eutaw Street, will tell you Palmer was the one of the first people to visit him in the hospital when he had colon cancer. Hell, when Palmer and his first wife separated (they married at 18), Palmer bought a house down the street so he wouldn’t miss time with his two daughters. How many people do that?

Baseball writer Thomas Boswell got into all this in a lengthy piece for Playboy way back in 1983, Palmer’s last full season. Palmer was 37 by then, and Boswell, who had been covering him for years for The Washington Post, still hadn’t gotten a handle on his contradictions. The story was titled, “Will the Real Jim Palmer Please Stand Up.”

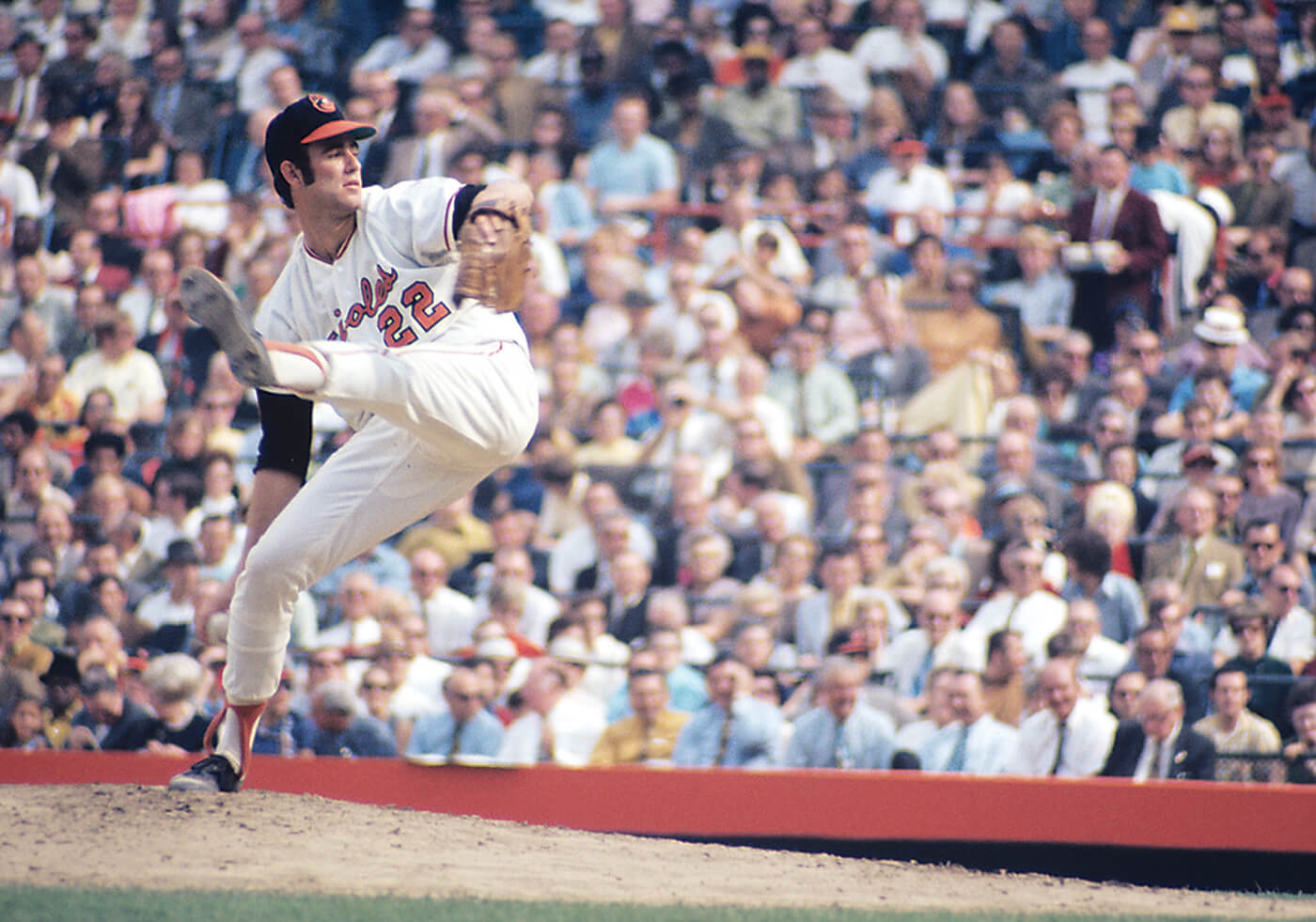

On the hill. —Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles

In those days, Palmer had a earned a label as a hypochondriac—which didn’t fly in blue-collar Memorial Stadium—a charge he’ll admit to today with self-deprecating humor. Weaver famously once said, referring to Palmer’s ailments, that “the Chinese tell time by The Year of the Dragon or The Year of the Horse. I tell time by The Year of the Back, The Year of the Elbow. This year, it’s The Year of the Ulnar Nerve.” But Palmer also regularly logged 300 innings per season, unheard of today. He also had a reputation for arrogance: Palmer was known to show up teammates, occasionally throwing his hands in the air when they booted a ball. He criticized other players, Weaver, and the front office in the press. He showed up Weaver, too, by moving the defense around in the outfield from the mound with big waves of his arms. (“I’d wave right back and then, when he turned around, I’d move where he wanted me,” former O’s outfielder Ken Singleton, recalls with a laugh. “He was usually right.” Singleton’s sentiments are echoed by other former Orioles.) And he was even booed on 33rd Street, especially as inevitable physical decline hurt his performance, and arm injuries—real or imagined—led him to pull himself out of the lineup.

To fans, male fans at least, now in their 50s, who grew up watching him in action, the 6-foot-3, Prince Valiant-handsome hard-thrower often came off as a cocky prima donna. But he was also “our prima donna,” as an older buddy recently put it to me. “We liked Palmer. Our fathers liked [the more stoic] Dave McNally.”

A quote often attributed to Palmer—“The only thing Earl knows about pitching was that he couldn’t hit it”—was actually said by McNally first. Palmer himself makes this clear. He just repeated it so often that people came to believe it was his.

“Oh, he was definitely a diva,” says longtime Baltimore sports aficionado and author Dean Smith, who wrote a well-received book about the Ravens’ last run to the Super Bowl. “But I also remember when I was a kid, and all through my parents’ divorce when baseball was kind of the thing I clung to, and there wasn’t a lot I could count on maybe, that he was the guy you could count on to win when the Orioles needed a win.”

Then Smith mentions one more thing about Palmer that happened three and a half years ago. It was, perhaps, the first time his public mask really came off, and it endeared him more to fans than anything he ever did as a player.

During an O’s-Twins telecast from Minneapolis, news filtered through Baltimore, eventually reaching Palmer in the booth, that his close friend Mike Flanagan, a protégée who’d won a Cy Young award in 1979 and remained with the club, as a pitching coach, broadcaster, and then executive, had committed suicide. The breaking story was crushing for the city and, of course, for those in the O’s organization, but Palmer managed to hold it together and get through the game. Immediately afterward, however, in the post-game wrap-up, the Flanagan tragedy was addressed by MASN’s in-studio hosts, and when asked to comment, the guy with the rep for coolness just broke down and sobbed.

“It was,” Smith says, “the most human moment I ever saw watching sports on television.”

Dempsey, his former teammate and current broadcasting colleague, says he has seen a change in recent years.

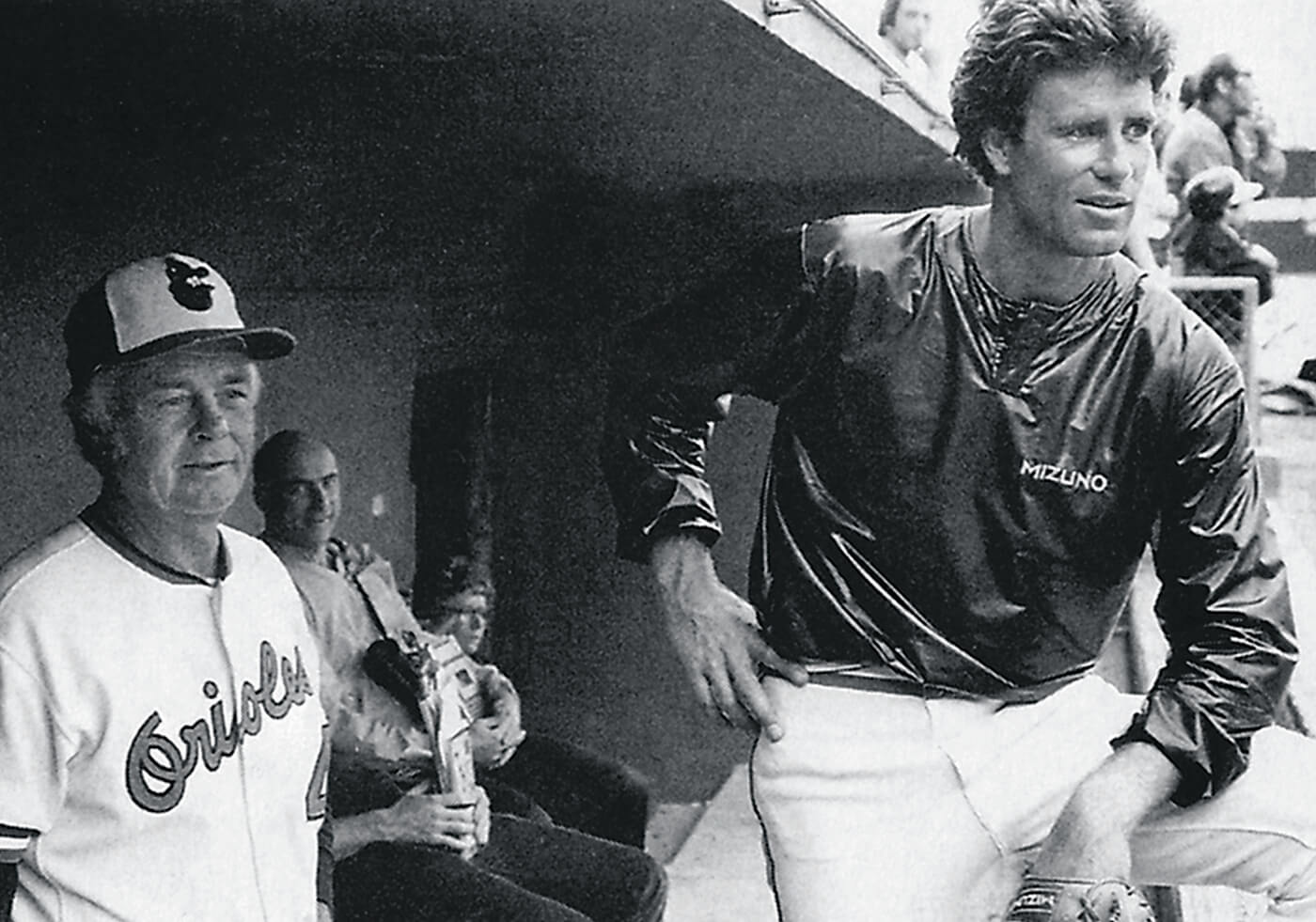

Next to Earl Weaver. —Courtesy of Joni Palmer

“You know, he was in the stratosphere when I arrived,” Dempsey says, referring to the 1976 blockbuster O’s-Yankees trade that brought him to Baltimore. “He was at a level in baseball, and then a place with the TV commercials, Jockey, and everything else, that few people can fathom. I can see that maybe people would view him as too big for his britches or aloof, although he wasn’t that way to the people who knew him. But the last few years, though, especially because of his stepson and some of the other things that have happened—you start losing some of your teammates and people close to you—I think he’s more focused on the relationships in his life.”

It’s safe to say that no Orioles player again will ever be such a lightning rod on the field and off it. But as we celebrate his golden anniversary with the team, it’s important to remember that he’s a living legend whose accomplishments on the mound will never be matched.

“Look, if I live to be 120, it won’t be long enough to see another pitcher do what he did,” former O’s catcher Andy Etchebarren says bluntly. “We had four 20-game winners—Palmer, [Mike] Cuellar, [Pat] Dobson, and McNally—in a four-man rotation. You’re never going to see that again, either. McNally won 20 games, what, four times? Well, Palmer won 20 eight times. Eight times in nine years. You should check this, but I think his best year he completed 25 games with 10 shutouts. [Ed. note: He did.] Who is ever going to do that again?”

And, as Etchebarren explains, it is not just because of Palmer’s singular ability that no one will ever accomplish the things he did. The game has obviously changed. In a world of expanded five-man rotations, pitch counts, and specialized bullpens, going a mere six-innings—anathema for Palmer and the Seavers and Gibsons of his era—is now considered a “quality start.” Still, it’s not like anyone matched what he did when they had the chance. Palmer won more games in the 1970s than anyone else in baseball.

There’s another reason Palmer’s golden anniversary is so significant: He’s still with us, every week for six months a year, covering the resurgent—and thank goodness for that after 14 losing years in a row—franchise. He doesn’t make every road trip, but Palmer is also on social media on a daily basis; he has nearly 10,000 Twitter followers, and more by the day. He even started his first Twitter storm in April after he called out the Red Sox’s David Ortiz for complaining about an ump’s decision and getting ejected in the middle of a tight game.

It’s ironic, too, that Palmer—nicknamed “Brash” as a rookie before teammates noticed his fondness for pancakes on pitching days and stuck him with “Cakes”—has become the old-school dude calling out players like Big Papi for not playing the game “the right way” or yapping out of turn. (During the kerfuffle, Jim Rice, the great Boston slugger and Palmer contemporary, noted, “Who cried more than Jim Palmer?”)

It’s also easy to get the impression that Palmer was always destined for greatness. An all-state performer in three sports, including a scholarship offer from John Wooden to play basketball at UCLA, he was a bonus baby signed after high school who seemed headed straight for stardom. And at first, the script stuck.

In Game 2 of the aforementioned 1966 World Series—after watching Drabowsky mow down the likes of Maury Wills, Willie Davis, and Wes Parker—the 20-year-old Palmer, who’d gone 15-10 that year, shut-out the heavily favored Dodgers on four hits at Chavez Ravine. That game appeared to be something of a passing of the torch, as it was the 30-year-old Sandy Koufax’s last start ever while showcasing Palmer, the phenom, to the baseball world. It even turned out, at least according to the story Palmer got, that Frank Sinatra and his Rat Pack buddies had taken the 40-1 Las Vegas odds on an O’s sweep. The next year at spring training, his performance earned him and several teammates a front row table—per Sinatra’s invite—at one of Frank’s shows at Miami Beach’s famed Fontainebleau hotel nightclub. “I could’ve reached out and grabbed his leg,” Palmer says. “And we met Mia Farrow.”

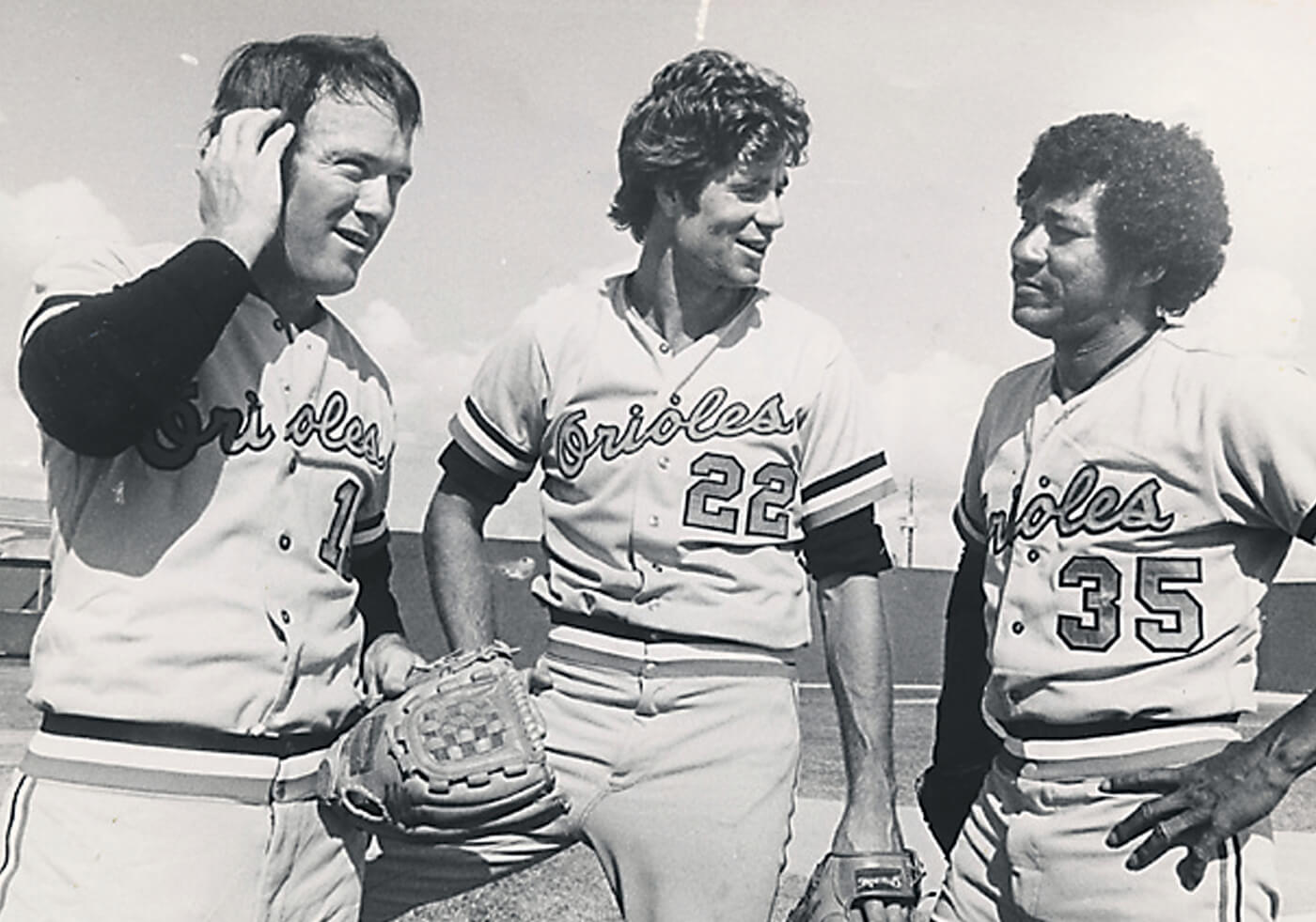

With Dave McNally, left, and Mike Cuellar, right. —Courtesy of Susan Palmer

Palmer didn’t know it at the time, but catching Sinatra’s act and meeting Mia Farrow would be the highlight of the season. He pitched nine games in 1967 before a bicep injury forced him to sit down. That issue later developed into a rotator-cuff injury, which is usually fatal to pitching careers. Remember once-promising O’s pitchers Wayne Garland and Ben McDonald?

Forced to the minors and the Puerto Rican winter league for nearly two full seasons, Palmer strongly considered retiring and going to college, even taking classes at then-Towson State. But with his fastball gone—it eventually returned after a long rehab and the right anti-inflammatory (reecall the conversation with Britton?)—he struggled, but he also fought. He worked on his curveball and change-up, and learned how to pitch, not just throw.

Like Koufax, who also was erratic as a young pitcher, and other power pitchers—Nolan Ryan comes to mind—it took Palmer a while to harness that rocket right arm.

Etchebarren, who first caught Palmer as a teenager, says Palmer threw into the upper 90s, “between 95 and 100 miles per hour,” when he came up. And not a stadium scoreboard 97 or 98, numbers which Etchebarren believes are inflated today. “He had a fastball that exploded. Batters couldn’t catch up to it,” Etchebarren says. “It looked like it was coming belt high, and it’d be up at their chest.” But Palmer also had no idea where the ball was going back then. “He’d strike out 10 and walk 10. There was no one who wanted to warm him up in the bullpen,” Etchebarren adds with a laugh. “Charley Lau [the Orioles back-up catcher, who later became a prominent hitting coach] would refuse to put on the gear.”

Boog Powell had already established himself when Palmer arrived at spring training as a rookie. He says the veterans were all impressed by how hard Palmer threw in his first spring training, but also knew the real test would come when the team went north. He remembers one early game when Palmer threw a high fastball to the White Sox’s Moose Skowron, who lined it out of the park. “I was in left field thinking, ‘Welcome to the big leagues. You can’t throw that pitch to everyone.’ But he adapted.”

Finally healthy in 1969, and now a more complete pitcher, Palmer threw a no-hitter and helped lead the O’s back to the World Series. Over the next decade, he proved himself the American League’s best starting pitcher, finishing in the top five in ERA every season, except for an injury-plagued 1974.

“If I had one game to win—and I’m talking about being able to take anybody—I’m taking Jimmy,” says Powell.

“When I came over [from the Yankees], he was in his prime and knew what he was doing,” Dempsey says. “He told me right off, that if he got behind in the count, to go and sit a half-inch off the plate, and call for a fastball down and away. He was so good by then, I could’ve caught those pitches with my eyes closed.”

Of course, if there will never be another pitcher like Palmer, there will also never be another manager like his nemesis, Earl Weaver. The volatile, chain-smoking Earl of Baltimore got tossed from a record 91 games, and remains the only manager who got thrown out of both ends of a doubleheader—two times. He was the opposite of Palmer in every way—except desire to win—and the stories of their dysfunctional relationship would strain credulity if Palmer himself hadn’t written an entire book about it, Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine. One memorable anecdote that didn’t make the book involves Palmer getting struck so hard on the knee by a line drive off the bat of Kansas City’s Ed Kirkpatrick that the ball ricocheted into the O’s dugout. Weaver had signaled for a slider on the pitch, which Palmer didn’t want to throw, but had relented after a meeting with Etchebarren on the mound. As he limped off the field, with the trainer checking on him, Palmer and Weaver went after each other, arguing who was at fault—Weaver for calling the wrong pitch or Palmer for throwing to the wrong location.

However, if there was ever any doubt about Weaver’s loyalty to the guys who played for him, particularly Palmer, consider the story of the 1993 old-timer’s game, played before the All-Star Game at Camden Yards. Managing the American League squad, Weaver had penciled in former Orioles all around the diamond, including Palmer on the mound over Bob Feller, the Cleveland Indian great. When word got to Weaver that Feller, one of the few pitchers ever to receive a higher percentage of Hall of the Fame votes than Palmer—and a World War II hero to boot—wouldn’t pitch at all unless he started, Earl’s response was, “F*ck him. He never won any games for me,” Palmer says with a laugh.

Palmer tried to convince Weaver to start Feller. “Which Earl finally agrees to do,” Palmer continues. “And then, after the first guy up hits a ball past Boog at first, which he probably should’ve had, Earl goes out and yanks Feller and waves me in.”

It’s interesting, too, that of all the former players who eulogized Earl Weaver at his funeral two years ago, it was Palmer who was the most outwardly emotional. “Earl and I had a love-hate relationship,” Palmer says. “It seemed like I was never good enough for Earl. But he did make me better.”

Palmer didn’t express much concern when Weaver retired in 1982, but he remains convinced that he would’ve gotten the chance to work through his slow start in 1984—which prompted the Orioles to release him after he refused to retire—if Weaver had still been around. Instead, the Birds and new manager Joe Altobelli decided to make room for younger players, at least in part, Palmer believes, because the Detroit Tigers were running from the rest of the American League with a 35-5 start. “I think with Earl, I would’ve been given the opportunity to find out if there was anything left in the tank, which is all you can ask for.” Although Palmer leaves it unsaid, he desperately wanted, of course, to continue his chase toward 300 wins—the mountaintop for starting pitchers.

Seven years later, he would even make an aborted comeback at 45 to see if any life had returned to his arm. (It hadn’t.)

If Game 1 of the ’66 Series remains his fondest Orioles memory, the drive to Memorial Stadium following his release had to be his worst until Flanagan’s death. “Driving down Walther Boulevard, you’re thinking about everything from you’ll never play in an Orioles uniform again, to when your mom drove you to Little League games in the back of the station wagon.”

In front of a MASN camera while coverIng the Orioles. —Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles

It’s also worth noting as Palmer reflects on his playing career—from his youth in California to the end as a Hall of Fame-worthy big leaguer—that although things may have looked shiny and polished on the outside, life was not simple growing up. Palmer, as many know, was adopted. Then, at nine, his adoptive father died suddenly. Later, his mother moved from New York, where he’d been born, to the West Coast, remarrying a man named Max Palmer, who became his second father figure. Max lived long enough to attend his Hall of Fame induction and Palmer adored both men.

As far as his post-baseball career, Palmer was fortunate that he already had a second-career—as a model, commercial spokesperson, and broadcaster with ABC Sports.

Always a solid color analyst, he has found his groove in recent years alongside Thorne. In one poll last year of baseball fans, they were named the third best broadcasting duo in all of baseball. The joy of listening to Palmer today is partly attributable to a soft voice that’s easy on the ears. But his baseball savvy, remarkable memory, and half-century of experience also allows him to create the sense that you’re inside the game as it unfolds. To this day, he remains an incredibly hardworking student of the game—up at 4:15 a.m. to drive from his home in Palm Beach, FL, to Sarasota for spring training games, for example, so that he can watch and meet with Orioles and the opposing team’s players and manager.

During the season, he’s awake around dawn after night games, and then off to the gym and to run errands before exchanging e-mails and thoughts on that day’s lead-in with MASN producers. He’s at the ballpark three hours before each game, hanging out with the O’s staff, scouts, and players, as well as the visiting club’s manager and coaches, many of whom he’s known for years.

“I’ll usually try to take an afternoon nap,” Palmer says, referring to his game-day ritual, “but that night’s game is going around in my head, and it never works.”

I reached out to Palmer’s wife, Susan—it’s his third marriage—inquiring about her husband’s detail-oriented proclivities and tendency, well, to stay on the move.

“Oh, you’ve got to understand, he gardens, does the landscaping—he loves it—he cooks, he cleans the house,” says Susan, a sharp and energetic go-getter herself, who runs a home décor shop in Palm Beach. “If the driveway or something needs power washing, he’s going to do it. If he’d made $30 million like the players today, it wouldn’t matter. He’d still do it all himself. One, because everything has to be done just right, and two, because he can’t stand not to be doing anything.”

Time may be softening Jim Palmer, taking the edge off some of the contradictions, but he is who he is.

“We do have an occasional slow Sunday, when nothing is happening,” Susan says, “and we will just hang out and watch some sports on television together. He’ll fall asleep at some point, naturally. And then, he’ll shoot straight up.

“‘What am I doing?’” he’ll say. “‘I’m wasting my life.’” And then he’s right out the door, on to the next thing that’s got to get done.”

Editor’s Note: This story is from the collection, If You Love Baltimore, It Will Love You Back: 171 Short But True Stories from Senior Editor Ron Cassie, due out Oct. 1 from Apprentice House Press at Loyola University Maryland To support local stores, it can be also pre-ordered through bookshop.org.